T ransformation is an imperative for most companies today. In a fast-moving environment characterized by digitization, organizations face threats that emerge more rapidly—and from a wider range of competitors—than ever before. In this setting, some companies need to transform their organizations to stay on top, while others face a decline in performance and require dramatic measures to turn themselves around. In either case, transformations are extremely tough to pull off. Only about 30% of large-scale efforts succeed. No wonder the CEO job is more demanding than ever.

But some CEOs do manage to transform their companies, delivering a fundamental reboot that changes the direction of the organization and dramatically improves its operational and financial performance. These leaders seem to have captured lightning in a bottle, and BCG wanted to find out how they do it.

On the basis of a recent BCG analysis of large US companies from 2004 through 2016—and our experience with more than 750 transformation journeys across sectors globally—we have identified five defining characteristics of CEOs who succeed in transforming their companies. (For case studies, see the sidebar.)

Five Winning Transformations

The following case studies are excerpted from The Comeback Kids: Lessons from Successful Turnarounds (BCG report, December 2017).

HSBC. After a rapid expansion, HSBC launched a transformation to optimize its core business. The company reduced head count by more than 20% and the number of countries where it operated from 88 to 67. A reorganization gave HSBC a new structure with four global businesses. And the company is investing $2.1 billion in digital initiatives through 2020, including automating back-office functions and offering new digital services to customers.

Nokia. During the latest turnaround in its 150-year history, Nokia sold off its mobile handset business and instead refocused on network infrastructure. As a result, the company’s market capitalization has increased by more than 500% since July 2012, and Nokia is again a world leader.

Bristol-Myers Squibb. A decade ago, when several of its blockbuster drugs went off patent, Bristol-Myers Squibb transformed itself from a diversified health care company into a pure-play biopharma firm. It took approximately $2.5 billion out of the company (mostly through cuts in SG&A expenses) and reshaped its business units and R&D portfolios to focus on biopharma. In the past six years, the company has outperformed its peers in total shareholder return by an average of 5 percentage points per year.

Qantas. As competitors moved into its home territory, Australian airline Qantas watched its market share shrink. In response, the company launched a turnaround to reduce costs by $2.1 billion. It also revamped its fleet, streamlined maintenance procedures, shifted routes to higher-growth markets, and invested in digital technology to improve the customer experience. Since the transformation launched in 2013, profits have jumped by 500%.

Groupe PSA. Automobile manufacturer Groupe PSA—the parent company of Peugeot, Citroën, Opel, and several other brands—was struggling after the financial crisis, owing to weak demand in Europe. To counter the anemic market, the company reduced the number of models, repositioned its brands to differentiate them, and launched a pricing initiative. It also invested in digital, with programs to support its customers and better connect employees internally. The transformation returned Groupe PSA to EBIT margins in line with the industry and boosted its market cap by more than 700%.

1. They take decisive action quickly and launch formal transformation programs. When companies face disruption, some leaders have a tendency to wait it out. Long-tenured CEOs or new CEOs promoted internally—rather than hired externally—tend to wait longer and underestimate the need for change. The companies that posted the strongest transformation results took quick and deliberate action, announcing a formal transformation program within one year of a decline in total shareholder return (TSR). These firms generated short-term gains as a result of higher valuation multiples (relative to earnings) among investors, who were convinced that the companies weren’t clinging to the status quo. And in the long run, these companies showed a gain in five-year TSR of more than 5 percentage points compared with the overall sample in our analysis.

2. They unlock immediate gains to fund the journey and tell their story in the market. As initial steps in a transformation, most companies cut operational costs or take other quick actions to boost revenue or restructure the organization. Evidence shows these measures are effective in rapidly improving financial performance during the first year. But to regain the market’s confidence, leaders can’t just cut costs—they also need to tell a convincing story to investors and analysts about how the company will leverage its newly unlocked resources. These two measures—fast operational improvements and a clear story to improve valuation multiples—create confidence and free up capital that the company can use to fund the longer transformation journey.

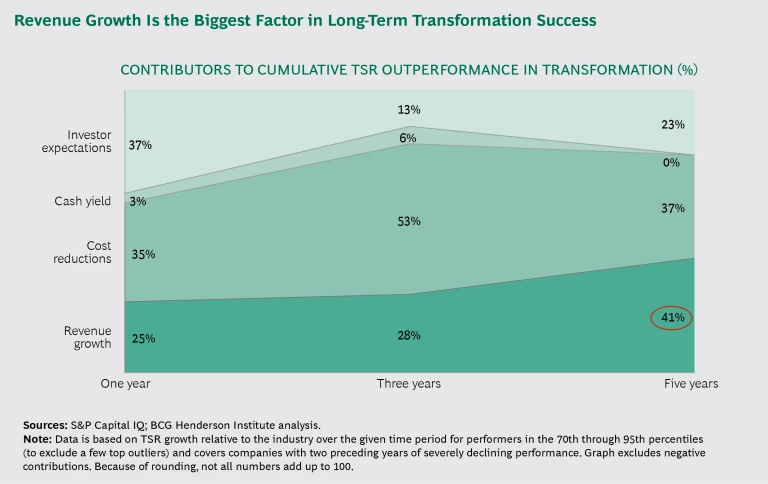

3. They include a clear second chapter in the transformation to boost growth. In years two through five of a transformation, revenue growth becomes the main driver of value creation. (See the exhibit.) Accordingly, CEOs can’t focus on short-term, operational improvements alone. They must also introduce a strategy for new growth—the second chapter in the transformation. This involves challenging the foundations of the firm’s business model, creating a fresh vision for growth—through new products, services, and value propositions—and committing to see the program through to its conclusion. It’s important that these second-chapter efforts start to show clear results in years two through five and don’t become too theoretical.

One critical aspect of this new strategy is investing in R&D with a long-term orientation, particularly for digital initiatives. These investments often have a limited short-term payoff, but they remain an important means of identifying new sources of growth. Among the transformations we analyzed, companies that spent more on R&D (as a percentage of sales) than their industry peers performed substantially better in the long run—a difference of more than 5 percentage points in five-year TSR.

Digital is an essential key to unlocking growth. Companies are increasingly using emerging technology to better understand and meet customer needs, automate and improve internal operations, and roll out new business models. But we see too many digital investments focused on back-office or support functions. Digital investments are most powerful when they directly improve customer loyalty or generate direct and quantifiable business value. (See “ A CEO’s Guide to Leading Digital Transformation ,” BCG article, May 2017.)

In contrast, capital expenditures don’t matter as much. Companies that spent more on capex performed a bit better over a five-year period, but the effect was much smaller than for, say, R&D investments. Why? Capex typically improves a company’s existing business model (such as upgrading production machinery), whereas digital or R&D investments often can identify new—and more meaningful—sources of growth.

4. They are willing to make changes to their team. In addition to their readiness to shift away from established business models, top CEOs are willing to make changes to their leadership team. We studied the executive turnover at companies immediately after a steep decline in TSR. Companies that replaced 20% or more of the officer group showed a slightly better performance in the short term and a notable improvement over the long term (an increase of more than 4 percentage points in TSR). As with business model innovation, CEOs need to be willing to put all options on the table. And because transformations are often comprehensive—and take the company into new business models and markets—it’s critical to establish a leadership team with the expertise needed to win.

5. They commit to long-term transformation programs with sufficient scope and scale. Short-term efforts do not lead to lasting success. Among firms with a formal program in place, nearly half ran their initiative for five years or more (either as one long-term program or as an unbroken series of overlapping programs). Moreover, that percentage has been growing over time, meaning we are in an era of “always on” transformation. (See A Leader’s Guide to “Always-On” Transformation , BCG Focus, November 2015.)

In addition to the timeline for transformations, our analysis looked at companies’ strategic orientation and whether they have a short-term or long-term mindset. Those with a clear long-term focus showed better results. The gains are particularly pronounced in turbulent environments, with high levels of disruption and many new market entrants.

Moreover, winning transformations also require enough capital to fund programs of the necessary scope and scale. Large programs (those involving restructuring costs of at least 2% of sales) have an especially big impact on long-term success. Compared with smaller-scale efforts, large programs delivered a 5-percentage-point gain in five-year TSR. Such long-term efforts aren’t easy—they can tax employees and management teams—but they can lead to sustained improvements in performance.

At a time when transformations are more prevalent—and more important—than ever, real quantitative evidence of what works is in short supply. The five factors identified here are an exception. Together, they provide empirical evidence that winning CEOs take decisive action to achieve successful transformations and that other leaders need to follow suit if they want to keep pace with an operating environment that gets tougher all the time.