“Business success contains the seeds of its own destruction. Success breeds complacency. Complacency breeds failure.”

–Andy Grove, former CEO and Chairman, Intel

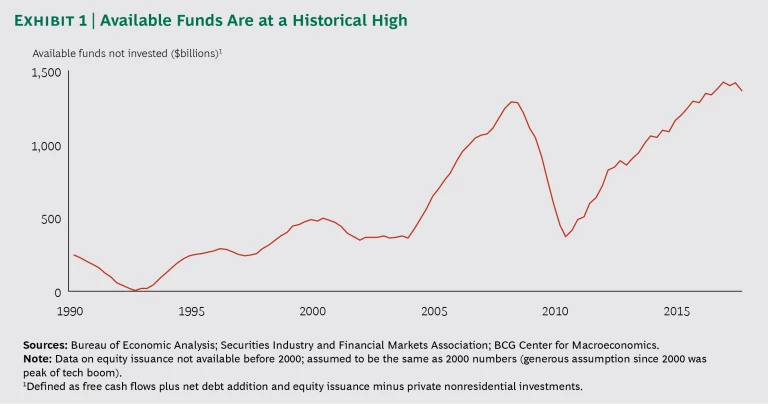

B y traditional performance metrics, large businesses are in a more comfortable position now than they have been for several decades, with record-level S&P 500 profits and cash balances. (See Exhibit 1.) Economic conditions have been supportive, delivering broad-based growth across all major markets.

Large businesses are capturing an increasing share of the pie, with revenues becoming increasingly concentrated in many industries. Firms have therefore been able to keep wages and investment levels low while simultaneously borrowing money at low interest rates.

Still, there are some plausible reasons for large businesses to be prudent and vigilant about how long the good times will last, at the level of the individual firm and the whole economy.

Risks on the Horizon

First, technological innovation continues at a dizzying pace. Incumbent enterprises continue to be disrupted by digital attackers, often from beyond familiar industry boundaries. As a result, as 2018 starts, seven tech companies are among the top ten global firms by market capitalization (Apple, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, Alibaba, Tencent), compared to one only a decade ago.

This is only the visible tip of the iceberg. With Fortune magazine, we developed a ranking of the most vital US companies—those with the highest potential and capacity to grow in the long term. The Fortune Future 50 index shows the extent to which tech firms threaten traditional incumbents: the tech sector represents only 15% of the top US firms by revenue but 24% of today’s fastest-growing companies and 64% of the Fortune Future 50.

Second, today’s macroeconomic environment is fragile. Even as a cyclical recovery from the financial crisis continues around the globe, structural factors threaten global growth in the long run, as Christine Lagarde, head of the International Monetary Fund, opined at the 2018 meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos . In an era of secular stagnation, long-term growth rates have fallen across developed economies, and demographic trends will further constrain growth in the future.

Firms cannot take for granted that the favorable business environment will continue uninterrupted.

Third, political and economic uncertainty has increased significantly in the past two years. Income inequality is rising, while trust in business and government is falling, encouraging a populist backlash against two pillars of economic growth: global integration and technological progress. As a result, firms cannot take for granted that the favorable business environment will continue uninterrupted, and this could provide a further drag on performance .

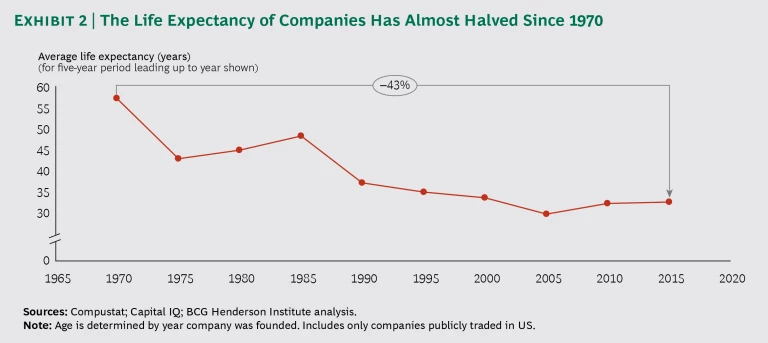

Finally, our research indicates that US companies’ life expectancy is shrinking : it almost halved (-43%) since 1970, and the risk of disappearing—either by bankruptcy or through M&A moves—in five years has risen to more than 30%. (See Exhibit 2.)

How to account for this trend in the context of rising profits and valuations? While the performance of large corporations might be high, their vitality—their capacity for growth and reinvention—is declining in many cases. According to our research , large, established companies are increasingly vulnerable in this respect.

The relative comfort of today's conditions might prevent organizations from acting decisively to address challenges.

Today’s executives are not blind to these risks. For instance, business model disruption and changing global economic conditions are among the top trends feared by business leaders . However, the relative comfort of today’s conditions might prevent their organizations from acting decisively to address these challenges.

Businesses Need to Avoid the Trap of Complacency

Companies are examples of complex adaptive systems, in which local events can have cascading effects on the entire system. In particular, complex systems are susceptible to a sudden collapse, as demonstrated by many historical examples. This property is known as the Seneca Cliff , referring to the Roman author who wrote, “Increases are of sluggish growth, but the way to ruin is rapid.”

How can firms mitigate this risk? As Ugo Bardi, who coined the term, says, “If you want to avoid collapse, you need to embrace change, not fight it.” But this cuts against the natural tendency to be complacent after success, rather than to keep questioning, challenging, and exploring. Complacency can blind leaders to new opportunities. Former Polaroid CEO Gary DiCamillo explained Polaroid’s denial of digital photography’s potential, which doomed the firm to failure, by saying, “The reason we couldn’t stop the engine was that instant film was the core of the financial model of this company.”

A key challenge—and opportunity—for leaders today is to create a sense of urgency in their organizations, in spite of comfortable present conditions.

How to Create a Sense of Urgency amid Comfort

There are several powerful ways in which leaders can create urgency under favorable conditions.

Conduct a maverick scan. Disruption generally happens from the edges of an industry. There are usually many companies on the periphery of an industry that are taking bets against the business models of incumbents. Many will be startups, which are statistically unlikely to succeed, although their ideas might. But if it is hard for venture capitalists to judge which ones will break through, it is even harder for incumbents, who are likely to be wedded to their current business models. By inspecting these mavericks closely and asking, “What if their bet against our business model succeeded?”, firms can create a sense of urgency and generate specific ideas on where to innovate and invest.

Survey “bad” customers. Because current customers have already decided to buy a firm’s products, surveying them often generates misleading positive responses, even in industries on the brink of disruption. To create a sense of urgency, it is sometimes more useful to survey noncustomers, defected customers, and dissatisfied customers. Posing the right questions also helps: asking about hopes, fears, and challenges might yield more information about future opportunities than asking about satisfaction with current offerings. And customers often are not explicitly aware of their unmet needs, so questionnaires must be supplemented by careful field observation. Most organizations are more willing to listen to a customer than to an internal change advocate, so outside-in signals are invaluable in creating a sense of urgency.

Most organizations are more willing to listen to a customer than to an internal change advocate.

Construct stress scenarios. It is hard for an organization to be successful if it does not believe in its current business model. However, it can also be fatal not to be paranoid about the vulnerability of one’s current model and plans, especially in an environment where corporate life expectancy is declining. Firms can commit to their current plans while provoking urgency by thinking through the consequences of low-probability but high-impact competitive and environmental scenarios.

Conduct a “destroy your business” war game. Jack Welch famously launched “destroy your business” exercises at GE during the e-commerce boom to mobilize his organization. By executing war games, in which one team defends and another attacks the current business model, leaders can vividly sensitize an organization to vulnerabilities and opportunities. And framing the exercise as a game legitimizes dissent and creative thinking, which may ordinarily be muted. Finally, the self-discovery of contingencies fosters deeper understanding and commitment than top-down analyses and pronouncements ever could.

Look at neighboring industries and geographies and ask why not? A business model is not disrupted until it is, by which time it’s usually too late to react. Similarly, skeptics of the need for change are correct until they are not. Organizations need to legitimize contingent thinking by entertaining counterfactuals—things that have not happened yet but could happen in the near future. Looking at disruptions in neighboring industries and geographies and asking why not is a powerful way to expand strategic thought and create an appropriate sense of urgency.

Entertain counterfactuals—things that have not happened yet but could happen in the near future.

Map and eliminate frictions. The above measures focus on reacting to emerging threats early enough to forestall them. But the surest way to avoid threats and shape the future is to create them. The Japanese word for crisis, kiki, means both danger and opportunity. Pioneers emphasize the latter. All industries exhibit “frictions,” including distribution markups, contract complexity, and delays, which are often taken for granted. Pioneers can map and measure these frictions, innovating to proactively eliminate them before any customer or competitor has even thought about doing so. A sense of urgency is created by making visible to leaders what could be done—and thus what eventually will be done by a competitor, if they don’t act first.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit

Featured Insights

.