In a world newly awash in defense spending, the old ways of doing business aren’t going to work anymore. After years of shrinking budgets, global defense spending is expected to reach $1.7 trillion this year, the highest level since the end of the Cold War, according to Jane’s by IHS Markit . Some countries are increasing their defense budgets by as much as 10% annually. By our estimate, approximately $200 billion, or 40% of the accessible market, is currently up for grabs.

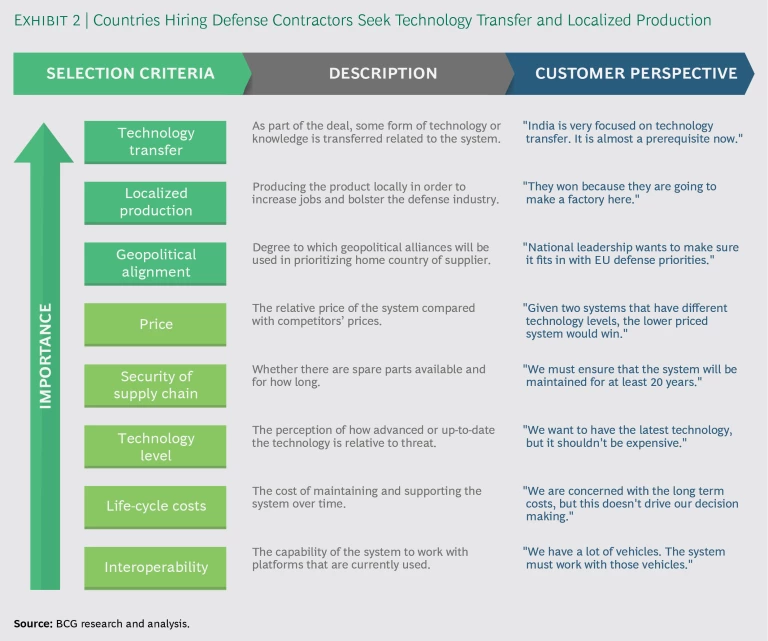

Countries are not only making greater investments in defense; they are also expecting more return on their investments. Unlike the way business was done in the past, today’s buyers want the defense contractor to invest in their country’s infrastructure, help develop their local defense capabilities, and diversify their economies. According to interviews we conducted with procurement experts in more than 20 countries, technology transfer and localized production are the top criteria for selecting a defense system, more important than capability.

To succeed, companies must acquire an in-depth understanding of the types of markets they want to operate in. Firms that weave themselves into the local tapestry stand to win in the long run.

New Ways of Doing Business

In the past, defense companies relied mostly on exporting and selling their products and services through government-to-government channels and direct sales from their home market, with headquarters calling the shots on which offerings to sell. To sweeten the deal, companies often included an “offset” agreement for a tangential project in the buyer’s country that employed local workers. Since headquarters made the key product decisions, country managers tended to act more like hotel concierges than business leaders, setting up meetings for visiting executives, making restaurant reservations, and relaying tidbits of information picked up at embassy cocktail parties.

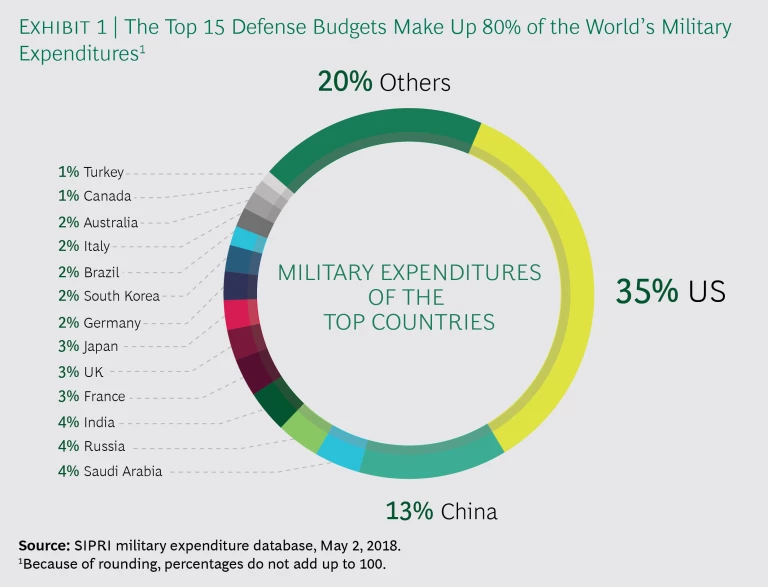

Those days are gone, replaced by a wholly different political climate. Spurred by geopolitical tensions and nationalistic ideologies, countries around the world are pouring more money into defense systems than they have in years. (See Exhibit 1.)

Leading companies have already begun reaping the benefits. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), 2016 was the first year the SIPRI Top 100 arms-producing and military service companies saw a growth in arms sales after five consecutive years of decline.

Along with these changes have come new ways of conducting business. Offsets are dying out as countries increasingly demand substantive local production and technology transfer from their defense contracts. (See Exhibit 2.) Instead of flying in and selling their offerings, companies must consider a localized business model, which includes partnerships, joint ventures, localized operations, and so on. That means being in-country, getting an understanding of the motivations of the decision makers, and establishing relationships within the broader community—universities, think tanks, state-owned research facilities, and other institutions. The company’s in-country leadership needs to take the lead in this far more complex endeavor.

Building such a meaningful local presence is no small undertaking. It requires understanding who the key decision makers are, what they’re looking for, and what types of investments will be necessary.

Different Strategies for Different Defense Markets

Since every country is different, companies need to tailor their localization efforts accordingly. Overall, however, markets can be categorized according to whether they are mature or emerging.

Mature Markets

These markets, which include the US, Europe, Japan, and Australia, have a well-developed industrial base and capable indigenous defense suppliers that are the darlings of their ministry of defense. Their engineering and manufacturing facilities employ thousands of local skilled workers, whom they would have to lay off if government contracts suddenly came to a halt. Moreover, the local champions have superior market intelligence and access because they are deeply embedded in the customer ecosystem.

Opportunities in mature markets run the gamut. The US, the world’s largest defense spender, has always been attractive to foreign defense companies. That is likely to continue: current opportunities are especially abundant owing to the projected increase in defense spending for the next several years after a decade of decline. This may also demotivate US companies from looking for work overseas, at least those companies focused solely on short-term objectives.

Europe, by contrast, is a story of too much capacity and little scale. When NATO urged members to commit 2% of their GDP to defense by 2025, some of the larger countries like Germany expressed reluctance to do so. Others, like Estonia and Romania, have made this commitment but lack scale, so 2% does not amount to very much. We predict that the overcapacity will eventually shrink the number of European players. Any defense company that wants to expand in Europe needs to focus on innovative and cost-effective offerings with a local champion. Return on investment, however, will still likely be low. By and large, the same holds true for countries like Japan, where foreign companies cannot conduct business unless they have Japanese partners.

In this environment, defense companies wishing to expand in mature foreign markets can take a few different approaches:

Partner with a local firm. This is usually a relationship in which the foreign company lends its capabilities to a local player to manufacture products that the local player would normally be unable to manufacture on its own. In exchange, the local player provides local access and connections. Although it’s a good option for exporters, it can confine the company to a niche market. For example, Raytheon has licensed in-country production of various missile defense programs to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries; Boeing Defense has a similar arrangement for the F-15 fighter aircraft.

Buy their way in. Some leading companies are spending large amounts to purchase midmarket firms to become a “local” company in multiple countries. This low-risk way to enter a market can be beneficial for the target firm as well, especially if it lacks the scale to compete against national champions. But the strategic reasons for the acquisition should go beyond market access—for example, building a global supply chain is also important. BAE Systems has spent huge sums to purchase a number of US and Australian shipbuilding companies; these local subsidiaries leverage BAE’s UK core in shipbuilding to expand the company’s presence in these markets.

Build an organic presence. This option is the most difficult and time-consuming because it means gradually building a presence through a series of relatively small acquisitions and then winning large contracts. Having sold defense systems to Australia since the 1950s, Raytheon made a small acquisition and founded Raytheon Australia in 1999. After two decades of small acquisitions and various major contracts, Raytheon Australia is now one of the largest defense contractors there.

Emerging Markets

These markets, in which we include Poland, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, various Southeast Asian countries, and India, differ from mature markets in some important respects. They have a strong demand for defense systems. They also have money to invest but, because of a less-developed defense industrial base and few local champions, lack the capabilities to build the equipment themselves.

Notably in these markets, national leadership, not government agencies, makes defense acquisition decisions. These leaders usually want to develop indigenous capability to preserve their sovereignty and to avoid dependency on foreigners who are in a position to dictate what they can buy. In addition, they want to get a good return on investment of their defense dollars and generally to bolster the economy through tech transfer, industrial diversification, training, and job creation.

Not surprisingly, developing a local presence in emerging markets involves quite a different set of considerations from mature markets. Companies need to:

Understand the customer’s selection criteria. Emerging markets make defense procurement decisions based primarily on two things: national security and economic development considerations. Countries focused on the former are interested in building a home-grown industrial base that has sufficient capability and capacity. They will generally want to work with defense companies with expertise in technology transfer and high-quality engineering and production.

Poland is a good example. Like several other eastern European countries, it has done little to modernize its defense industrial base since the days of Soviet dominance. Although the country has sufficient engineering and manufacturing capabilities for sectors like automotive, it lacks military-grade technology and therefore seeks companies that can provide technology transfer.

By contrast, some emerging countries focused on economic development are more interested in providing employment for their ever-expanding younger population. These countries therefore are looking for suppliers that can localize production in their markets.

One such country is Saudi Arabia, which imports almost all of its defense systems. One of Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman’s goals is to build a local defense industry. His Vision 2030 program aims to increase localized production to 50% by 2030, with the aim of transferring technology and creating highly skilled jobs for Saudis.

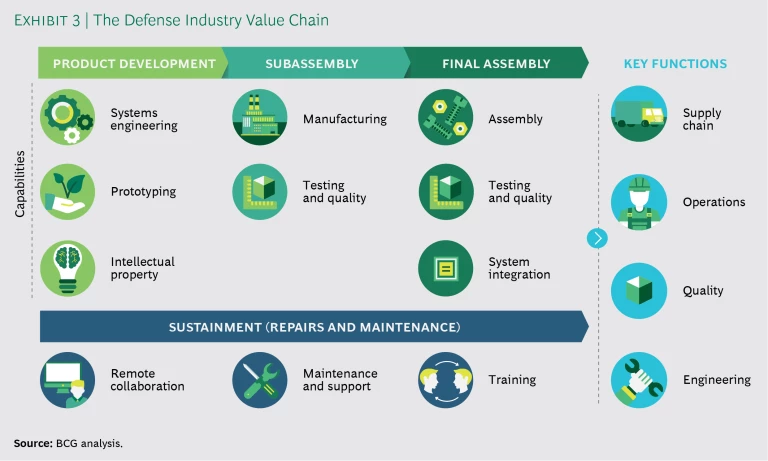

Keep value chain considerations in mind. While gaining market access is an important reason for targeting a particular country, it alone is unlikely to justify the large investments that localization requires. Companies also need to make sure that having operations in that country will benefit their global value chain. The maturity of the country’s industrial base will help determine which products can be produced there.

For example, an industrial base with sophisticated technology and advanced manufacturing capability can handle production of more technologically advanced defense components further down the value chain. (See Exhibit 3.) Other projects might focus on local production of certain components in-country, while still other projects might target on local assembly and testing. The competitive differentiator is technology transfer and a project or series of projects that adds sustainable value to the local economy at different points throughout the value chain.

Lockheed Martin’s Sikorsky Aircraft subsidiary invested in a production factory in Poland with geographical and labor cost considerations in mind. The company now sells this equipment globally at competitive pricing. Further, Sikorsky established its facilities in Colombia to provide regional depot-level maintenance and flight-training services for Black Hawk helicopter customers throughout Latin America.

Get multiple perspectives. Companies can all too easily become captive to their own viewpoints. This is especially true for large companies with many resources at their disposal in-country. That can make them less adept at spotting changes in markets, customer buying patterns, and competitors’ responses, and therefore less competitive. The companies that can expand their connectivity in-country to gain insights from different networks will more likely make smart decisions.

Be sure to get the perspectives of five different groups: the finance community; senior national leadership; think tanks; people in party politics in democracies (including the current opposition, and regional or local governments in countries with federal structures); and the intelligence and diplomatic communities. An inside view from each of these five areas will usually provide a good read on what is actually happening. It’s useful for companies that want to do business in Saudi Arabia, for example, to understand that the Crown Prince is very serious about achieving economic diversification goals: He set up an organization headed by investment bankers to vet defense acquisitions, and he made local production an explicit criterion for selection.

In some countries, however, it can be somewhat less clear what’s going on. Such is the case in India. The country is eager to modernize its industrial base in the face of geopolitical threats. But tensions across military operators, the procurement bureau, the current state-owned military industrial complex, and political leadership raise questions about whether it’s practical to expect them to work with western defense contractors.

Empower in-country leadership. In the past, each business unit in a multibusiness-unit company operated independently, pushing its own agenda to optimize sales. No longer: In-country presidents now need to steer product offerings to realize the overall goals of the company as well. This is not easy to do and can happen only if they are empowered to make decisions traditionally made at the business unit headquarters. This process means rethinking traditional organizational structures and revamping them for a changing customer reality.

Five Tips for Navigating Global Defense Markets

Whether the target markets are mature, emerging, or a combination of the two, pursuing international growth is a complicated business that falls outside many companies’ comfort zone. To navigate this landscape, it’s critical to:

- Focus on a few markets at a time. Every market has unique opportunities and complexities, with different buyers, defense requirements, government regulations, and economic considerations. Given these variables and the amount of investment required, it would be impossible to succeed in many markets at the same time. So we recommend selecting the three to five mature markets and the same number of emerging markets that are likely to provide the greatest financial return. This means thinking about not only the potential profitability of the markets in question but also global issues, such as supply chain footprint and economies of scope and scale.

It’s also critical to take into account the attendant risks, which tend to be higher in foreign markets than at home. In mature markets that have democratic governments, political and military views of the people in leadership positions can change with every new election cycle, and the size of defense budgets along with them; companies, therefore, need to ensure they don’t invest all their energy in one such market. In emerging markets, there are both financial and reputational risks, and missteps can be costly. Since it’s difficult to predict which markets will become less productive, a portfolio that balances risk and return is the best approach.

- Assess the competitive strategy. Defense companies should clearly determine whether their target customer has a need for their defense products and services. They also need to be able to articulate why they have a right to win in the target market—what differentiates their offerings from the competition. Sales efforts will more likely succeed if companies focus their efforts where their capabilities will be valued most, whether it’s top-notch engineering or localized production.

Companies also need to assess the sales strategy to determine whether it’s preferable to sell directly to the foreign government or to take an approach where the company’s government acts as an intermediary. The government-to-government approach—a bilateral agreement—often has strings attached regarding the type of exports, end use, and so on. But this approach may be necessary if any competitors are using it; otherwise, the company will be at a disadvantage. Note that many competitors, especially from Europe, lean heavily on their national government for support, so in those cases you are competing against a country, not just a company.

- Understand where the individual buyers are coming from. Companies need to find out who in each of their target markets is making the key military purchase decisions and how to influence the outcomes. Employees responsible for information gathering need to profile every person they interact with; that way, they’ll avoid being overly influenced by the last person they spoke to. Moreover, they need to analyze carefully how they process what they learn—a dose of skepticism can be quite useful.

- Keep an eye on costs. Developing a local capability can be expensive. The hosting country is unlikely to chip in, so companies that find ways to keep costs down are in a better position to compete.

- Start early. The investment in localization begins long before the sales pitch. It’s crucial to do due diligence, establish relationships, and do any other needed preparations, such as identifying local partners, well in advance of meetings.

Regardless of whether a company decides to pursue mature markets, emerging markets, or a combination of the two, international growth is a complicated business. No one can predict how customer needs will change in the years ahead, but companies that can create a viable local presence will be more likely to win an outsized share of the international market over the long term.