It goes without saying that quality is a key competitive factor in every industry. To provide high-quality products and services means to fulfill explicit and implicit customer expectations, along every step of the value chain: R&D, procurement, production, sales and distribution, and after-sales service. Problems with quality translate quickly to lower levels of customer satisfaction, higher costs, and shrinking revenues.

Over the past 20 years, most companies have invested heavily in quality improvement—including quality management systems, quality processes, and IT systems—aiming to secure and consistently improve the quality of their operations. Despite the marked improvements that have come from these efforts, however, recalls due to quality deficiencies are still common, costing companies billions of dollars. Without a transformation within an organization’s culture , quality management will continue to suffer.

The Road to Quality Defects

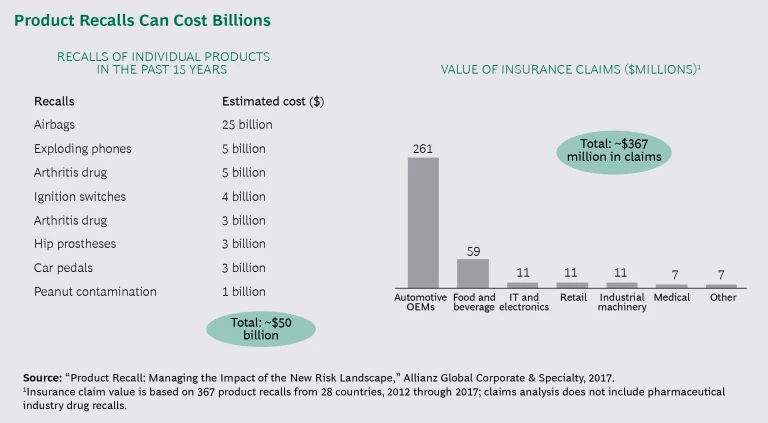

Notable examples of recalls from the past 15 years include artificial hip joints, arthritis drugs, car ignitions, car pedals, airbags, and exploding battery packs in mobile phones—adding up to $50 billion in losses. According to insurance records, the auto industry has claimed the highest costs, followed by the food and beverage industry. (See Exhibit 1.)

What leads to these significant quality defects? Here are three examples:

- Failing to Follow Instructions. At an automotive OEM, superiors and forepersons frequently considered simple operating instructions to be secondary to the work at hand. Management only addressed the quality issue when significant quality problems arose, leading to increasing costs to remedy those problems.

- Pushing for Innovation over Quality. A consumer electronics company focused almost exclusively on securing innovations within the shortest possible development time. Leaders offered incentives to R&D employees, but there were no rewards for ensuring sustainable quality. As a result, people would push products to their limits for the sake of innovation, incurring risks without really understanding them. Systematic risk assessments were severely lacking, and the result was a growing number of complaints and a drastic rise in warranty costs.

- Solving Problems on the Surface. Instead of conducting analyses of the systematic root causes of customer issues, an engineered-products company rewarded the fast, short-term elimination of these problems. There was no attention paid to the upstream processes, such as development, production, and procurement. The result was that the same mistakes were repeatedly made, customer satisfaction dropped, and error costs rose.

To Change Behavior, Change the Context

On the whole, people tend to behave rationally and are influenced by the behavior of others; seldom does anyone intentionally act to the detriment of corporate goals and values. In order to raise performance and quality, employee behavior has to change. Leaders are often aware of this, attempting to change employee attitudes—and therefore behavior—through broad communication programs. But this approach tends to trigger self-defense mechanisms. People prefer to stay within their established way of working—if they see no rational reason to change. Simply telling them to change is not enough.

To change the behavior of employees, you have to adjust the context in which they work. This might mean making change within processes, organizational structures, performance metrics, incentive systems, or the distribution of roles and tasks. In the medium term, values and attitudes will shift, which then leads to a sustainable improvement in quality.

It’s crucial to understand how employees are behaving—and why—in order to change their context.

In one example, a company became aware that employees were only following rules and processes when it was absolutely essential. Project managers monitored quality criteria for full compliance but did not question the results. Their performance was evaluated more on the basis of adherence to budgets and time schedules than on long-term quality goals, such as nonquality costs in production or warranty costs.

At another organization, employees placed more weight on costs than quality—behavior that was a direct result of the fact that their superiors looked primarily at cost metrics and did not emphasize quality metrics.

And at another, cross-divisional cooperation took place in development only sporadically, even though it was prescribed in the standardized development processes. Employees explained that involving colleagues from other departments would slow down coordination and decision-making processes when they had ambitious time-to-market targets to reach.

Such behavior often results in unnecessary costs, delays in launching new products because of elaborate error correction late in the process, dissatisfied customers, and dissatisfied employees.

Changing the context can correct the root causes of behavior issues. Employees have to see fast decision making and a focus on sustainable improvements as useful, worthwhile, and rational. And management has to move employees from having a silo mentality toward embracing a cooperative culture.

Six Ways to Foster Cooperation

Observing six simple rules can help foster cooperation and reduce complexity, often leading to a noticeable change in behavior within a short period of time.

- Understand what employees do. A crucial first step is to gain a true understanding of the work that employees and colleagues do and why they do it. Cross-regional and cross-functional roundtables can be a helpful method for developing a common understanding.

- Reinforce integrators. Cooperation will thrive when the right people from different functions are at the table, all with clearly defined and understood roles and responsibilities. For example, include R&D as well as quality-department people within the development process. Flatter hierarchies will increase the power of individuals and therefore minimize escalations and increase the speed of quality-related decisions.

- Increase total quantity of power. By creating new power bases, such as operator self-control in assembly lines—and not just shifting existing power—ownership of quality is spread more broadly.

- Increasing reciprocity. Set rich objectives and eliminate internal monopolies in order to foster cooperation. Shared incentives among different functions can go a long way.

- Extend the shadow of the future. Leaders can encourage a long-term perspective in employees and ensure sustainable solutions by, for example, penalizing R&D engineers for warranty costs and encouraging cradle-to-grave product responsibilities.

- Penalize those who don’t cooperate; reward those who do. Measures such as implementing a penalty for hiding failures—since failures can be great sources of improvement—can help eliminate silo-like thinking.

In order to foster cross-functional cooperation, an automotive OEM applied numbers 1 and 2 from this list. The company implemented a quality council to foster a cross-functional common understanding about quality issues and required actions. The roles of the quality council, quality management department, and functions are now clearly defined. This has led to flat hierarchies and fast decisions.

Another automotive OEM leveraged number 5, extending the shadow of the future. R&D engineers had previously only been incentivized to adhere to budget and timeline. Now the project manager for the development of a new car has the burden of the warranty cost of the former model, which comes in addition to cost-saving targets for the new model.

At a toy manufacturer, rewarding those who cooperate—number 6—is an important part of the company’s values. The CEO has stated that he expects cooperation from his employees—a value that has become engrained in the culture. No one is blamed for failures, only for not helping others.

Quality Transformation Program

Changing corporate culture requires a holistic transformation program with an end-to-end view. A few adjustments made here and there will not suffice. Such a program typically addresses a number of issues:

- Governance. It is often necessary to streamline organizational structures and adjust roles and responsibilities in order to speed up decision-making processes and embed sustainable quality metrics within evaluation systems.

- Quality Processes. Some less-than-ideal behavior is caused by process and system inefficiencies. It’s important to make sure that necessary information is shared among divisions and processes are clearly defined and standardized—avoiding a silo mentality.

- Capabilities. A range of methods that can promote cross-divisional cooperation are available for preventive quality management, but these are often not used because of insufficient training. Further, people tend to have negative views of the quality function, thinking of it as an area reserved for employees coming to the end of their careers. To remedy these issues, groupwide training programs should include quality-measurement methods as a standard feature. And quality has to be promoted as an interesting career option, a move that will raise its perceived importance and lead to better awareness.

- Communication. Strategic communication is an important accompanying measure. Management needs to find ways to embed the importance of quality in the minds of employees through appropriate communication, such as email newsletters or staff meetings. It is also a good idea to regularly communicate positive quality-related news, such as the results of customer satisfaction surveys, customer quotes, any decline in nonquality costs, or employee prizes awarded for outstanding quality.

Success with quality transformation requires three far-reaching adjustments within companies.

Corporate management has to show commitment to the cause. Transparency—in this case, a clear understanding of the work everyone does—begins at management level and trickles down to lower levels. Top-level management should lead and participate in cross-functional quality meetings and hold regular discussions of quality status and improvement projects.

Top managers also need to participate in status meetings, such as reviews of quality programs and “quality gate” meetings. Many of the six abovementioned rules require fundamental changes in reward and incentive systems, processes, and organizational structures—adjustments for which corporate management support is absolutely vital.

There has to be cross-functional responsibility for quality transformation. Meaningful change to quality management needs to be implemented throughout the entire company, with measures rolled out across functions in order to boost cooperation among the departments from the very beginning.

The quality-management department might, for example, be made responsible for central coordination and communication. It could also promote governance issues in close cooperation with individual departments, as well as knowledge management and training. Cross-departmental teams must be made responsible for improving processes.

A central, systematic project management office is indispensable. This office is responsible for planning the program timeline and resources and implementing the project in waves in order to avoid disrupting the company.

It also has to ensure that implementation takes place within the set timeline and budget. A successful project management office—supported by experts from production, R&D, procurement, and supply chain management—holds regular review meetings with those responsible for each of the measures.

Leaders everywhere know that a culture geared toward quality is essential to long-term success and competitive advantage. To get there, they have to change employee behavior by transforming the context in which people work so that behavior leading to high quality becomes rational. The most important desired behavior should be cooperation across an organization, which means designing an overall setup that fosters that cooperation. A successful quality management program needs a holistic end-to-end view and must be at the top of every management’s agenda. Without it, companies are doomed to make—and repeat—costly mistakes.