T he Roman philosopher Seneca famously noted that institutions flourish slowly but fail rapidly. The same maxim applies to businesses. Take for instance Kodak, which was more than a century old when it was near its all-time sales peak in 2005; just six years later, it filed for bankruptcy.

How can companies today, faced with the growing threat of competitive disruption, avoid such catastrophic failure? Forward-looking leaders must avoid being deceived by traditional performance metrics and create new growth options before the path to collapse is unavoidable. Research in other fields, including biology and computer science, offers valuable lessons on when and how a business should innovate in order to maximize its chance of survival.

Why Do Systems Fail Fast?

Businesses, like biological ecosystems, are complex adaptive systems . Many thriving systems are based on positive feedback loops that propel growth. In nature, these may take the form of mutualistic relationships, in which species benefit from each other—for example, bees collect nectar and pollen from plants for sustenance, pollinating the plants, creating more food sources to allow further growth in the bee population, and so forth. Similarly, in business, a desirable new product creates consumer demand, which drives sales, permitting further product entries and investment to grow the market, and so on.

However, systems also face countervailing forces—negative feedback loops—that limit growth. In biological systems, growth may be constrained by the depletion of food or other necessary resources. In business, success may encourage imitators that saturate the market and commodify the product, or disruptors with superior offerings that can rapidly undermine the incumbent’s business. Further, high production levels may cause negative environmental effects or other externalities, eventually precipitating a backlash from regulators or consumers.

Traditional business metrics and strategies tend to reinforce these negative feedback effects. Firms mostly measure themselves by backward-looking metrics like sales and profits, which are lagging indicators of sustainability. And once a successful business model has been developed, companies often become “financialized,” seeking primarily to maximize efficiency and value extraction from core offerings. From this perspective, marginal investments in innovation may seem too risky. Cutting investment, however, reduces the diversity of the company’s growth options, thus creating systemic risk that may be triggered by shifts in demand or competition.

The modeling of complex systems, such as businesses, indicates that for a wide range of plausible parameters, the decline can be much faster than the rise . Furthermore, the dynamics that lead to destruction begin even before sales or profits have peaked. Business leaders must therefore act preemptively—they must invest in innovation even while the existing model is still lucrative.

The dynamics that lead to destruction can begin even before sales or profits have peaked.

Companies Are Failing Faster

As most leaders know, the ramp-up speed of new businesses is accelerating in the digital age. Whereas it took Walmart 18 years to reach $1 billion in revenue (the fastest ramp-up in history at the time), it took Facebook only six years and Pokémon Go only seven months. This is a consequence of the low asset intensity and inherent agility of increasingly prevalent digital business models.

What is less often discussed, however, is that firms are also falling more rapidly. Our analysis shows that only 44% of today’s industry leaders have held their position for at least five years, down from 77% a half-century ago.

Thus, preemptive innovation is now more important than ever for incumbent companies. How can leaders effectively pursue such a strategy?

Lessons from Biological Systems

Biological organisms have been competing in complex systems for billions of years and have evolved strategies that enhance long-term success in a continual game against nature, and against others. Their actions reveal useful hints for business leaders on when and how to pursue new options:

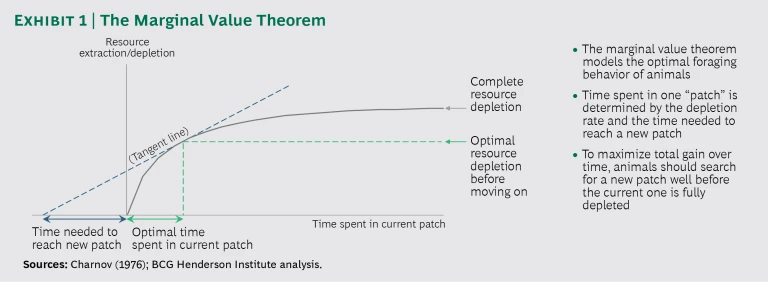

- Anticipate exhaustion. Many animal species forage in “patchy” environments, where they must continually decide whether to keep feeding from the current patch—gradually exhausting its resources— or search for a new one . The marginal value theorem (MVT) explains why it is optimal for animals to begin searching well before they exhaust their current patch, and several empirical studies show that species such as birds and monkeys actually follow this rule. (See Exhibit 1.) This would be a good strategy even in the absence of competition, but competition increases the need to find new patches before others do.

Unlike foraging animals, business leaders don’t face a binary choice between exploitation and searching—they can devote resources to both in parallel. But the MVT shows that companies should make sufficient investments in innovation well before their current growth engine is exhausted.

- Mix big and small steps. Biological species provide hints not only on when to explore but also how to explore efficiently. For example, bees search for flowers in a manner comprising many small steps and occasional very large steps, known as a Lévy flight , to reduce their dependence on any single region. (See Exhibit 2.) This “long-tailed” step distribution can yield optimal search results—especially when the value of patches is uncertain, because animals can use the information gathered from each patch to better understand the environment.

In business, innovation efforts should not be limited to either “big steps” or “small steps.” Instead, firms should leverage both in tandem—big steps to move to uncharted terrain and small steps to uncover adjacent options at low cost—and learn from previous attempts to identify new opportunities.

- Embrace evolution. Over long timescales, biological organisms adapt to changing environments through natural selection. This process requires creating variation in genetic code, such as through sexual reproduction, which recombines viable genes in a modular way. Even bacteria use a form of modular recombination through the horizontal transfer of genetic information that exists outside of chromosomes, on strings of DNA known as plasmids. Furthermore, some species, including most strains of E. coli, experience more frequent mutations under stress to increase their adaptability. (This is in marked contrast to most companies, which tend to decrease their rate of exploration and “stick to their knitting” when subject to financial or competitive pressures.)

Business leaders should create variation though experimentation and let the market choose winners, especially when the environment is uncertain. For example, Alibaba rotates a portion of its senior leadership through its various business lines each year, not merely to improve the skills of individual leaders but to combine institutional knowledge from different sources—a form of “genetic recombination” that increases variation and accelerates the firm’s evolution .

Lessons from Computer Science

The study of algorithms also provides hints on strategies for preemptive innovation. Several types of problems can be solved with heuristics that, while sometimes counterintuitive, demonstrate when and how to pursue innovation.

- Constantly explore. A deep-pocketed gambler walks up to a row of slot machines and contemplates which ones to play—an example of the multi-armed bandit problem. Since the payout distributions are unique and unknown, this optimization problem is quite complex. (During WWII, it frustrated scientists so much that some supposedly suggested it be dropped on the enemy, “as the ultimate instrument of intellectual sabotage.”)

2 2 Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths, Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions, Henry Holt and Co., 2016. The gambler’s natural response might be to focus exclusively on the machine that has had the highest payout so far. However, a superior solution (as measured by the Gittins index) also considers that playing other machines provides new information about their payouts, which may be valuable in the future. In practice, this strategy balances “exploitation” of the best-known machines with “exploration” of all other options—crucially, never devoting all resources to exploitation alone.

Much like with slot machines, the true value of potential innovations is uncertain, so it may be tempting to focus on those that promise the biggest short-term payoff. However, to maximize long-run performance, leaders should always preserve some resources to explore alternative offerings, regardless of where their business is in its life cycle.

- Search broadly first. A truck driver needs to deliver packages to 100 different locations using the most efficient route. This so-called traveling salesman problem is another puzzle that has vexed mathematicians for decades. It is an example of many common problems in which it is not feasible to analyze every option before having to choose one. Several of the best-performing algorithms for such problems—including tabu search and simulated annealing—search broadly for alternatives at first, rather than settling on local solutions that may not be the best ones. These methods narrow down a specific solution only after assessing a broad range of options.

Similarly, business leaders should start with a wide scope when exploring new innovations and make “big moves” across the space of potential options, refining narrowly with “small moves” only once the best direction is clear.

- Embrace randomness. An algorithm is learning how to play Atari games—an example of how AI can be trained to accomplish goals in a complex environment. One class of algorithm that can often solve such problems effectively is known as “evolutionary strategies.” These methods start with initial decision parameters and then inject random variation into the decisions, testing all the resulting options, selecting the best one, and repeating the process. This can result in strategies that are too far-fetched to design using human intuition but actually yield better results.

When making decisions at all levels of the business, leaders should not be afraid to inject some random variation and test the results empirically, rather than relying too much on analysis and intuition to design solutions.

When making decisions at all levels of the business, leaders should not be afraid to inject some random variation and test the results empirically.

Lessons from Business

Preemptive innovation is a challenge for incumbent firms: short-term investor pressures can discourage investment, and past success tends to entrench the current business model. But some firms have managed not to box themselves into a corner:

approximately 10% of large incumbents

are still growing at double-digit rates.

- Run a portfolio of growth options. Forward-looking firms manage a balanced portfolio of bets that span various timescales. For example, pharmaceutical companies know that each drug has a finite life cycle, determined by competition and patent duration. Given the very high costs of drug development, they have developed systematic mechanisms for managing the balance between exploration and exploitation. Innovative firms run multiple bets using a stage-gate development process, which minimizes the costs of failure while allowing successes to be amplified and exploited.

- Acquire the right capabilities. To create successful innovations continually, incumbents need the right strategic capabilities. While some firms may be able to build those internally, another viable path is to acquire disruptive companies. This requires a different mindset than traditional M&A deals made to increase scale or efficiency. Instead, the goal is to achieve “ post-merger rejuvenation ,” in which the incumbent injects itself with new capabilities and entrepreneurialism to avoid stagnation. For example, Disney’s acquisition of Pixar did not merely result in cost synergies or the cross-promotion of movies—it was also a vehicle for self-disruption. Rather than forcing its own practices on Pixar, Disney adopted parts of the acquiree’s leadership team and culture, new capabilities that enabled it to compete in new ways.

- Maintain dynamism and diversity. Firms that leverage a diversity of ideas are more likely to challenge the existing model and find new sources of growth. Compositional diversity is one factor—our research on more than 1,700 companies in eight regions shows that having a diversity of backgrounds in management is positively correlated with innovation . But successful firms must also have an environment that promotes variety in thought, communication, and the diffusion and competition of ideas. For example, Morningstar Foods has adopted an extreme “no-hierarchy” structure that allows for “a lot of spontaneous innovation and ideas for change [to] come from unusual places.”

- Use a balanced set of metrics. The familiar benchmarks of sales, profits, and growth will not disappear. Nor should they—measuring current performance is still important for business leaders and investors. But these metrics should be complemented with forward-looking measures that aim to assess the firm’s vitality, its capacity for growth and reinvention . Leaders who look only in the rearview mirror might be content with the metrics they see. But, like Kodak and other incumbents, they will miss the warning signs of the cliff that lies ahead.

Past performance is a poorer and poorer indicator of future success. In today’s highly complex business environment, failure can come faster than ever—so incumbent firms cannot be complacent. To avoid falling off Seneca’s cliff, it is crucial that business leaders look forward as well as backward, and invest in new sources of growth before the peak of their current models is imminent.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit

Featured Insights

.