Around the world, economic growth is slowing down. In developed and emerging economies alike, growth rates have declined considerably from their peaks, and there is little evidence that they will rise substantially any time soon. Anemic expansion of labor productivity is largely to blame. As Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman wrote in The Age of Diminished Expectations, “Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.”

True, many factors can affect the rise and fall of labor productivity in the short term, including political instability, changing regulations, business cycles, technology investment, and the difficulty of improving the service sector’s productivity. But we believe that the underlying cause of the recent slowdown has been the ongoing, long-term rise of complicatedness, a phenomenon we first measured in one of our previous publications on Smart Simplicity, “Smart Rules: Six Ways to Get People to Solve Problems Without You.”

We recently surveyed executives and employees at more than 1,000 companies about their perceptions of the nature and degree of complicatedness at their organizations. The results highlight the strong connection between complicatedness and performance and indicate where companies should concentrate their efforts to simplify.

Keep It Simple

The business world is indeed complex, and getting more so, as global competition increases and new technologies offer even more ways of operating and connecting with customers. Companies that develop strategies and design processes to respond quickly and effectively to their complex business environments can gain a significant competitive advantage over their peers.

Instead, however, most companies react by piling on new levels of complicatedness in hopes of meeting external complexity head-on. The resulting changes kill reaction time and productivity through cumbersome structures, new rules, and inefficient processes. For example, companies might address a product quality problem by adding a dedicated organizational unit that introduces more rules, governance mechanisms, and meetings.

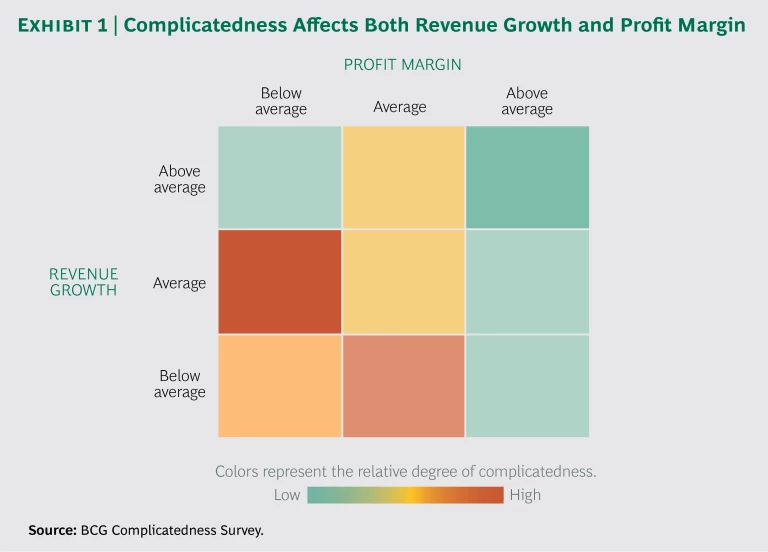

But our study demonstrates that less complicated companies achieve revenue growth and profit margins that are both above average. (See Exhibit 1.) This suggests that complicatedness hampers growth by slowing innovation and the deployment of new products and services. And it cuts margins by injecting inefficiency and cost into operations.

Where, specifically, does complicatedness take its toll? We asked survey respondents to score their company’s degree of complicatedness in each of eight dimensions that we identified for them. (See the sidebar.) This in turn enabled them to place their companies on a spectrum of complicatedness and understand how best to simplify their organizations.

The Eight Dimensions of Complicatedness

Excessive complicatedness can be found in any or all of the following dimensions. Reducing it must begin with changes to the leadership dimension, which binds together and affects each of the other areas:

- Leadership. Management by example, role modeling, and definition of rules and procedures for adhering to them.

- Strategy and Transformation Agenda. Overall vision and strategy, processes for executing and cascading initiatives throughout the organization, and values.

- Structure. Organizational layers, reporting lines, and spans of control.

- Activities and Roles. Definition of roles and responsibilities for units and employees.

- Processes, Systems, and IT. Definition of rules and policies for business processes as well as the supporting IT infrastructure.

- Decision Making. The hierarchy of decision-making authority and the escalation of decisions up through the organization.

- Performance Management. Oversight of business through aligned processes, KPIs, and rewards.

- People and Interactions. Staff development, career paths, engagement, and meeting culture.

Striving for simplicity involves more than addressing a single dimension of complicatedness, however. All the dimensions are deeply interconnected. Efforts to reduce complicatedness one dimension at a time will not succeed—the other dimensions must be considered simultaneously. For example, organizational structures and processes typically increase in complicatedness as new units and functions arise. But these dimensions cannot be sustainably simplified without also improving leadership, communication of company strategy, definition of roles and responsibilities, staff interaction and development, and establishment of incentives.

Characteristics of Complicatedness

Our results provide valuable insight into how complicatedness affects different kinds of companies. For instance, we explored whether company size has a significant effect on the level of complicatedness; larger companies, we predicted, would be more complicated. But that proved not to be the case: complicatedness can affect even the smallest companies if their processes, systems, and cultures hamper efforts to respond effectively to changing market conditions and customer demands.

Although company size is not an influential factor, our findings show that complicatedness varies by industry. For example, technology, media, and telecom companies appear to be less burdened by complicated structures and processes that might slow their ability to react to fast-changing markets. In contrast, organizations in health care and the public sector—which face daunting levels of external complexity, greater levels of regulation, and more government control over their operations—seem to have mimicked that complexity within their own organizations.

Finally, we compared how respondents at different levels of a company view complicatedness; here, the results are particularly striking. Overall, the perception of complicatedness directly parallels respondents’ level of managerial responsibility: complicatedness scores from employees with no managerial responsibilities are 70% higher than those from members of the board of directors.

This finding goes straight to the heart of what may be a primary cause of complicatedness. Every organization’s top leaders have a substantial impact on its degree of complicatedness. Yet as a rule, they fail to perceive just how much their company’s complicated activities, processes, and interactions reduce employee productivity. They are not regularly in the trenches, so they rarely feel the painful effects of complicatedness.

Moreover, they typically don’t need to live by the many rules and procedures they create and instead can work outside the systems that apply to their workers. Our findings suggest that many managers take little responsibility for how complicated life is for their employees. Many of them even believe they are quite successful at reducing it.

But if company leaders and senior managers don’t have an accurate view of the degree to which complicatedness affects their companies, then any effort to simplify it becomes much more difficult. That’s why it is critical to survey all layers of an organization when assessing its degree of complicatedness.

Benchmarking Complicatedness

Our survey also allows executives to assess their companies’ level of complicatedness. By taking the survey (available at https://www.113.vovici.net/se/13B2588B6597EE20 ), they can see their companies’ complicatedness levels not only in absolute terms but also in relation to customized peer groups of similar organizations. The results will provide a sound foundation that companies can use as a starting point for their own simplification programs.

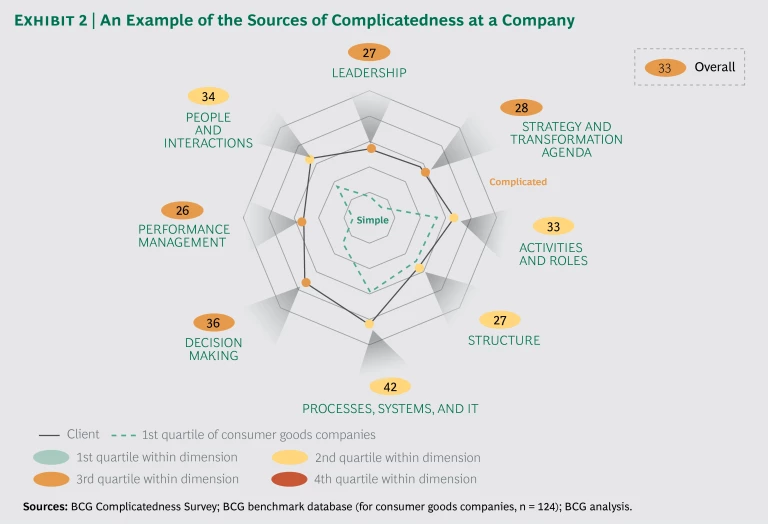

Exhibit 2 illustrates how one consumer goods company used the survey to identify its sources of complicatedness. Although the company’s absolute scores in some dimensions (such as activities and roles; people and interactions; and processes, systems, and IT) are quite high, the scores are still within the second quartile of all companies in its industry.

More significant—and more worrisome—are its relatively poor third-quartile scores in the leadership, strategy and transformation agenda, performance management, and decision-making dimensions. Taken together, these scores suggest that, although the company is relatively free of excessive complicatedness at the moment, it is substantially at risk of future problems. Complicatedness at the top is likely to lead to poor communication with lower-level managers and employees. And that, in turn, could soon cause growing levels of complicatedness throughout the company.

The Simplification Solution

Benchmarking can help every company understand how complicatedness affects its productivity and performance. But it is only a beginning; we recommend a four-step approach to implementing a lasting solution:

- Smart Start. Identify performance issues caused by complicatedness—through belief audits, for example. Conduct high-level context evaluations such as the BCG Complicatedness Survey. This will uncover the complicatedness dimensions that require further analysis.

- Diagnosis. Understand the root causes of performance problems by analyzing why people adopt unproductive behaviors. This is typically accomplished through in-depth employee interviews focusing on specific issues that are linked directly to the performance problems identified—for instance, how a lack of cooperation among store employees and managers, regional sales management, and headquarters impairs store performance.

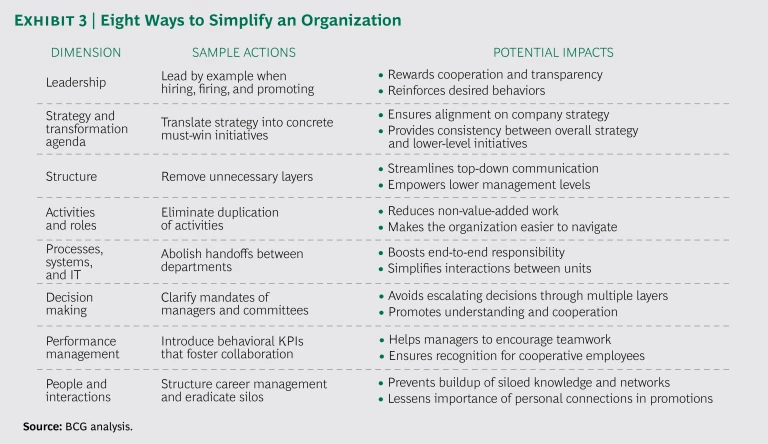

- Solution Design. Develop interventions that address the underlying causes of specific performance issues. Such interventions should consist of carefully targeted changes that promote desired behaviors and produce a clear and measurable impact on performance. Exhibit 3 outlines several possible interventions for each dimension and their potential impacts. For example, reducing duplication of tasks can significantly simplify employees’ activities and roles while boosting efficiency throughout the organization. But remember that no single intervention will cure larger, systemic performance ills.

- Implementation. Apply the specific interventions by establishing a project management office to prioritize solutions, create an implementation road map, drive the change process, and monitor improvement.

This approach was instrumental in helping one large company reach its digitalization goals. The company had developed a comprehensive digitalization agenda, but implementation was slow and employees were reluctant to adopt the new digital tools.

Rather than leveraging one of the new tools for managing their customer pipeline, for example, many salespeople were reverting to conventional solutions such as Excel spreadsheets. Our analysis reveals that this behavior was driven by the actions of supervisors, who were using the new tool to micromanage the sales force, demanding detailed follow-ups and unrealistic sales projections. As a result, the salespeople would simply rework their Excel data so that it would meet their supervisor’s expectations in the new system.

To change this behavior, the company promoted a more supportive leadership style. At the most practical level, the tool was redesigned to restrict the level of data granularity that supervisors could see. This prevented them from overmanaging employees while still allowing supervisors to use the tool to guide sales planning.

(For more details on complicatedness, its relationship to context, behavior, and performance, and our approach to simplification, see Mastering Complexity Through Simplification: Four Steps to Creating Competitive Advantage , BCG Focus, February 2017.)

Every company is looking for the path to faster growth and higher profits in an increasingly complex and competitive business environment, and many are struggling to find it. Rather than blaming external factors for their troubles, successful company leaders examine their own organizations more closely. In doing so, they identify where complicatedness has crept into many of their processes, systems, and activities.

Rooting out complicatedness is possible but only with a structured and focused simplification effort. Business leaders following this road will harvest the fruits of improved productivity and gain a competitive advantage for their companies.