For James—a successful Filipino talent agent and former restauranteur who is in his late 40s—travel is a passion. It energizes and rejuvenates him. James tries to be on the road at least one week every month. And when he travels, James says, “It is all about dining and shopping.” He reads blogs to stay abreast of trends in destinations, food, and luxury brands, and he conveys his discoveries to friends who share his passions. James can afford to splurge on luxury—he’ll buy a Giorgio Armani suit. But what he really enjoys is the hunt for something unique. While shopping during a recent trip to Taiwan, for example, no purchase cost more than $40. But all items were local brands that couldn’t be found anywhere else.

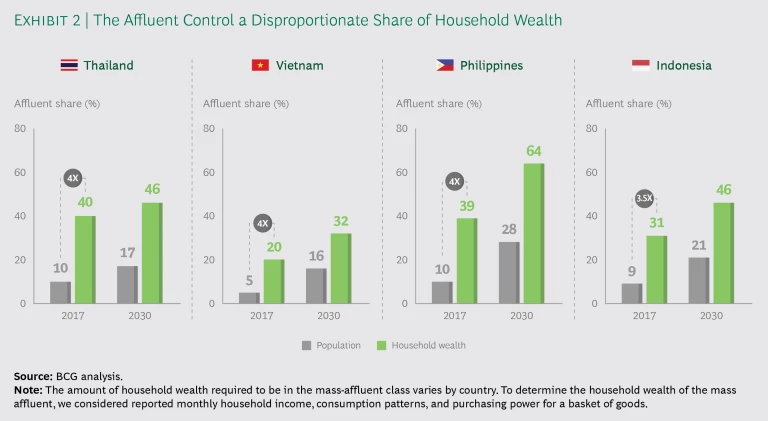

In many respects, James fits the profile of what we call the mass affluent—a market of affluent consumers in Southeast Asia that represents one of the world’s largest growth opportunities for consumer product companies. We estimate that 57 million people in this dynamic region have gained affluence—the purchasing power and intent to sharply increase their acquisition of a wide variety of premium and luxury goods and services. The mass affluent account for up to 40% of household wealth in major Southeast Asian markets and more than half of the total spending in premium and luxury categories. Today, these individuals constitute up to only 10% of the population in the region’s biggest economies, but by 2030, the ranks of the mass affluent are expected to reach 136 million and represent 21% of the population. We believe that companies in the region, as well as those outside it, should take a closer look at the mass-affluent market and plan to target it.

Who Are the Mass Affluent?

To understand the mass-affluent market in the ten-member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)—Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam—it’s important to set aside the typical Asian stereotypes: high-net-worth individuals who inherited their wealth or won windfalls in property and security trades and the lavish-spending ultrarich who are depicted in the movie Crazy Rich Asians. Indeed, high-net-worth individuals represent a minuscule minority of the mass affluent.

Research conducted by The Boston Consulting Group’s Center for Customer Insight, including a survey of about 6,000 affluent consumers and extensive ethnographic qualitative research in six major Southeast Asian countries, found that the majority of mass-affluent consumers are young and savvy. Two-thirds are under 40 years of age, and more than three-quarters graduated out of the middle class within the past ten years and earned their wealth as salaried professionals or business owners. Although they are starting to buy luxury goods, many are still in the process of trading up to premium products in categories such as personal care, food and beverage, and footwear. So these consumers are relevant not only for luxury brands, such as Chanel and Diageo, but also for companies such as Johnson & Johnson, P&G, Heineken, and adidas. The buying propensity of the mass affluent also tends to be more stable than that of the middle class during times of economic volatility.

The buying habits and preferences of affluent Southeast Asians can be quite nuanced and often don’t follow expectations. Plenty of the region’s nouveau riche spend ostentatiously. But most are like James: they buy premium and luxury products and care about the status they convey, but these consumers also do careful research to make sure the products are worth the price. They actively use digital media, but they also enjoy immersive purchasing experiences and make a disproportionately high share of their purchases while traveling abroad.

How Market Dynamics Will Change

As the mass-affluent class replaces the middle class as the driver of growth, the dynamics of Southeast Asia’s consumer market will fundamentally change. Categories such as passenger cars, cosmetics, and restaurant dining will become hot growth segments, replacing categories such as household appliances, baby products, and ready-to-eat foods; similar shifts occurred when China experienced a comparable demographic shift. (See The Age of the Affluent: The Dynamics of China’s Next Consumption Engine , BCG Focus, November 2012.) For companies that already consider Southeast Asia to be a major market, the best growth opportunities will be in mass prestige (or “masstige”) products, which convey luxury but are priced more affordably. Demand is also likely to surge for premium products, such as organic moisturizing creams, rather than mass-market skin care products.

The mass affluent are far more accessible than most companies realize.

For many companies, the prospect of reaching a relatively niche market that is dispersed across a vast region with a wide variety of languages and cultures may seem daunting. However, the mass affluent are far more accessible than most companies realize. Because these consumers are frequent travelers and heavy users of digital media, a remarkably high number of them across Southeast Asia’s markets share similar sets of values regarding what and how they buy. These consumers also tend to be concentrated in key city clusters. Therefore, they are a more accessible market than the middle class and will likely respond well to a regional strategy.

Sizing Up the Mass-Affluent Market

It’s important to clarify what we mean by mass affluent. We aren’t referring only to an income level. Indeed, many members of the affluent class would not be regarded as particularly “rich” by the standards of a developed economy. For example, an affluent Filipino reporting a monthly household income of about $5,500, when measured in local purchasing power, may appear to be in the upper middle class. However, households in Southeast Asian countries often significantly underreport their incomes. So we assessed consumption patterns as well as household income to determine the characteristics of the affluent. Middle-class families, for example, tend to sharply increase their spending on indulgences, such as snack foods and beverages, as their incomes rise. As middle-class families enter the ranks of the affluent, they greatly accelerate their consumption of premium and luxury goods and services, such as cars, liquor, restaurant dining, and travel. Using consumption patterns and household income as a gauge, we found that about 5% to 10% of the population in each Southeast Asian nation is affluent.

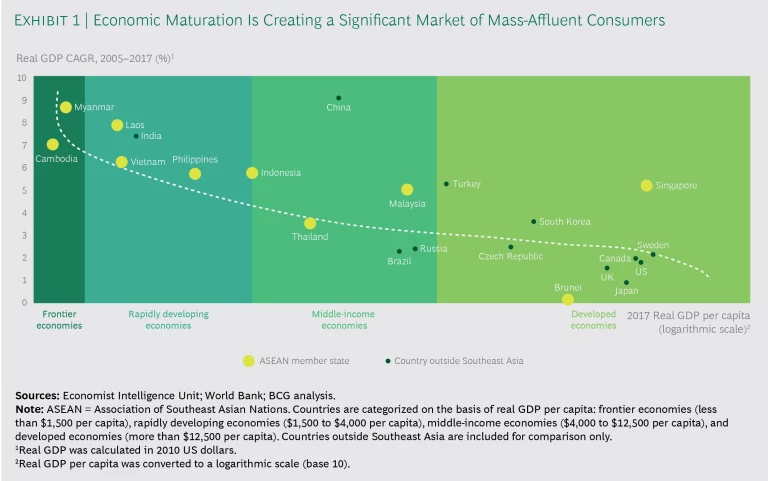

The member states of ASEAN had a combined 2017 GDP of $6.5 trillion, making Southeast Asia the equivalent of the fourth-largest economy worldwide behind the US, China, and India. If these ten member states were one country, it would have the world’s third-largest population. Moreover, many of Southeast Asia’s rapidly developing economies are maturing into middle-income economies, while others are on track to become developed economies. (See Exhibit 1.)

The region’s economic transition is a major reason for the expansion of the mass-affluent class. For decades, the dominant economic trend in Southeast Asia has been the growth of the middle class. But as countries’ GDPs have continued to rise, this large middle class has started to graduate to the affluent class. Now, the mass-affluent class is growing faster than any other income segment in the region—and the pace is projected to accelerate. In the region’s four most populous economies—Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam—the ranks of the mass-affluent class are expected to increase by 8% per year from 2017 through 2030, compared with 4% for the middle class. Over this period, the number of affluent people in those four nations alone is projected to grow from 46 million to 125 million, and their share of the population is projected to more than double, to 21%. In Vietnam, for example, 16% of the population will be affluent by 2030, compared with 5% now; this proportion is projected to jump from 9% to 21% in Indonesia.

The mass affluent already constitute a critical market. They control anywhere from 20% to 40% of household wealth in the most populous economies, and this share is likely to rise sharply to about 30% to 65% for key Southeast Asian markets by 2030. In the Philippines, for example, we project that the affluent will control 64% of household wealth by 2030. (See Exhibit 2.) These consumers are impacting some categories more than others. In Indonesia, for example, the affluent already account for a significant amount of all spending on restaurants (42%); leisure and travel (46%); watches, jewelry, and eyewear (49%); and cars (53%). The mass-affluent class is also particularly resilient during difficult economic times. While most consumers tighten their budgets during economic slowdowns, the spending of these consumers tends to remain steady or continue to increase.

Understanding the Consumer Psyche

The overwhelming majority of mass-affluent Southeast Asians are millennials: 64% are under the age of 40, and 24% are younger than 25. They have also worked for their wealth. The percentage of salaried professionals ranges from 50% in Indonesia to 86% in Singapore. Business owners constitute the second-biggest cohort. A surprisingly small percentage of people—less than 5%—inherited their wealth, except in Thailand, where a greater proportion has family wealth. In addition, less than 10% gained affluence through investment earnings. The affluent also tend to live in urban centers more than the members of other income groups do. About 80% of Vietnam’s affluent live in cities with populations of at least 1 million, for example.

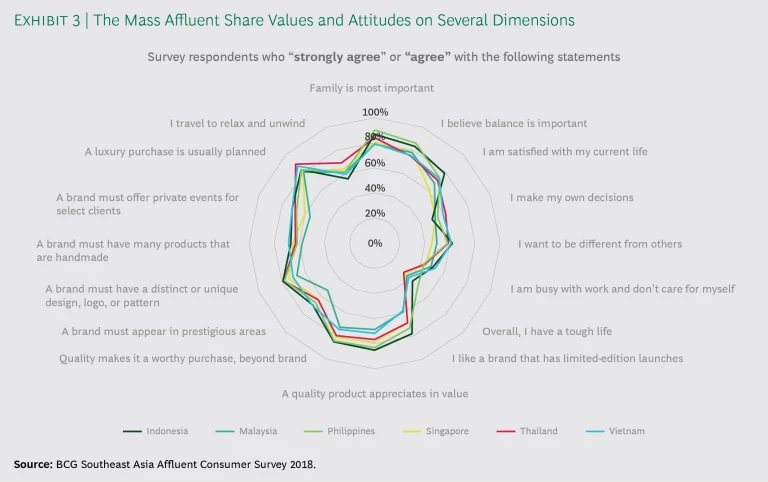

Despite the region’s immense cultural and economic diversity, we found that the mass affluent have strikingly similar views on lifestyle topics and attitudes toward work. These similarities are fostered by their use of social media (where they keep one another abreast of new products and fashion trends and share opinions) and their travel experiences. By margins ranging from 80% to 90%, for example, the affluent consumers we surveyed in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam agreed that they want to buy products and have experiences that differentiate them from others. We also found widespread agreement that balance is important and that they would rather enjoy life now than worry about the future. Even so, the respondents broadly concurred that they don’t purchase luxury brands just because such products are part of their lifestyle. These sentiments suggest that the affluent want a luxury lifestyle—but one that they define themselves. (See Exhibit 3.)

How long individuals have been part of the mass-affluent class influences them more than their country of origin does. Indeed, we found that those who have been affluent for more than ten years have grown more accustomed to their status and gained experience as consumers. As a result, these “experienced affluent” individuals tend to plan their purchases more carefully, and they are less swayed by emotion than the “newly affluent”—those who have become affluent in the past ten years. Experienced-affluent consumers want more than just a luxury brand. They are willing to pay premium prices to get quality, and they assert their individuality, spending more for a brand that reflects their values and aligns with their self-perception. They are also more interested in setting trends than following them. An additional difference is that newly affluent consumers increase their spending on items such as skin care products, cosmetics, and international travel. But as they become experienced-affluent consumers, they tend to focus on fine dining and luxury goods—such as watches, jewelry, and liquor—that reflect more refined tastes. (See Exhibit 4.)

The percentage of experienced-affluent consumers is likely to increase across the region. We project that by 2030, 47% of mass-affluent consumers will have held that status for more than a decade, compared with only 31% now.

Six Common Behaviors of the Mass Affluent

We have identified six behaviors that are exhibited by the majority of affluent Southeast Asians and that are extremely relevant for marketers. Specifically, these consumers are embracing “premiumization,” searching for quality and value, seeking exclusivity, relishing immersive experiences, using digital media, and traveling frequently.

Embracing Premiumization. Over the past decade, the main reason for the rise of Southeast Asian markets was the expansion of the middle class. When consumers crossed that threshold, they purchased certain products—such as smartphones, cosmetics, branded liquor, and frozen yogurt—for the first time. Companies offering these products made it their goal to penetrate this new market and drive sales of their products. As these consumers become part of the affluent class, they shift to purchasing more expensive products within the same categories, a process we call premiumization. To reach these consumers, companies must appeal to their desire for better, more distinctive products that speak to their new, higher status.

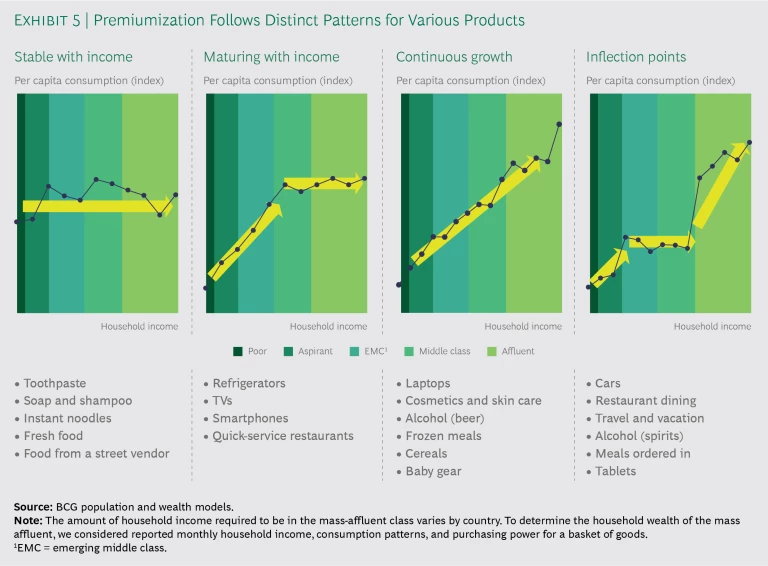

Affluent consumers spend considerably more in some product categories than others as their household incomes rise. Consumption patterns become evident by graphing income-consumption curves. (See Exhibit 5.) For some basic products, such as toothpaste, shampoo, and instant noodles, spending by Southeast Asian households remains very stable as incomes rise. For other products, such as refrigerators, TVs, and smartphones, spending experiences a step change at an income inflection point and then stabilizes. For example, middle-class consumers may upgrade their refrigerator from a basic two-door model to one with four doors and an icemaker. But they will not upgrade again as their incomes increase, even if brands add incremental features and frills. The income-consumption curve for other products is more linear: spending on laptops, cosmetics, and beer, for example, increases steadily as household incomes rise. Yet spending on cars, restaurant dining, travel, and spirits dramatically accelerates as consumers enter the ranks of the affluent—and keeps rising in step with increases in income.

It is crucial that companies understand the income-consumption curve for every one of their products and then match each product’s price ladder to that curve. If a particular product has a linear income-consumption curve, for example, companies should ensure that they offer products at each rung of the ladder to make it feasible for consumers to upgrade. Heineken provides an example. The company markets a variety of beers at price points that target different consumer segments in Southeast Asia. Its portfolio in Vietnam, for instance, starts with budget brands (such as Tiger Beer priced at about 50 cents a can) and extends to high-end beers (such as Heineken and Affligem, costing $1 to $2 per bottle) with other brands at key price points in between. This rather linear price ladder makes it easy for consumers to upgrade as they gain affluence, and it has helped establish Vietnam as Heineken’s second-biggest market worldwide. Brands without price ladders that match the upgrading pattern of consumers run the risk of losing their customers to competitors as incomes rise.

Searching for Quality and Value. The stereotype of affluent Southeast Asian consumers showing off their wealth with designer labels is badly outdated. Although the newly affluent frequently associate a top brand and high price with quality, experienced-affluent consumers are more discerning. Indeed, they are barely more brand conscious than members of the middle class. For instance, Justin, a Malaysian construction company executive and father of five, is an experienced-affluent consumer. Because he already owns standard luxury goods that he wears to business meetings or parties, he now buys luxury products “with a view of them as an investment.” Roughly seven in ten respondents to our survey agreed that quality is important if a luxury brand is to be a “worthy” purchase and that it should retain its value or appreciate. These considerations far outweighed respondents’ concerns that the brand had a reputation for being very expensive and for not offering discounts.

More-experienced-affluent consumers search for tangible proof of value, such as workmanship, the use of advanced technologies, or the use of special or sustainably sourced materials. Luxury brands are addressing this desire for craftsmanship, functionality, and quality ingredients. Brands such as Forever Living Products and The Face Shop, for example, promote organic beauty and skin care products made from aloe vera and other natural ingredients. Guerlain and Loewe seek to assure consumers that their products follow responsible sourcing practices and have established ethical and sustainable procurement guidelines for animal skin.

Mass-affluent consumers tend to see products as a means to differentiate themselves.

Seeking Exclusivity. Mass-affluent consumers tend to see products as a means to differentiate themselves, and they therefore seek out goods and services that are unique. Susan, a Singaporean in her mid-30s, told us that she has a whole room filled with bags, purses, and perfumes and that she buys limited editions “for the thrill of it.” Her collection includes a purse that is one of only two made in the world. “It’s so small that it can’t even hold my mobile,” she said.

Many newly affluent Southeast Asians care most about following trends and owning the same brands as their peers. However, as these consumers mature, they increasingly prefer goods that few others have and seek out exclusive and niche, harder-to-find brands. Cindy, a former marketer in her mid-40s and a mother of three children, told us that when she was younger, she was a “hoarder” of luxury brands because it was “fun and exciting” and “a way to connect with the group.” Now, she says that “it can be really embarrassing” to go to a party and see someone else carrying the same designer purse. “I am past owning the big brands,” said Cindy. “A luxury purse needs to fit my personality. It should be who I am.” She said that she bought her latest purse in a Barcelona boutique because it is “elegant” and “not dull, but also not flashy.”

In fact, our research found that as incomes increase, the affluent who previously bought well-known consumer brands are passing over well-known premium brands and gaining the confidence to move directly to superpremium, niche, and boutique brands. Instead of shifting from an inexpensive whiskey to a premium blended Scotch, for example, these consumers are buying high-end single malts. They are also spurning designer labels and choosing tailor-made or made-to-order brands, such as bespoke Gyunel and Ong Shunmugam dresses. Women are seeking out niche cosmetics and skin care products, such as those made by the Korean brand Isa Knox.

To meet this demand for exclusivity, luxury brands are launching more limited or special editions. Rolex and Patek Philippe, for example, are forming partnerships with artists to create small quantities of distinctive products. And as part of its Masters collection of bags, Louis Vuitton has formed an exclusive collaboration with the American artist Jeff Koons. Some companies are also customizing products or increasing exclusivity through access. Hermès, for example, tightly limits access to VIP events, and the product selection depends on customers’ status with the brand.

Relishing Immersive Experiences. For many of Southeast Asia’s mass affluent, an immersive experience can be as important as the product itself. Jasmine, a tax consultant and university lecturer in her early 30s who is married with no children, explained that she visits branded stores when buying a luxury product because “they make you feel special”: sales agents are “so soft-spoken, sensitive, and knowledgeable—unlike in a department store.” Michael, a Singaporean in his mid-40s who is in the telecommunications infrastructure business, described himself as passionate about Burberry: “The store visits take me someplace else. It’s such an integral part of the brand experience and what the brand means.”

A number of experiential factors are important in order for a company to establish a brand or product as premium or luxury among these consumers. These factors include not only the store location and level of service but also the types of special events and whether or not these consumers personally identify with the brand’s marketing story. When we asked affluent consumers what makes a brand premium to them, “I identify with the product and its story” was one of the top responses. This sentiment was especially true among those who are experienced-affluent consumers.

Winning brands are deploying a variety of strategies to create immersive experiences.

Winning brands are deploying a variety of strategies to create immersive experiences. Premium and luxury brands—such as MiuMiu, Fendi, and the Makeup Store, for example—are opening pop-up stores in key locations near Singapore’s Orchard Road to demonstrate their brand stories. Diageo is opening experiential, invitation-only retail stores for connoisseurs to sample and learn about rare and reserve Johnnie Walker whiskeys. Other brands are offering “factories in a store,” which custom-make products for customers. Le Labo, for example, hand blends perfumes in front of customers, enabling them to share in the experience of preparation. Online channels and physical stores are also increasingly deploying digital technologies, such as augmented and virtual reality . In Burberry’s new flagship store in Beijing’s Sparkle Roll Plaza, for example, customers are surrounded by giant video screens for projecting fashion shows, musical performances, and elaborate holograms.

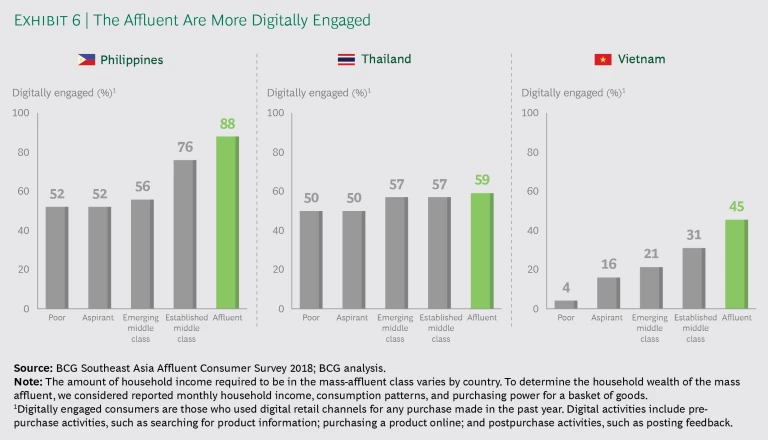

Using Digital Media. Digital media plays a more critical role in the purchasing decisions of the mass affluent than it does for other income segments. (See How the Digital Revolution Is Integrating Southeast Asia’s Consumers , BCG Focus, September 2018.) In the Philippines, for example, 88% of respondents told us that they used digital channels in the previous year to perform some action—such as searching for information, buying a product, or posting feedback—related to a purchase. This compares with 76% of established middle-class respondents and 56% of emerging middle-class respondents. (See Exhibit 6.)

In Vietnam, for example, 45% of affluent respondents told us that they used digital channels, compared with 31% of respondents in the established middle class and 21% in the emerging middle class. (For an explanation of income groups in Southeast Asia’s four most populous countries, see “BCG’s Method for Classifying Household Income Segments.”) This disproportionately high level of digital engagement makes the internet a key channel for influencing affluent shoppers.

BCG’s Method for Classifying Household Income Segments

BCG’s Method for Classifying Household Income Segments

A model developed by BCG’s Center for Customer Insight segments the populations of countries into five groups on the basis of monthly household income, census data, and purchasing behavior. The income segments are affluent, established middle class, emerging middle class, aspirant, and poor.

The income bands for these segments are different in each country, since they measure the purchasing power for a basket of goods. In Southeast Asia’s four most populous nations—Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam—the percentages of people in each income segment are as follows:

- Affluent. Across all four countries, an average 9% of the population is in the highest income segment, ranging from 5% in Vietnam to 10% in Thailand.

- Established Middle Class. Across all four countries, an average 12% of the population is in the second-highest income segment, ranging from 10% in Indonesia to 21% in Vietnam.

- Emerging Middle Class. Across all four countries, an average 5% of the population is in the middle income segment, ranging from 14% in the Philippines to 36% in Thailand.

- Aspirant. Across all four countries, an average 35% of the population is in this income segment, ranging from 18% in Vietnam to 48% in Indonesia.

- Poor. Across all four countries, an average 18% of the population is in the lowest income segment, ranging from 8% in Indonesia to 36% in the Philippines.

The population of middle-class and affluent consumers (MACs) in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines comprises the emerging and established middle-class and the affluent segments. But in Myanmar and Vietnam, it comprises only the established middle-class and affluent segments. In Indonesia, MAC households have monthly incomes exceeding $224. In the Philippines, these households have monthly incomes exceeding $465, in Thailand $442, and in Vietnam $660.

In fact, the internet is by far the most important source of product information for Southeast Asia’s mass affluent. About 60% of respondents said that official brand websites are among the top sources that inform their purchasing decisions the most, followed by online shopping marketplaces, such as Amazon and Lazada, and recommendations on social networking sites. That compares with 26% who cited “advice from friends, colleagues, classmates, and parents” as among their most important sources of information and 7% who cited TV ads. Only 12% cited physical, point-of-sale retail outlets. The digital interactions of affluent Southeast Asians evolve as they grow more experienced. Newly affluent consumers are significantly affected by famous fashion bloggers and public social media, but those who are more experienced pay more attention to trusted online circles and tend to purchase through private channels, such as a closed adidas group on Facebook or private WhatsApp groups.

The affluent also actively seek to influence others through digital media. About one-third of the respondents in Vietnam, for example, said that they “always” share their cosmetic recommendations with people they know online or in person, and half reported that they “sometimes” or “usually” share their opinions with acquaintances. These behaviors were also particularly strong when it came to premium items, such as watches, alcohol, skin care products, and jewelry. When asked which channels they use to share recommendations, about half of the affluent respondents said that they use messaging apps, such as Microsoft Messenger and WhatsApp, or social media sites. They also said that they usually post in private chat groups. “There are a bunch of people like me,” explained Jaydren, 40, a self-described adidas fan and a project manager for a construction company. “We know each other in our closed group, and people trust you in the fan club.”

Because affluent consumers are comfortable with digital channels, they make a significant percentage of their purchases online. In Thailand, for example, these consumers make about 50% of their fashion, skin care, and cosmetic purchases online. They even purchase jewelry, watches, and spirits online more than 40% of the time. The main online channels are mostly official brand websites and online marketplaces, followed by social media groups and other specialty websites. When it comes to very premium products, the affluent prefer to shop online through trusted circles rather than public marketplaces. For example, Eric, who is 43 and an experienced-affluent consumer, said that he recently bought a Patek Philippe watch online through his trusted Instagram network.

Active online shoppers seek experiences that combine online and offline channels.

Even active online shoppers, though, still enjoy shopping in conventional, brick-and-mortar outlets. In fact, they seek shopping experiences that combine both online and offline channels, as 62% of respondents confirmed. Seventy-three percent said that they like to buy products online and physically pick them up in stores. Sixty-eight percent said that they look online first to compare prices, and then they make purchases in person.

These findings indicate that consumer product companies should thoroughly define their digital strategies and find ways to integrate their shopping experience across offline and online channels. This is particularly true with luxury brands. Companies need a robust online presence to enable consumers to discover their products in both official and unofficial channels, but it is also critical that brands maintain some level of exclusivity to protect their image. Companies should also use affluent consumers as digital influencers by actively engaging them through social media. In Vietnam, for example, brands heavily promote returning expatriates, who are known as Viet Kus, as Instagram personalities to influence online buyers.

Traveling Frequently. The mass affluent are frequent travelers and globally connected. They make 12 international trips a year, on average—nearly half of them for leisure. Travel spending increases sharply when Southeast Asians enter the ranks of the affluent. A Thai household’s average spending per trip leaps nearly ninefold when the family graduates from the middle class to the affluent class.

The affluent also love to shop while on the road. Affluent Southeast Asians make about 40% of their purchases of goods such as cosmetics, watches, jewelry, and skin care products while traveling. “All of my international travels have to have a shopping component to them,” said Jen, 27, a Singaporean marketing manager. She and a friend visit Bangkok every two or three months, and they buy “a suitcase of stuff.”

The type of travel changes as affluent Southeast Asians become more experienced consumers. Instead of focusing on famous tourist spots—what’s known as “the checklist circuit”—they seek out destinations that offer authentic local culture and immersive experiences. Instead of taking group tours, they travel independently. And they shun tourist traps and seek out niche retail outlets instead.

We also found that the region’s affluent consumers keenly understand what to buy where. New York tends to have the best prices, according to survey respondents, while Hong Kong, London, Paris, and Shanghai are preferred for convenience, the availability of luxury goods, and being “family friendly.” Milan, Seoul, and Tokyo, by contrast, have reputations for being the best “one-stop shops,” having “authentic” products, and the “latest trendy products.” Erni, a 39-year-old Indonesian, said that when her family of five travels to a place such as Bangkok, they just do some quick planning and hop on a plane. When they travel further, however, she and her three high school–age children plan their trips carefully around shopping. They research not only which products and brands to buy but also where to buy them. Erni said that Dubai and France are the best places to buy essences. When they visit Japan, her son likes to buy special samurai trousers and jeans that mold to his body shape. They already know which stores they will visit during an upcoming trip to the US.

Another reason for buying abroad is confidence in a product’s authenticity. Mahruba, 36, a Malaysian who has two children and owns a travel agency, said she avoids the US for luxury purchases because “you always have this image of famous US brands selling at a huge discount.” Instead, she buys in Europe, where she knows that she will “get the latest designs and more niche and exclusive products.” Shahne, an Indonesian real estate executive, said that he trusts buying 30-year-old Hibiki whiskey, which his family keeps on hand for special occasions, only in Japan. In fact, Tokyo and Seoul have emerged as among the top shopping locations—taking over from Hong Kong and Singapore—for affluent Southeast Asians across most major luxury categories.

Premium and luxury brands are aggressively pursuing the traveling affluent. Some brands offer cultural training for staff in key global shopping cities and hire speakers of Southeast Asian languages. Leading brands are visible in social media channels for travelers, and these brands make sure that customers can use Southeast Asian payment systems, such as Mynt for Filipinos and Alipay for Singaporeans and the region at large.

Targeting the Affluent

As the action in Southeast Asia’s enormous consumer market shifts from the middle class to the affluent class, there will be profound implications for virtually every provider of consumer goods and services. Even though members of the affluent class will remain a minority of the region’s population, they will become an increasingly meaningful share of the target market for a wide variety of products. Companies must prepare not only to meet exploding demand in new product categories but also to shift to masstige and premium products in other categories. In addition, companies must master new ways to market products—ways that appeal to a consumer psyche that is dramatically different from that of the middle class.

Companies must appeal to a consumer psyche that is dramatically different from that of the middle class.

We offer six recommendations for how all consumer product companies—not only luxury brands—can pursue the affluent. (See Exhibit 7.)

Develop a regional strategy to target the affluent. Because the region is highly diversified and covers a wide area, Southeast Asia’s affluent population may appear to be a collection of niche markets. However, since many of these consumers live in urban centers and exhibit similar behaviors—such as using digital media and traveling frequently—it is entirely feasible for brands to create a regional strategy that reaches a very high share of the area’s mass-affluent consumers as a collective target group.

Define a premiumization journey. Companies must clearly understand the income-consumption curves for their products: Do these curves remain stable as household incomes increase, rise steeply as incomes grow, or increase and then plateau at a certain point? Companies must use the shape of the curve for each product to plan their own price ladders—including the right premium and luxury price points—in order to make upgrades accessible to their customers.

Offer some form of exclusivity. For luxury goods and services to command premium prices, they must connote exclusivity. Companies can convey this by restricting availability—manufacturing a limited edition of a product, for example, or crafting a product by hand. Companies can also restrict access to goods by holding private events for select clients. Exclusive events can be particularly useful for local retailers that have little control over the products they sell.

Use digital channels. Consumer product companies should ensure that they have a strong public digital presence that goes far beyond their own websites. Companies can accomplish this by taking several steps: using social media and chat groups (such as Line, WhatsApp, and Instagram) to infiltrate the private circles of sophisticated affluent consumers; engaging with fashion bloggers and influencers to promote their brands; and, appreciating the powerful influence that affluent consumers have on one another, encouraging them to communicate and share their opinions in public social media forums. However, to guarantee that brands maintain an exclusive cachet, companies should still control access—such as by allowing only certain products to be purchased online—and create an integrated experience with physical stores.

Companies should think of travel as an important channel for reaching the mass affluent.

Target travelers. Companies should think of travel as an important channel for reaching Southeast Asia’s mass market of affluent consumers. Airport duty-free shops should be viewed as outlets for selling much more than cosmetics and spirits. Brands should identify key international travel hubs and establish a presence so as to engage travelers early in their journey. Global retail outlets should cater to these consumers by having staff that speak their native languages and ensuring that purchases can be made through their local payment platforms.

Build a social license to operate. Consumer product companies must not lose sight of the fact that the wealth gap in much of Southeast Asia remains wide, and rising inequality can lead to a social backlash over time if incomes among the middle class stagnate. Companies pursuing the affluent must be sensitive to this reality in their marketing and build a social license by demonstrating clearly that they are contributing to broader economic development and social inclusion. They can show this by pursuing sustainable, local sourcing of materials; creating jobs by manufacturing products locally; and supporting social programs in the communities in which they operate.

The affluent are the New Age premium and luxury consumers. They are mostly young, independent, and confident in their choices of brands and in their self-earned wealth. Companies that take into account the common values and behaviors among the affluent—and use digital and travel channels to reach these consumers—will greatly increase their ability to succeed in what promises to be one of the greatest growth opportunities in Southeast Asia’s economy.