This article—the first in a series exploring the practicalities of going public—looks at the anatomy of an ideal IPO candidate and explores what is needed to prepare for life in the glare of the capital markets. Subsequent articles will examine what drives a high IPO valuation, what percentage of equity to float, whether and how to raise fresh capital, and other questions surrounding a decision to go public.

A few years back, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg wanted to postpone his company’s public offering because it clashed with his planned wedding date. Most CEOs mulling flotations have concerns that are less personal. Many question whether their companies’ revenues are high enough for a successful IPO. Others fear a listing won’t go well because they haven’t hit earnings thresholds yet.

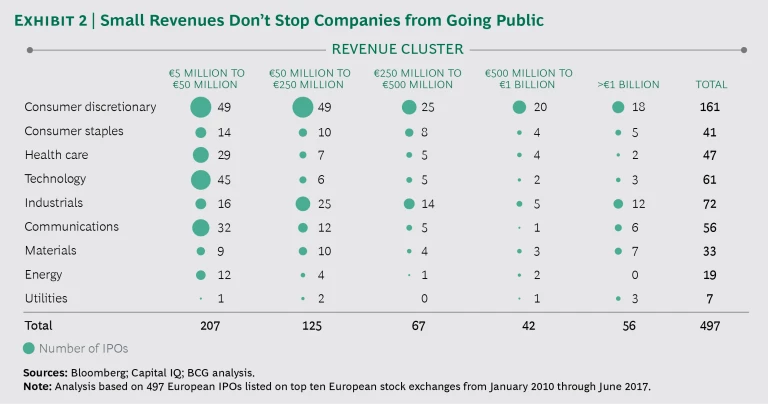

Neither concern is justified. Small top or bottom lines don’t stop companies from going public. New research by BCG finds that four out of five European companies that have recently gone public had annual revenues of less than €500 million in the year preceding their IPOs .

But things get trickier after flotation. One year out, smaller companies—those with less than €50 million in annual revenues—underperform their relevant stock market index. Big companies also risk under-performing after their IPOs. Fully 30% of companies with annual revenues of more than €500 million fail to perform better than the market in their first year of being public.

While we dispel myths about barriers to going public in this article, we also divulge the struggles of newly public companies, both large and small, which underscore that life in the public markets can be brutal.

Dispelling Doubts About Size

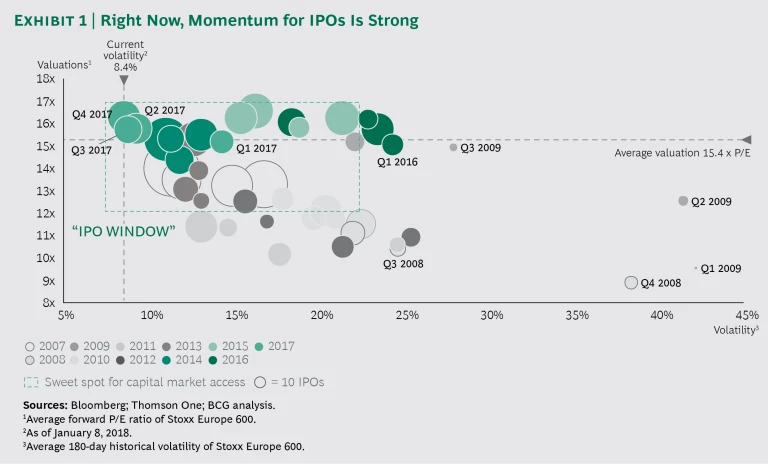

First, some background: after a year of political turmoil and market uncertainty in 2016, declining volatility created a positive environment for IPOs in 2017. In fact, all four quarters of 2017 landed inside the “the IPO window” (a favorable combination of high valuation and low volatility), helping the number and volume of IPOs to grow more than 50% compared with 2016. (See Exhibit 1.) The current mix of low volatility and high valuations should help carry the momentum into 2018.

But we wanted to know more about the indicators of success not only when going public but when being public. In particular, we wanted to debunk the myths about the required size of revenues and profits of IPO candidates. (See the sidebar, “Study Methodology.”)

Study Methodology

Our latest research helps to do that. While media and analyst coverage tends to focus on each year’s few large IPOs (in 2017, the US company Snap and the European company Pirelli sat at the top of their respective IPO league tables), our study finds that most IPO activity comes from much smaller companies. For our sample of European companies, the median revenues in the year prior to the IPO were €83 million.

It’s tempting to rationalize those low numbers by imagining that they apply only to technology startups whose owners are looking for fresh capital or early exits. But that would not be accurate. Regardless of industry, there is no hard threshold for companies to conduct a stock listing. IPOs of companies with less than €50 million in annual revenues are common in almost all industries. In health care, communications, energy, and technology, the highest number of IPOs in our sample were launched by companies in that revenue bracket. (See Exhibit 2.)

The evidence is much the same for profits as it is for revenues. More than 55% of the companies sampled had EBITDA of less than €15 million in the year prior to the listing. In fact, 40 companies debuted after posting negative EBITDA in the previous year. This includes some of the largest recent internet IPOs—German companies Zalando, Delivery Hero, and Rocket Internet, for example. There are candidates from long-established industries too; UK low-cost carrier Flybe was losing money before it went public.

Things Are Different After the CEO Rings the Bell

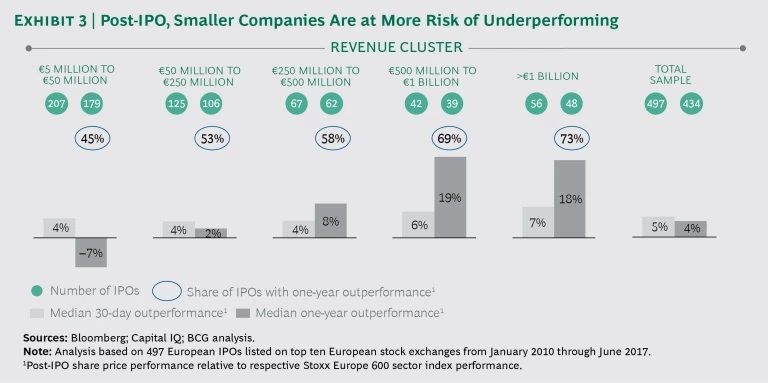

Getting to market is only part of the story, however. We also investigated the impact of revenue or profit levels on a stock’s performance downstream. Specifically, we analyzed how each newly public company performed compared with its respective Stoxx Europe sector index. (See Exhibit 3.)

At first, it looks as if size has no bearing on stock performance either. During the initial 30 days after the IPO, the median relative performance across all revenue clusters is positive and much the same for small and large IPOs. All clusters outperform their respective sector indexes by 4 to 7 percentage points.

But the picture changes substantially when the review period stretches to 12 months. One year out, companies with revenues of less than €50 million underperform (–7% median performance relative to their respective Stoxx indexes) while all other revenue clusters post positive performances overall.

The largest performance gains are achieved by companies with revenues of €500 million to €1 billion (19%) and above €1 billion (18%). (Strong performance in those clusters may be due to broader analyst coverage as well as less aggressive IPO pricing to secure successful share placements.)

But size—by itself—is no protection against underperformance. Although large companies outperform on average, there is significant spillage into negative territory in those clusters too. Among IPOs with more than €500 million in annual revenues, three out of ten fail to outperform the market in the first year. But the ratio is even worse for smaller IPOs: only about 50% outperform their relevant market indexes.

So what can companies do to minimize the risks of underperforming? We have observed that firms that go public and manage above-average performance afterward are skilled at juggling three interrelated activities.

Understanding the Future Investor Universe

To prepare their companies for life in the public markets, executives must understand who is going to invest in the planned IPO and what those investors will expect. A good starting point is to analyze peer companies’ shareholder structures to pinpoint prospective individual investors and investor groups (such as pension funds, asset managers, hedge funds, and retail investors).

The next step is to understand investors’ expectations. Do they anticipate constant dividend yields? Are they looking primarily for aggressive growth? Interviews with typical targeted investors will flush out the answers.

Articulating these expectations helps a company frame its future investor base—and, crucially, see itself not as it may have viewed itself historically but as investors perceive it. One example: an energy firm that had taken pride in the global span of its operations—from the Gulf of Mexico to the North Sea to the Middle East—learned from interviews with potential stockholders that they much preferred to invest in a business with a clear geographic focus. The company began to rework its portfolio and positioning accordingly.

Understanding the Importance of the Business Plan and Equity Story

Knowing what investors expect should influence the strategic and financial plan that the company presents to the market and the equity story it tells. For example, if the company decides to target yield-seeking investors, it should orient its dividend policy, capital structure, and business plan toward strong cash-flow generation. If the higher payout will limit the company’s ability to invest in growth, the equity story needs to reflect that fact.

Preparing a sound business plan and developing a convincing equity story definitely help offset the risks of going public. Often, both activities—if done thoroughly and with enough lead time before the IPO—trigger strategic, structural, and operational adjustments that take time to implement. Many successful companies start working on “yardstick” versions of the plan and story as much as 18 months ahead of the flotation date. Armed with fresh outside-in perspectives from potential investors, those companies then have time to make changes to fit their stories.

Developing a Sound Business Plan

A sound plan is crucial both before and after flotation—even if it can’t be disclosed to investors in most markets before the IPO. It helps prevent negative surprises prior to the IPO and lays the foundations for strong performance once in the market. In addition, a strong plan will be integral to the rating assessments as well as banks’ due-diligence processes ahead of the listing and forms the basis for predictable operational and financial results post-IPO. No surprise, then, that the plan must have clear initiatives and a detailed timeline—not to mention the full attention of the CEO and CFO.

Moreover, the plan must be granular enough to enable the management team to communicate effectively with the capital markets—for example, on quarterly earnings calls. It should describe ways to prepare the executives not only for the quarterly cadence of being public but for fast roll-ups of the numbers and careful messaging to shareholders. Once a company is publicly owned, the CEO and CFO in particular face constant surveillance by analysts, shareholders, and the broader public. Failure to deliver against market expectations—a function not only of the industry’s and the company’s performance but also of the information that the management team communicates—can land companies in deep trouble.

We recommend a three-step process for building a sturdy, durable business plan. The first step involves a rigorous examination of the substance of the plan—how it compares with market trends, whether it includes significant peaks (the “hockey stick” pattern), and how and whether those peaks can be explained.

The second step tests for ambition level—how far-reaching the plan is. It draws on external market data and benchmarks along with a view of best practices. It calls for detailed analyses versus the company’s direct peers, using actual financials and inputs from industry analysts.

The last step looks at how the company can strengthen its plan—which levers it needs to pull to boost performance and what improvements it can make in time for investors to recognize those actions ahead of the offering.

Crafting a Convincing Equity Story

At the same time that the company is building its business plan, it also has to “write” its equity story. This becomes its public pledge to the market as well as a unifying theme for the organization. Under the tight regulatory restrictions surrounding capital market listings, the story plays the central role in all pre-IPO communications to investors and analysts. It must be persuasive enough to attract investors offering high valuations—investors that often have the luxury of choosing among companies with similar profiles.

To make the story work, various parts of the organization must collaborate effectively. The strategy teams and investor relations groups often take the lead. But the company’s operating business lines and technical experts must also be closely involved to ensure that the investment highlights are backed by powerful and consistent proof points.

In conjunction, the finance team must ensure that all data is consistent with the business plan, the reported figures, and the IPO prospectus. As with development of the business plan, the CEO and CFO are integral to the story-crafting process. After all, they are the executives who will have to deliver the story—consistently and convincingly.

Crafting an equity story might seem easy: it’s relatively light on numbers, disclosure restrictions prevent detailed discussion of the business plan, and the story recycles what the company has already documented in its internal strategy-related documents.

But it’s not easy at all. We find that many IPO candidates do not have a coherent narrative at the outset. As noted earlier, the way that companies think about themselves doesn’t necessarily align with what capital markets care about most. The fact is, most investors and analysts aren’t swayed by typical descriptors such as market leader, innovation champion, unique, agile, lean, global, and of course digital. If such language isn’t backed up by substance, investors and analysts will dismiss it—and potentially discount the valuation.

What’s more, companies seeking to go public must paint a picture of the future without being able to share the details of their strategic and financial outlooks. Because of this limitation—as well as many other challenges—most companies that start writing an equity story soon find the activity far more challenging than they’d expected.

We have identified several best practices for crafting a strong story:

- Pick the right peers for comparison. Select public-market peers whose numbers and valuations will guide investors and analysts to your targeted valuation levels. The right peers will also serve as measuring sticks for your preparation work, setting the financial and nonfinancial bars that your company must clear in order to convince investors of its value.

- Challenge yourself. Ensure that each claim in your story can be compared with the claims that your peers make. By doing so, you’ll address the themes that are relevant to your potential investors and analysts. And you’ll validate whether your company truly has a unique position in its industry. This exercise helps you see where you can look for a premium compared with your peers’ valuations and where you need to strengthen your story.

- Prove your points. Thoroughly substantiate each claim, ideally by explaining the tangible initiatives that your company has implemented—such as recent M&A activity that strengthened your product offering or improvement plans that addressed operational challenges. Ensure that the initiatives behind your proof points—cost-cutting programs meant to boost margins, for example—are reflected in the financials at the time of the IPO so that you get credit from the capital markets.

- Show your commitment to value creation. Explain how your company’s strategic priorities (such as top-line growth, margin expansion, or cash generation) translate directly into shareholder value creation. Communicate clear ambition levels for all such drivers—payout ratios, for instance—to demonstrate your commitment to the market.

- Build a watertight financial section. Tailor your selection of KPIs and your presentation of financials to the issues that investors and analysts care about most. Make sure that the numbers are consistent with information provided in previous announcements.

There is plenty to do before the CEO of a newly public company can ring the bell. Yet no boss of a business that aspires to an IPO should shrink from the effort required. And none should be deterred by thinking that their company is too small or not profitable enough. But they must be alert to the risks of being public. The key to minimizing those risks is to get the preparation right. That starts with understanding exactly what target investors want. It then involves building a robust IPO business plan and, in tandem, crafting a persuasive equity story to communicate to the capital markets. All three aspects must work together: the plan needs to be tailored to the expectations of future investors, and it needs to reflect the equity story.

Up next: a look at the next stage in going public—how to structure the offering by determining which portion to float.