In a December 2017 interview, Volkswagen CEO Matthias Müller suggested that it is time to replace subsidies for diesel with incentives that support electric vehicles.

“I’ve become convinced that we should question the sense and purpose of the diesel subsidies,” Müller told Handelsblatt. “If the switch to environmentally friendly e-cars is to succeed, diesel combustion engines can’t continue to be subsidized the way they have been forever.”

These words from a major diesel producer sparked a debate in the EU, where nearly half of all new cars sold run on diesel. This move could well trigger a transformational shift in the transportation industry.

The Volkswagen story is an example of corporate statesmanship. We believe that there is now a strong case for CEOs to take a bolder role in addressing some of society’s major issues.

What Is Corporate Statesmanship?

In politics, statesmanship refers to the skill of managing state affairs; a statesman, according to Merriam-Webster, is “a wise, skillful, and respected political leader.” Statesmen place the common good above their own interests and actively work to shape the context.

Because they control wealth, the fate of employees, and the products they market, CEOs are influential political players, whether or not they realize or exercise their power. They can therefore realistically aspire to statesmanship by acting for the common good and not just the immediate interests of their companies.

CEOs are influential political players, whether or not they realize or exercise their power.

We can define corporate statesmanship as the action of a company, and in particular of its CEO, to intervene in public affairs to foster collective action in support of the common good beyond the scope of his or her enlightened self-interest.

Society Faces Unprecedented Challenges

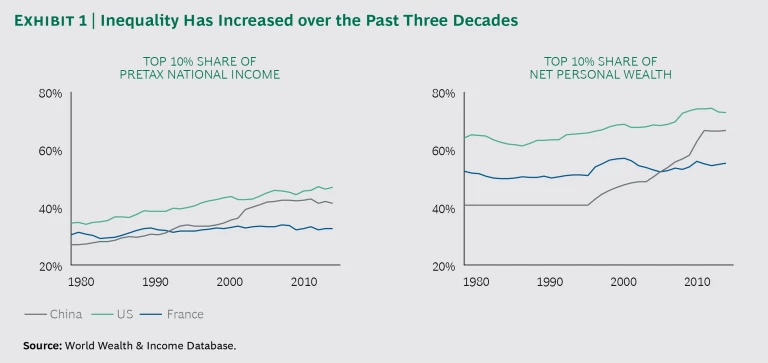

Social stresses abound, and 2018 may well prove to be a moment of truth for CEOs , especially in the US, where companies will be under greater scrutiny because of tax reductions and regulatory relief. The societal challenges we face are well known. Inequalities have been strongly increasing over the past three decades, although more slowly in Europe than in the rest of the world. (See Exhibit 1.) The rise of a new protectionism is part of a backlash against globalization that is starting to impact business itself. The capacity of technology to foster progress and economic development is being questioned. The development of AI and robotization is increasingly feared as threats to employment rather than seen as drivers of opportunity.

Another major challenge is the declining ability of the public sector to protect public goods, and in particular the environment. The latest research shows that despite the technologies at our disposal, we will likely miss the targets of the Paris climate accord. And a growing world population will place further stress on the environment: irreversible biodiversity losses, water scarcity, lack of arable land, and pressure on protected areas all seem likely to intensify.

Traditionally, we would expect governments to address these issues. In most of the world, there is a historic division of roles: corporations drive economic activity while governments take care of the common good.

As a result, there is an understandable reluctance for firms to get involved in public affairs. And giving companies a larger role can certainly create conflicts of interest, akin to having the fox watch the hen house. Numerous historical cases of failures of self-regulation support this view. Alan Greenspan, the former chairman of the Federal Reserve, famously claimed, “I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interest of organizations was such that they were best capable of protecting their own shareholders.”

Governments Won’t Necessarily Be Able to Address the Challenges

There are good reasons to believe that governments may not be in a position to address some of today’s challenges by themselves.

The scope and scale of some of the challenges are arguably too broad even for large countries, while weakening global cooperation reduces the chances for collective action. Political cycles limit the ability of governments to address long-term issues. On average, there are 1.7 national elections every quarter in the EU , undermining the continuity needed to attack long-term challenges. And increasing political polarization further limits opportunities for public action in many parts of the world.

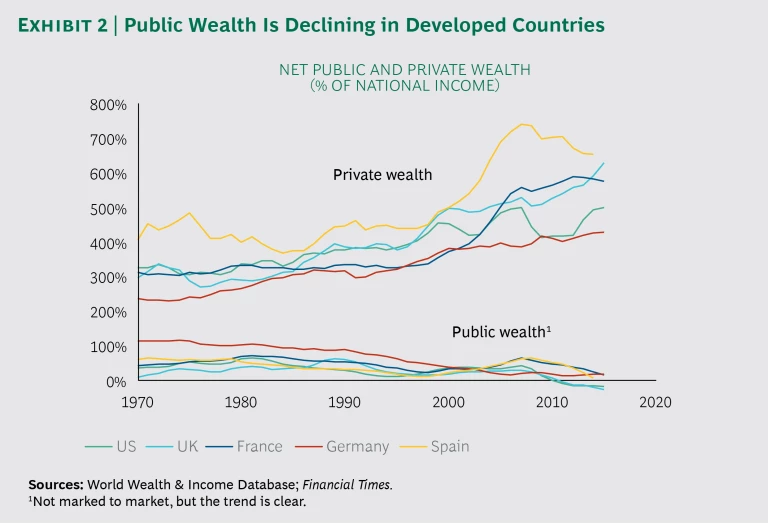

Financial pressures also contribute to institutional fragility and constrain public action. The welfare state is reaching its limits in developed countries, driven by an aging population and a shift from public wealth to private capital. (See Exhibit 2.)

The picture becomes even more complex if we consider the compounded effect of these challenges. For instance, 2015 research demonstrates the statistically significant effect of income inequality on political polarization.

As a result of these and other factors, confidence in governmental institutions is falling, which further reduces the power of states as change agents. According to the Pew Research Center , public trust in the government is near historic lows in the US. Only 18% of Americans today say they can trust the government to “do what is right.”

The Case for Stepping Up

Given this, there is a strong case for corporations to step up their statesmanship.

Of course, many CEOs fear that a more public role might expose them to backlash, especially in a context of increasing skepticism toward institutions. In a recent survey , while 38% responded that CEOs have a responsibility to speak out on controversial issues, 36% said they believe the top reason for CEO activism is “to get media attention.”

Many CEOs fear that a more public role might expose them to backlash.

As in postwar Japan, corporations are economic giants but still political dwarfs. Leaders tend to focus on immediate business problems: a 2017 survey by the National Association of Corporate Directors showed that only 2% of board directors see the role of business in society as having the greatest effect on their company over the next 12 months.

However, the risk of acting needs to be balanced against the risk of inaction. If companies remain passive , they could soon find themselves damaged by an environment of escalating political risk. Ultimately, consumers and society have the power to sanction or restrict the freedom of action of global corporations. Regardless of political inclinations, corporate leaders have a common interest in preserving the game of business and defending the drivers of growth, like technology and globalization.

If companies remain passive, they could soon find themselves damaged by an environment of escalating political risk.

Corporations don’t just have a self-interest to step up—they are also well positioned to do so. Fundamentally, they are effective at problem solving. They can act globally, in contrast to national governments. They have access to resources, skills, and technology. Profits and cash accumulation are at historical highs, especially in the United States, in light of recent corporate tax reform, so there is a large margin for action right now. As the influence of business has grown, so has its ability to shape the provision of the public goods that are essential for market stability.

Ultimately, business cannot succeed if societies fail. Global markets need global rules for business to play its proper role in creating wealth and spreading solutions.

Statesmanship Is More Than CR

The business community is increasingly stepping up on sustainability and corporate responsibility (CR), not least because of growing evidence of a positive link with financial performance. The recent ascendancy of sustainable investing, enabled with tools such as the Arabesque S-Ray, will further accelerate good practices across industries. This alignment of finance with CR could make a significant contribution to society in terms of environmental stewardship, workplace conditions, and good governance.

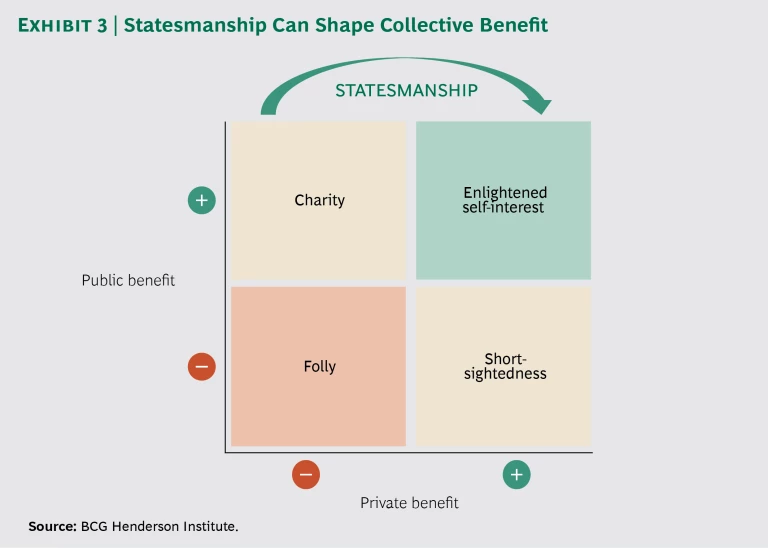

In essence, CR is a long-term maximization of self-interest in which companies ensure that they don’t damage themselves by undermining their own environments. CR is fundamentally about individual action, in ways that are compatible with common interest—in other words, “doing well by doing good” within an existing policy framework.

Statesmanship, by contrast, goes a step further. It is about shaping the policy framework to advance the public and private interests and changing the game by influencing the collective will. (See Exhibit 3.) It tackles problems that can’t be resolved through the enlightened self-interest of individual companies. In economics, the prisoner’s dilemma describes situations in which without collective action all actors tend to undermine one another, which leads to suboptimal individual outcomes. In other words, because each company follows its own path, an entire industry or economy ends up hurting itself. In those cases, statesmen are needed to foster cooperation and lift everyone to a better equilibrium by changing the nature of the game.

Cybersecurity is a good example of a prisoner’s dilemma in business. Everybody has a direct interest in protecting their data: citizens, consumers, and producers alike. But nobody has an interest in investing too much in the security of their own systems. This leads to systemic vulnerability, where breaches of security could have a negative impact on all and take down companies.

The Path to Statesmanship

First, Be a Good Citizen

A good statesman must be a good citizen. Gaining trust requires behaving responsibly and being perceived in this light by other stakeholders. Maximization of total shareholder return (TSR) within legal boundaries is not enough. Leaders need to define clearly a human purpose , the higher social goal their corporation serves, and ensure that their impact is compatible with that purpose. And they need to ensure that their own operations are based on values and a commitment to integrity.

A good start is the assessment of your firm’s economic, social, environmental, and political impact. To this end, companies can think in terms of their total societal impact (TSI) , a collection of measures and assessments that can be used to lay the foundations for a sound sustainability strategy.

Understand and Protect the Rules of the Game

Above being a good citizen, statesmen need to protect the rules and institutions that guarantee balance in society. Companies benefit from a “license to operate” from society. Statesmen understand the underlying conditions of the game and the lines that cannot be crossed without jeopardizing that license.

Consider Allergan CEO Brent Saunders. “The health care industry has had a long-standing unwritten social contract with patients, physicians, policy makers and the public at large,” he wrote in a company blog. The perceived breach of that contract could threaten the entire industry. “As the focus on price has heated up,” he noted, “the innovation ecosystem has come under assault, and it is fragile.”

To protect the game, Allergan offered a new “social contract” to patients, with a focus on responsible pricing. The company then argued for industry-wide action, along with other CEOs. Recent data suggests Allergan’s commitment on pricing may be shaping industry norms.

Bolster Government

To play the game of business, companies need a fair set of rules and a referee. We tend to forget the value of regulation and criticize overregulation, but the rule of law is a basic condition for economic development. In Africa, fintech CEOs have been calling for regulatory action to prevent fraud and facilitate the development of the industry. As SimbaPay CEO Nyasinga Onyancha has noted, “Regulations have a huge role to play in ensuring the fintech industry becomes bigger and better.”

In developed economies, too, companies should support the role of the state as regulator and referee. Elon Musk’s letter calling for the banning of autonomous weapons, which select and engage targets without human intervention, is an example of embracing regulation for social good. As the letter states, this about protecting the game and preventing “a major public backlash against AI that curtails its future societal benefits.”

Support Smart Regulation

Empowering governments is a first step, but corporate leaders also need to propose and support smart regulations to preserve social balance. A case in point is the financial industry, which is highly complex and interconnected. It shares many features with biological systems , in which all actors benefit from the ecosystem. In such situations, actors that overstretch the system by systematically maximizing their private benefits may provoke its collapse.

Because statesmen are aware of those dynamics, they assume a wider responsibility and support regulations that underpin a sustainable future for their industry. ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods realizes that “growing demand creates a dual challenge: providing energy to meet people’s needs while managing the risks of climate change.” Therefore, in his first blog post as CEO, he advocated a “uniform price of carbon applied consistently across the economy” as the smartest way to meet that dual challenge.

Oppose Injustice

When confronted with situations that are obviously unfair, the statesman takes action. As Elie Wiesel put it, “We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim.” Assessments of “right” and “wrong” should be informed by universal values and principles that we have learned from history.

According to the framework developed by economist Albert O. Hirschman, there are three ways to act: Exit (refraining from participating in markets that don’t meet certain standards), Voice (protesting publicly), and Loyalty (silently approving where general interest prevails, but the silence is chosen rather than by default; the decision can be explained later if necessary).

“Voice” may generate unwanted exposure for a corporation. One option for CEOs to mitigate such a risk is to distinguish their opinions as citizens from those of their companies. Sergey Brin attended demonstrations in his personal capacity, not as the president of Google. This can be a good way to respond without the company appearing to customers and stakeholders as politically biased.

Take the Lead

The major issues of society are well known. Sometimes even the solutions are obvious, but political, social, or economic conditions prevent those solutions from being implemented. Statesmen do not use this as an excuse and instead take the lead and demonstrate that action is possible.

In the cybersecurity example above, Google built a group of hackers called Project Zero in order to identify and address digital threats, with a focus on the software made by other companies. This is a tangible way for Google to show that it takes responsibility for the overall stability of the system.

Shape and Join Horizontal Coalitions with Other Companies

Taking the lead is meant to trigger collective action. For businesses, the rationale for engaging with others is not just about maximizing impact. Acting with other industry players is also a way to ensure that the conditions of competition remain fair and equivalent for all.

CEOs can help form and shape such coalitions to realize their values. There are many ways to do this, but the UN Global Compact has been decisive in providing a unified framework for business coalitions across a wide array of sustainability principles based on universal values.

In a particularly striking example, more than 400 companies, including Microsoft, Adidas, and Sony, have committed to being climate neutral —that is, to minimizing their greenhouse gas emissions and compensating for unavoidable emissions. Businesses should not be afraid to engage with other types of actors too: the climate coalition also includes individuals, cities, and nonprofits.

Shape Vertical Coalitions with Investors

CEOs have a direct legal responsibility to their shareholders. Business leaders often use this as an argument for remaining within the strict limits of their assumed mandates and focusing on the maximization of TSR. However, there are now many examples of investors pressuring leaders to take a stand on societal issues. In January 2018, two Apple investors pressured the company to address concerns over smartphone addiction. They requested that management better assess the mental health effects on children and take appropriate action.

Neglecting this type of pressure might come at a high price. Norway’s pension fund, the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, which owns on average 1.3% of every single listed company on earth, decided to divest from oil and gas as part of a climate change strategy.

Neglecting pressure from investors might come at a high price.

Sustainable investing enabled by technology and big data analysis, as advanced by firms like Arabesque, is turning investors into increasingly powerful allies for corporate statesmen in addressing social challenges.

Build Narratives

It is often impossible for even informed citizens to know all the facts, which are in any case often disputed, especially in the case of controversial social issues. People understand reality individually and collectively through stories. Statesmen exert influence and shape minds and foster action through narratives. CEOs need to explain why they believe what they believe and advocate for it by building understandable and compelling narratives, which not only stand up to scrutiny but can create alignment and support.

Lyft cofounder John Zimmer is well aware of a risk of backlash against new forms of mobility. So he argues that car sharing is more than a business—it has a huge impact on the design of cities. As he wrote on Medium, it has “tremendous implications on global economics, health, social equality, the environment, and overall quality of life.” This puts the company in a better position to shape the future of the industry.

Business leaders need to face the inconvenient truth that some aspects of collective welfare can’t come from individual maximization efforts, even enlightened ones. They require the “technology of leadership” to solve the prisoner’s dilemma of noncooperation leading to poorer outcomes for all.

Corporations that lead will be trusted more and accepted as partners by governments and citizens. Actions will foster more actions, and 2018 could well be a foundational year for corporate statesmanship.