The first thing that Aditya, 23, does when he wakes up at 7 in the morning is check the messaging app on his smartphone. That is also the last thing that Aditya, a postgraduate student living with his parents and younger brother in one of India’s big cities, does before he goes to bed 18 hours later.

In between, Aditya (we’ve changed his name) is never far from his smartphone. He uses it to listen to music on his way to his university classes, to look for deals on e-commerce sites, and to Skype with a friend who is studying abroad. Dinner table discussions of where to go on a holiday or what television to buy are usually informed by something that Aditya is looking at in real time on his phone.

India, China, Brazil, and other emerging markets are home to a lot of people who, like Aditya, rely on the internet either to make or to guide their purchases. As of 2017, upward of 2.1 billion internet users lived in emerging markets. By 2022, that number will likely swell to around 3 billion, and three times as many internet users will live in emerging markets as in developed markets.

In terms of growth, emerging-market digital consumers represent an enormous opportunity. Even when such consumers don’t buy directly on the internet, information that they find online—typically on a smartphone—often influences their purchasing decisions. Four years from now, the total value of digitally influenced spending in emerging markets will approach $4 trillion, according to our estimate.

For this report, The Boston Consulting Group’s Center for Customer Insight (CCI) surveyed more than 15,000 internet users to develop a picture of where emerging markets are in their digital development. We did in-person interviews with 1,000 or more people in each of nine countries: Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, the Philippines, and South Africa. All of our interviews were conducted in urban areas, where the connectivity level is highest and internet use is most engrained.

Digital’s Surging Influence

Emerging-market economies have advanced dramatically in the past two decades. From 2000 to 2016, these countries’ share of the world’s gross domestic product rose from 11% to 28%, according to the World Bank, and their share of global household consumption expenditures rose from 11% to 24%.

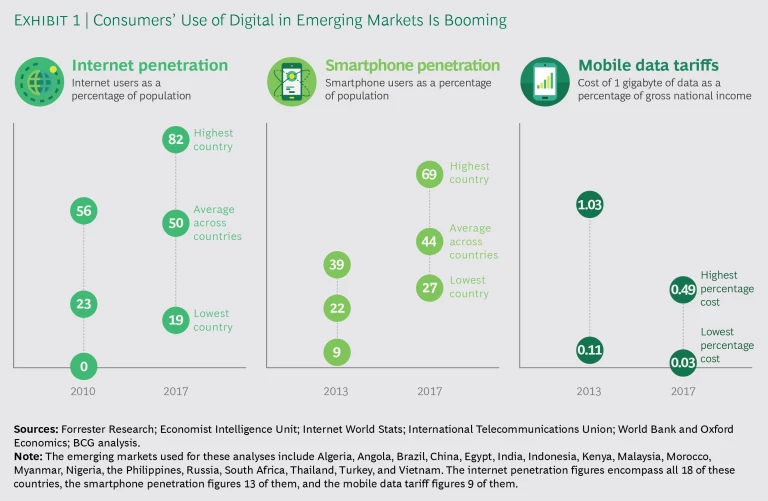

Falling smartphone prices—down by an average of 40% in emerging markets from 2011 to 2016—have put these devices in the hands of hundreds of millions of emerging-market consumers who previously could not afford them. Another change has been the arrival of high-speed data networks, which are now almost as ubiquitous in emerging markets as in developed markets such as the UK and the US.

Together, these factors have enabled emerging markets to make spectacular advances in their levels of internet connectivity. Half the population in emerging markets worldwide is now connected to the internet, compared with less than a quarter in 2010. (See Exhibit 1.) The connected population is even higher (above two-thirds) in parts of Southeast Asia and in Russia, Turkey, and Brazil.

Internet users in emerging markets now outnumber internet users in developed markets by more than two to one, and the difference is widening. Emerging markets will contribute approximately 900 million new internet users between now and 2022, versus about 80 million new internet users from the world’s already heavily connected developed markets. So in the next few years, more than 90% of all new internet users will come from emerging markets.

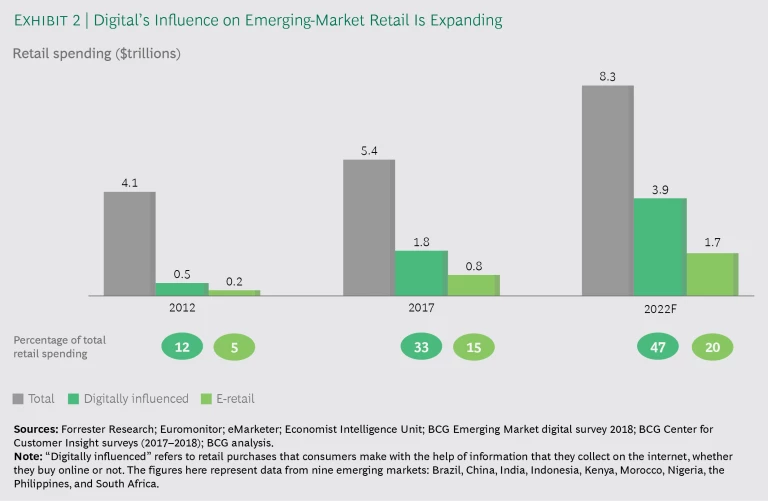

Emerging-market internet users are starting to use the internet for commercial purposes. E-retail revenues in the biggest emerging markets rose to $800 billion in 2017, a figure that represents 15% of all retail revenues in those markets. And that number is dwarfed by the volume of digitally influenced purchases, which amounted to about $1.8 trillion last year and should grow to a staggering $3.9 trillion by 2022. (See Exhibit 2.) At that point, almost half of all emerging-market retail spending will reflect some type of digital influence.

How Digital Influence Differs, by Country

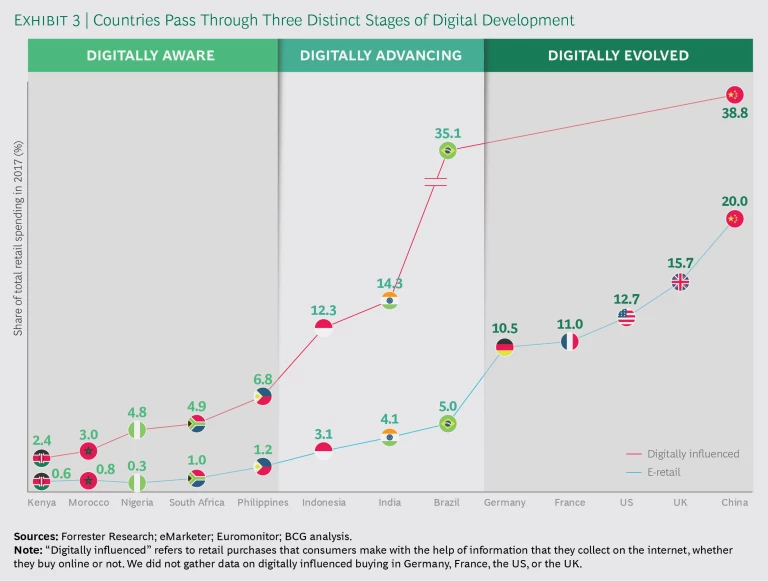

The nine countries that CCI studied fall into three broad stages of digital development. The earliest stage, which describes the situation in the Philippines and in the four African countries in our survey, is digitally aware. At this stage, e-retail accounts for only a tiny share (usually less than 2%) of the country’s total retail sales, but digital influence is growing rapidly; approximately $1 of every $20 spent in retail settings is digitally influenced.

The next stage is digitally advancing. At this stage, e-retail accounts for a higher but still small percentage (3% to 5%) of the country’s retail revenues, and the proportion of digitally influenced retail expenditures is 12% to 35%. Of the nine countries we examined, Indonesia, India, and Brazil are in the digitally advancing category; of these, Brazil is the farthest along.

Finally there are the digitally evolved countries, where e-retail accounts for more than 10% of all retail revenues, and where consumers commonly do online research before buying things. Most of the countries that have reached this stage are Western, but China is an exception and in fact is one of the most advanced countries in the cohort from the vantage point of how its consumers use digital technology. (See Exhibit 3.)

Countries can advance through the maturity stages quickly. Five years ago, India, Indonesia, and China were all at earlier stages—digitally aware in the cases of India and Indonesia, and digitally advancing in the case of China. But the five-year average growth rates for e-retail in these countries (59% in India, 32% in Indonesia, and 46% in China) have pushed each of them into a more advanced stage of digital maturity. Once e-commerce gets going in an emerging market, it generally develops, one might say, at light speed.

Category Differences

In all emerging markets, air travel is the category most subject to digital influence and most likely to be bought online. Strong digital influence is also evident in the mobile phone category. Apparel and footwear see a lot of e-commerce, too, though not until the digitally advancing stage.

Automobiles and large appliances show high levels of digital influence but low levels of e-commerce. Consumers generally prefer to see and touch these big-ticket items before purchasing them. Consumers also have concerns about the level of support that retailers will provide for products bought online in these categories.

Food purchases show few signs of digital influence; most consumers neither research nor buy food online. The low influence of digital in food buying is related to the nature of the category, where freshness is paramount.

Shifts in Consumer Behavior

When a country’s markets advance from one digital stage to the next, consumer behaviors change, too. One of the most obvious changes is in the expectation of a better experience, whether that means something practical like a good recommendation engine or something fun like the ability to see oneself in a shirt or hat that one is considering buying. Altogether, 81% of people in digitally evolved markets say that they look for a fun or enjoyable experience in deciding where to buy. By contrast, the shopping experience matters to only about one in four people in digitally aware markets, and to only one in ten people in digitally advancing markets.

How People Shop. The percentage of consumers who do most of their shopping through online marketplaces is very high at every stage of development, reaching 79% in China, the most digitally evolved market in our study.

Getting the next-most votes for preferred shopping format is social media, whether in the form of a brand’s social media account or of peer-to-peer transactions. Peer-to-peer buying is especially popular in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand. Consumers in those countries see peer-to-peer commerce as a way to find bargains and unique products that would otherwise not come to their attention or that aren’t available in online marketplaces that are accessible to them. Peer-to-peer purchasing can also increase consumers’ degree of trust in online. That was the case with one Thai consumer we talked to, who bought a camera lens from someone in his photography enthusiast group on Facebook. The consumer viewed the seller as an expert in camera technology.

How People Pay. Another area of difference between digital maturity stages relates to payment methods. Three-fifths of all online purchases in digitally aware markets are cash on delivery. CoD is especially common in the Philippines and Morocco (where it is used for 88% and 86%, respectively, of online purchases). Consumers in these markets aren’t always comfortable with the idea of paying upfront, believing that it may leave them vulnerable if a product isn’t delivered or isn’t what they expected. Low credit card penetration in these markets is another barrier, making prepayments impractical in many cases.

By contrast, in more digitally mature countries, digital payments, not cash, are the usual mode for e-commerce transactions. Among online shoppers in China, 66% say that they prefer to use an online mobile wallet or payment service for their online purchases; another 28% prefer to use a debit or credit card. In Brazil, too, there’s almost no such thing as cash on delivery in e-commerce; most Brazilians (75%) default to a debit or credit card, both of which are widely used in the country.

A New Era Has Dawned

In big cities in emerging markets nowadays, more people than not seem to have mobile phones in their hands as they walk down the street. That’s true of Shanghai, of Delhi, of Johannesburg, and of dozens of other places where, in effect, digital vanguards have emerged. Not every consumer who has a smartphone in these places uses it to buy things from e-commerce sites. But such consumers may use it to collect information for an offline buying excursion. And if they aren’t doing so today, they will be tomorrow.

The move in the next four years toward $4 trillion in digitally influenced retail purchases is a wake-up call for every retailer and manufacturer operating in these markets. This is a shift that no manufacturer or retailer can afford to ignore.

About BCG’s Center for Customer Insight (CCI)

Boston Consulting Group’s Center for Customer Insight (CCI) applies a unique, integrated approach that combines quantitative and qualitative consumer research with a deep understanding of business strategy and competitive dynamics. The center works closely with BCG’s various practices to translate its insights into actionable strategies that lead to tangible economic impact for our clients. In the course of its work, the center has amassed a rich set of proprietary data on consumers from around the world, in both emerging and developed markets. The CCI is sponsored by BCG’s Marketing, Sales & Pricing practice and Global Advantage practice. For more information, please visit

Center for Customer Insight

.