This article is part of the ongoing BCG series Strategic Procurement in the Digital Age, a comprehensive discussion of practices companies should follow for top procurement performance.

As business cycles quicken, procurement functions are under pressure to purchase goods and services faster than ever. Digital technologies can greatly accelerate the overall procurement process—the chain of actions that begins with recognizing the need to buy an item or service and ends with payment and delivery. We estimate that new digital solutions can reduce the end-to-end time for this process by as much as 80% for simple items like office supplies and 40% for complex items like capital projects. These improvements can in turn boost savings on spend by 1% to 3% and relieve procurement professionals of much labor.

But given the vast numbers of processes to consider and technologies available to address them, many companies struggle to create speedy and user-friendly solutions that stick. We’ve found that a combination of traditional and digital methods yields the best results.

Conventional Approaches: The Link Between Processes, Speed, and Savings

Procurement processes fall into three main categories:

- Planning-to-strategy (P2S) processes begin with the allocation of procurement department resources for each product category and end with the defining of category strategies.

- Source-to-contract (S2C) processes start with the defining of individual projects and their needs and end with the signing of supplier contracts.

- Procure-to-pay (P2P) processes begin with the decision to buy a good or service and end with delivery and payment.

Planning-to-strategy activities often take place in an agile, project-based environment, so there are generally no real speed issues. But S2C and P2P processes can be inordinately slow. Orders for office supplies, for example, can take weeks instead of hours, while contracts for more strategically important items can take months instead of weeks.

The ramifications go far beyond the procurement function. Companies that can’t react fast enough to market changes lose a crucial source of competitive advantage. This holds just as true for the fashion retailer that needs to keep up with current trends as it does for the airline that wants to have token items on hand to give away after the national team unexpectedly wins the world soccer championship.

Typically, procurement processes are sluggish because they are inadequate, their systems are fragmented, or their users are unaware of how things should function. Optimized processes promote speed because they establish efficient ways to react to change and remove ambiguity about how things should be done. They also generate savings and reduce risk because they make it likely that more people will follow the correct procurement procedures.

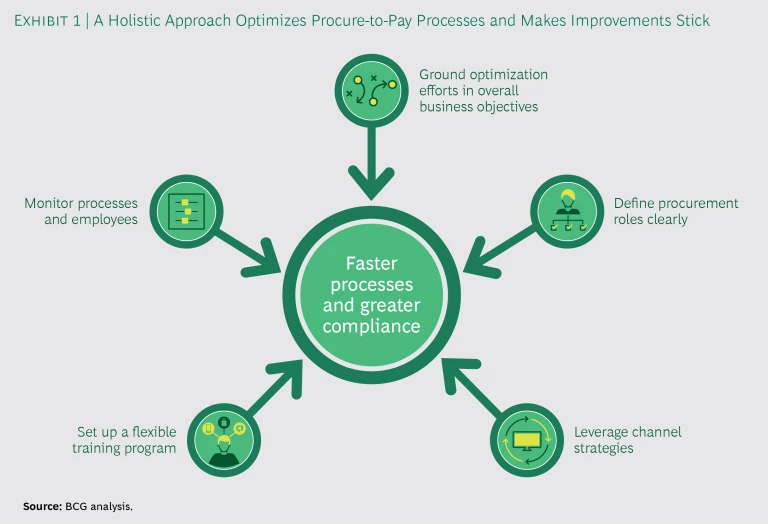

To derive the greatest possible value from conventional methods, companies need to adopt a comprehensive approach that includes five key actions. (See Exhibit 1.)

Ground optimization efforts in overall business objectives. Strategic goals should guide all process optimization efforts. Companies must first determine where speed is most needed, and then balance that requirement with other considerations. If the goal is to meet day-to-day demand more quickly, is it more important to be fast in new supplier onboarding or in day-to-day P2P operations? At the product or service category level, it may be critical to purchase some large machines faster than usual, but is it worth forgoing the required technical approvals?

Define procurement roles clearly. It’s important to clarify who is working on each process and to ensure that they are the procurement staff with the most relevant experience and knowledge. This will help eliminate situations such as the contract delays that occur when strategic buyers are forced to spend their time on tasks that should have been allocated to operational buyers.

Clearly defined roles will also solve the problems that arise when too many employees are allowed to make purchase requisitions. Limiting the number of such employees would allow those who remain involved to gain more experience and, consequently, perform their work with greater competence and speed. Moreover, fewer people would need training in purchasing policies and systems, likely resulting in greater process compliance and lower use of resources.

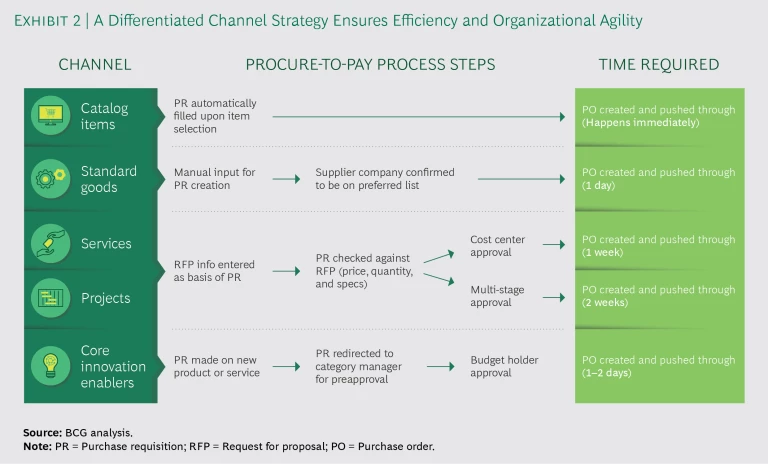

Leverage purchasing channel strategies. Speed is more important in some categories than in others, so channels should be deployed accordingly. For example, in categories considered critical for innovation, companies can reduce the number of suppliers to accelerate the speed of the S2C processes, while keeping a larger number of suppliers for categories where savings are more important.

This holds true for P2P processes as well. While the requisition process for simple products like office supplies should be relatively straightforward, complex requisitions, such as those for major capital projects, require a lengthier process with multiple technical approvals. Developing a different channel for each type of requisition will help ensure that each process moves at the fastest pace possible. (See Exhibit 2.) If a particular project is critical to innovation and therefore requires a speedier requisition process, the procurement department should allow some of the more time-consuming steps to be bypassed, as a tradeoff between speed and either savings or risk. In addition, business units across different geographic regions should use the same channels.

Set up a flexible training program. As procurement systems have become more sophisticated, the purchasing experience has come to resemble the online shopping experience, which is fairly intuitive. But there may still be occasions when employees need to purchase items or services that are not featured in the catalog. Without proper training in the more complex procedures required in such situations, they are likely to make orders via phone or email, slowing down the process as a result.

A training program that covers both online and in-person procedures is a good way to quickly familiarize people with the purchasing process, while promoting a high rate of adoption and building awareness of the importance of adhering to established P2P processes. Moreover, it provides maximal flexibility at minimal cost.

Monitor processes and employees. Monitoring the pace of activity along the entire chain of S2C and P2P processes is essential for the categories that are strategically most important. Dashboards can be used to communicate the findings to procurement management and key external stakeholders. Typical S2C metrics include the time needed for supplier onboarding. A common P2P metric measures the time from when a purchasing requisition is made to when a purchase order is sent to a supplier.

It’s also critical to monitor employee compliance. Although circumventing systems and processes may seem like a faster way to get something done, it can greatly compromise speed and savings targets. Establishing KPIs makes it possible to keep track of individual employees on a regular basis.

Harnessing New Digital Methods

Although conventional approaches can accelerate procurement processes, there’s still much room for improvement. That’s where newer digital technologies come in.

Digital transformations are just beginning to gain steam. According to our research, only 25% of companies have significantly increased process efficiency through digitization, and only 20% have implemented digital processes from purchase order through payment. An even smaller portion (17%) have succeeded in completing digital implementation projects as planned—on time, on budget, and with the expected impact.

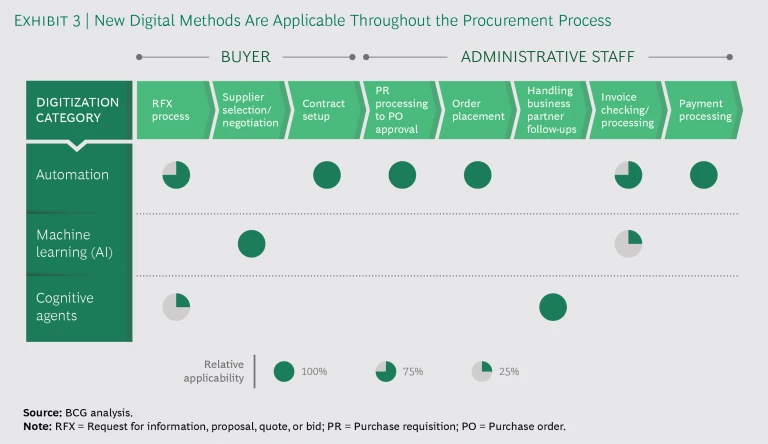

The Key Technologies. In the past few years, a variety of technologies have matured to the point where they can make a significant difference in operational procurement processes. (See Exhibit 3.)Technologies from each of the three main categories—automation, AI, and cognitive learning—are critical in optimizing day-to-day procurement processes.

- Automation. Undoubtedly, automation is the predominant technology for optimizing operational procurement processes because most of the activities are repetitive in nature. Automation can replicate repetitive manual tasks at several times the speed and accuracy rate of people. It could potentially reduce the number of full-time operational staff needed for transactional tasks by up to 50% over the next two years—and by an even larger percentage in the long term.

Robots, for example, can compare data, fill out forms, and, in the form of chatbots, interact with users. They can check the purchase requisitions coming in from plants, translate the requisitions into purchase orders (POs), and even send the orders directly to business partners. After the orders are placed, bots can check to see whether suppliers have responded, and send reminders if necessary. In combination with optical character recognition and other technologies, some robots can handle standard processes like invoice checking, while others can take on payment processing. In the past, a person drove the process and deployed a machine when suitable; now a machine drives the process and people are deployed to handle exceptions.

A construction material manufacturer suspected that its suppliers were overcharging for materials and services. The company programmed a robot to automatically pull and compare all invoices, POs, and goods-received data from the ERP system. Upon detecting a significant deviation, the bot took a screenshot and sent it to the responsible buyer, who then assessed the charge and followed up directly with the supplier. As a result of this automation-assisted effort, the manufacturer reclaimed from suppliers a total of €3.6 million, 2% of its spend.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI). Machine learning is another high-potential technology for optimizing procurement processes. In contrast with robots, it can recognize patterns in data and make decisions regarding various possible solutions. Decision algorithms enable machines to learn and make choices based on their “intuition,” that is, on the basis of past experience, or on a set of rules provided at the outset. AI used in conjunction with bots can optimize a great many P2P processes.

Machine learning is useful for handling a purchase requisition, for instance. While a bot can translate the requisition into a supplier-ready purchase order, it can’t detect errors—for example, it can’t tell whether the order has been sitting in the wrong purchase channel because a user filled out the wrong form. Machine learning can be trained to look for breaks in patterns that reveal an error, such as the wrong supplier’s name, the wrong product or service category code, an amount of spend that is too small, or an address that is an office location rather than a plant site. It then calls for a double-check of the order by asking the user, “Are you sure you want to place this order?”

AI technologies can also decide if it makes more sense to send a PO to a preferred supplier than to send a request for quotation (RfQ) to a few suppliers. Here the technology looks at not only the volume of the purchase but also the characteristics of the category and the current state of the market.

AI is useful for dealing with the results of a RfQ as well. Algorithms can evaluate suppliers on different parameters (such as price, quality, and innovation potential) and identify the combination of supplier offers that creates the most value. This highly analytical, multi-round process can last several weeks. AI can even evaluate tender results to find optimal supplier combinations in a fraction of the time it takes humans.

These technologies can also play a role in identifying abnormal behaviors. Some solutions are now able to screen transactions for outliers, such as several purchase orders placed to the same supplier for an amount below what’s usually allowed.

In addition, AI can automatically identify acceleration opportunities. For example, a European packaging producer wanted to optimize the speed of its processes. Although robots and non-complex detection AI were able to significantly increase the speed of certain standard processes, supplier evaluations of greater complexity still took a long time. The company deployed an AI-based tendering evaluation tool to assess the results of a facility management RfQ that covered 162 sites, 6 subcategories, and a total of 85 suppliers.

The tool quickly analyzed the hundreds of possible supplier scenarios. At one extreme was the cherry-picking option that entailed 36 suppliers, each providing at least one service at the lowest price. This option would have resulted in the greatest savings but was neither desirable nor feasible because it involved so many suppliers. At the opposite extreme was the bundling option, where just three suppliers would together provide all of the items needed, but with significantly less savings for the packaging producer. The optimal solution was somewhere in the middle. The buyer and the manager saw that the tool accomplished in seconds what would have taken them four days—and after the four days they would not have been certain that they had found the best solution.

- Cognitive Agents. Operational processes also benefit from cognitive agents. Using natural language processing technologies and acting as chatbots or voice over phone, these agents can be deployed to answer supplier and business partner requests, functioning in much the same way as Apple’s Siri or Amazon’s Alexa. Accessing information from customers’ ERP systems, the agents can serve as a hotline for internal employees and suppliers who have questions regarding the timing of deliveries.

- Other Technological Solutions. Some digital technologies, such as apps that are used on the shop floor to scan goods received, directly address the need for speed by eliminating what were once very long paper-based processes. Other software is useful for identifying processes that are either broken or not being followed. Blockchain deserves mention as well. Although the technology’s impact on speed is still limited, its potential is enormous because it will make it much easier to verify information about products and suppliers. Blockchain will prove especially important in high-cost or high-quality categories like jewelry or airplane parts, where supplier compliance with standards is crucial and automatic verification increases speed.

Four Must-Follow Rules for Developing Best-in-Class Digital Processes

Digitizing procurement processes is not an easy task. There are a great many technologies to consider and users to consult. The following principles can help:

- Get the mandate from the top. Many companies do not consider procurement processes to be of central importance, so they do not put much emphasis on optimization efforts. Given the increasing importance of speed as a competitive differentiator, top management needs to make it a priority and make sure it’s reflected in company targets.

- Focus on creating user-centric processes. With the digital tools available today, procurement departments have the opportunity to design processes that resemble the Amazon shopping experience. But optimal results require that a wide range of functions, including finance, engineering, and supply chain, take part in the design process. They need to take an end-to-end view to understand any problems that arise, such as inconsistencies between agreed-upon prices and invoice prices, delays in approvals, and requisition errors that require manual correction. Frequent touchpoints with real users are essential for getting end-to-end visibility, as is process mining, which detects delays due to procedures not being followed.

- Build a new procurement operating model. Because process digitization puts machines in charge of many tasks that were once carried out by people, the procurement function must make some substantive changes to its operating model. It will be critical to define roles for displaced employees in which they can add greater value. One option is to put them on the front line with internal business partners and suppliers. This is a good way to keep a human face on things as machines increasingly take on the task of responding to requests. We also recommend setting up a procurement digital command center (in departments that have sufficient staff to run one). The center will ensure that the technologies are running smoothly.

- Adopt agile ways of working. One of the chief goals of process digitization is to develop—and sustain—an agile approach. This includes cross-functional teaming, taking measured risks, monitoring progress to confirm or kill initiatives, and viewing failure as acceptable (as long as it doesn’t drag on). It also means launching newly digitized processes early and often, with the goal of developing minimum viable products that take the needs of the user into account.

In the future, the speed and efficiency of procurement processes will become even more vital to competitive advantage. Companies that accelerate their processes now will be ahead of the game later on. But process digitization is a major undertaking, requiring vast amounts of time and resources. CPOs need to lead the charge in determining which processes to focus on and which technologies to deploy. Their vision is crucial to realizing digital’s full potential.