In the quest for growth, traditional retailers in developed nations have been running up against a brick wall. Markets are mature, customers are fickle, competition is intense. Nimble new entrants with innovative sales and business models (online and offline) grab what incremental revenue there is. Incumbents flatline; share prices suffer.

In today’s retail sector, there certainly isn’t room for all players to grow. But our experience shows that retailers that are ready to experiment with new ways of working—including new ways of looking at, and using, current customer relationships and existing assets—can scale that brick wall. To do so, they need to overcome organizational barriers to change that have grown up over time (often for good reason), including strongly defined functional silos, an absolute commitment to scale in internal functions, and—quite simply—long-established, comfortable ways of doing business. The benefits of adopting an agile delivery model can be immense, enabling companies to capitalize on their scale while gaining the advantages of speed, customer centricity, employee engagement, and innovation that insurgents have demonstrated so effectively. By embracing the test-and-learn, self-managed teams of agile, traditional retailers can start to overcome the barriers to growth.

By embracing the test-and-learn, self-managed teams of agile, traditional retailers can start to overcome the barriers to growth.

Those who dismiss agile as a set of values and principles only for software development (its birthplace) or financial services (where it has migrated) should rethink their skepticism. Our work with a broad array of companies shows that agile principles travel well across industries and can help bring new solutions to difficult problems that large incumbents in many sectors are facing today. This is particularly relevant to the retail industry, where the variety of engagement models and ways of meeting customer expectations are key to building trust and loyalty.

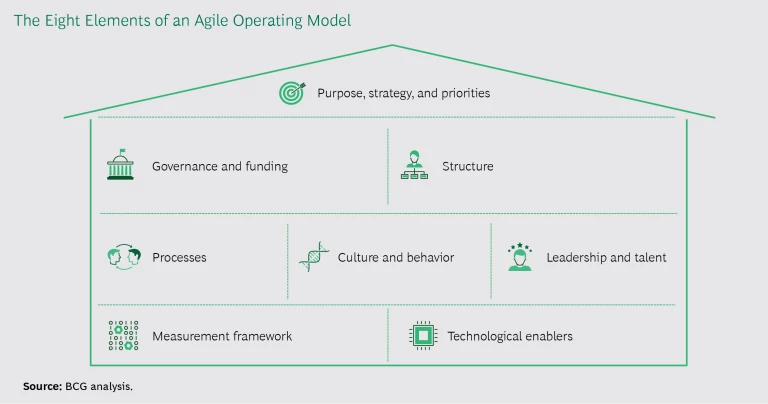

Agile delivery increases employee and customer engagement while reducing time spent on planning and administration (in meetings, for example). And it puts more resources into customer-oriented activities. Organizations that embrace agile have more doers, fewer managers, and, as a consequence, a lower cost base. Agile is not a simple or easy-to-execute way of working, however. It requires a number of operating-model changes in such areas as governance, processes, culture and behavior, and leadership and talent. But our experience suggests that companies that get it right can reduce costs by 25% to 35%, improve quality by 20%, and accelerate delivery of new products, services, and internal capabilities by 100% to 200%.

As agile starts to make its presence felt in retail, here’s how retailers—from department stores to big-box chains to grocers—can rethink their existing organizations to reignite growth.

The Limits of Existing Models

Retailers historically have juggled a unique package of challenges, from protecting thin margins, to managing formats and footprints, to staying abreast of customers’ shifting shopping preferences. Digital technologies and e-commerce have compounded the complexity and added new priorities, such as managing customer journeys and combating fast-moving online insurgents, to the mix.

Incumbents have used a combination of tools to address these challenges, including investing in critical new infrastructure (such as customer loyalty, data, and web capabilities), building scale in shared functions (such as finance, IT, and HR), and consolidating purchasing to forge more-effective supplier partnerships.

But even successful retailers may now be reaching the limits of the benefits they can wring from these moves. For one thing, the customer’s frame of reference has changed—the comparison set now extends well beyond a retailer’s traditional competitors—and people want greater personalization and customization to their individual preferences. For another, today’s organizations, even the successful ones, are still capable of becoming faster, easier to manage, less costly, and more innovative. For a third, companies have reached the bounds of so-called cross-functional coordination in functionally structured organizations. The best managers are assigned to an endless list of special initiatives and projects, and thus the responsibilities of their “day jobs” get pushed off until night—or never.

Agile Principles

A cross-functional organizational approach is all but a prerequisite for retailers looking to solve today’s challenges. Agile delivery methodologies have extended beyond software precisely because they comprise a set of organizational principles that successfully address many inefficiencies of the modern organization. (To learn more about agile, see the BCG articles “ Taking Agile Way Beyond Software ,” July 2017; “ Five Secrets to Scaling Up Agile ,” February 2016; and “ Agile to the Rescue in Consumer Goods ,” May 2018.)

Agile is built around autonomous cross-functional teams. These teams, which generally have no more than a dozen members, have both the skills and the authority to make decisions. With clear alignment on desired priorities and goals, they are given the autonomy to define how to solve a problem; they don’t need to wait for external specialists to weigh in or for a manager to bless their decisions. They operate with a high degree of transparency so that others can see what they are working on and know that it meets the desired business outcomes and company standards.

Team membership is full-time. Members are not being pulled in several directions simultaneously. They are fully devoted to the work of the team. If a team is waiting for input from a third party—a vendor, for example—it simply moves on to the next item in the backlog in the meantime. Or, in some cases, if the vendor is particularly critical to the team’s goals or could be a bottleneck, he or she can be pulled onto the team itself.

Agile focuses on productive action over coordination. Agile teams are engaged in activities that generate insights, value, and demand. With the focus on delivering a minimum viable product (MVP) at the end of each sprint, teams learn quickly whether they can reach the desired outcome. Team members have the power to act without running the gauntlet of gaining authorization from functional silos and writing countless memos and reports seeking approval. This means that they can swiftly produce an MVP and get feedback from the market. The relatively small size and cross-functional skill sets of these teams facilitate fast decision making, experimentation, and an ability to adjust course in response to feedback. Of course, even agile organizations require alignment across teams to ensure a seamless customer experience. But agile organizations maintain coordination through clarity in scope, boundaries, and accountability for outcomes rather than layers upon layers of functional approvals.

Agile values doers. In an agile organization, the locus of activity is the work of agile teams of doers. The members of these teams are the organization’s rock stars. To the extent possible, team members collocate (ideally physically but also virtually), building a sense of shared accountability that comes from proximity, with individual roles and responsibilities clearly communicated and understood by all. Each member of the team has specific expertise, and members take responsibility for tasks on the basis of their interest as well as their expertise. Everyone on the team needs to be an all-around contributor and support other members in their roles.

When a company adopts agile delivery, many managers become team members, and most enjoy their new roles—even though they no longer manage people—because they have more ability to create impact. The role of the manager in agile gives way to the product owner. (See “ Agile Development’s Biggest Failure Point—and How to Fix It ,” BCG article, August 2016.) This person helps define the team’s vision and manage its priorities and serves as the team’s link to the customer. But product owners are not traditional managers because agile teams, at their core, are largely self-managed.

Leaders have different roles. Agile organizations still maintain management layers above agile teams, but leadership takes a different form. Leaders establish context and strategy, allocate resources, and remove roadblocks. But what leaders do not do is equally important: they don’t get involved in the day-to-day work and instead leave decisions about execution to the teams. In other words, leaders define team objectives and how they will be measured, but they let the teams decide how best to meet those objectives. (See “ Agile Starts—or Stops—at the Top ,” BCG article, May 2018.)

Expertise still matters. While most of the work at agile organizations occurs within cross-functional teams, the specialists on these teams maintain their skills and knowledge through a horizontal, cross-cutting specialty group, often called a “chapter.” A chapter comprises members from different cross-functional teams who have similar specialties within those teams (for example, companies might have a marketing chapter). Among other things, the chapter sets standards to apply across the teams (such as marketing standards and best practices), ensures excellence in the chapter, and encourages the professional and career development of its members.

What Agile Can Look Like in Retail

Many companies in other industries have made the mistake of focusing too much on how agile methodologies, such as scrum or extreme programming, work rather than on the underlying philosophy. (See “ Agile Traps ,” BCG article, May 2018.) At its core, agile is a set of principles that guide an entire way of working, not a dogmatic prescription of specific structures and rituals. Five principles stand out, all of which are aimed at solving problems:

- A cross-functional approach

- Team empowerment and accountability

- Iterative work plans and release cadence

- An emphasis on feedback and learning

- A focus on evidence-based empirical outcomes

In retail, these principles may be applied differently than in other industries, and their application may even vary considerably between retail companies. Retail organizational systems accommodate a wide variety of critical business activities, from daily workflow at one end of the continuum to episodic undertakings at the other.

At its core, agile is a set of principles that guide an entire way of working, not a dogmatic prescription of specific structures and rituals.

Daily workflow activities include daily or weekly deliverables, routinized activities, individually small but collectively important decisions, and activities managed throughout the organization. They also typically involve tightly choreographed handoffs between stakeholders. For example, the promotional process usually entails a high-level strategy set by marketing or category merchandising and then a cascade of handoffs between multiple functions (commercial planning, operations planning, supply chain, and marketing, for instance), leading to in-store execution. Some handoffs happen sequentially and others in parallel, but each step requires a level of coordination that often benefits from more seamless cross-functional collaboration and teams.

At the other end of the continuum, episodic activities include longer-term deliverables that frequently entail major decisions and investments and can require teams to solve ambiguous problems. These activities usually involve project-based governance and already include cross-functional stakeholders in key roles. A category reset is one example. A strategic shift in the roles of digital and in-store channels is another. Such actions encompass everything, and everyone, from headquarters to in-store staff.

Agile has a role to play in both daily workflow and episodic activities (and in between), but that role is different in the two contexts. For example, promotions planning can benefit from cross-functional teams that make coordination and handoffs simultaneous and seamless, instead of spread out over time. This can narrow the planning window, decrease the overall time on task, speed time to market, and generate better outcomes. And by embedding responsibility in a cross-functional team, an agile approach to a category reset can reduce delivery risk and accelerate time to market while incorporating actual test-and-learn results into the planning process. In all cases, the team should regularly assess progress and evaluate if the initial outcome it set out to achieve is manageable.

The power of agile in retail is to put all staff in a position akin to that of an old-fashioned store owner—accountable for the overall operation and focused on customer satisfaction.

Each company needs to decide how best to apply agile principles across this span of activities in its own organization. But in general, we see a future in which:

- Integrated customer teams combine competencies (in corporate merchandising, operations, pricing, promotions, marketing, local merchandising, and analytics, for example) to streamline decision making and act as engines of success. In this model, a traditional merchant- or buyer-led organization could be replaced with department teams that are empowered to make decisions. This could enable greater accountability for a broad set of metrics and outcomes and create shared responsibility for the success of any one category or department.

- Component and platform teams coordinate access to, interaction with, and return on the use of shared resources (such as web presence, physical footprint, and store space).

- Expert teams and shared services provide high-value standard or bespoke services to the customer teams (such as custom research, loyalty, or data analytics).

- Operators manage day-to-day execution on the ground (in the store or distribution center).

The power of agile in retail is to put all staff in a position akin to that of an old-fashioned store owner—accountable for the overall operation and focused on customer satisfaction. Our vision leverages agile to deliver on this promise without sacrificing the scale necessary to be successful in a global, competitive, digital world. Implementing an agile mindset in retail means enabling a singular focus on customer value by dividing both regular workflow and episodic tasks into pieces that deliver value to customers and then organizing teams to execute each piece. It requires deploying experts on these teams to be closer to the decision making and breaking through communication barriers to accomplish work faster and give teams greater empowerment in the process.

Getting Started

Agile is just getting started in retail. Forward-looking retailers should experiment with different degrees and applications of agile teams and principles. We suggest a four-step roadmap.

Select a lighthouse project. Choose a pilot project or projects, taking into account the following criteria:

- Visibility. Consider the effect on company culture, the degree of business attention required, and the size and number of organizational stakeholders.

- Business Impact. Select a mission that can have a significant effect on the business and achieve measurable progress in eight to ten weeks.

- Relevance. Ensure that outcomes are relevant to the larger organization; people should be able to say, “This will work for me.”

- Readiness. Make sure that the business units and functional leaders are engaged and excited.

Choose the practices and principles to implement in the lighthouse project. Building enterprise-level agile eventually requires alignment of eight operating-model enablers. (See the exhibit.) This will ultimately entail a multiyear effort and, more than likely, a major change initiative. The lighthouse, however, can start by focusing on a few practices and principles—such as a flatter organization, cross-functional teams, new skills and career paths, continuous delivery, and automated testing—and try to get them right. A number of them will be new to many retailers.

Identify the right agile structure for the lighthouse. There are multiple ways to organize the agile structure, and there’s no single right answer for the entire retail industry. Each company needs to decide which structure works best. Agile is about learning as you move forward. Don’t be afraid to experiment or create new, hybrid structures. One of the leaders in agile organization, Spotify, regularly cites its ability and enthusiasm for trying new ways of doing things as a major organizational strength, as is its willingness to reset companywide norms according to the preferences of teams.

Define what scale means. As with other things agile, there are multiple paths to scale, depending on the success of the lighthouse and the lessons learned. Multidisciplinary agile teams can be formed, as needed, to manage specific projects. Companies can convert full lines of business to agile delivery. With companywide scale, multidisciplinary teams are implemented across the organization and put in charge of their own execution paths. Most retailers are a long way from this but could readily work toward agile project teams or lines of business.

Retail has always been a customer-first business. This is as true today as ever, but the scale of big organizations by definition puts distance between customers and corporate decision making. Agile can reinstill speed and nimbleness to organizations slowed by layers of decision making, and it can help bring large retailers closer to the customer again. It’s not a cookie-cutter approach. Every company will implement the core principles of agile differently. They will need to apply context-specific solutions and tailor how they lead their organizations through agile transformations because many of the changes affect people’s jobs and careers. But the benefits are evident, and the sooner retailers get started, the better, because the pace of change is only going to accelerate.