In the past decade, it has become commonplace to see companies launch a transformation—a comprehensive change in strategy, operating model, organization, people, or processes. Our research finds, though, that many transformations do not create shareholder value. Indeed, among recently launched transformations, only one in four has succeeded in creating shareholder value above the industry average.

On the basis of our experience working with firms across industries, we believe CFOs have a vital role to play in helping companies establish and achieve a transformation’s objectives for value creation. Today’s CFOs are expanding their roles beyond traditional financial-reporting responsibilities to become proactive custodians of shareholder value. In this expanded role, CFOs promote value creation by serving as strategic advisors to business leaders, overseeing performance across the organization, and communicating a persuasive equity story to investors.

The greater scope of responsibilities makes CFOs uniquely well positioned to understand the sources of value, set fact-based improvement targets, optimize resource allocation, and ensure accountability for results. To maintain a relentless focus on value creation, CFOs must play an important role in each phase of a transformation

Why Transformations Need an Activist CFO

The need for an activist CFO has become clear as companies increasingly consider transformations to be an essential part of their efforts to adapt to fast-changing markets and outperform their peers. According to a BCG analysis, 52% of large public companies in Europe and North America announced transformations in 2016, a 42% increase compared with 2006.

Moreover, many of these companies are launching transformations in rapid succession: 73% announced two rounds of cost restructuring combined with reorganization or downsizing within two years. Implementing transformations and evaluating the return on investment has become increasingly complex, however. For example, three-quarters of the companies we studied are investing in digital technology, a field in which they are still building the operational and financial expertise required to develop a business case for investments.

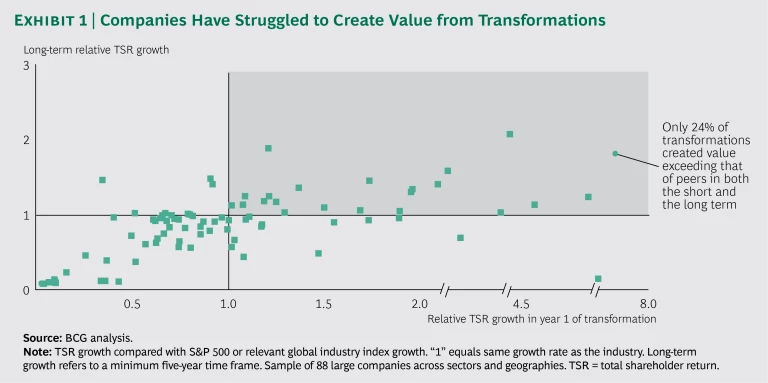

To assess whether transformations are creating value, we compared the growth of the total shareholder return (TSR) of transforming companies with that of their respective industry. (See Exhibit 1.) Only 24% of transforming companies experienced greater TSR growth than their industries over both the short term (one year) and the long term (five or more years). (TSR is the annual percentage return to owners, which comes from capital gains plus any dividends. In this analysis, we compared TSR growth with that of the S&P 500 or a relevant industry index.)

BCG research has also found that value creation is highly correlated with margin expansion. We analyzed the sources of value creation for a sample of more than 700 large public companies in Europe and North America from 2011 through 2016. The main differentiator between first-quartile and second-quartile TSR performance was margin change, followed by sales growth, multiple change, and dividend yield. The best performers recognize that margin growth not only contributes directly to TSR but also generates cash to invest in growth opportunities and pay dividends. For many companies, operational-improvement initiatives aimed at reducing the cost base are the most effective way to increase margins.

Understanding the sources of value creation is only the starting point. Companies must translate this knowledge into effective initiatives and allocate the appropriate resources. They also need to define metrics for tracking and evaluating the impact of these changes from the perspective of value creation. And they must ensure that investors understand how the transformation will boost the company’s TSR.

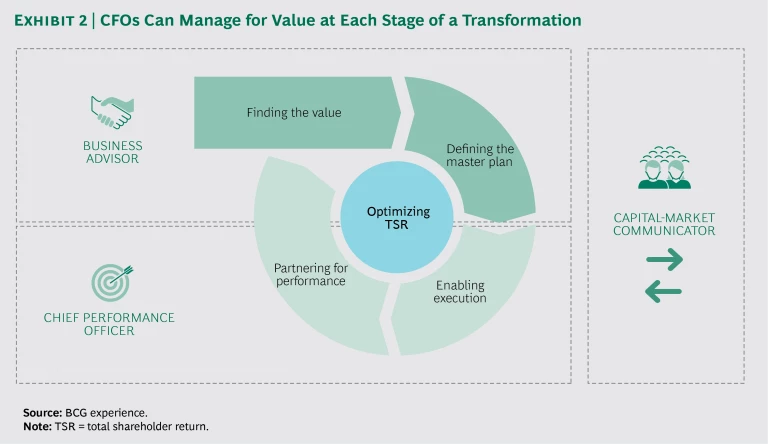

Fortunately, today’s CFO is in a unique position to address such issues by supporting transformations on three essential fronts:

- As the only impartial business advisor, the CFO can use the lens of value creation to challenge the effectiveness of the current operating model and shape priorities for a target operating model.

- As the chief performance officer, the CFO can define KPIs that promote the value creation priorities and then proactively manage performance and enforce consequences to achieve the desired objectives.

- As the company’s primary capital-market communicator, the CFO can convey a clear value creation story to the investment community, drawing an explicit connection between the company’s improvement initiatives and TSR.

CFOs’ new leadership role in corporate transformations, especially those that fo-cus on operational improvements, is a further advance in the development of their responsibilities from backward-looking reporting to forward-looking strategic support. To help CFOs address the challenges of action-oriented performance management, we offer guidance on how to ensure that transformations produce value.

Managing Transformations for Value

To optimize TSR, CFOs should play a role in all four phases of a transformation (see Exhibit 2):

- Finding the value

- Defining the master plan

- Enabling execution

- Partnering for performance

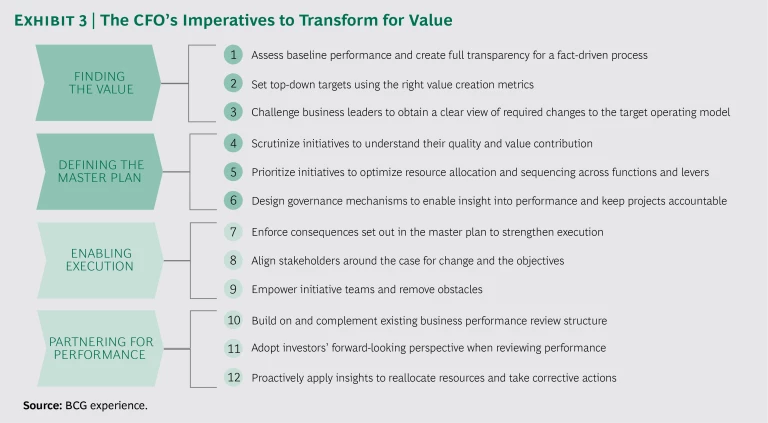

CFOs’ actions across these four phases can be distilled into a set of imperatives to transform for value. (See Exhibit 3.)

Finding the Value. In the first phase, the CFO identifies the sources of value creation and establishes improvement objectives. This entails clarifying the baseline performance, determining the right metrics for assessing value creation, and setting top-down targets. By challenging business line leaders about value creation opportunities, the CFO helps the company develop a value-oriented vision for its target operating model.

Recently, a global telecom company launched a large-scale cost improvement program in response to slowing growth. To provide a fact base, the CFO conducted a systematic appraisal of baseline performance. The assessment took into account the development of costs over time as well as the maturity of existing improvement initiatives and their potential impact. By providing a better understanding of the status quo and improvement priorities, the results enabled the CFO to set clear top-down targets. These targets not only helped to shift the mindset of company leaders but also enabled the business lines to discuss more aggressive, transformative changes. Furthermore, the assessment results helped the CFO explain the transformation’s objectives to investors during the company’s Capital Markets Day event.

Defining the Master Plan. The master plan sets out the transformation’s initiatives as well as their sequencing and resource requirements. To support the plan’s development, the CFO assesses the quality of proposed initiatives and their contribution to value creation. In addition, the CFO designs the governance for the transformation, aiming to provide insight into the development and maturity of projects and promote accountability.

In defining the master plan for a global industrial company’s transformation, the CFO collaborated with the CEO to prioritize 50 improvement topics. They organized the topics into approximately ten work streams and then sequenced the work streams so that those enabling other improvements were undertaken first, followed by the highest-impact initiatives. To facilitate frequent performance reviews and rapid course corrections, the company implemented a governance structure that enabled the CEO, the CFO, and the chief human resources officer to actively manage the improvement portfolio.

Enabling Execution. In the role of chief performance officer, the CFO ensures a successful transition from the definition of the master plan to the execution of it. To encourage the business lines’ adherence to the planned initiatives and resource allocation, the CFO enforces the consequences (such as loss of funding or staffing) that stakeholders agreed to in the plan and aligns stakeholders around the case for change as well as the transformation’s objectives. To promote progress and a sense of ownership, the CFO empowers project teams and supports them in resolving issues, making decisions, and removing obstacles.

In one instance, the CFO of a US retail chain determined that the company would need to improve its margins in order to continue enjoying profitable growth. However, a significant mindset shift would be required to motivate the organization to pursue margin-improving initiatives: executives and employees were proud of the company’s historically strong performance, and benchmarks still indicated relatively low costs. Recognizing the challenge, the CFO framed a case for change to convince the organization that cost reduction was necessary to maintain the current rates of growth and profitability over the long term. The CFO also fostered stakeholder alignment—first by working closely with the executive team and top management and then by communicating the case for change and the improvement initiatives to the broader organization.

Partnering for Performance. By building on the existing review structure, the CFO ensures a strong connection between the transformation and ongoing business performance and avoids creating an additional layer of performance management. To help teams manage performance, the CFO selectively adds milestone-oriented KPIs to the review structure, ensuring transparency into achievement of the initiatives. The CFO adopts the forward-looking perspective taken by investors and proactively applies insights to reallocate resources and take corrective actions.

At a financial services company, the CFO supported business leaders in conducting hands-on performance reviews in which they took a forward-looking perspective on the potential benefits of a transformation they were undertaking. The reviews set clear expectations regarding the corrective actions that would be taken if progress fell short of targets. Although the CFO gave leaders latitude to find the right way to execute the transformation, she also strictly enforced accountability and quickly took action in response to poor performance.

Capturing the Opportunities

Several situations present opportunities for CFOs to emphasize the importance of performance transparency and demonstrate how the finance function can play a forward-looking role in driving a transformation’s success. For example, the CFO can support a new CEO or other new members of the executive team in understanding the company’s cost structure, performance development, and ongoing improvement initiatives. These insights help executives identify the most important value drivers and determine whether a transformation is needed. There is a strong case for a transformation if the company is struggling to meet shareholder expectations. In such a situation, the CFO should initiate a fact-driven discussion in which executives assess the need to redesign the company’s operating model or radically improve its cost position.

If a transformation is already under way, the CFO should be alert for inflection points that could be opportunities to significantly influence the program’s impact. In an early phase, the CFO can step up to a greater role if the company lacks transparency into baseline performance or initiatives’ progress or has not adequately prioritized improvement projects or established clear accountabilities. During solution development and implementation, the CFO should assess the transformation through a value lens, especially if it is not meeting expectations for impact and project teams are not able to make course corrections to get it on track.

To enable the CFO to assume an expanded role, most companies will need to strengthen the finance function. For example, an energy company reinforced the function by creating a master data system that provided a single source of truth, improving cost allocation and building skills to continually assess performance and competency gaps. The function’s enhanced capabilities allowed the CFO to support the business through better transparency into cost performance, capital allocation, and investment headroom. In addition, it produced detailed information on how the company creates value, giving the CFO a foundation for constructively challenging business leaders, identifying performance gaps, and proposing ways to close them.

To ensure transparency into performance, the CFO must collaborate with other company leaders to foster a culture of truthfulness in assessing and reporting on progress. Employees at all levels of the organization must be ready and willing to convey bad news about performance, and executives should reward them for doing so. The transparency enabled by a culture of truthfulness provides the basis for the forward-looking decisions required to design and execute a successful transformation. By leading the efforts to create transparency and apply a value lens, CFOs can help guide their companies to more substantial and enduring performance improvements.