It has been a tumultuous year for global manufacturing. Tariff wars, renegotiations of decades-old trade treaties, and the prospect of Brexit—all of which threaten to disrupt long-established, well-oiled global supply chains—have dominated the headlines. But a less-noticed change in the global business environment also has important implications for where the world’s goods are produced: a significant shift in the relative cost competitiveness of the world’s leading manufacturing economies.

Sharp swings in labor and energy costs, as well as in currency exchange rates, over the past few years have flattened some of the global differences in cost competitiveness, underscoring the need for companies to take a fresh look at their global manufacturing strategies. The cost advantage that the US has enjoyed over Japan and several European countries has recently narrowed, for example, while China’s cost competitiveness has improved. Some of the lowest- cost manufacturing nations, such as Mexico, Thailand, and Ireland, meanwhile, are dispersed around the world.

Our analysis of short-term cost fluctuations and longer-term trends supports a view we have held for several years: rather than concentrating production in a handful of “low-cost” developing economies to serve world markets, companies should adopt a more flexible, regional approach to their global manufacturing footprints and supply chains. (See The Shifting Economics of Global Manufacturing: How Competitiveness Is Changing Worldwide , BCG report, August 2014.)

While the availability of cheap labor used to be the most important consideration in manufacturing footprint decisions, other factors such as energy and logistics costs have become increasingly important when assessing the total cost of production. These “secondary” factors will matter even more as companies increasingly deploy advanced manufacturing technologies, many of which are designed to eliminate labor from production processes. The imperatives of reduced time to market and more flexibility to respond to customer needs will further push firms to more regional sourcing and production.

Factors other than the availability of cheap labor have become increasingly important in manufacturing footprint decisions.

Cost Advantages Narrow

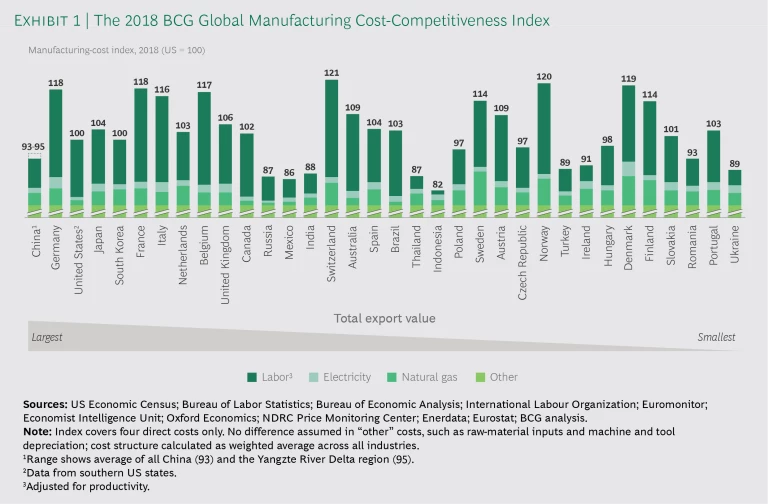

The US has experienced some of the sharpest swings in competitiveness. From the early 2000s to 2015, US cost competitiveness improved markedly against major manufacturing economies in Asia and Europe, according to the BCG Global Manufacturing Cost-Competitiveness Index, which tracks changes in relative factory wages, productivity growth, currency exchange rates, and energy costs. (See Exhibit 1.)

Since 2015, however, the US has lost competitiveness against 31 of the 34 countries in the index. The chief reasons are strong gains by the dollar over other major currencies, factory wages that have been rising faster than manufacturing productivity growth, and a declining energy-cost advantage as gaps in global energy prices narrow.

To be sure, the US is still among the most cost competitive of the world’s major global manufacturing nations: of the top ten goods-exporting countries, only China is cheaper, on average. But other economies are catching up. For example, direct manufacturing costs in the UK were 15 percentage points higher than those in the US in 2015; that gap has since narrowed to 6 points.

The US is still among the most cost competitive for manufacturing, but other countries are catching up.

China, the world’s biggest exporter, has also seen significant change. A once-enormous cost advantage over the US and other leading industrial economies had been eroding for years, largely because of double-digit annual increases in wages that far outpaced productivity growth, a strengthening currency, and relatively high energy costs. By 2016, China’s cost advantage over the US had narrowed to only 2 to 4 percentage points, depending on the region, before factoring in transportation and logistics costs.

China’s resilience has been equally notable, however. Over the past two years, China’s cost advantage has widened again, to 5 percentage points over the US for the Yangtze River Delta and 7 points for China as a whole. This shift has been driven largely by a weakening yuan, falling energy costs, and the movement of production away from relatively expensive coastal provinces. With its unmatched scale, immense internal market, heavy investments in automation, well-developed supply chains, and steady advances in technology-intensive industries, China very much remains the world’s workshop—and will likely hold on to that position for the foreseeable future. (See the upcoming BCG article “China’s Next Leap in Manufacturing,” December 2018.)

Relative declines in productivity-adjusted labor costs have also helped several European countries, such as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, regain competitive ground. Since 2014, labor costs in France and Germany have fallen by around 10% relative to the US. They have also dropped in the UK, largely because of the 15% decline in the pound relative to the dollar. Moderate productivity growth—6% in Germany and 10% in the UK—has also strengthened manufacturing competitiveness. Manufacturers in several East Asian nations, meanwhile, have benefitted from falling energy costs. In Japan, for example, electricity costs have declined by around 13% since 2014, while prices for industrial natural gas—once among the world’s highest—have fallen by nearly half.

Against the backdrop of these changes, ongoing global trade disputes highlight further potential risks for manufacturers. It is our view that these disputes are likely to persist, which only underlines the strategic importance of taking a look at current exposures and long-term supply chain and manufacturing strategies.

Relative declines in productivity-adjusted labor costs have helped several European countries regain competitive ground.

Behind the Swings in Cost Competitiveness

The changes in relative cost competitiveness around the world are driven by multiple factors.

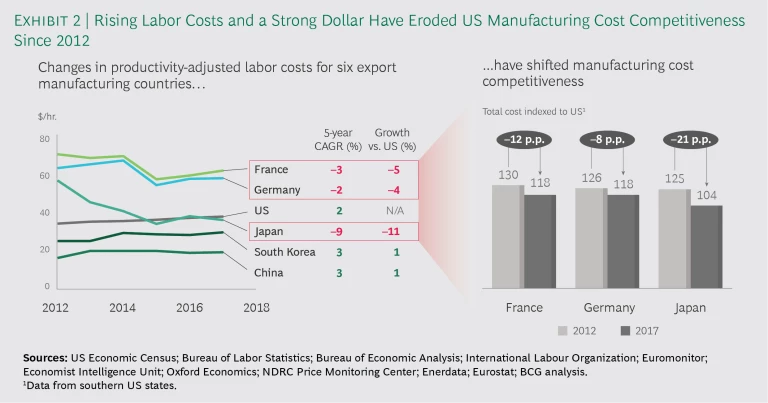

Productivity-Adjusted Labor Costs. US manufacturing wages have been rising by 2% a year on average since 2012. Rising wages, after many years of stagnation, are good news for US workers. The bad news is that manufacturing productivity gains have not kept pace, increasing by less than 1% over the same period. That means productivity-adjusted labor costs for manufacturers operating in the US have been rising by 2% a year. In Germany, by contrast, productivity has risen in parallel with the US, but wages have remained flat. As a result, Germany’s productivity-adjusted labor costs have fallen by approximately 2% since 2012; these differences contribute to Germany’s 8 percentage-point gain over the US in the index. In Japan, productivity increases and falling labor costs have helped drive productivity-adjusted labor costs from nearly $60 an hour in 2012 to less than $40—leading to a 21-point gain in overall cost competitiveness relative to the US from 2012 to 2017. (See Exhibit 2.)

Exchange Rates. The US economic recovery since 2010—a period when other regions experienced some instability—has enabled the dollar to strengthen against key currencies. That has made US goods more expensive abroad, and imports cheaper. The dollar has gained 4% against the yuan and 8% against the Mexican peso since 2015, for example.

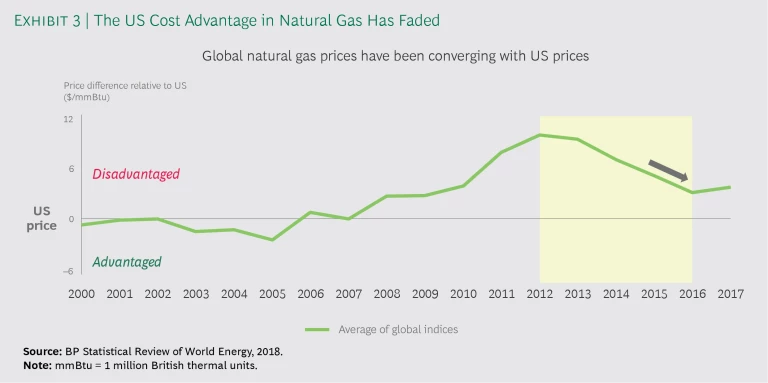

Energy Costs. The dramatic expansion of energy production from shale in the US and Canada since 2004 resulted in a sharp decline in North American prices for natural gas—a key input in industries such as chemicals and plastics—as well as for industrial electricity. At the same time, natural gas prices spiked in other economies. In 2012, for example, natural gas was around three to four times more expensive in Europe than in North America and nearly six times more expensive in much of Asia. This gave North American manufacturers in energy-intensive industries a significant cost advantage. Since then, that advantage has narrowed considerably as a result of higher North American gas exports and the expiration of old gas-supply contracts elsewhere. (See Exhibit 3.)

Material and Indirect Costs. The BCG index assumes that material and indirect costs—which typically account for 75% to 80% of the cost of a finished product—are basically consistent around the world. However, recent duties imposed by the US on imported steel and aluminum and on a wide range of Chinese products—as well as retaliatory tariffs assessed by US trading partners—will affect the competitiveness both of US-based manufacturers and those that export to the US. In addition, the US, Canada, and Mexico have renegotiated their trade rules. The BCG index does not take into account such indirect costs, and it is too early to assess the overall impact of new trade rules on each nation’s cost competitiveness. While these actions will benefit employment in some US manufacturing sectors, they will negatively affect others. In a free trade model, protectionism tends to weaken a nation’s global competitiveness.

Several developments have been favorable for US manufacturers. In 2017, for example, Congress slashed the corporate tax rate—once one of the highest in the industrialized world—from 40% to 27%, below the levels of nations such as Japan, France, and Germany. The federal government has also rolled back financial industry regulations and has issued few new regulations for nonfinancial businesses. Partly as a result, the US rose from eighth place to sixth in the World Bank’s annual “ease of doing business” rankings in 2018. While these actions should benefit US manufacturing, most studies to date have found limited impact on investment.

Adapting to the Shifting Manufacturing Landscape

The shifts identified in our 2018 cost-competiveness index underscore the imperative for manufacturers to build flexible organizations and supply chains that can adapt to a global climate of continued volatility and changing trade regimes. (See “Navigating the New Geopolitical and Trade Environment.”)

Navigating the New Geopolitical and Trade Environment

Navigating the New Geopolitical and Trade Environment

The BCG Global Manufacturing Cost-Competitiveness Index tracks changes in the costs of specific production inputs, which are measurable and generally easy to quantify. But companies need to take other factors into account when assessing the relative competitiveness of production locations. Trade policies and geopolitics, for example, also influence the global economics of manufacturing—and can pose risks.

Tariff wars have recently broken out among several major trading economies. In the spring of 2018, for example, the US imposed tariffs of 10% on imported aluminum and 25% on steel. Canada, the EU, Mexico, and other trading partners retaliated with their own tariffs on US aluminum and steel, as well as on other US products. The US and China are currently applying tariffs of 10% to 25% on some $300 billion in bilateral trade. Companies that lack flexible sourcing, production, and distribution may face significant operational and financial risk in this environment.

Countries have also been resorting increasingly to nontariff barriers that restrict trade. These can range from administrative friction at border crossings to preventing imported goods from crossing a border for allegedly failing to meet domestic regulatory requirements.

There have also been some trade-liberalizing measures in recent years, such as the signing of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership among 11 Pacific Rim nations. However, Global Trade Alert reports that restrictive measures have outpaced liberalizing measures by almost two to one. History has shown that countries targeted by trade barriers tend to respond with barriers of their own, and that breaking such a cycle can be difficult.

Companies need to assess their upstream networks, manufacturing networks, and downstream networks in order to fully comprehend the risks and opportunities that come with an unstable global environment. (See “ How to Thrive in an Era of Shifting Trade Policy,” BCG article, June 2017.) To assess relative risks, companies should examine not only their own value chains but also those of their key competitors.

Trade barriers are certain to be a fact of life in a global environment of increasing economic nationalism and state capitalism. Companies with flexible value chains and sound contingency plans will be more resilient in the face of a changing geopolitical and trade policy landscape.

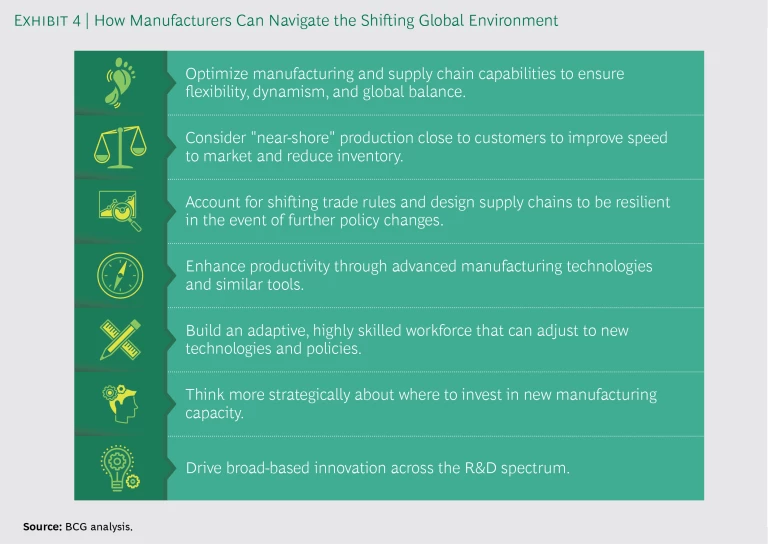

We see seven key actions that global manufacturers should take. (See Exhibit 4.)

- Optimize manufacturing footprints and supply chains. Manufacturers should evaluate the global distribution of their existing and future customer base. They should then ensure that their manufacturing operations and supplier networks are flexible, dynamic, and globally balanced enough to serve those customers.

- Consider near-shore production. Companies should carefully weigh the potential advantages of manufacturing close to customers, as opposed to producing in distant offshore locations. A holistic analysis of all supply costs may find that the savings on labor from manufacturing offshore may be offset by the ability to more rapidly reach markets, replenish inventory, develop product prototypes, and implement design changes.

- Account for shifting trade rules. Manufacturers should design their supply chains so that they are better able to shift production and sourcing in the event of further shifts in trade regimes and instability in policies and exchange rates.

- Focus on productivity. Efficiency and output per worker are the primary battlegrounds of manufacturing competitiveness. The real productivity contest, however, is between companies rather than countries. In China, for example, we see many modern factories belonging to multinationals as well as domestic manufacturers that are more efficient than their Western rivals. Companies should continue to make progress with lean manufacturing and explore advanced manufacturing technologies, such as flexible robots and advanced automation, and aggressively pursue other opportunities to lower costs and increase output.

- Build an adaptive, highly skilled workforce. As factories adopt advanced manufacturing technologies—and trade regimes continue to shift—demand will grow for highly skilled workers who can adapt to change. Companies need to build these workforces through recruiting, training, and collaborating with educational institutions. (See “ Building an Adaptive US Manufacturing Workforce ,” BCG article, September 2017.)

- Think more strategically about investment in manufacturing capacity. Decisions about where to build new factories will affect a company’s global competitiveness for decades. When considering locations, companies must take into account not only current cost structures but also how they could evolve.

- Drive broad-based innovation. As factor costs such as labor and energy approach global parity, manufacturers around the world will compete more on innovation. Companies must not only focus on innovative design but also remain engaged across the R&D spectrum. This will require collaboration with university researchers to translate technological advances into new factory processes and breakthrough products.

Success in today’s global manufacturing landscape requires the flexibility to respond to, and capitalize on, near-term disruptions. It also requires the patience to invest in durable sources of competitive advantage. While volatility and trade wars will continue to dominate the headlines, prudent investors should keep an eye on the long term, secular trends that ultimately determine global cost competitiveness.