The technologies of the defense industry are in the early stages of a seismic shift: artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics are changing defense now and will enable intelligent warfare in the decades to come. These technologies will have a correspondingly tectonic effect on defense contractors. In the near term, incorporating AI into the design of traditional battle networks will vastly improve performance of current platforms and forces. Prime contractors will maintain an advantage during this phase. However, as the capabilities of AI and robotics reach an inflection point, the US Department of Defense (DoD) will shift to smaller AI- and robotics-based systems—and will rely on nontraditional players to provide them.

Thus far, many established defense contractors have treated AI and robotics as ancillary markets. But they have underestimated the long-term threat to their business. AI and robotics specialists are bringing step change improvements to legacy systems and are building scale, know-how, and trust within the DoD. For now, they are primarily working through traditional contractors. But as trust in independent autonomous systems grows, the contractors that provide them will also gain trust—and share.

Although the full impact of the AI- and robotics-driven revolution is a decade or more away, it is clear that these technologies will radically disrupt the defense industry. How should defense contractors respond? We believe that they should take the lead in AI and robotics, making the strategic changes and investments necessary to win in these emerging segments.

AI and Robotics Will Transform Military Operations

The US military has enjoyed superior conventional forces since the end of the Cold War, but this lead has narrowed in recent years. For example, several countries have developed “anti-access” technologies, such as long-range air defense systems and precision strike weapons that deny US military forces the ability to operate in a contested area. And these same countries are actively developing AI and robotics to further close the gap.

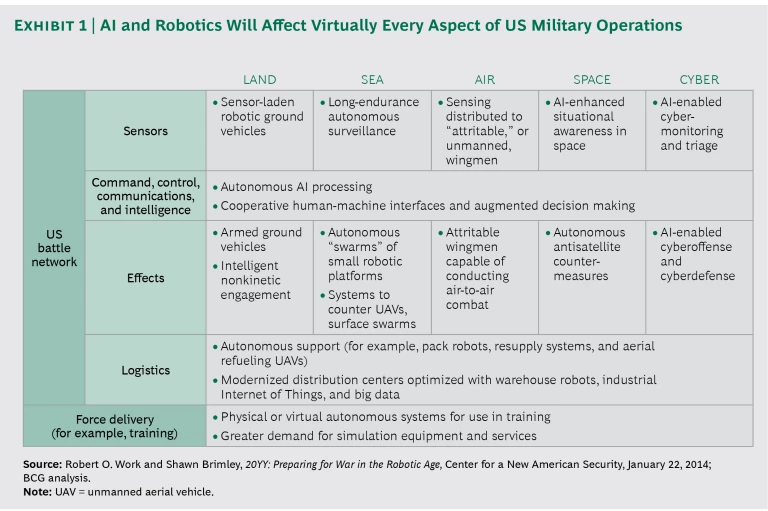

To offset those countries’ recent gains, the DoD has developed a multidecade strategy for applying a suite of advanced technologies to nearly every facet of its operations. (See Exhibit 1.) In the first phase, the DoD will create a more intelligent force, using AI to enhance platforms, munitions, and decision processes. As these technologies mature, the DoD aims to create a more autonomous force, pairing AI-enabled systems with human military personnel to accentuate the strengths of each, enabling faster decisions and better combat outcomes. In the more distant future, “swarms” of advanced cognitive robots may redefine combat operations in the battle space.

However, the DoD’s approach to AI and robotics needs to be different from previous military technological innovations, many of which had development cycles that were measured in years or—for complex platforms—even decades. In that environment, there were only a few established contractors that could realistically compete for contracts. Today, by contrast, the DoD is bringing in key technologies from commercial industry, increasing the scope of competition that prime contractors face.

For example, the DoD created the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental, or DIUx, a venture arm that uses a faster and more straightforward process to award contracts to promising early-stage commercial ventures. And the DoD is streamlining its acquisition structures. Each branch of the US military services now has—or is developing—a Rapid Capabilities Office that aims to get new technologies into the hands of military personnel more quickly than the traditional procurement process. The 2017 National Defense Authorization Act accelerates these initiatives, reorganizing the DoD office responsible for acquisitions so that the DoD can experiment with commercial technologies, adapt fielded systems with new technologies, and shorten development cycles. The logic behind these investments is clear: the DoD is seeking to cultivate a robust and diverse mix of AI and robotics firms in order to access these critical technologies.

The Threat to Prime Contractors

Thus far, prime contractors have been underestimating the risk to their business, especially because the change does not yet seem dramatic. In the near term, the military and its acquisitions function will operate much as they have in the past. The DoD will not seek to immediately replace today’s platforms; instead, it will enhance them with AI. New incremental investment will favor AI and robotics applications, but near-term spending on platforms will remain stable.

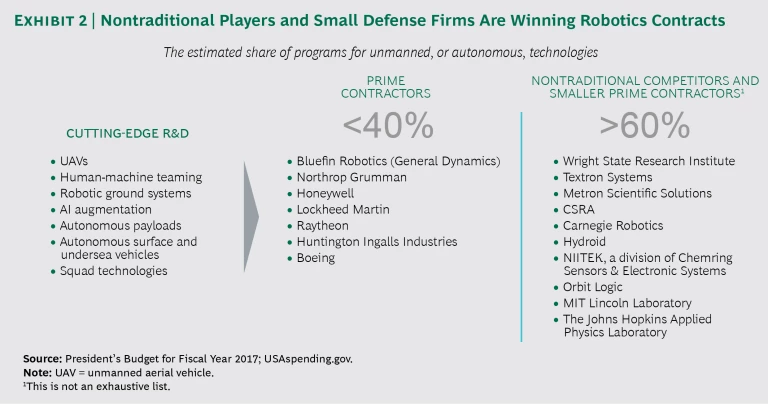

In this environment, prime contractors will maintain their preeminent positions as the gatekeepers to major DoD programs, and these contractors may be tempted to cede the AI and robotics market to small niche players or subcontractors. We see this happening already: more than 60% of the robotics-focused contracts in the President’s Budget for Fiscal Year 2017 were awarded to nontraditional defense players or small prime contractors. (See Exhibit 2.)

Still, prime contractors risk missing the next generation of defense spending. In the next wave, a decade or more away, DoD investment will target a significantly autonomous force. The transition will begin as AI and robotics mature and the DoD pairs robotic systems with human warfighters. In this phase, acquisition priorities will shift: the DoD will look to autonomous systems to perform a wider range of missions. There will be fewer traditional platforms, and they will be more general-purpose, satisfying future mission requirements with specialized AI-enabled payloads and more frequent digital—rather than physical—upgrades. The winners in this phase will be the contractors that built early leads in AI and robotics, and the prime contractors that did not prepare for this future risk will lose market share.

This phenomenon, called “segment retreat,” is a common pitfall that challenges industries in which market leaders with significant experience face new entrants and choose not to compete against them in noncore segments. Prime contractors risk making this mistake as sales of current platforms decline, acquisition processes evolve, and new competitors—better equipped to meet the military’s changing needs—emerge. The experience and scale advantages that prime contractors worked so hard to establish will erode, and the fixed costs that support those large platforms will be stranded, leading to a kind of death spiral. As platform unit costs rise, the DoD will further reduce its spending on those platforms.

Lessons from Other Industries

There are many examples of incumbents retreating to their core products in the face of change. The classic example is the British motorcycle industry. In the 1970s, British manufacturers such as Triumph dominated the market. When Honda emerged as a threat in the light-motorcycle segment, Triumph abandoned that segment as noncore. Honda focused on increasing sales volume (rather than short-term profitability), building scale, and reducing its costs through experience. It ultimately attacked and displaced Triumph in the core, heavy-motorcycle segment as well. From 1968 through 1975, British manufacturers’ global market share fell from 55% to just 4%.

In pharmaceuticals, by contrast, incumbents have been able to avoid this trap. During the early years of this century, the patents on a string of blockbuster drugs expired, threatening revenues. Worse, when innovation shifted and universities and startups dominated early-stage R&D in a new category of drugs known as large-molecule biologics, the incumbents’ internal laboratories were unable to refill the pipeline. The new technology blunted the traditional advantages of large companies.

Unlike British motorcycle manufacturers, the established pharmaceutical companies recognized the threat and took deliberate steps to address it. They aggressively licensed promising products, acquired pipelines of new drugs through M&A, and struck alliances and partnerships with specialty firms and academic institutions. To capitalize on emerging innovations, the big companies focused on their core commercial strengths: getting new products through trials and into the market and boosting sales through strong sales-and-marketing capabilities. From 2005 through 2016, the five largest pharmaceutical companies successfully avoided disruption, preserved their core competitive advantage, and increased revenues.

Moving Beyond Business as Usual

Prime defense contractors have taken initial steps to avoid disruption. Over the past 18 months, they have conducted several high-profile robotics-related acquisitions. Contractors have also expanded their venture capital arms and have begun partnering with and investing more in startups. Still others, positioning themselves as bridges between the DoD and Silicon Valley, are beginning to embrace AI and robotics companies as key subcontractors.

These moves are, however, incremental—not transformative. The DoD is taking deliberate steps to court nontraditional defense companies, cutting traditional contractors out of the loop. To win in AI and robotics in the long term, these contractors must shed their old operating models, which are built for large long-duration programs, and instead apply the kind of agile development processes that robotics programs require. They also need to rapidly incorporate technology from commercial industry.

To that end, traditional contractors do have significant advantages. They have a deep understanding of defense missions and threats, and they can access data to “train” and improve AI systems. In addition, established contractors have the resources and financial strength to make critical investments. Still, to move beyond business as usual, they need to take more committed action in a number of areas, focusing on the following imperatives:

- Establish innovative units with separate cost structures. Contractors need standalone units that can operate with the innovation, speed, and cost structures that competing in AI and robotics requires. Burdening these units with legacy overhead costs or focusing on near-term profitability guarantees that they will fail to achieve scale.

- Invest in key enablers with a particular focus on data. Invest in key technology building blocks, especially those that can create durable advantages. For example, contractors should maintain proprietary data to train the AI engines that power robotic systems.

- Scour the world for new technologies, and access them creatively. Defense contractors need to partner with leading AI and robotics companies, especially in industries such as automotive that require high levels of spending.

- Fully embed agile to accelerate innovation in both software and hardware. To stay ahead of global threats, the DoD requires speed. (See "How the Defense Department Can Apply Agile Thinking to Acquisitions.") Contractors must, therefore, accelerate development cycles dramatically.

How the Defense Department Can Apply Agile Thinking to Acquisitions

How the Defense Department Can Apply Agile Thinking to Acquisitions

This article focuses on defense contractors, but the DoD itself faces disruption risk. The department is making some of the right moves, but its primary focus remains on conventional capabilities and traditional acquisition approaches. The DoD should take specific steps to spur agile development among suppliers.

- Issue bids that are based on mission requirements—not technical specifications. Rather than eliminating contractors with highly detailed specs at the outset, allow contractors to bring their best and most creative solutions.

- Get minimum viable products and beta versions of platforms into the field quickly. Instead of trying to acquire products that are perfected in the design and testing stage, the goal should be speed—getting “good enough” products into operational use, testing them under real-world conditions, and improving them iteratively on the basis of feedback.

- Shorten the time between upgrade cycles. The days of decades-long programs are over. Today, the Pentagon needs to encourage upgrades and improvements on an ongoing basis.

- Actively invest in key enablers of robotics and AI. Data will be a key differentiator, and the DoD has to build the data infrastructure to both gather and use the vast amounts of data that sensor-laden robotic systems generate. Moreover, the DoD has to apply advanced AI to sift through and manage data in order to ensure that the cost of data processing does not overwhelm the military’s ability to operate. Furthermore, the DoD has to build standardized and scalable databases with the right access structure so that data can be used to train AI-enabled robotic systems.

- Keep legacy platforms relevant and affordable by improving interoperability. AI augmentation, new robotic systems, and rising costs will pressure existing platforms. Contractors can keep these platforms relevant by ensuring that they can become progressively more intelligent and work alongside new robotic systems. In addition, contractors can control costs and build experience by developing modular, customizable systems that are based on common building blocks.

- Be willing to compete against your own legacy platform businesses with small robotic solutions. Robotics can lead to innovative solutions that render companies’ legacy platforms—even the dominant cash cows that contractors have long benefited from—obsolete. This should not stop companies from developing and offering innovative solutions: if they do not, other players will.

- Focus less on reliability and more on system performance and cost. As the DoD develops applications for “attritable,” or unmanned, and swarming robotic systems, 100% reliability and high performance lose importance. Missions call instead for low-cost tools that are inexpensive enough to deploy in volume. This shift will have cascading consequences for low-tier suppliers that will also need to apply less stringent standards for performance and reliability for the parts and components they produce. (And as a result, suppliers will no longer be able to build their businesses around their certification for large programs, potentially leading to more turnover in the contractor supply base.)

Robotics and AI technologies are on the brink of reshaping defense, and the DoD is relying more and more on technologies from commercial players outside the defense industry. Without deliberate moves to compete in the emerging AI and robotics spaces, traditional defense contractors face a downward spiral of disruption and declining relevance. The good news is that, in terms of market insights and data, traditional contractors should have a structural advantage over new entrants. But to avoid segment retreat and win in these emerging markets, they need to take deliberate steps to capitalize on their advantages, starting today. The nature of combat is evolving. Defense contractors must evolve as well.