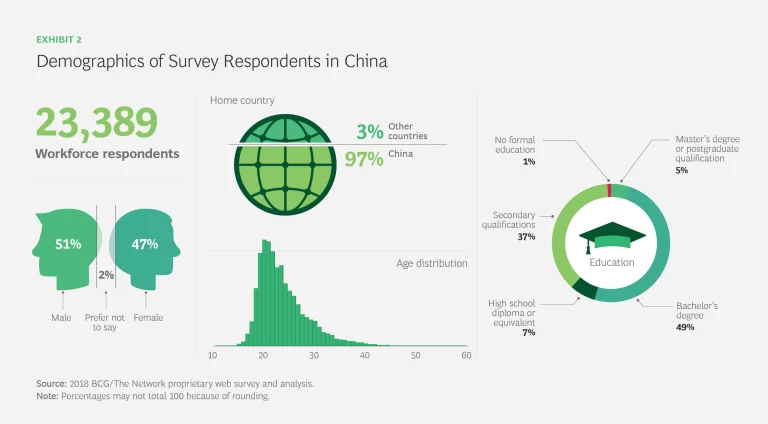

This article is part of the series Decoding Global Talent 2018 . The series is based on a survey of 366,000 workers in 197 countries by The Boston Consulting Group, The Network, and (in China) Zhaopin and ChinaHR.

F our years ago, Chinese residents were close to the global average in their willingness to consider a job abroad. Today, they are among the most reluctant workers anywhere to leave home.

China’s booming economy is creating jobs in unprecedented numbers, including digital jobs in e-commerce, online entertainment, finance, and smart manufacturing. The new jobs—many of them paying as much as comparable positions in the US and Europe and offering a faster career track—go a long way toward explaining why relatively few Chinese have an interest in working outside the country.

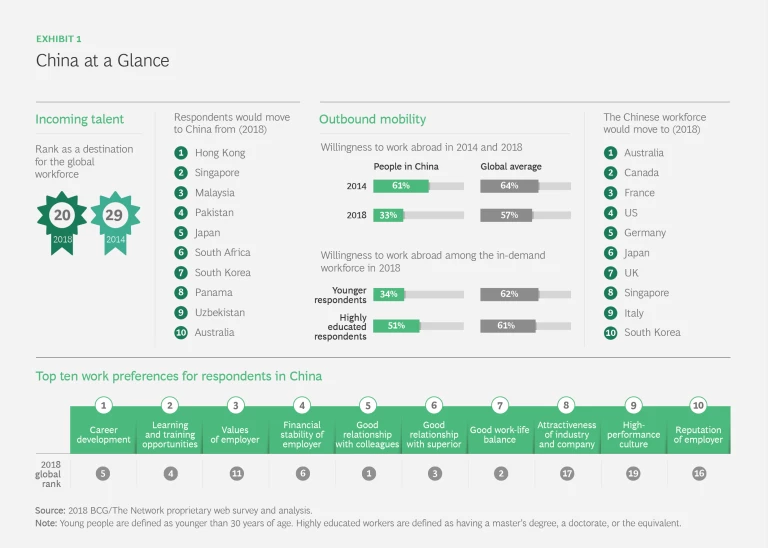

Only one in three Chinese residents is willing to move abroad for work, according to a survey by BCG and The Network. That is down from 61% who were willing to work abroad in 2014, and it makes China one of the countries with the lowest percentage of mobile respondents in the world.

Read more about the featured countries

Read more about the featured countries

- The US Is Still the Top Work-Abroad Choice, but Its Pull Is Waning

- Germany Rises to Number Two as a Work Destination

- The UK Slips as a Hot Spot for Global Talent

- France Remains a Top Draw but Still Needs More People

- Switzerland’s Appeal Endures Despite a Dip

- Russia Faces a Talent Conundrum

- Turkey’s Employers Must Capitalize on Ambitious Talent

China’s Strong Economy Creates a Big Draw

The desire to stay in-country applies to people with especially sought-after skills and profiles, including people younger than age 30. Only 34% of young Chinese are willing to move abroad for a job, far below the global average of 62%. (See Exhibit 1.) In addition, just 51% of Chinese who are highly educated, with a master’s degree or doctorate or the equivalent, would be willing to leave the country for a job, compared with a global average of 61%.

In addition to Chinese who prefer to remain in the country for work, China’s strong economy makes it a bigger draw as a place to relocate for a job than in the past. China is now the 20th most popular destination worldwide, according to survey respondents. That’s a rise from 2014, when China was number 29.

China’s overall attractiveness helped make its major cities more popular as well. In 2018, Beijing is the 41st most popular choice for people willing to move abroad for a job, compared with 67th in 2014, according to the survey.

Survey respondents most interested in moving to China come from several Southeast Asian regions, including Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, Japan, and South Korea. Many of the estimated 50 million ethnic Chinese living outside China make their homes in those regions. The geographic proximity and, in some areas, shared ethnicity, language, and culture could make relocating for work easier for residents there. China is also a top destination for respondents from Pakistan, South Africa, Panama, Uzbekistan, and Australia.

Becoming a Global Innovation Leader

The widespread digitization of business operations in multiple industries and the Chinese government’s Project 2035 initiative to become a global innovation leader are expected to create up to 415 million digital-economy jobs in the country by that year. (See Year 2035: 400 Million Job Opportunities in the Digital Age , BCG report, March 2017.)

Digitization and the Project 2035 initiative are expected to create up to 415 million digital-economy jobs by that year.

The booming economy offers overseas Chinese willing to return home a faster career track than might be available to them elsewhere, one with more opportunities to advance quickly through the ranks into decision-making positions. It also offers them the chance to work for major Chinese companies such as Alibaba and Tencent, with their world-famous founders, and at digital-economy startups operating in one of the world’s most massive markets.

Such opportunities are a big draw. Chinese national Eric Li, 43, an IT executive, worked in the US and UK before moving back to Shanghai. Li, a participant in our survey, says that the primary reason he and his wife returned was to raise their children, now 5 and 10, closer to family. But he is happily taking advantage of the fast-changing economy. “China is a growing market, in particular for digitalization,” says Li, who runs digital solutions for a large facility management company.

Opportunities are also prompting more Chinese students who graduate from US universities to return home instead of staying to work in hot spots like Silicon Valley. The number of graduates returning to China after studying abroad has more than doubled since 2011, according to ICEF.

More Chinese students who graduate from US universities are returning home.

New government policies are encouraging work-related migration of overseas and ethnic Chinese. In early 2018, the Chinese government began offering visas that extend, from one year to five years, the time that people with Chinese ties can stay in the country for a job. The visas are open to children of current or former Chinese citizens and to people who were previously Chinese citizens. The government also recently began offering work visas for up to ten years to foreign-born scientists, entrepreneurs, and other highly skilled professionals.

We interviewed US journalist Scott Fagerstrom, 62, who moved to Beijing in 2017 for a job as an editor at an English-language newspaper, the kind of position that had been increasingly difficult to find at home as the US news business contracted on diminished advertising revenue. Fagerstrom says he enjoys the fast pace of his work and learning about a country that’s new to him. When he’s not working, he likes to hop on the high-speed train from Beijing to other parts of China, including Tianjin, which he calls “an old European settlement that I’ve fallen in love with.”

Competition for a Highly Skilled Workforce

The transition to a digital economy is creating competition for people with desirable skills. Job hunters with deep industry knowledge on top of digital skills are especially in demand. Jobs in sales, engineering, IT and technology, science, and research along with other positions requiring advanced skills or education are hardest to fill, likely reflecting a shortage of skilled labor at a time of rapid economic expansion.

Unlike employees in countries with mature economies, who tend to value work-life balance over other job factors, Chinese survey respondents cite career development and acquiring new skills as the most important elements of a job. The respondents are typically young, single, and in the early phase of their careers, which may partly explain their interest in career development. (See Exhibit 2.)

Two trends—the establishment of tech giants and the transition to digital across many fields—create better opportunities for career development than are available in countries with more-established or slower-growing economies.

Chinese survey respondents rate company image, employer reputation, and an industry’s attractiveness much higher than the global average. The high value that these respondents ascribe to such factors could indicate that they value a company’s brand more than people in other parts of the world do and want to work for organizations that are well thought of and attractive. If that is the case, companies cannot rely on high salaries alone to attract job applicants; rather, they must be aware of how they stack up against other employers.

Toward that end, Chinese companies also offer competitive compensation packages, with perks such as stock options and signing bonuses, and benefits like paid family leave. To be more attractive, some companies also throw in extras such as housing allowances. The one-year contract that Fagerstrom signed included company-subsidized lunches and dinners and a housing allowance for the condo he lives in, which is a hundred yards away from his office.

With its fast growth and large population, China is widely expected to become the world’s biggest economy, surpassing the US. That could make the country even more appealing as an overseas work destination. “This is a chance of a lifetime,” Fagerstrom says, adding: “If I could work for Jack Ma at Alibaba or Pony Ma at Tencent, I would.”