As the Brexit deadline of March 29, 2019 looms, the biopharmaceutical industry is bracing for the worst: a so-called “hard Brexit,” in which the UK would leave the EU’s single market without a formal trade agreement in place. This would affect core aspects of biopharma’s business, from licensing and manufacturing to clinical trials and distribution. With 45 million packs of medicine supplied from the UK to the EU every month, and 37 million from the EU to the UK, the disruption to the supply and flow of medicines could be substantial.

And it would coincide with an already busy time for biopharma. Companies are scrambling to meet the February 9, 2019 deadline for the EU’s Falsified Medicines Directive, which, like Brexit, requires significant changes to product packaging. And many companies are managing corporate development activities—with regulatory implications—such as portfolio pruning (as we’ve seen with the recent Novartis–GSK and BI–Sanofi asset swaps) and the integration of recent acquisitions.

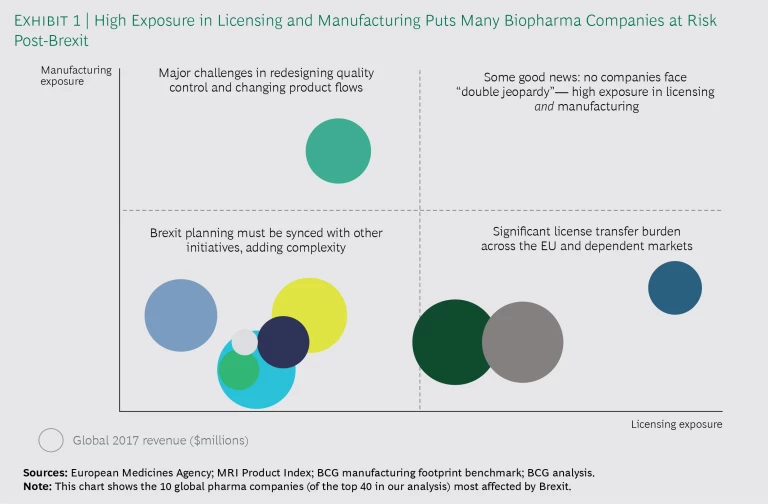

Biopharma companies are in various states of readiness for Brexit—understandable, given the prolonged uncertainty of the negotiations. But all feel the pressure to figure out how to prepare and what to prioritize. To understand the impact of a hard Brexit in two key areas for biopharma—licensing and manufacturing—we analyzed the top 40 global biopharmaceutical companies (by value). While we found that companies’ exposure in those areas varies considerably, all biopharma executives are being forced to make difficult strategic choices with limited guidance from policymakers. On the basis of our analysis and our work helping biopharma companies prepare for a new environment in Europe, we recommend some no-regrets moves that can mitigate risk in key areas.

Biopharma companies are in various states of readiness for Brexit. But all feel the pressure.

What Puts Companies at Risk

Our analysis assessed how biopharma companies would be affected by Brexit—specifically, the extent of the impact on licensing and manufacturing. Using public information and BCG’s manufacturing database, we determined the number of products in each company owned by a UK legal entity and the number of UK-based manufacturing sites. Exhibit 1 charts the exposure of the 10 companies (of the 40 in our analysis) most affected by Brexit.

Companies in our study have approximately 50 products on average (in more than one strength or dosage form) housed in legal entities in the UK. Companies with the highest exposure in licensing have more than 200. Because a single product can involve anywhere from 20 to 100 product licenses, this means that several thousand marketing authorizations (MAs) must be transferred to legal entities in the EU27 (the EU without the UK). In addition, companies must update their product packaging components and their licenses in certain downstream markets. Not only is this an administrative burden, but changes to licenses often trigger pricing and reimbursement discussions, which can affect revenue, particularly in the many markets experiencing pricing pressures.

The level of exposure in manufacturing depends on whether companies use the UK as a manufacturing center or as a conduit to wholesalers and distributors in the EU—or both. The companies in our study have anywhere from one to eight manufacturing sites in the UK. Even if Brexit affects just one site, more than 1,000 product licenses may be implicated. Before Brexit takes effect, companies will need to make multiple changes to their quality control testing and product flow to comply with EU importation requirements. This means updating or obtaining new manufacturing licenses, recruiting and onboarding new qualified persons (QPs), and transferring analytical methods for products originally licensed years ago. In the near term, biopharma companies with primary or secondary manufacturing sites in the UK will probably not move these sites to an EU country, but they may do so eventually in order to consolidate the supply chain.

Even if Brexit affects just one manufacturing site, more than 1,000 product licenses may be implicated.

Time Is Running Out

Some biopharma companies have held off with their preparations as long as possible in the hope of gaining more clarity on the likelihood of a transition period, which would give the UK more time to negotiate trade deals and companies more time to comply with regulations. But as the deadline approaches, and many details remain unclear, companies are left with no option but to plan for a hard Brexit.

As the deadline approaches, and as many details remain unclear, companies are left with no option but to plan for a hard Brexit.

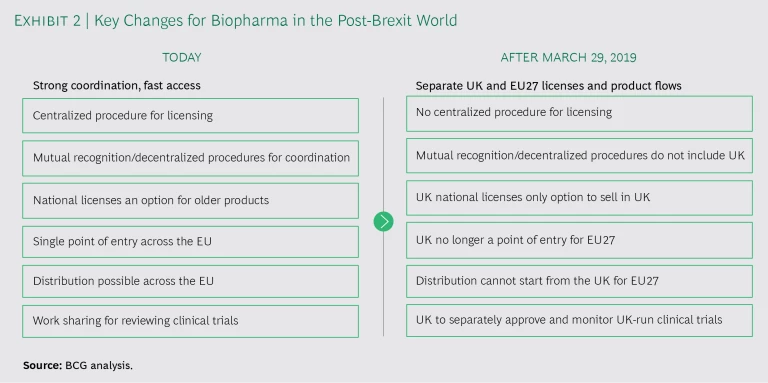

Biopharma companies will face changes in many areas post-Brexit. (See Exhibit 2.)

When companies scramble to file hundreds, if not thousands, of updates to their licenses and artwork, this, in turn, puts pressure on manufacturers and packaging sites to implement the changes in time for Brexit. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has indicated there will not be a grace period for production, which means new packaging must be ready before the Brexit deadline, and discussions are ongoing with the EMA on how packs with the old marketing authorization holder (MAH) details will be handled. To make matters more complicated, it’s not entirely clear whether EU and UK regulators are prepared to handle the administrative burdens associated with Brexit. (See “Will Government Services Be Ready?”.)

Will Government Services Be Ready?

Will Government Services Be Ready?

Biopharma companies are doing all it takes to submit their MA transfers and make changes to their product flow, but questions remain as to whether the EMA and other EU regulators have enough capacity on top of their normal workload to process these changes in a timely manner. Smaller EU regulators are already advising companies to submit their changes in waves, and it’s unclear if there’s adequate time for all transfers to get approved before March 29, 2019.

The MHRA still needs to publish guidelines on how it will handle licenses post-Brexit and whether it will accept EU-tested and released products for entry into the UK. In the meantime, companies will continue to submit licenses to the MHRA to ensure that products can reach patients in the UK. Like many, the MHRA is hoping for an arrangement where it can still work within the EU regulatory regime.

If a common market cannot be maintained, EU and UK customs services will also need to increase their capacity and develop processes for clearing products at the borders. Without timely clearances, there could be long delays for medicines in either direction, which could affect patients, particularly in cases involving time- and temperature-sensitive treatments. Biopharma companies and the government both want to maintain continuity of care and protect product quality. They also want to avoid panic buying by payers and providers ahead of a hard Brexit, which would put even more pressure on the system. Still, no formal guidance has been issued from any governments on how to prepare for potential stock issues post-Brexit.

Uncertainty Prevails

With less than a year to go until the UK exits the EU, there are almost daily updates on the negotiations. In principle, a transition period to December 31, 2020 has been endorsed by both the EU27 and the UK; however, it will need to be ratified with the complete Article 50 package, which means companies can’t count on it. Recent discussions have suggested that the UK could remain in the European Economic Area (EEA), an option that was previously considered off-limits. In that scenario, the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) could participate in EU regulatory procedures but would have limited ability to influence legislation. Biopharma companies, then, would need to make very few changes to their business practices.

Even as companies are spending millions to change their licenses and restructure product flow, it’s still possible the challenges around Brexit will largely go away. But even if they disappeared overnight, many companies would be too far along in their preparations to reverse course. In any event, given the unpredictable nature of the negotiations, it’s crucial for biopharma companies to invest in preparation.

Finally, there’s no clarity as to what type of mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) on good manufacturing practice (GMP) compliance and inspections may be put in place post-Brexit. And since MRAs often take years to negotiate bilaterally, it’s unlikely that any agreements will be set up before the deadline. In a hard Brexit scenario, agreements similar to those for Switzerland may be put in place to prevent the re-testing of products on entry to the EU27 or the UK. In a softer Brexit scenario, which would include some bilateral trade agreement, products would flow freely between the EU27 and the UK in the near term.

Are You Ready for Brexit?

In our work with biopharma companies to prepare for Brexit, we have identified critical success factors for meeting the rapidly approaching deadline. By taking action in these areas, companies can not only avoid disruptions but also unlock opportunities to strengthen their position in the industry.

- Understand where and how Brexit affects your business. Gain insight into how Brexit affects all of your product categories in the EU27, the UK, and associated dependent markets. Be clear on what needs to be implemented before Brexit and where current EMA guidance offers flexibility. A final version of the withdrawal agreement between the UK and the EU is expected to be drafted by October 2018; hold off until then on any changes that don’t need to be implemented before Brexit.

- Make Brexit preparations a cross-functional priority. Impart to leadership the importance of getting this right and the risks to patients if this isn’t executed on time. Set up a cross-functional supply chain and regulatory team to drive key initiatives.

- Develop an overarching, dynamic Brexit plan. Develop a holistic plan with cross-functional buy-in to address the impact of Brexit on all aspects of the business. Engage with teams that will be affected by Brexit and commit to developing solutions that address regulatory and supply chain constraints. Schedule at least one review after October, when guidelines should be clearer, to see if any initiatives can be dialed back or halted entirely.

- Agree on prioritization and track execution risks. Decide upfront which licenses, markets, and manufacturing sites to prioritize. Track any areas where it might be difficult to update licenses, change packaging, or move manufacturing sites, given tight timelines.

- Proactively engage with regulators. Engage with regulators, either through trade associations or directly, to access any Brexit-specific guidance and explore regulatory flexibilities, particularly related to patient care. Negotiate deadlines aggressively with regulators to protect the supply of medications. Regulators will be swamped with changes from biopharma companies, so don’t assume they can handle all of your regulatory submissions at once.

- Seize the opportunities in Brexit planning. Seek out the hidden opportunities that Brexit planning may present. For example, consider whether some of the tail end of your product portfolio should be discontinued given the impact of Brexit and the costs of ongoing regulatory maintenance. Furthermore, since product flows have to be adjusted, there may be opportunities to reduce the number of manufacturing sites, either in the UK or elsewhere, depending on the incentives the UK government puts in place. Take opportunities to renegotiate with payers on pricing. Share clinical outcomes data to demonstrate the value of your products and improve their position in the market, where appropriate.

Understandably, given the uncertainty, most biopharma companies have shifted into execution mode to prepare for a hard Brexit. However, we encourage biopharma to be bold in making suggestions to the UK government for how the country can become a more attractive marketplace for all stakeholders. For example, companies can advocate for mechanisms to achieve faster approvals, facilitate faster access, and support clinical research. It’s up to biopharma to identify opportunities to shape the UK and EU27 regulatory and access environments.