A roofing-tile manufacturer that launched a website to connect roofers and homeowners. A European manufacturer of building blocks, insulation, and other building materials that created a virtual companion for people interested in building their own homes. A home-heating-systems company that digitized the process of finding, buying, and installing a new furnace.

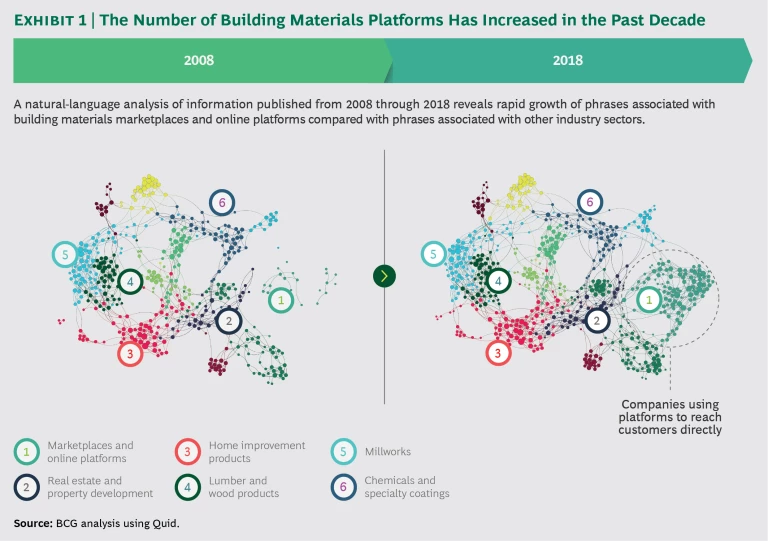

The companies—BMI Group, Xella, and Thermondo, respectively—inhabit three distinct segments of the light-side building materials manufacturing industry . Yet in one respect they have a lot in common. They operate in a world that is increasingly going digital. That change—along with increased competition and expanding opportunities—is motivating these companies and building materials manufacturers everywhere to rethink how they do business. More are looking to connect directly to end customers, building on the industry’s time-honored tradition of selling primarily to wholesalers and merchants. And they’re using online platforms and marketplaces to do it. In fact, our analysis shows rapid growth in the use of phrases associated with building materials platforms and online marketplaces compared with the overall industry, one indicator of the rising prominence of these forms of communication in the building materials business. (See Exhibit 1.)

Digitization is happening quickly, and building materials makers that don’t accept it and act accordingly will be left behind. Beyond their own desire to remain relevant and competitive, these companies also face a new threat as large e-commerce companies such as Amazon and Alibaba start to enter the market. Makers of drywall, bricks, and other commodity products could see their margins squeezed as a result of this new competition.

“It is too much of a risk to ignore this. You have to look to do something,” said Andrew Lawton, a longtime building industry executive and former managing director of Icopal, a UK-based roofing materials producer.

The growing number of building materials makers connecting with end customers online supports previous forecasts that successful companies in the industry would adopt digital technologies to go B2C, while middlemen would lose out as profits shift to platforms and online marketplaces. (See Bringing Digital Disruption to Building Materials , BCG Focus, November 2015.)

As shown by the three companies, there’s no single path that building materials producers should follow in their efforts to connect digitally with end customers. Regardless of which direction they choose, launching a customer-facing online presence brings multiple benefits. Companies gain direct access to customer information and feedback that they can use to better understand buyers’ motivations and needs. Such customer insights can help improve planning, product positioning, and pricing and can result in higher sales and profits. Finally, if done well, a digital venture can benefit the entire company by introducing it to innovative ways of thinking and working, and by bringing in people with new, digital skills.

The Challenges of Going B2C

Building materials producers must navigate multiple potential obstacles before they can realize the benefits of adding a B2C channel to their business. Until quite recently, building materials companies lagged behind those in other industries in adopting digitization. That’s partly a function of a mature industry with set ways of doing business. Few building materials makers had adopted B2C or digitization, so others were under no pressure to change and had relatively few formulas or role models to follow when doing so. Another reason the industry lagged behind is that homeowners and private builders have few occasions for buying building supplies for a remodel or new home compared with how often people shop at a store, listen to music, or visit a bank, for example. As a result, building materials producers have had far fewer opportunities to gather end-customer feedback that they could use to test and roll out digital services. In addition, the industry is regional and fragmented in nature, making it more difficult for companies to scale up a unified, end-customer-

focused operation.

For manufacturers accustomed to working with other businesses rather than consumers, the addition of B2C may require them to augment their existing capabilities in marketing, sales, and other operations so that they can effectively address a new customer base. Workforce-related obstacles may also hold up progress. Longtime employees accustomed to working a certain way may be hard-pressed to adopt new, agile, more consumer-oriented practices. Building materials producers typically lack sufficient workers with the needed skills for digital ventures, not just in web development but also in areas such as online-based sales, marketing, and customer service.

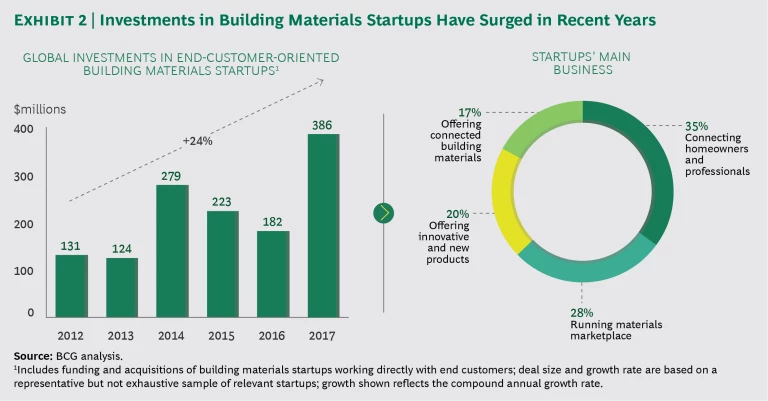

Given all that’s happening, building materials producers may want to rush into a B2C digital venture. But acting without a plan could jeopardize existing business and important relationships with distributors and contractors. Wrong-footed efforts also risk quelling a company’s willingness to continue experimenting to find its sweet spot in this space. By not acting quickly enough, though, a company could lose market share to emerging businesses, including B2C-focused building materials startups, which saw a surge of investments from 2012 through 2017. (See Exhibit 2.)

How Three Building Materials Makers Created an End-Customer-Focused Online Presence

The path that building materials manufacturers take to create a B2C initiative depends on their existing operations and vendor relationships, competition in their market segment, and whether they already have existing digital ventures or other online platforms. One thing that many of these companies have in common: they solve problems for end customers in their respective markets.

Create a website to connect end customers and service providers. For its initial digital venture, longtime German roofing materials producer Braas Monier (which changed its name to BMI Group after a June 2017 merger with Icopal) built an online platform to connect end customers with roofers. Originally, the company examined different options for entering the market. Given Braas Monier’s existing strong relationships in the industry, the company ultimately opted to use the site, called MeinDach (“My Roof” in English), to match roofers with homeowners looking for help. Homeowners can use MeinDach to manage the process of repairing or replacing a roof and get work done faster than they might have otherwise in a market where high demand and short supply result in waits of up to a year. The company uses the site to work closely with roofers to gain deeper insights into homeowners’ roof-buying habits that ultimately could bolster its own business.

Braas Monier was motivated to rework its business after executives visited California to learn more about digital initiatives. The company also wanted to preempt any attempts by digitally savvy startups to disrupt the roofing industry in the same way that fast-growing emerging businesses are disrupting other building materials industry segments.

Because Braas Monier sells primarily through distributors, the company needed to learn more about the problems that homeowners typically encounter when repairing or replacing a roof. The company conducted a large number of homeowner interviews to uncover roofing customer pain points and then came up with a concept for a site to solve them. It spent nine months on research, development, testing, and a pilot program with prequalified roofers in one small German market before launching the MeinDach site to the entire country in March 2017.

During and after the pilot, the company continued perfecting functions and adding features. It included a financing partner to offer customer loans and worked with makers of insulation, skylights, and other building materials that share information about their products on the platform. In addition, the company opened new sales channels and gained additional revenue by charging homeowners a service fee on the roofing projects, even when competitors’ products are used.

Braas Monier set up MeinDach as a separate brand and legal entity to develop ideas and work faster than if it had been part of the overall company, and that independence paid off. In the first 12 months, MeinDach supported the sale of roofs to more than 100 homeowners, about five times the yearly average for a typical German roofer. As the site gained traction, the number of roofers interested in partnering with Braas Monier jumped considerably, from 12 to more than 500, aided in part by the sales team, which used existing contacts to encourage roofers to partner with the company.

During the same time, the company’s customer acquisition costs—expenses related to promoting the service and converting shoppers into buyers—dropped from several hundred euros per homeowner to approximately 20. Part of the decrease came from bringing customer service in-house, which gave the company more control over costs and service. Encouraged by its early success, Braas Monier plans to add other new services and expand MeinDach to additional countries where it operates.

Offer a free platform to build traffic and generate leads. For Xella’s first B2C digital initiative, the European wall-building materials producer created a free virtual companion for private homebuilders to drive traffic and awareness and eventually sell products directly to consumers.

Xella created the Building Companion website as an online project management center for people interested in remodeling or building their own homes. Xella chose to launch Building Companion in Poland, a market ripe for digital disruption because of end customers’ existing preferences. It’s common for Polish homeowners to act as their own general contractors for new home projects, and the internet is their go-to source for information. More than 50% of prospective homeowners buy home blueprints online. But few comprehensive guides existed that explained the steps involved in the homebuilding process, and no central database of contact information for contractors and subcontractors was available.

Xella looked to change that with Building Companion, which is available as both a website and a mobile app. Homeowners can use either one to find an architect or contractor precertified by the company from a database of industry professionals that Xella built over the years. They can also use it to buy building materials, including materials from Xella and other companies, that are delivered by local dealers. The site includes a virtual construction schedule with a step-by-step guide that leads private homebuilders through each stage of construction and adds tasks to the calendar on their phone. It also lets users upload photos of projects in progress and share an account with a spouse or partner.

Xella spent most of 2017 planning and building the site, including working on the initial concept to determine what features to offer and developing the platform, and launched the site late in the year. To build traffic and gain sales leads, Xella offers discounts to homeowners who share personal information—for example, a voucher for a discount on a pallet of building blocks—in exchange for completing the first two steps of a ten-step process to register on the site.

So far, the company’s strategy is paying off. In the first four months that it was available, Building Companion grew to working with more than 60 architects, 30 contractors, and 50 merchants in the region of Poland where it was initially available and registered a steady increase in traffic to the site. The company is expanding the platform to cover other parts of Poland and expects to introduce the service in Eastern Europe and other areas where it does business. Once Building Companion has sufficient traffic, Xella may consider offering additional paid services. The company may also charge fees to service providers such as architects in exchange for providing high-quality leads or to other building materials makers that want to market their products on the platform.

Go digital to offer products and installation. Not all consumer-facing building materials digital ventures evolved from a longtime producer’s existing business. One that has had success as a startup is Thermondo, the venture-backed home-heating-systems service business. Started in 2012, Thermondo has captured a substantial share of the German market and, according to its own estimates, is that country’s largest certified home-heating-systems installer. By offering a level of professionalism that had previously been missing in that market niche, Thermondo has become an established force in the segment, one whose advances other companies now follow.

Before Thermondo launched its online-based service, the heating-systems business was run primarily by individual installers who oversaw the entire process, from getting estimates to managing paperwork. Homeowners could expect to spend up to eight weeks choosing a home-heating contractor and waiting for an estimate and from several days to several weeks for installation. Final costs often deviated from estimates by up to 20% for a variety of reasons, including unforeseen circumstances at the construction site and the fact that many contractors do not specialize in home-heating systems.

Initially, Thermondo built a digital service to connect homeowners with heating-system installers. The business model proved difficult to scale, however, primarily because the company lacked control over the quality of the work being performed. In response, the company pivoted to hiring its own workforce.

Thermondo also developed a proprietary computer algorithm to analyze information that homeowners input on the website about their heating-system needs. The program combines that data with data from more than 10,000 previous installations to generate a fixed price for the requested system in a matter of minutes. In addition to its efforts to improve pricing accuracy, Thermondo increased efficiency by hiring separate personnel for installation work and administrative functions, upgrades that helped cut wait times for installation to a matter of days.

The company experimented with marketing strategies to promote the service, including radio, but ultimately focused on online marketing. To make customers more comfortable with making such an expensive purchase online, the company follows up a customer’s initial online transaction with a phone call and onsite visit.

By early 2018, Thermondo was installing 300 to 400 home-heating systems a month. Thermondo continues to evolve its business model. In 2017, the company launched a heating-as-a-service offering called Thermondo 365, which is coordinated through its website and has already grown to account for approximately 30% of its business. Instead of buying equipment outright, customers contract to rent it for ten years, creating a long-term relationship that gives the company more opportunities to sell related services. In addition, the company has started selling heating systems to business customers.

Implementing a B2C Building Materials Online Presence

To fully embrace a B2C digital venture, building materials producers must think of themselves as sellers of services, not products. “We have to sell solutions to problems,” said Xella CEO Jochen Fabritius.

Creating a solutions-focused B2C online platform starts with uncovering customer pain points and weighing options for solving them and then incubating the best option into a viable service. It then moves on to commercializing the venture by rolling it out to the public, expanding what’s offered, and course-correcting as needed. (See Exhibit 3.) Building materials producers that are already operating digital initiatives may be tempted to skip the early steps, but it’s critical to go through all of them to make sure that assumptions are sound, end-customers’ pain points are understood in depth, and digital solutions actually address these unmet needs.

Innovate. Because so many building materials producers have limited experience working directly with end customers, understanding customer pain points is a significant hurdle to creating an online B2C presence. In addition, companies may not be familiar with digital services or products that could address those concerns and may not know what their internal capabilities and financial resources are for offering them.

Conducting ethnographic interviews is one way to uncover end customers’ concerns. When Braas Monier began to work on what eventually became MeinDach, the company conducted this specialized type of interview to understand the problems that homeowners encounter when looking for information on roof repairs and renovations. Interviewers visited people in their homes, posing open-ended questions about roofing-related experiences and observing body language to pick up nonverbal cues. The company conducted similar interviews with roofers. Through the research, Braas Monier discovered that both homeowners and roofers found the roof renovation process to be consistently inefficient and frustrating. The feedback helped the company identify different ways to address the problem and translate them into a roadmap for the type of services to offer.

It’s not unusual for interviews and other research to uncover multiple pain points that companies then need to prioritize according to which are most common or serious, which are easiest to solve, or which offer the most promise for changing habits. After prioritizing pain points, companies should develop high-level solutions to the most pressing problems. An interdisciplinary project team can review a handful of options in more detail to consider if potential users need the service, what functions to include, and whether those functions are technically possible to deliver, as well as to evaluate potential revenue and development costs. As part of this phase, companies can also inventory existing internal projects to determine if any could address these problems.

When evaluating possible solutions, companies shouldn’t neglect to take into account what’s already in the market. If two or three services just like what they’re considering already exist in the same industry niche, it could signal either late or great market timing. The deciding factor will be whether a new entrant would bring any advantage with it, such as superior insights into the market or the ability to build on the existing assets of a parent company that would give it a competitive edge.

To pick a solution for development, some companies hold a “shark tank” session—named after the US TV show—where the project team and members of the management team evaluate and refine ideas on the basis of their potential and eliminate weaker choices until only the strongest concepts survive and move to the next phase.

Incubate. Converting a concept for a B2C online presence into a concrete service starts with creating a minimum viable product (MVP). For building materials producers, this bare-bones prototype could be a B2C online platform or e-commerce site built relatively quickly with limited functions and tested on a small group of friends, family members, or employees to collect initial feedback. That feedback could be used to build a more user-friendly interface and additional functions before introducing a pilot to a small customer group for further testing.

In instances where existing personnel may not have much experience with MVPs and B2C initiatives, companies may consult with outside advisors. Or they may even bring in an external manager to temporarily lead a project before turning it over to internal managers once those team members gain the needed skills.

Some companies launch a digital service under a different name to create a new, more modern image. Xella debated launching its B2C platform under its own brand but ultimately opted to use a different name, logo, and color scheme to distinguish it from the company’s existing business. Visitors to the site see Xella product brand names throughout the site and on the app, however.

Part of incubating a digital initiative is experimenting and refining processes on the basis of feedback from initial users. In some cases, this could involve A/B testing or testing different options on different groups to see which works best. Other features could be tested on all users. Not all experiments are successful. Braas Monier added a Google maps feature to MeinDach to show homeowners an image of their home’s roof to better estimate the size, a required step in the site’s registration process. The feature failed to slow registration drop-offs, however, and the company abandoned it. Registrations improved after the process was redesigned so that homeowners had to choose between only three roof size options (small, medium, and large), and the company continues to refine the process.

Commercialize. An online platform or marketplace is ready for a public launch once two things have happened. The company must have strong evidence that the new product or service it has developed fits the market, and decision makers need to have secured the necessary resources to support a fast rollout.

If the product or service has been designed well, it should immediately begin generating data that leadership can use to make decisions—for example, about how fast to grow supply given the market demand—rather than relying on estimates and guesses.

Once a service is live, determining how best to build it out and deciding which opportunities to pursue will be continual challenges. Looking at the original goals for the service as well as what motivates end-customer adoption should help companies decide whether to add features, expand into new territories and market segments, or bring on partners that might be interested in offering complementary services.

For a fledgling commercial venture, the goal is not to aim for a quick breakeven in the first year or two but rather to continue improving the user experience to generate traffic and attract more potential customers.

Pivots are part of the process. Changing direction isn’t a sign of failure but signals that a company is redirecting its efforts to aspects of a digital B2C venture that are working. Thermondo started out thinking it would use a B2C platform to generate leads for heating systems. But the company quickly learned that installing heating systems is difficult and decided that, to offer good customer service, it needed to manage its own contractors. Because home-heating systems in Germany can cost €6,000 to €8,000, the company also added phone and onsite consultations to address any concerns homeowners might have about buying something so expensive online.

Other Lessons Learned

Taking a customer-first approach may be a 180-degree switch for building materials manufacturers that may traditionally have developed new products or services on the basis of their existing products and capabilities. From our work helping to guide building materials industry clients through this journey, we have learned some broader lessons that can help to prepare a new venture for success.

Involve existing business partners early in the process. While it’s important to cultivate direct relationships with end customers, don’t neglect traditional business partners, whose resources can make them valuable allies. Communicate about B2C projects early so that partners are aware of what’s happening. To avoid potential backlash, explain the threat that new forms of competition pose and discuss options for working together to address that threat.

Don’t expect a B2C venture to take off overnight. Although designing and building an online B2C platform may take only months for a company to plan and launch, it may take considerably longer for a new venture to gain momentum. Be patient.

Expect changes to traditional sales channels. Established companies launching digital ventures may see the results reflected in their established, offline sales channels as some of that business shifts online. But even if some sales come in through a new channel instead of the old one, they still benefit the same corporate parent. Ultimately, the presence of a second channel could expand overall sales.

Capitalize on corporate assets to create an advantage in the marketplace. If a venture’s parent company is an established entity that consumers recognize, emphasizing the connection can help the venture rise above smaller, less well-positioned startups. Corporate assets that a new digital venture could capitalize on include brand names, access to stakeholders such as wholesalers and distributors, products, and industry contacts. The MeinDach team capitalized on Braas Monier’s longstanding relationships with roofers by approaching them to work together on the online platform. This gave the company a clear advantage over startups and e-commerce giants eyeing the market.

Separate digital ventures from established operations. Allowing teams that are running digital initiatives to work with limited connections to existing corporate infrastructure gives them the autonomy to experiment. That could extend as far as operating from a different location. Digital innovation teams need to design and test prototypes quickly to see what works and what doesn’t. That’s hard to do if teams are embedded in existing operations where following departmental protocols could add complexity and slow down the process. For example, testing new software could take weeks or months inside a corporate IT department because of the need to follow security measures but only a few hours inside a digital-venture incubator. Keeping B2C initiatives separate also makes it easier for a team to test management styles and resources that, if successful, could be introduced to the entire corporation and inspire larger culture changes.

The building materials industry is as grounded in tradition as a house is bolted to its foundation. But changing consumer preferences and fast-paced competition are pushing companies to loosen those connections in order to add services that appeal directly to end customers—and they are using digitization to do it. For organizations that have never launched a digital venture, the prospect may feel overwhelming. The key is to start small, breaking the process into incremental steps to pinpoint customers’ problems and the best way to solve them, and then create a digital venture to deliver the solution. Startups may be able to do that faster. But established organizations can draw on existing brand awareness in the marketplace and longstanding relationships with business partners to buoy their efforts. That’s a business to build on.