The economic integration of Southeast Asia—which would turn a region with a population of 650 million and a nominal GDP of $6.5 trillion into one of the world’s biggest and most dynamic emerging markets—has been an aspiration of forward-thinking regional leaders for nearly three decades. The project has been furthered by the work of the ten-nation Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and was most recently boosted by the signing of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Now a powerful new force—the rapid adoption of digital technologies by the region’s businesses and increasingly affluent consumers—is complementing these government efforts by making a common market a reality. Invisible data highways are bridging vast island archipelagos and populations separated by a wide variety of languages and cultures through smartphones, the wireless internet, and social media. Companies are using this connectivity to offer new, accessible services to the region’s consumers. And BCG research finds that digital technologies already heavily influence the purchasing decisions of Southeast Asians.

Digital technologies already heavily influence the purchasing decisions of Southeast Asians.

Look around the region and you’ll find plenty of evidence of digital’s impact on the consumption of goods and services that until recently were relatively inaccessible for most Southeast Asians. New online grocers and marketplaces such as RedMart and honestbee are allowing families in Jakarta, Singapore, and Manila to have Australian organic beets, American rib-eye steaks, Norwegian salmon, fresh Chinese bok choy, and African condiments and packaged teas delivered to their doors. Government agencies and e-commerce giants such as Alibaba are building logistical and technological infrastructure that will soon enable thousands of small enterprises in Malaysia and Thailand to sell their boutique products in neighboring countries. A passion for South Korean fashions, cosmetics, and pop music has gripped young, social media-savvy Filipinos, Indonesians, and Vietnamese.

To capture the enormous opportunities, companies will not only need an ASEAN-wide strategy. They will need a digital ASEAN strategy. By no means does this imply a one-size-fits-all approach to Southeast Asia. To the contrary, companies should identify and engage with the rich new market segments that span Southeast Asia by analyzing the immense data generated by the region’s connected customers.

The digital integration of Southeast Asia is still in its early stages, and different tariff and regulatory regimes will continue to have an impact on the physical movement of goods for the foreseeable future. But businesses can help ASEAN governments gain a better understanding of the evolving digital economy—and how to mobilize it to boost growth. Together, they can make it easier for data to flow across borders by updating regulations and improving data privacy and security. By accelerating digital integration, ASEAN nations and companies can turn one of the world’s most dynamic regions into one of its greatest growth zones for decades to come.

Southeast Asia’s Immense Market Potential

The economic prospects for ASEAN’s ten member nations—Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam—are already strong. The region’s combined population is larger than that of the European Union and nearly double that of North America. Since recovering from the Asian financial crisis of 1997, Southeast Asian economies have posted some of the world’s most stable economic growth. The region’s combined 2017 GDP of $6.5 trillion, measured in purchasing power parity, was the equivalent of the world’s fourth-largest economy. With a projected compound annual growth rate of 5%, its GDP is on track to nearly double by 2030.

Only $5.5 billion in e-commerce—less than 1% of total retail sales—was recorded in the region in 2015. But that’s projected to grow explosively, to around $88 billion, or 6.4% of all retail sales, by 2025, according to a study by Google and Temasek. Big investments in logistical infrastructure and expanding partnerships within the e-commerce ecosystem are rapidly extending the geographic reach of digital platforms and sharply lowering the costs of linking buyers and sellers across the region.

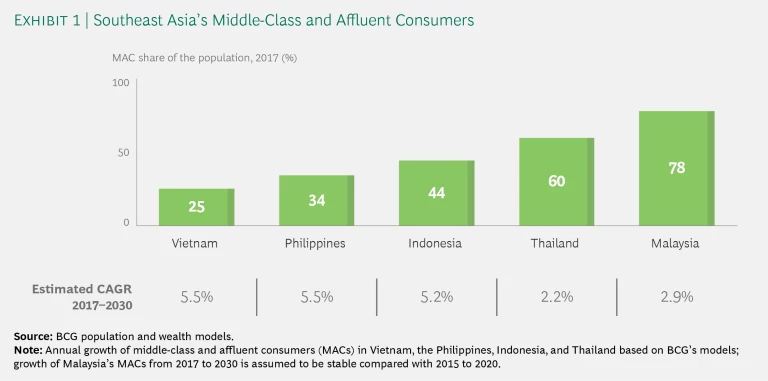

Southeast Asia remains an immensely diverse region economically. It includes highly developed economies such as Singapore, middle-income economies such as Malaysia and Thailand, rapidly developing economies such as Indonesia and the Philippines, and frontier markets such as Vietnam and Myanmar. The percentage of middle-class and affluent consumers (MACs), which is the key consuming class, likewise varies widely. (See Exhibit 1.) Examine these economies closely, however, and you’ll find that several overarching economic and social forces are increasingly unifying ASEAN as a consumer market and reframing consumer opportunities beyond national boundaries.

Megatrends Binding Southeast Asian Consumers Together

Among the powerful megatrends that are particularly relevant for companies developing digital ASEAN strategies are increasing affluence, urbanization, and a growing demand for convenience.

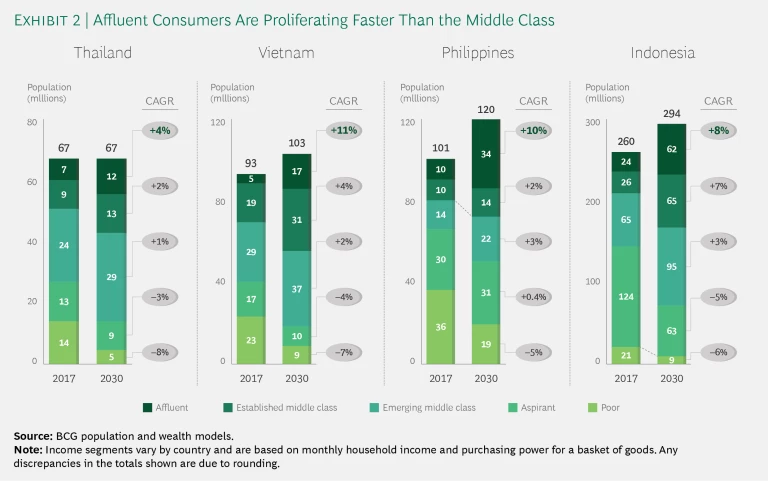

Increasing Affluence. One of the great global economic stories of the past few decades has been the ascent of hundreds of millions of Southeast Asians out of poverty and into the middle class. While this is continuing—with the percentage of Southeast Asians in the MAC category projected to rise from 40% now to 64% in 2030—even faster growth in the ranks of the affluent, specifically, is a more recent trend. We define the affluent in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam—Southeast Asia’s four most populous nations—as people in the top 10% of the income pyramid, depending on the country. (For an explanation of income groups within Southeast Asian populations, see the sidebar, “BCG’s Method for Classifying Household Income Segments.”) In these four economies, the affluent population is growing at an 8% annual clip. In the Philippines, for example, the affluent are growing at 10% a year, compared with around 2% growth in the group we call the “established middle class.” BCG’s Center for Customer Insight projects that an additional 78 million consumers in these four countries will be regarded as affluent by 2030. (See Exhibit 2.)

BCG’S Method for Classifying Household Income Segments

BCG’S Method for Classifying Household Income Segments

A model developed by BCG’s Center for Customer Insight segments the populations of Southeast Asian countries into five groups on the basis of monthly household income, census data, and purchasing behavior. The income segments are: poor, aspirant, emerging middle class, established middle class, and affluent.

The income bands for these segments are different in each country, since they measure the purchasing power for a basket of goods. In Southeast Asia’s four most populous nations—Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam—the percentages of people in each income segment are as follows:

- Affluent. Across all four countries, an average 9% of the population is in the highest income segment, ranging from 5% in Vietnam to 10% in Thailand.

- Established Middle Class. Across all four countries, an average 12% of the population is in the second-highest income segment, ranging from 10% in Indonesia to 21% in Vietnam.

- Emerging Middle Class. Across all four countries, an average 25% of the population is in the middle income segment, ranging from 14% in the Philippines to 36% in Thailand.

- Aspirant. Across all four countries, an average 35% of the population is in this income segment, ranging from 18% in Vietnam to 48% in Indonesia.

- Poor. Across all four countries, an average 18% of the population is in the lowest income segment, ranging from 8% in Indonesia to 36% in the Philippines.

The population of middle-class and affluent consumers in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines comprises the emerging and established middle-class and the affluent segments, but in Myanmar and Vietnam, it comprises only the established middle-class and affluent segments. In Indonesia, MAC households have monthly incomes exceeding $224. In the Philippines, these households have monthly incomes exceeding $465, in Thailand $442, and in Vietnam $660.

This rising affluence is translating into dramatic changes in the hottest growth sectors for consumer products. While demand for modest indulgences such as snack foods and ready-to-drink beverages took off as Southeast Asians entered the middle class, for example, demand is now surging across the region for affordable luxury goods, such as cosmetics and high-end consumer durables, and for “experiential” products like restaurant dining and overseas travel. Moreover, these affluent consumers are internationally minded, discerning, and interested in unique and customized products and experiences—demands that digital commerce is particularly well positioned to fulfill. The choices of affluent consumers also exert a strong influence on the MAC segment overall. In Vietnam, for example, returning expatriates (known as viet kius) are opinion leaders when it comes to lifestyle, fashion, and eating out.

Urbanization. Between 2015 and 2030, the percentage of the population in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam living in cities is projected to rise from 48% to 57%. That would translate into another 87 million urbanites—roughly the size of Vietnam’s population today.

Urbanization is accelerating well beyond such major metropolises as Bangkok, Jakarta, Manila, and Ho Chi Minh City and into so-called tier-two and tier-three cities and districts. For example, BCG projects that the number of tier-one cities—those with more than a million middle-class and affluent inhabitants—will increase from 14 to 47 between 2017 and 2030; but the number of tier-two cities—those with MAC populations between 500,000 and 1 million—is expected to jump from 35 to 98 over that period, and the number of tier-three cities (MAC populations of 200,000 to 500,000) from 90 to 103.

Consumers in Southeast Asian cities are looking for channels that deliver groceries, essential services, and other daily necessities directly to their doors.

Urbanization is transforming Southeast Asia’s consumer economy in several fundamental ways. It is driving economic growth, stimulating demand for services, and creating big concentrations of middle-class and affluent consumers with common tastes and interests. Infrastructure challenges in key cities and other factors are driving the growth of the digital economy. Where merely making a U-turn in heavy traffic can take half an hour, for instance, access to home delivery can be a major advantage.

Growing Demand for Convenience. One outgrowth of increased population density is the demand for convenience. As people spend more time commuting to work, and as traffic congestion grows more severe, Southeast Asian urbanites are already shopping at supermarkets less frequently. Instead, they are buying in smaller quantities at neighborhood minimarts and convenience stores, many of which are open around the clock. Revenue at convenience outlets has been rising at an annual rate of 19% in Indonesia, compared with 8% for all retail channels. In the Philippines, convenience shopping is growing by 22% and in Vietnam by 47%—more than four times faster than overall retail. Convenience stores satisfy the need for food on the go and are blurring the lines between large grocery stores and “top up” outlets.

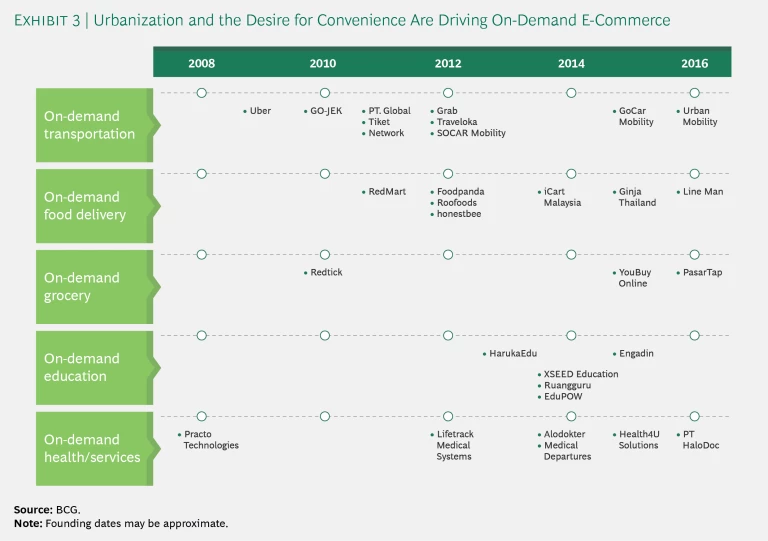

The need for convenience is also fueling the so-called on-demand economy. Consumers in Southeast Asian cities increasingly are looking for channels that deliver groceries, essential services, and other daily necessities directly to their doors. (See Exhibit 3.)

Each of these trends augurs well for the future of e-commerce in Southeast Asia. The rapid adoption of digital technologies and social media will accelerate access to the entire ASEAN market—for companies large and small, whether they are based within the region or outside it.

The Digitization of Southeast Asia

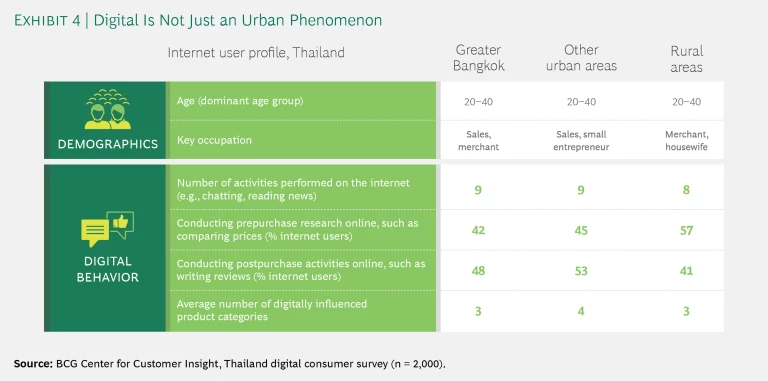

When people think of the penetration of digital technology into average households in an emerging market, China usually comes to mind first. Yet similar digital behavior and trends are apparent in most of Southeast Asia. The average Thai, Malaysian, and Indonesian spends nine hours per day online via PCs or tablets and four hours per day on his or her mobile phone—far more than in China. Southeast Asians living in rural areas or in tier-two or tier-three cities are as digitally savvy as those in big cities. (See Exhibit 4.) In rural Thailand, for example, internet users engage in an average of eight digital activities—nearly the same as in greater Bangkok.

But e-commerce remains underdeveloped in most of Southeast Asia. In Singapore, for example, only 5.5% of retail purchases are transacted online and in Indonesia just 3.1%. That compares with more than 20% in China in 2017, according to Euromonitor. Online marketplaces are important channels for certain products, however—particularly clothing, beauty products, and smartphones. What’s more, e-commerce is expanding rapidly, ranging from 18% to 40% annual growth across the region, according to Google and Temasek. In Vietnam, for example, e-commerce revenues are projected to leap from just $400 million in 2015 to $7.5 billion by 2025, and in Indonesia from $1.7 billion to $46 billion over the same period.

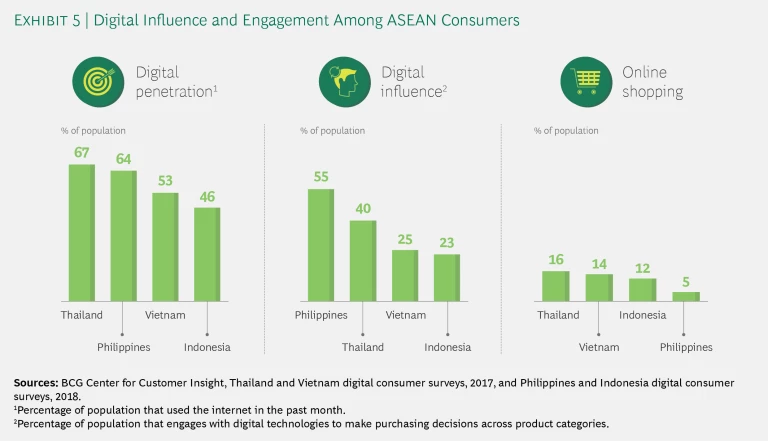

A good leading indicator that e-commerce is poised for takeoff in Southeast Asia is the high level of “digital influence”: 25% of Vietnamese already engage with digital technologies at some stage when making a purchase. Digital influence reaches 40% across all product categories in Thailand and 55% in the Philippines. (See Exhibit 5.)

Amazon, eBay, and omnichannel companies such as Tesco engineered the first digital revolution centered in the US and the UK. Chinese marketplaces such as Taobao and Tmall powered a more rapid digital revolution in China. Southeast Asia has a distinct e-commerce model that mainly revolves around social media, in part because marketplaces were late to develop in the region. Apps such as Instagram, Line, and Facebook Messenger are used for much more than alerting subscribers to flash sales and special promotions. Southeast Asian consumers frequently make purchases through these social media channels. They also like to engage directly through their apps with sellers—often small retailers or individuals offering secondhand items. Such small businesses tend to be more willing to allow cash on delivery and to not require payment by credit card (credit cards are used less frequently in Southeast Asia than in other regions).

Part of the reason for these preferences may be cultural. According to our interviews, many Southeast Asians—like Chinese consumers—enjoy the “treasure hunting” aspect of traditional shopping. Peer-to-peer e-commerce allows consumers to simulate that experience. Buyers can ask small retailers questions about different products, view photos, haggle over prices, and arrange convenient deliveries.

Much of Southeast Asia appears poised to leap directly from cash to digital payments—skipping credit and debit cards. In the US, by contrast, there are 177 credit cards for every 100 people. In Thailand, there are 29 per 100, and in Vietnam only 5. Use of ATMs and bank branches is also much lower than in developed economies across most of the region. But digital payment is growing fast. In Thailand, it has reached 26 accounts per 100 people—even more than in Singapore, the region’s most developed economy—registering 17% annual growth from 2014 through 2017. Digital accounts in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam experienced 75% to 80% annual growth over that period. The next step is to use this trend to drive digital sales. One option might be to partner with Chinese players such as Alipay or regional challengers like GrabPay.

The Rise of Southeast Asian Online Marketplaces

Much work remains to be done in harmonizing tariff rates and regulations before goods can flow freely across borders within ASEAN. There currently is no regionwide system for real-time, cross-border payments, for example, and taxes on e-commerce vary. But technology companies are putting in place much of the infrastructure needed for a regional digital marketplace. The scale and reach of e-commerce platforms are creating enormous new markets for Southeast Asian enterprises, which can now reach hundreds of millions of connected consumers at minimal cost.

Many large e-commerce marketplaces already serve the region; more are arriving fast. In addition to such global giants as Alibaba and Amazon, there has been a proliferation of successful local online providers serving the growing on-demand economy. On-demand transportation ticketing platforms in Southeast Asia include Traveloka and Tiket.com. Grocery home delivery sites include Singapore’s honestbee and Indonesia’s HappyFresh. HarukaEdu, Ruangguru, and XSEED are among Southeast Asia’s providers of on-demand education, while BookDoc and others offer digital health care services.

As logistical and regulatory obstacles are addressed, e-commerce companies will be able to move fast.

Southeast Asians are comfortable using a wide range of online channels for their daily needs. In Singapore, online shoppers can buy wine from Deliveroo, produce from OpenTaste and Cold Storage, and everyday household items from RedMart. These sites are also getting smarter as they adopt technologies such as artificial intelligence and voice and facial recognition. RedMart even simplifies the shopping experience by generating lists based on a customer’s order history.

Some Southeast Asian e-commerce marketplaces are branching out into new segments and building a regional presence. Indonesian platform GO-JEK offers 18 different services, including food delivery, ticketing, and a ride-hailing and logistics site that employs hundreds of thousands of car, truck, and motorcycle drivers. GO-JEK’s app, launched in 2015, has been downloaded 98 million times, making it Indonesia’s largest on-demand economy player. The company plans to invest $500 million to expand into neighboring countries such as Vietnam, Thailand, and the Philippines. Honestbee, which began selling groceries online in Singapore in 2015, offers the products of around 1,000 merchants. When a customer places an order, trained “shopper bees”—typically part-timers such as students and stay-at-home parents—purchase the items from participating stores and deliver them to the customer’s home. Now the company is expanding its concierge service to Kuala Lumpur, Jakarta, Bangkok, and Tokyo and is diversifying into laundry, travel tickets, and online payments. In a recent article in Singapore’s Business Times, honestbee’s CEO, Joel Sng, explained that the company’s scalable technology “facilitates our expansion to other parts of Asia where there is demand for our service.”

As companies’ data on consumers grows, they can create profiles of target segments across Southeast Asia. “We take a hyperlocal approach to understand what users in each Southeast Asian city prefer, from language preferences to payment options,” said Tan Hooi Ling, cofounder of Grab, a ride-hailing service. Launched in Malaysia in 2012, Grab now serves 132 cities across Southeast Asia with private cars, motorbikes, and taxis.

Chinese e-commerce giants are also investing heavily to build a footprint across Southeast Asia. For example, Tencent and JD.com—which is focusing on the region’s developing economies—have invested more than $200 million in GO-JEK. And Alibaba has invested some $4 billion in Southeast Asian marketplaces. The company already offers Chinese products in the region through its Taobao e-mall. In 2017, it invested in the Indonesian marketplace Tokopedia. And in March 2018, Alibaba boosted its stake to 83% in the Lazada Group, Southeast Asia’s largest online platform, with sites in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Significant logistical and regulatory obstacles still make it difficult to operate a seamless business across Southeast Asia. But as these issues are addressed, e-commerce companies will be able to move fast. “Once the basic operationalization in the local markets is done, it will be very fast to scale it up because the same platform will cut across all markets,” explained Aaron Tan, CEO of Carro, a Singapore-based marketplace for used cars.

Several initiatives underway in Southeast Asia could take digital integration to the next level by improving the physical infrastructure for regional e-commerce. The Malaysian government, for example, is collaborating with Alibaba to develop a Digital Free Trade Zone that it hopes will enable small and midsize enterprises (SMEs) to reach new customers overseas. A part of Alibaba’s Electronic World Trade Platform—which will provide SMEs with the commercial infrastructure for cloud computing, mobile payment, and training—the zone includes a high-tech fulfillment warehouse near Kuala Lumpur’s international airport. The free trade zone has already established a pilot program that will make thousands of products, such as fashion items, beauty aids, and home furnishings, available to shoppers in Singapore. The goal is to expand to neighboring countries.

Finally, Alibaba is collaborating through Lazada with Thai Customs and the Eastern Economic Corridor to develop a logistics hub and an e-commerce park for SMEs, service providers, and logistics partners in Thailand. The park aims to connect with the logistics infrastructure of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam and is offering e-commerce training to 30,000 SMEs.

How Companies Are Improving Their Digital Maturity

While online marketplaces are providing state-of-the-art tools for linking Southeast Asian buyers and sellers, more established companies have thus far been slow to fully introduce the latest digital technologies and practices. According to a recent study by BCG, Mindshare, and Google of “digital readiness”—a company’s capacity to leverage digital technology—62% of multinational companies in the region have only a “basic” e-commerce presence, meaning they have few products on offer through marketplaces or none at all. Only 11% of these companies have an “established” e-commerce presence that includes exclusive partnerships with marketplaces or products that are offered only online.

Our interviews with company leaders in Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines indicate that digital maturity is most advanced among financial services and telecommunications companies. The digital maturity of consumer packaged goods companies is generally more limited, particularly when it comes to using data analytics. However, our research also found that digitization is a high strategic priority among these companies. It should be noted, however, that digitization goes far beyond spending some marketing dollars on digital or selling some products in online marketplaces. It’s about how much leverage companies create through digital, how they align their online and brick-and-mortar businesses, and how they embed digital capabilities across the organization.

The more established companies have thus far been slow to fully introduce the latest digital technologies and practices.

Multinationals that offer baby and personal-care products and cosmetics, such as Unilever, FrieslandCampina, Kimberly-Clark, Procter & Gamble, and L’Oréal, are among the most successful at using digital technologies to reach more Southeast Asian consumers. FrieslandCampina, the cooperative of Dutch, German, and Belgian dairy farmers, used an effective “mobile first” marketing campaign to boost its share of Vietnam’s market for its Friso infant and toddler milk formula. Knowing that Vietnamese spend an average 78 minutes a day watching videos on their mobile devices, FrieslandCampina targeted the country’s 3.7 million mothers and pregnant woman with videos that it followed up with “buy now” text messages offering discounts. The campaign helped Friso become Vietnam’s leading premium brand for the first time, increasing its market share by 1.5 percentage points between April 2015 and April 2016.

GlaxoSmithKline is another digital leader. When sales of its Panadol pain reliever slowed in Malaysia, where it has a 90% share of the analgesics market, the company analyzed data from social media and other sources and developed 113 different consumer “pain profiles.” The analysis helped GSK identify three new segments of consumers likely to treat their pain with its product. It used the insights gained in targeted marketing campaigns that improved the perception of the Panadol brand and the return on investment from online ads.

The Next Steps Toward Digital Integration

ASEAN’s digital integration has so far been a bottom-up process—a case of many flowers blooming. It has been driven by entrepreneurship and innovation, with relatively little involvement from governments. To take integration to the next level and create a common market, several complex, shared challenges must be addressed. ASEAN’s underdeveloped regulatory framework is difficult to navigate, and different trade regimes keep many goods from moving freely across borders. Inadequate or inefficient logistical infrastructure in much of Southeast Asia also slows cross-border commerce. Yet another obstacle is the requirement that e-commerce models allow cash on delivery, since several Southeast Asian economies remain predominantly cash-based.

Southeast Asia’s private sector should work with the region’s governments and regulatory bodies to address these challenges. First, companies can help educate public officials on the powerful contribution that digital technologies and e-commerce can make to economic growth, particularly for SMEs that have had little access to other markets in Asia and around the globe.

In most companies, digital requires a shift in culture and operating model that permeates the organization.

Companies can also draw on their expertise to help governments upgrade the infrastructure needed for e-commerce and harmonize the ASEAN digital regulatory framework. Among the most urgent priorities is improving data privacy protection and standards in order to strengthen confidence in e-commerce and facilitate cross-border flows of data.

Companies should improve their ability to capture the big opportunities being created by digitization in Southeast Asia. For most of them, this will require a step-change transformation, because digital innovators such as Google, Amazon, Grab, and Netflix are setting a high bar for customer expectations that cannot be met through piecemeal innovation.

Digital transformation must be approached holistically. Many companies address it with dedicated teams in standalone departments tasked with developing a “digital strategy.” But digital is really a new way of working. It includes using data and analytics to better understand and serve customers and driving innovation through cross-functional agile teams. It is more than placing products in online marketplaces. It also requires developing unique assortments of product offerings, aligning pricing online and offline, managing channel conflicts, and fostering deep customer engagement. In most companies, these changes require a shift in culture and operating model that permeates the organization.

Companies should seek to develop an outstanding digital experience. Consumers in the digital economy value the purchase process as much as the product itself. Companies should consider running a “friction assessment” of their operations to understand issues that may be compromising the digital experience of customers and business partners.

Companies also need to enhance their ASEAN operating model to better incorporate digital. Currently, many companies still approach Southeast Asia country by country. Instead, product suppliers, retailers, and e-commerce platforms should begin to negotiate deals on a regionwide basis. Companies should also make sure that their digital capabilities are dispersed across Southeast Asia so that they can quickly scale up their regional footprint.

The economic integration of ASEAN is not a new concept. But as more companies and governments fully embrace the digital economy, that vision—and the immense rewards it can bring to Southeast Asian businesses and societies—is getting closer to being fulfilled.