The odds are long, but the payoff is big. Only about one in three companies successfully evolves in the face of industry disruption. Trillions of dollars of shareholder value have vaporized as once high-flying companies failed to navigate major shifts driven by technology, consumers, or regulation. But companies that do make the transition often create even more value than they had previously.

The 2017 Value Creators

- Disruption and Reinvention in Value Creation: The 2017 Value Creators Report

- Value Creation and Corporate Reinvention

- Creating Value from Disruption (While Others Disappear)

- How Top Value Creators Outpace the Market—for Decades

- The 2017 Value Creators Rankings

Disruption, including rapid technological change, is at the top of most companies’ agendas, and rightly so: more industries and companies than ever before are facing the need to adapt. As Cisco’s John Chambers told the Wall Street Journal in 2015, “Every company’s future is going to depend on whether they catch the market transitions right.” Here’s what successful companies did to catch those transitions right.

Long Odds…

The track record is stark. Across a long list of industries (including agriculture, apparel, financial services, food, media, pharmaceuticals, retail, technology, and travel), substantive industry shocks have hobbled, if not crippled, incumbents. For the relatively few that navigated the transition, five numbers stand out:

- 33: The percentage of companies that successfully steered through the change when industry disruption occurred. The other 67% went out of business, got bought, or stumbled through years of stagnating or declining value.

- 10: The percentage of market capitalization that constituted a sufficiently large bet. Companies need to bet big to overcome the drag of the old way of doing things and reach the critical mass that will enable the business to flourish in the new regime. Those that do not make bets of this magnitude or more are likely to fail.

Companies need to bet big to overcome the drag of the old way of doing things.

- 20: The rough percentage (generally from 10% to 20%) of revenue that had to be generated by the new business model to overcome internal resistance and signal to investors that the change was significant and successful. Internal organizations will conspire against half-hearted transitions, and investors are unlikely to recognize or reward companies that do not identify a credible path to move a fifth of their business or more into the new paradigm.

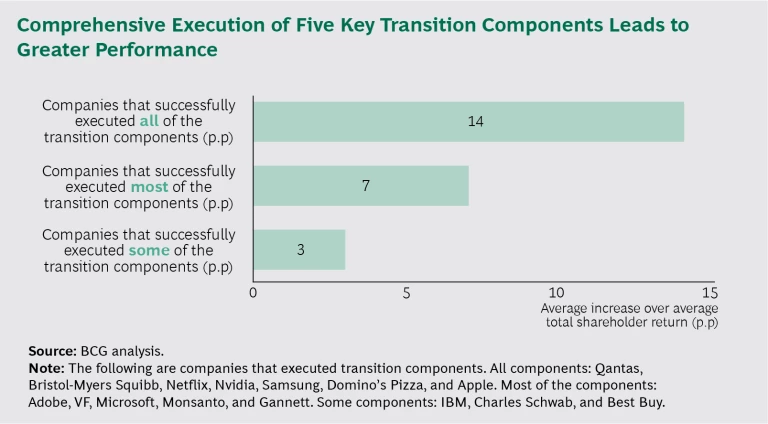

- 5: There were five components to a successful response. The key for successful companies was that they almost always employed a coordinated agenda consisting of all five elements.

- 14: Doing all five things together delivered value—to be precise, an average of 14 additional percentage points of annual TSR if all five components of the transition agenda were successfully employed. Note that this was 14 points more than their peers. The spread over nonsurvivors was, of course, much higher. (See the exhibit.)

…And High Hurdles

Traditional companies start with lots of built-in hurdles. Incumbents are not used to reinventing their business models; after years of industry stability, their managerial skills and talent are generally honed toward methodical and incremental improvements within the existing paradigm. Furthermore, longstanding beliefs about how the world works can blind these companies to challenges from insurgents. Because established organizations are often hardwired to deny the need for disruptive change, they resist business models that upset the status quo. In addition, economic models based on scale positions or competitive capabilities usually convey substantial advantage—until they no longer do, and then they often actually work against a company’s ability to transform. It’s a tough combination for management to overcome.

Even when companies recognize the need for change and take action, they’re likely to fall into one or more traps. Most often, they fail to understand the full scope of the changes necessary or the implications for their value chains and business models. Poor timing, acting half-heartedly, or waiting too long before they move decisively are also common pitfalls. While there are cases of companies moving overly aggressively toward a new regime before it’s taken shape, the more common cause of failure is reacting too slowly or incompletely. Companies experiment without feeling the pressure to scale up. They adopt new technologies without evolving the business model. Or they make a single big bet without taking the time to fully understand how existing assets can be valuable in the endgame.

The initial response of newspaper and magazine publishers to the digital disruption of print media is an example. It took years of losing readers and, more critically, advertisers, before many companies responded effectively to the fundamental attack on their long-standing business models. The imaging industry is another example: remember Polaroid and Kodak? Most of the failures follow a well-documented pattern: denial, derisking, and decline. Even technology has not been immune: Wang Laboratories, Digital Equipment, and Gateway, among other major innovators, are no more.

How Thrivers Create Value

Less well documented are the thrivers: the one-third of companies that navigated an industry inflection to remain—or become—leaders in the new regime. Situations and actions differed enormously, but, in general, thrivers did five things well.

They engaged the threat. Thrivers understood the threat of disruption and its potential effects on their business models early, took preemptive steps to prepare—and disrupted on their own. For example, as airline deregulation took hold in Australia in the late 1990s, giving rise to low-cost carriers (LCCs) with significant operating and cost advantages, legacy carrier Qantas moved to start its own LCC, Jetstar Airways, while its major prederegulation competitor collapsed. This involved building an entirely new organization on the basis of very different operating principles and processes. Success was far from certain: the history of the global airline industry since deregulation is littered with bankrupt legacy carriers and failed LCCs. In fiscal year 2016, Jetstar had revenues of A$3.6 billion and generated earnings before interest and taxes of A$452 million—almost 25% of Qantas’s total.

Similarly, when Adobe saw the transformational potential of cloud-based services, such as software as a service, the company moved aggressively to a subscription-based product, revamping its engineering organization to function around one-month product cycles. Today, cloud-based products make up 85% of Adobe’s revenue, compared with 15% in 2012, and revenue is up by 33% by capturing share from those that did not make the transition as aggressively. Adobe’s shares have far outperformed its software industry peers, many of which have been slower to embrace the cloud.

They bet decisively (and they got the timing right). The magnitude of the response matters. When thrivers took action, they made investments equivalent to at least 10% of the company’s market cap, in the form of M&A or the capitalized value of internal investments, such as R&D. Bigger bets are certainly riskier, but in the face of disruption, such bets provide two distinct benefits. First, they ensure that the “new way” has enough heft to command organizational respect. Second, they signal to capital markets that the company has momentum and that a significant and growing portion of their business is benefiting, rather than suffering, from the disruption. BCG research has found material increases in the multiples awarded companies that act decisively compared with those that do not.

Consider Monsanto, for example. When big jumps in oil prices in the early 1980s disrupted the company’s large chemicals businesses, it changed direction. It spent 3% to 5% of its revenue annually through the decade on the R&D of genetically modified organisms—which it paid for by spinning off legacy businesses. Despite a tumultuous period in the 1990s, Monsanto emerged as an agricultural powerhouse with a genetic seed portfolio that helped the company more than triple its revenue in the first 15 years of this century.

They paid their way. Transformations take time and money, and investors are not known for their patience or charity. Companies that thrived found a way to fund their journey, either from substantive performance acceleration programs (which are often focused on cost) in the legacy business or through the disposal of assets that don’t fit the new world. In some cases, the magnitude of performance improvement and the clear skew of capital away from the core sent a clear and unmistakable signal: the future is elsewhere, this business’s role now is to generate cash to fund the journey.

Facing increasing competitive intensity and changes in technology, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) set about transforming itself from a broad-based health care organization with an emphasis on pharmaceuticals into a high-margin biopharmaceutical leader focused on specialty drugs. It paid the way by shrinking to grow and executing a multibillion dollar productivity improvement initiative over a number of years. It also launched a targeted M&A strategy to acquire high-potential drugs.

One bet that paid off big was the $2.4 billion acquisition of Medarex in 2009. Two drugs developed at Medarex and acquired by BMS were among the first immuno-oncology drugs approved by the FDA, in 2011 and 2014, for use in treating certain cancers. The acquisition was the start of an $8.3 billion bet on immuno-oncology. BMS’s market cap, which was $38 billion in 2007, increased 1.5 times, to $96 billion, at the end of 2016. (See “ Bristol-Myers Squibb: Reshaping the Portfolio to Create Superior Shareholder Value ,” BCG article, October 2016.)

Their top executives championed the new business. Thrivers all took decisive steps to protect and support the new business—and prevent the legacy organization from sabotaging it—until the venture could reach maturity. They did this in one of two ways. Either the “new way” was personally championed by the CEO, or the new business was kept independent from the legacy organization until sufficiently mature and successful. Under both approaches, strong leadership, well-designed incentives, and substantial top-down commitment were critical elements of success.

In 2011, the new CEO of Gannett—which, like many print media companies, had suffered major value erosion—launched a multifaceted transformation that has led to a four-fold increase in shareholder value as other publishers have continued to struggle, been sold, or gone out of business. In addition to taking the steps described above, she invested in building an adjacent business, which led to splitting the company into two publicly traded entities in 2015.

To help champion the changes and push the organization to pursue the transformation, she funded the building of an integrated digital capability at the corporate level and kept its budget isolated from the operating groups. She also personally approved the funding of key technology initiatives (such as a subscription paywall on the company’s websites and apps) to support the core business, sidestepping the usual financial analysis and approval process and accelerating execution by months.

They brought investors along for the ride. Investors that own stable businesses with predictable earnings typically value the large cash flows that such companies generate. And these investors often don’t appreciate the need for transformation—and the investment that accompanies such change—until the disruptive threat is affecting performance. Then they sell and move on, and the company’s valuation suffers the consequences.

Thrivers solved this problem by continuing to provide stable earnings and increasing payouts while delivering a transformed business model. They disrupted the company without disrupting the stock. They also used highly transparent investor communications to clearly articulate the transformation plan and lay out the milestones that management must meet. They reported regularly on progress. Some companies actively segmented their investor base and created outreach programs to cultivate support from influential and vocal members of the financial community while they managed key existing and target investors one-on-one.

Investors often don’t appreciate the need for transformation until the disruptive threat is affecting performance.

Best Buy, which managed a wrenching transformation during the meltdown of the consumer electronics retail segment, kept investors on board by talking the talk and walking the walk. The company aggressively communicated revenue and customer retention strategies that included turning the “showrooming” trend to its advantage, rolling out the “store within a store” model with major suppliers, such as Apple and Samsung, and expanding into digital and online retailing.

Best Buy had a simple message of customer focus and service, putting it this way in its 2008 annual report: “The core of our story, as we look to the future, is based on the hypothesis that we live in an age when technology is producing transformative change, enabling people to accomplish more with their lives than could have been dreamed possible two or three decades ago. We believe that to realize the many potential benefits of these changes, our customers will need a friend who can help them enable their dreams of digital connectivity—and that we will be that friend, through the talents of our employees.” Best Buy increased its dividends per share every year from 2003 to 2016 and is one of the few consumer electronics retailers to survive the shift online that brought about the demise of Circuit City and Radio Shack, among others.

Putting All the Pieces Together

Managing disruption is hard. The odds are stacked against a company, and it’s tough to succeed by taking half steps. Thriving through disruption requires an orchestration of five individually bold moves that must be executed concurrently.

Thriving through disruption requires an orchestration of five individually bold moves.

At Microsoft, for instance, former CEO Steve Ballmer and Satya Nadella, acting as senior vice president of R&D for online services and then executive vice president of the servers and tools business, laid a significant amount of the foundation; as CEO, Nadella built the house. Ballmer recognized the disruption to Microsoft’s long-standing and fabulously successful license- and desktop-based business model. And he did not underestimate the extent of the threat. He bet boldly, moving away from the Wintel model that had been at the root of the company’s success almost since its inception. He articulated and drove a vision of shifting from a software-sales to a cloud-based business model. He pulled top engineering talent from the server business and created a separate unit to build Azure, Microsoft’s cloud platform. Similarly, he set in motion the process of transforming Microsoft Office from a software product to a cloud-based service.

As reported in its 2010 letter to shareholders, approximately 70% of Microsoft’s engineers and most of its $8.7 billion R&D budget at that time were dedicated to cloud-related products and services. Microsoft paid its way with aggressive cuts to its cost structure and in 2010 began steadily increasing its quarterly dividend.

When Nadella took over as CEO in early 2014, he pushed organizational alignment through the senior team and the sales force using goals that were simple to define and measure. He also communicated these efforts to investors. Perhaps the most ambitious of the targets was achieving an annual revenue run rate of $20 billion from cloud services by 2018. (When he set the target in 2015, Microsoft’s cloud revenue was a little more than $6 billion; today, the goal is well within sight.)

Nadella also freed Office from Windows, made sure that Azure was reintegrated with the company’s servers and tools, and gave leaders carte blanche to grab from other areas of the business whatever resources were needed for success. He increased investment in infrastructure ahead of the curve and added another big bet with the acquisition of LinkedIn. He continued to make sure that investors were aware of and understood the transformation that was underway. Microsoft’s stock price has doubled since the end of 2013, outperforming the S&P 500 by almost a factor of two at a time when many legacy technology companies, slow to invest in cloud-based services and infrastructure, have seen their valuations lag by a factor of two or more.

The road to ruin is paved with past success; value creators blaze their own trail. To thrive in the face of disruption, companies must understand the scope of the change. They must also articulate a clear vision for their role in the disrupted future, make bold bets, fund the journey, champion the venture, and manage investors—and pull it all off in a carefully orchestrated program. It’s hard work. As the pace of change accelerates, more management teams will have to rise to the challenge.