As the private equity industry continues its run of strong performance—with solid returns, record levels of uninvested capital, and hundreds of new entrants—a growing number of sovereign wealth funds and pension funds are rethinking their traditional, passive role as limited partners (LPs). Instead, they are seeking to become principal investors, which can play a larger and more direct role in the investment process and thus claim a larger share of the gains.

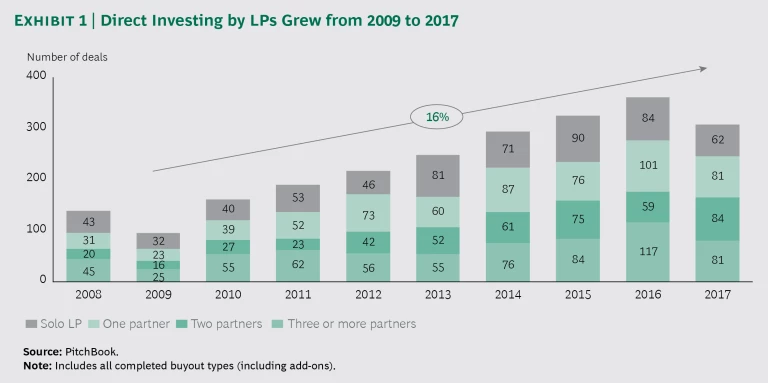

The number of deals in which these historically passive LPs invested directly grew an average of 16% per year from 2009 to 2017. (See Exhibit 1.) As a result, LPs are becoming much more comfortable taking direct stakes and are developing the capabilities needed to assume responsibility for elements of the investment process that PE firms once handled exclusively.

But going it alone is not without risks—primarily in the form of stiff competition from the leading PE firms. Over the past ten years, these have established a clear track record of top-quartile results across multiple funds. Leading firms have deep functional and industry expertise, and they have become highly sophisticated in how they source deals, create value, and exit investments. LPs that try to compete against PE firms without the right capabilities will fail.

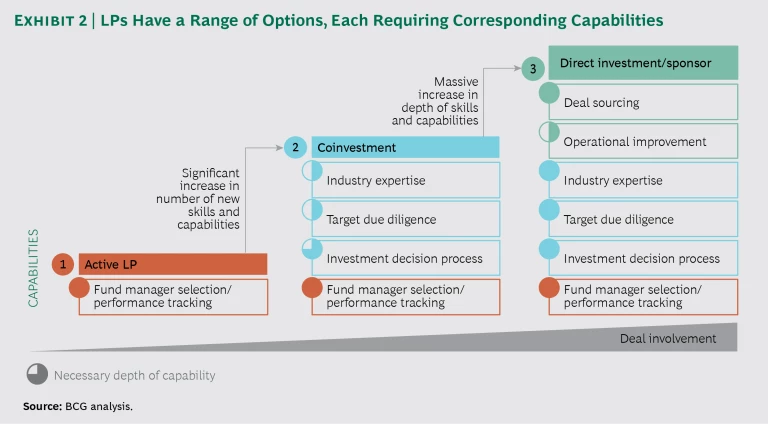

LPs that are considering direct investments have a range of options. Some may choose to begin making their own direct investments, while others may opt to become a preferred partner for coinvestment opportunities—or just become more engaged LPs. All these options have a consistent theme: LPs are willing to expand their traditional roles in PE and invest in the right operating model to improve their financial performance.

Three Ways That LPs Are Adapting

For LPs that want to take on a bigger role in the process, there is a logical sequence of options, each increasingly complex and involving more required capabilities. (See Exhibit 2.)

Become A More Engaged Traditional LP

The first approach—and the most straightforward—is to continue to invest through traditional PE funds while taking steps to become a more engaged customer. This includes consolidating relationships with a smaller number of PE firms. Large LPs can have investments spread across hundreds of firms, making it hard to engage, monitor, and exercise negotiating power with their PE firm partners. Reducing investments to a more manageable number of firms gives LPs a better seat at the table when decisions are being made about how their money is invested.

The California Public Employees’ Retirement System, for example, has been highly public about its goal of consolidating its relationships with PE firms as a first step toward ultimately buidling and running its own direct private equity program. This process could take decades, but becoming a more engaged traditional LP is the organization’s initial move in that direction.

Become A Preferred Partner for Coinvestment Opportunities

The second approach is to develop capabilities that will allow LPs to seek out coinvestment opportunities from PE firms.

For LPs, coinvestment is an intermediate step that places them further up the PE value chain, while still letting established firms handle the bulk of the processes, such as sourcing deals, short-listing investment opportunities, and actively managing investments in the portfolio. In some cases, LP coinvestors are able to negotiate seats on the boards of portfolio companies, which gives them greater visibility into the practices of the PE firm and allows them to learn from the value creation model of large firms firsthand.

Roughly 90% of LP investors report that returns from their coinvestments match or outperform their PE fund investments.

To pursue coinvestment opportunities, LPs need to streamline their governance processes to enable extremely rapid go/no-go decisions on investments that potentially involve larger pools of capital than those involved in traditional, passive investments. They also need to build up capabilities such as due diligence and industry expertise. (See “Five Ways LPs Can Become Attractive Coinvestment Partners.”)

Five Ways LPs Can Become Attractive Coinvestment Partners

Five Ways LPs Can Become Attractive Coinvestment Partners

Coinvestment is a more direct partnership than traditional private equity investments, and LPs need to position themselves as the right choice for PE firms. Our experience—and interviews with leading firms and CEOs of PE-owned companies—suggests that taking the following five measures can help:

- Hire the right team. Focus on people with strong professional networks and hands-on deal experience. They can typically be found either at PE firms or at investment banks that have a proven track record and the same mindset as established PE firms.

- Streamline the investment approval process. Design a process that mirrors the demands of partner firms and accommodates the reality of the deal process (which frequently requires rapid yes or no decisions involving significant capital).

- Invest in quality firm relationships. Be strategic and selective about the funds you choose to partner with so that employees can forge deeper relationships with a smaller set of players. Be transparent about your firm’s key objectives—strategy, expected returns, and investment profile—when considering coinvestments. The goal is to find a coinvestment partner, rather than a traditional fund manager.

- Increase your profile in the market. Ensure that your deal team gets prominently covered in the media, including its experience and capabilities working with PE firms.

- Go direct without encroaching on the space of your trusted PE partners. Identify sectors and geographies where your priority PE firms focus their efforts and refrain from investing in those areas.

The coinvestment structure can be particularly challenging for PE firms because it puts downward pressure on their bottom line. In addition, coinvestment adds a layer of unpredictability to the deal process in terms of both timing (LPs need to make decisions quickly) and the final investment amount (firms often don’t know how much LPs will actually be able to invest until late in the process). And coinvestment increases the complexity of firm operations, in that it requires new processes such as distributing coinvestment gains to LPs and collaborating more directly with LPs to improve the performance of portfolio assets. In some cases—most commonly with sovereign wealth funds—coinvestment partners require firms to train their people on the investment process itself.

These considerations aside, coinvestment is still attractive to some PE firms because it allows them to seek large-scale deals that they would otherwise not be able to pursue with a single fund. Some firms are even taking hybrid approaches to accessing capital for multiple future deals through a single LP. (See “A Hybrid Approach: Acting as the Anchor Investor.”)

A Hybrid Approach: Acting as the Anchor Investor

A Hybrid Approach: Acting as the Anchor Investor

Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia (Saudi PIF) is using a hybrid of coinvestment and direct investment in which it commits a predetermined platform of capital to a specific fund and then serves as an anchor investor. Notable examples are its commitment of $45 billion to the SoftBank Vision Fund, representing nearly half the fund’s $93 billion in total capital; more recently, Saudi PIF committed $20 billion to Blackstone’s $40 billion infrastructure fund.

This approach gives transparency to the fund managers—in that they know they will have access to a set amount of capital—while still allowing LPs to approve individual investments on a deal-by-deal basis.

With this approach, Saudi PIF is able to act as a principal investor with the right (but not the obligation) to invest in a deal, and it can undertake its own due diligence and play a strong role in governance and value creation for portfolio companies. It is not seen or structured like a single convestment, but rather as an advance commitment across several deals. LPs that adopt this approach need to develop much deeper industry and transaction expertise than a coinvestment arrangement requires.

Become A Direct PE Investor

The third option—and the one requiring the most advanced capabilities—is to develop a separate, in-house investing team that enables LPs to make direct PE investments. This is the option that provides the greatest autonomy—the LP can precisely match investments to its risk tolerance and return objectives—as well as the lowest cost (since LPs save the fees paid to general partners). Some LPs that take this approach have sought to create an investment platform in a single industry, such as real estate or infrastructure, allowing them to build up their expertise in a narrower area and apply value creation strategies across multiple portfolio companies.

A number of sophisticated and well-established LPs have applied this strategy, including several Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds and most of the major Canadian pension funds.

Challenges in Going Direct

Although LPs are starting to develop their own direct-investing capabilities, they have done few deals on their own. Just 62 of more than 300 direct deals done by LPs in 2017 were solo deals. In a market crowded with sophisticated PE investors, it is hard to source deals at attractive valuations. In addition, many traditional LPs looking to go direct face internal approval challenges and regulatory limits on equity ownership.

Moreover, direct investment represents a major shift in the organization and operations of most LPs. Success requires that the LP fundamentally change the way it makes decisions and—critically—how it thinks about risk. When investments are through a PE firm, the latter takes on most of the risk: performance risk, operational and market risks, and reputational risk. Many of these risks revert to the LP once it makes PE investments directly.

Another consideration for active LPs is the risk of stakeholders pressuring them to participate in politically motivated deals that are not always optimal from a performance standpoint.

Direct investment represents a major shift in the organization and operations of most LPs.

Talent is a critical consideration as well. As the PE industry continues to grow and new firms launch, the competition for top people is becoming fierce. It is challenging enough for pension funds and sovereign wealth funds to create good teams in traditional functions; creating a world-class direct-investing team—one that can make direct investments and manage portfolio assets to improve performance—is even harder, especially if funds don’t yet have the scale to justify the deep vertical and functional expertise required. In addition, many industry professionals have remarked that LPs have significantly higher turnover than PE firms, exacerbating the lack of sufficient internal expertise for direct deals. This is also an issue at portfolio companies, where excessive turnover at the board level can result in LPs losing their voice at the table.

There are organizational issues as well. Direct investing requires two “classes” of employees, with a potentially large difference in compensation. Fund managers, analysts, and other talent at top PE firms are well compensated, and paying them PE-level salaries at, say, a public pension fund would likely raise eyebrows—among outsiders but also among other investment professionals in the organization.

Reporting practices can exacerbate the problems with compensation. While there are variations by geography, many LPs are currently required to report only net returns, so the fees that they pay to PE firms are hidden from the public. When an LP is building its direct-investing program, the savings on those fees are not seen in its reporting, but salaries and other forms of compensation paid to employees are public, inviting further scrutiny.

All these factors create new risks for LPs. Some members of the public may demand transparency regarding the investment criteria—or the investments themselves. Many principal investors typically don’t want to be seen as agitating for operational improvements, especially in situations that call for headcount reductions. Very often, they prefer to partner with PE companies, which will be the face of such value creation campaigns.

LPs could also threaten their relationships with PE firms by going direct, especially in cases where they are competing for deals. That could potentially affect LPs’ ability to invest in future PE funds through traditional channels. (Some LPs have avoided such conflicts by creating “no-fly zones”—areas in which they do not compete against PE firms with which they have an ongoing relationship.)

Direct investing is not for the faint of heart. It requires redesigning the organization and making significant investments to build capabilities. Yet in the current PE market, direct investing should be a consideration for virtually all pension funds and sovereign wealth funds. The case in favor is clear: greater control over investments, potentially lower cost, more transparency, and a better seat at the table to drive value. Moreover, there is a spectrum of options, from being a more engaged traditional investor to building a separate internal team to make direct investments. Funds that make the right choice for their needs—and build the capabilities to support that model—will succeed.