In the course of its more than 145-year history, Danske Bank has weathered recessions, panics, and booms. But the 2008 financial crisis was a particular challenge. Like all European banks, Danske Bank found itself struggling with a stagnant economy, a weak lending environment, and a tougher regulatory climate. Leaders were also concerned about the solvency of Greece and other troubled EU economies. And as consumers were becoming increasingly digital, their expectations were changing markedly.

Compounding these external challenges were a number of internal issues. In its main markets, Danske Bank lagged behind competitors in customer satisfaction levels. Its operating costs were relatively high, too, and its balance sheet before the crisis struck had been weak relative to its peers’. In 2009 alone, Danske Bank had loan impairment charges totaling nearly DDK (Danish kroner) 26 billion, an amount equal to 43% of the bank’s total income. On top of this, the bank’s concentration of business in Denmark left it more exposed to local amplification of external shocks than its more geographically diversified competitors were.

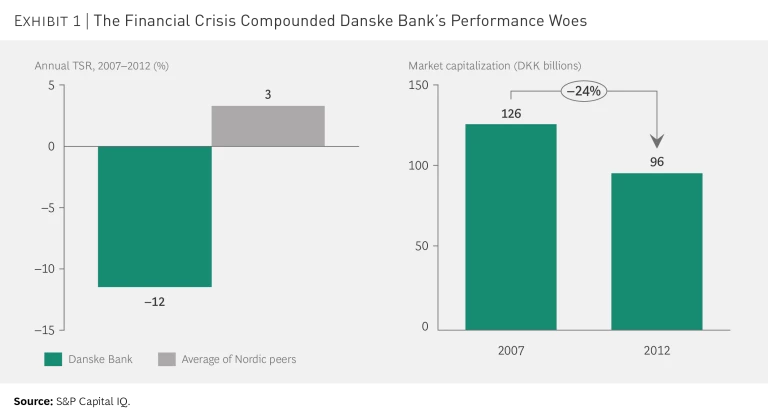

The financial crisis and these exacerbating factors took a dramatic toll on Danske Bank’s overall performance. From 2007 to 2012, the bank’s market capitalization fell by almost 25%, from DKK 126 billion to DKK 96 billion. (See Exhibit 1.) And while its Nordic banking peers produced an average annual TSR of 3%, Danske Bank’s TSR was –12%.

In the wake of the financial crisis, the bank’s leaders acted quickly to stabilize performance. To strengthen its balance sheet, Danske Bank issued new shares—resulting in an infusion of capital that boosted its credit rating—and withheld dividends for five years. Although loan impairment charges continued, they declined from their once-critical level. Danske Bank also carried out a modest workforce reduction and raised its lending rates to offset the higher cost of funding resulting from the EU’s increased capital requirements.

By 2012, its leaders had restored the bank to a sound financial footing. They were now ready to begin the next phase of their longer-term plan to make Danske Bank a top performer and to chart a path for future growth.

Crucial to this phase of the turnaround was the implementation of significant measures to improve profitability. The bank increased its noninterest income throughout its business lines by adjusting pricing, reducing fee discounts, and promoting cross-selling. It also streamlined its operations—including revamping its channel approach to make the branch network far more efficient—and replaced its country-centric structure with integrated business units. At the end of 2012, Danske Bank had 400 branches throughout Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and Norway; but by the end of 2016, only 217 remained. In 2013, the bank announced its intention to withdraw from the personal banking business in Ireland. Two years later, it announced plans to do the same in Latvia and Lithuania. These actions enabled Danske Bank to reduce its total full-time-equivalent staff by 1,000 from the end of the year in 2012 to the end of the year in 2016.

These measures quickly improved the bank’s financial picture, but they also triggered an unexpected decline in customer satisfaction and company image across a broad set of stakeholders. Recognizing that a renewed focus on customers needed to be the cornerstone of future value creation, the bank’s leaders launched significant efforts to improve the customer experience, deepen relationships with corporate and institutional investors, and reemphasize the customer perspective in its everyday decision making. As part of these efforts, the bank aimed to become a leader in digital services and the digital customer experience; for example, it introduced MobilePay, a smartphone app for making money transfers, payments, and donations. MobilePay has been a big success, especially in Denmark, where more than 60% (3.6 million) of the country’s population are now regular users.

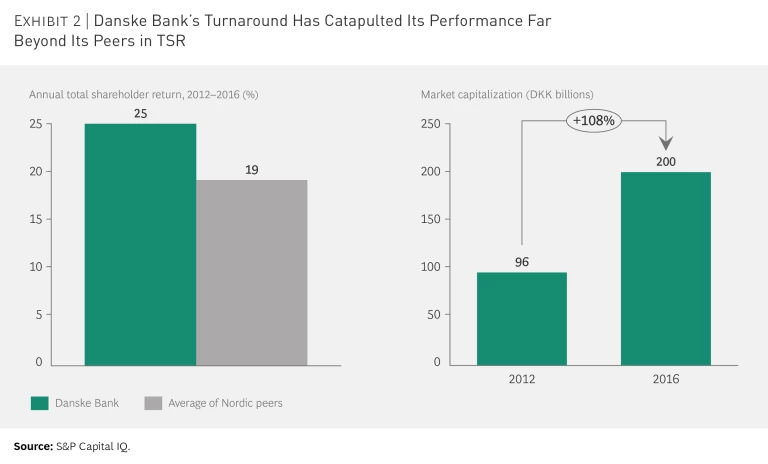

In eight years, by adhering faithfully to its performance improvement plan and its rediscovered customer-centric mindset, Danske Bank engineered an impressive comeback. It dramatically boosted its operational efficiency. It reduced operating expenses relative to total income by 20 percentage points, from 67% in 2008 to 47% in 2016—an accomplishment that, along with top-line growth and diminished loan impairment charges, returned Danske Bank to its precrisis profit level. From 2012 through 2016, Danske Bank soared past its Nordic peers in TSR: 25% versus an average of 19%. (See Exhibit 2.) And its market capitalization more than doubled during the period, from DKK 96 billion to DKK 200 billion.

Beyond its impressive financial results, Danske Bank has seen major improvements in customer satisfaction. By the end of 2016, it had reached two important goals: becoming one of the top two Nordic banks in customer satisfaction in business banking (in all four key markets) and becoming one of the top two in personal banking (in three out of four key markets).

Danske Bank now has a solid foundation on which to leverage its adaptive strategies for growth: focusing on the customer experience, driving digitalization, building up high-potential segments, and expanding business across its Nordic markets. With its newfound strength and resilience, Danske Bank is poised for enduring prosperity as it heads into the second half of its second century.