African business is integrating Africa—economically and otherwise. It has been a long time coming, and plenty of hurdles remain, but the economic integration of the continent, which many see as key to its continued development, is manifest. Driving it are indigenous entrepreneurs and fast-growing African companies, as well as multinational corporations (MNCs).

Since 2010, BCG has been tracking business and economic development in Africa, with a focus on the roles of leading African companies and MNCs. Our first report examined global competitors newly emerging from Africa. (See The African Challengers: Global Competitors Emerging from the Overlooked Continent , BCG Focus, May 2010.) Our second report looked at the changing development model of Africa and how companies needed new approaches in fast-changing business environments. (See Winning in Africa: From Trading Posts to Ecosystems , BCG Focus, January 2014.) And our most recent previous report analyzed how nimble, agile, and fast-growing African companies were often beating MNCs at their own game. (See Dueling with Lions: Playing the New Game of Business Success in Africa , BCG Focus, November 2015.)

This report continues to track the progress of African companies, focusing on how they are driving the continent’s economic integration by expanding their operations and their capabilities. Their activities are starting to overcome the barriers that have long restricted African nations from greater business and economic interaction. African companies look to Africa first for growth, and removing barriers is crucial to their strategies. Their primary goal, of course, is to build value for their owners, but they understand that their activities also further economic and social development, and that this dynamic creates environments in which their businesses can thrive. Integration is therefore both a strategy and a highly desirable outcome.

Fragmentation: A Barrier to Business

Businesses often mention fragmentation, in its many forms, as a problem in Africa:

- “It costs less to ship a car from Paris to Lagos than from Accra to Lagos.”

- “Getting visas in Africa, especially for my African staff, is a nightmare.”

- “Africa is an interesting market—but so fragmented. Many countries are just too small. How can I generate critical mass? Where should I start?”

- “There is no ‘One Africa,’ but a collection of many different markets.”

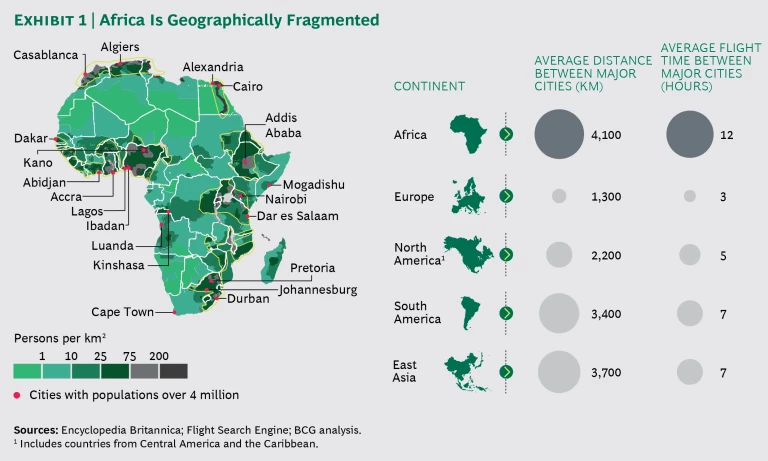

Start with simple geography—that’s far from simple. (See Exhibit 1.) Africa is vast, but only a handful of its cities have populations of 4 million or more, and they are dispersed across the continent. Direct flights are few, and flight times are long—the longest in the world, on average, at 12 hours between cities, including connections. From any city in Europe, you can reach the countries aggregating 70% of Europe’s GDP in 3 hours or less. In Southeast Asia or Latin America, a comparable trip takes 8 hours. It Africa, a similar journey requires 15 hours—one full waking day.

Then there’s the issue of geopolitical and economic fragmentation. Africa has 54 sovereign countries—more than four times the number in South America and triple the number in East Asia. Most African countries are small in population and economic activity, if not in landmass. It takes 24 African nations to aggregate $1 trillion in GDP—far more than any other region of the world.

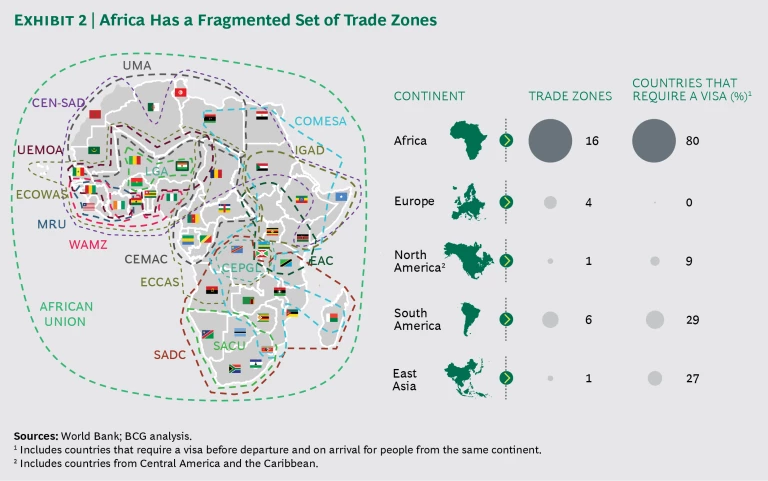

More important, most of Europe has combined into a single trade zone, the EU. In contrast, Africa has 16 trade zones, many more than South America (which has 6) and East Asia (which has 1). Four-fifths of African nations require a visa to visit. (See Exhibit 2.) The Abuja Treaty, signed in 1991, contemplates an African Economic Community, but progress toward continent-wide free trade has been slow and uncertain and involves multiple steps, including the creation of multiple regional economic communities in 1991, a continent-wide customs union in 2019, a common market in 2023, and projected economic and monetary union in 2028.

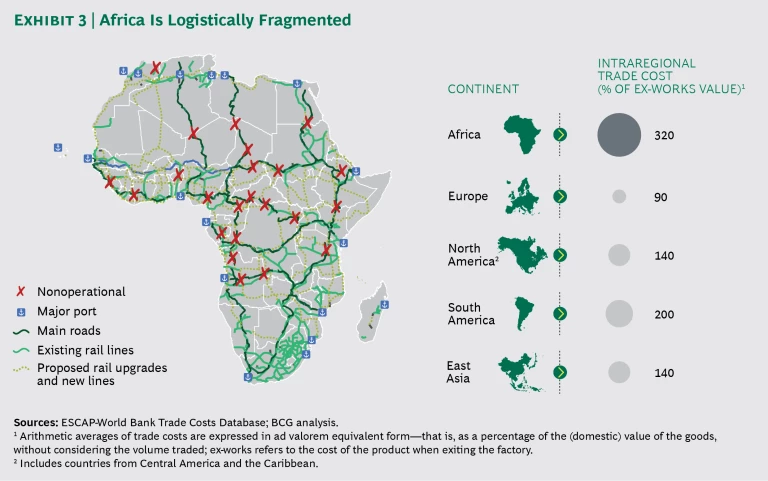

Logistical fragmentation is yet another concern. (See Exhibit 3.) Despite many new infrastructure initiatives, Africa lacks major road and rail networks to connect people and businesses across the continent—and many of the roads and rail lines that do exist are in poor repair and end at nations’ frontiers. This greatly increases the cost of doing business. We calculate that the average cost of shipping and distributing goods to market in Africa is equal to 320% of their value, compared with 200% in South America and 140% in East Asia and North America.

Fragmentation in Africa is much greater than anywhere else in the world, and it adds significantly to the economic challenges facing countries that typically lack the critical mass to compete globally.

Continued Growth and Integration…

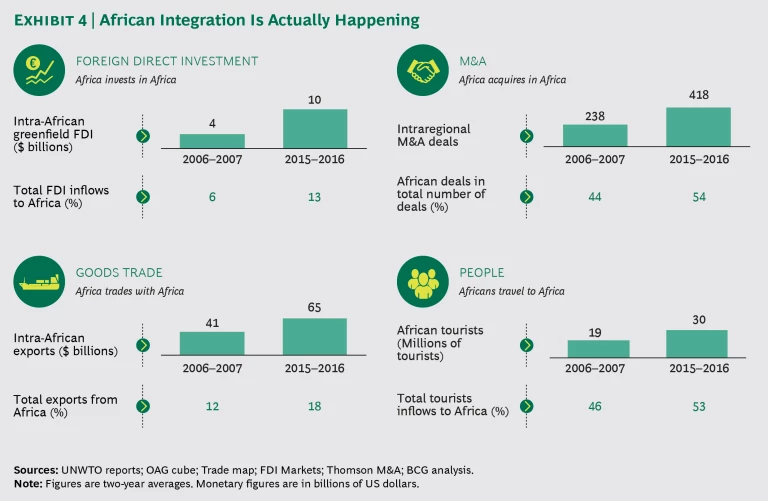

Despite the barriers of fragmentation, economic integration in Africa is not only taking place, but also gathering speed. We see more signs of this progress with each passing month, quarter, and year. The primary drivers come from within the continent, led by African business. Africa invests more in Africa, Africa trades more with Africa, and Africans travel more to Africa.

Four statistics—covering foreign direct investment, goods trade, M&A, and people—provide insight into the key advances. (See Exhibit 4.) Between 2006–2007 and 2015–2016, the average annual amount of African foreign direct investment—money that African companies invested in African countries—nearly tripled, from $3.7 billion to $10 billion. Over the same period, the average number of yearly intraregional M&A deals jumped from 238 to 418, with African-led transactions representing more than half of all African deals in 2015. Meanwhile, average annual intra-African exports increased from $41 billion to $65 billion. And the average annual number of African tourists (Africans traveling in Africa) rose from 19 million to 30 million. African tourists made up more than half of all tourists on the continent in 2015–2016.

…Led by African Corporate Entrepreneurs

As we observed in Dueling with Lions, the extent to which scale, access to technology, and access to capital are exclusive advantages of MNCs has greatly diminished. African companies have grown fast, thanks to four competitive advantages that they have carefully cultivated:

- Focus—a full commitment to Africa

- Field—on-the-ground experience and proximity to decision makers

- Facts—a superior grasp of data and information relevant to local markets

- Flexibility—the ability to make quick decisions and navigate informal business environments

In the past decade, African companies have used these advantages to expand not only within their home markets but to other parts of the continent as well, a trend that has accelerated in the past few years. In the process, they are spearheading economic integration. On average, the top 30 African companies now have operations in 16 African countries, up from an average of only 8 in 2008. In effect, these companies are expanding into one additional African country every year.

Consider just three industries.

African airlines have rapidly expanded the number of countries that they serve, often establishing routes and stations ahead of actual passenger demand. Ethiopian Airways flew to 36 nations in 2016, up from 24 in 2006. Royal Air Maroc serves 30 countries (twice as many as in 2006). Air Côte d’Ivoire flies to 17 countries, and RwandAir to 16. African airlines are making intra-African air connectivity—a prerequisite to economic integration—a reality.

African financial institutions are championing trade and expansion, the glue of economic integration. For example, three major Moroccan banks had expanded their operations from 3 countries in 2005 to 14 countries by 2016 and had financed a fivefold increase in Moroccan exports to those nations.

Telecom operators and media companies are doing their part to advance pan-African connectivity and communications. The West Africa Cable System, an alliance of 12 operators, has connected 11 African countries and Europe. A separate alliance of 20 operators has connected 17 West African nations and Europe. As a result, internet penetration in Africa passed 30% in 2016. African and international media companies are facilitating the free flow of information, ideas, and personal connections through their media operations as well as through increasingly high-profile meetings and events. CNBC Africa, BBC Africa, Africa 24, and Africanews are developing into pan-African outlets. Events such as the Africa CEO Forum, organized by the Jeune Africa Media Group and the Mo Ibrahim Forum, attract business leaders and decision makers from across the continent.

In addition, international logistics companies such as Maersk, Bolloré, Barloworld, and Imperial Logistics International, are facilitating greater trade. From 2005 to 2016, they helped drive an increase in intra-African trade of almost 120%, from $30 billion to $64 billion, while almost doubling the average number of African countries that they serve.

Introducing 150 Pan-African Pioneers

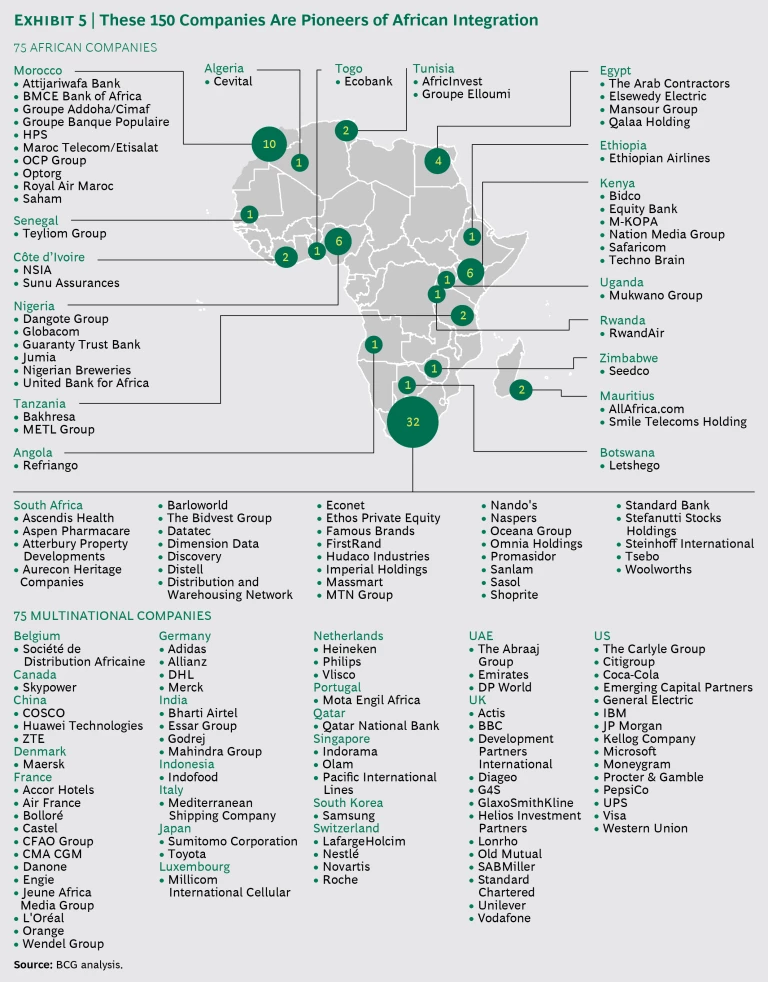

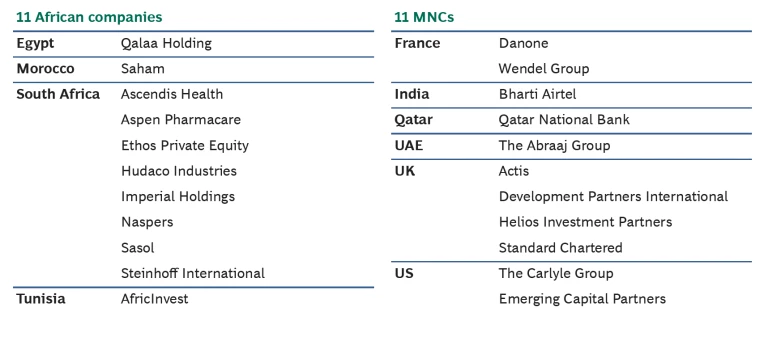

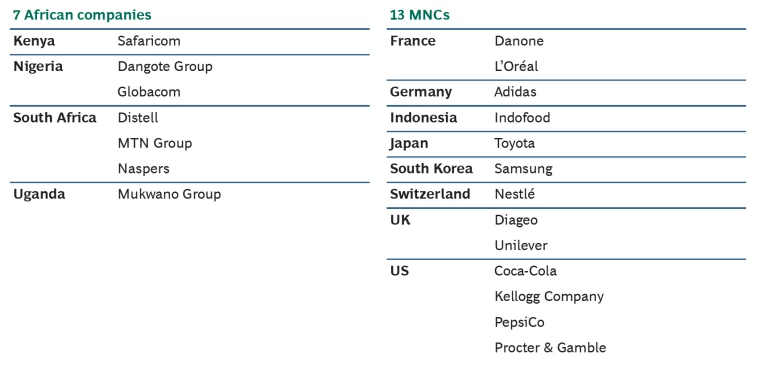

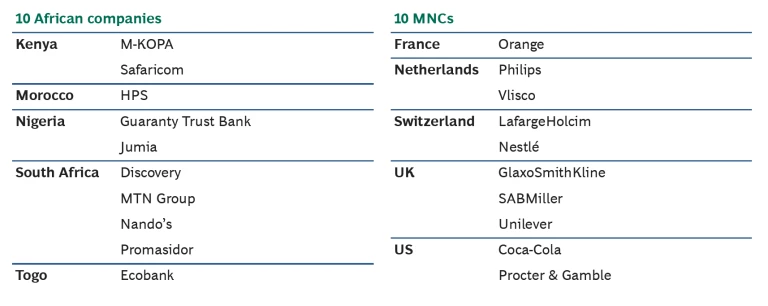

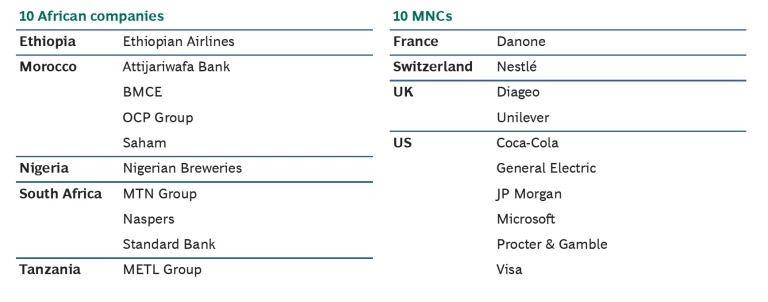

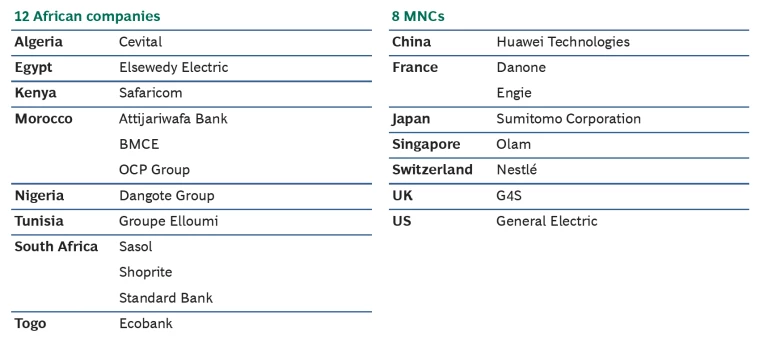

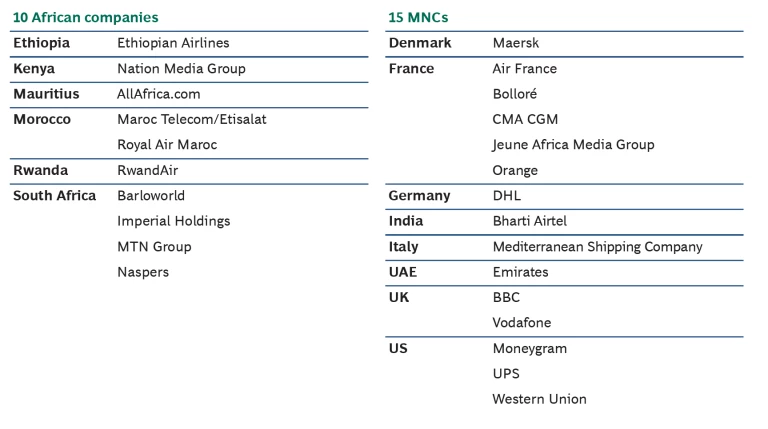

We have identified 150 companies that are blazing a trail toward a more integrated Africa. (See Exhibit 5.) They consist of 75 Africa-based companies and an equal number of MNCs that have established impressive track records in Africa and are contributing to further integration. The African pioneers come from 18 countries on the continent: 32 are based in South Africa and 10 in Morocco; Kenya and Nigeria are home to 6 each; 4 are from Egypt; and 2 each come from Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritius, Tanzania, and Tunisia. The MNCs are a global group, with France, the UK, and the US most strongly represented. At the same time, a dozen MNCs from China, India, Indonesia, Qatar, and the UAE are active across Africa.

In our 2013 Winning in Africa report, we highlighted characteristics that winning companies had in common. Many of these factors define how the pioneer companies expand, grow, and create value—not only for their owners and employees, but also for the countries in which they do business. African pioneers do eight things:

- They actively expand their footprint.

- They make greenfield investments.

- They use M&A to expand.

- They build brand recognition.

- They innovate locally.

- They develop a people advantage.

- They build local ecosystems.

- They connect Africa by facilitating the movement of people, goods, data, and information.

We next explore how these companies are making their impact.

Footprint

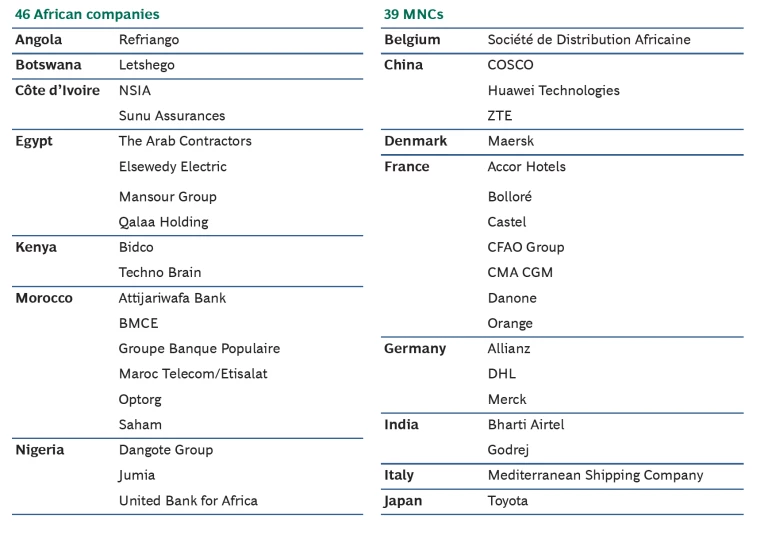

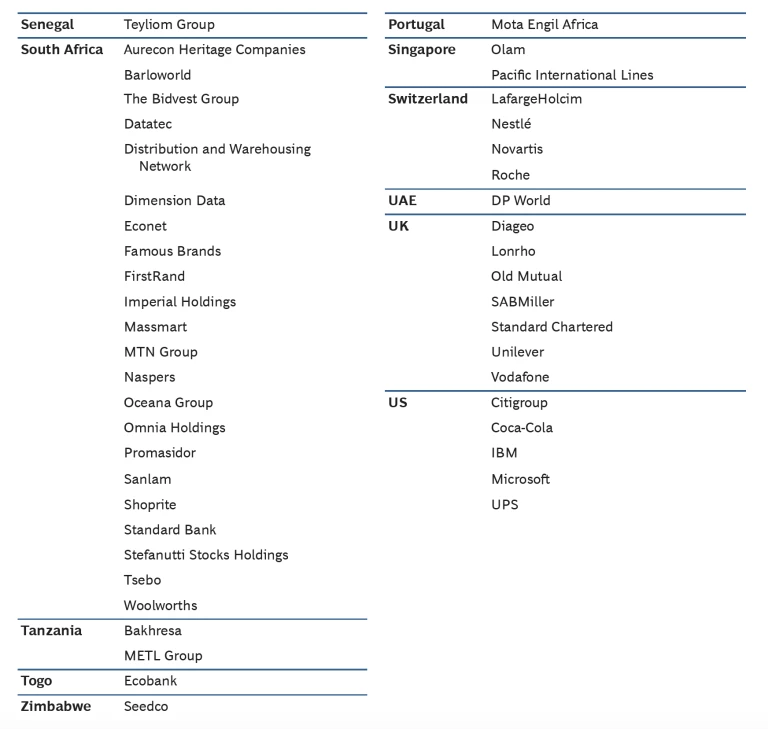

We have identified 85 companies that have a large African footprint (which we define generally as having operations in at least ten countries), and 46 of these companies are African. They are active in the financial, consumer and retail, industrial goods, technology, and logistics sectors, among others.

Of the 46 companies that are headquartered in Africa, 22 are based in South Africa and 6 in Morocco, but the rest are geographically diverse. Their leaders tell us that, besides encouraging them to seek growth in new markets, a multicountry footprint enables them to mitigate the risk of volatility and instability in some African countries and to better understand the diverse cultural dynamics and customer needs underlying disparate consumption patterns, trade channels, and business environments across the continent. (See “ Drawing a Route to Market for Multinationals in Africa ,” BCG article, June 2017.)

Take Attijariwafa Bank and BMCE Bank of Africa, both of which have their headquarters in Morocco. With more than 700 and 560 international branches in 14 and 20 African countries (aside from their home market), respectively, Attijariwafa and BMCE have become the two largest banking groups in Africa in terms of footprint. Their international operations are growing fast, too. In 2016, BMCE’s sub-Saharan African operations contributed more than 40% of the bank’s revenues and more than 30% of its net income.

Or consider France’s CFAO Group. Founded in 1852, the company has been active in Africa for more than 150 years. It operates in 35 countries on the continent and serves as the distribution backbone for numerous other MNCs, including Carrefour and L’Oréal. Toyota Tsusho Corporation acquired CFAO in 2013 and consolidated all of its Africa assets in 2017, enlarging its footprint even more.

Huawei Technologies, a Chinese multinational company and a leading global provider of information and communications technology solutions, has used an asset-light strategy to extend its reach in Africa over the past 20 years. Huawei entered Kenya in 1998 and now operates in more than 30 African countries. It has built more than 70% of the numerous commercial 4G networks that operate in Africa. Huawei recently expanded its offerings to include smartphones, and it sees the continent as a key destination for its products. In 2016, the company introduced its 6-inch smartphone in Egypt and South Africa as part of the first wave of a global launch.

Greenfield Investments

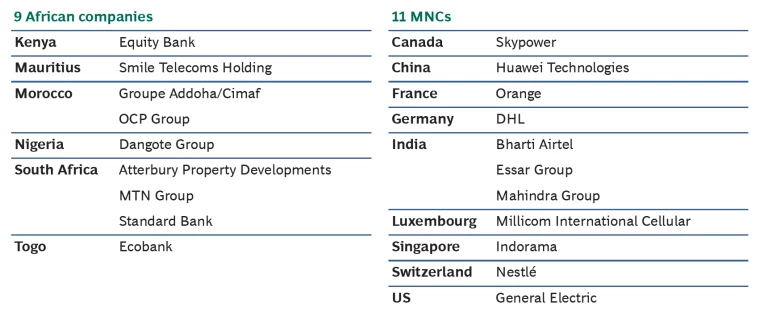

In an encouraging development for multiple emerging African economies, 9 African pioneers and 11 MNCs are making significant greenfield investments in manufacturing facilities and other business infrastructure. Just as encouraging, these companies are reaping attractive returns.

For example, Dangote Group of Nigeria, one of the largest conglomerates in Africa, established cement factories in six African countries in 2014 and 2015, including a $480 million plant in Ethiopia. Dangote’s African operations outside its home market now contribute almost 30% of the group’s revenues.

Groupe Addoha of Morocco has adopted a two-pronged strategy for expanding in sub-Saharan Africa: it invests in both building-materials factories and real estate in several countries. Addoha has acquired land in five countries (Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Cameroon, Congo, and Sierra Leone) in order to develop up to 50,000 housing units, including low- and middle-income housing. It has also invested in cement factories in ten African countries, including Ghana and Burkina Faso, to supply construction materials for its real estate projects.

Samsung is notable among multinational companies for having ramped up its African presence aggressively in recent years with investments in new manufacturing facilities. These include a $280 million computer and air conditioner assembly plant in Egypt in 2013 and a $20 million television assembly plant in South Africa in 2014. The company also has invested in customer service and training academies in Kenya, Nigeria, and Ethiopia. Samsung is the top-selling consumer electronics company in Africa and plans to double its share of revenues from Africa to 20% of the company’s total sales by 2023.

M&A

Both African companies and MNCs are making acquisitions in Africa, giving them quick access to new assets, markets, and customers. Acquisitions also help companies obtain new talent and skills, as well as staff with knowledge of a particular industry or sector in a new market.

Danone, a French MNC, has used M&A to accelerate its growth in East Africa, with a two-step acquisition of Brookside, the region’s largest dairy player. Danone bought 40% of its target in 2014 and purchased the rest in 2017. It has also invested in Fan Milk in West Africa.

The India-based telecommunications services MNC Bharti Airtel gained immediate access to 42 million subscribers in 17 African countries when it acquired Zain’s Africa business for $10.7 billion in 2010. The company increased its number of subscribers in those countries to 63 million in 2013 and to 76 million in 2015 before selling two subsidiaries and reducing its footprint to 15 countries in 2016.

Brand Recognition

Africans value brands. Our 2016 report on consumer sentiment in Africa, based on survey results from 11 countries, confirmed that Africans are discerning consumers who make well-informed purchasing decisions and are willing to pay more for higher-quality goods—especially nongrocery items. (See African Consumer Sentiment 2016: The Promise of New Markets , BCG Focus, June 2016.) While affordability is important, price is typically not the most significant factor when African consumers decide what to buy. For example, durability and functionality are more important to buyers of home electronics, and taste is the most important factor to beer purchasers. In addition, the social approval of a brand plays an increasingly important role in purchasing decisions.

Although leading brands vary widely across product categories, African consumers tend to prefer global brands to brands from regional companies. For example, Samsung is Africa’s favorite mobile electronic brand, followed by Nokia and Apple. That said, for all companies that do business in multiple African countries, building successful brands with an African identity encourages the idea of Africa integration and helps drive exports of Africa’s products.

As one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies, UK-based Unilever takes care to pursue Africa-relevant strategies for all of its brands in Africa. The company’s overall strategy is to increase its social impact by ensuring that its products meet consumers’ needs. Unilever balances such qualities as nutrition and hygiene with affordability, and it ensures that its products reach all levels of the consumer pyramid by using tools such as door-to-door sales. It adopts marketing campaigns to suit African markets, with a focus on local celebrity endorsements.

In similar fashion, a locally focused marketing strategy backed by continuous investment turned Indofood’s Indomie brand into Africa’s most popular noodle brand. Marketed by Dufil Prima Group, a joint venture between Indofood and Tolaram Group, Indomie is the market leader in Nigeria, for example, with a market share of 70%. Sales growth has been significant: Indomie tripled its annual revenues in Nigeria to more than $600 million between 2009 and 2014. The company has invested in manufacturing facilities in Morocco, Nigeria, Egypt, Sudan, Kenya, and Ethiopia, from which it distributes to virtually the entire continent.

Some local brands are well on their way to becoming African (and international) icons. Distell’s Amarula has a strong South African heritage and is respected for its authenticity and social development program. It has established itself as the number two cream liqueur brand globally by volume sold and is a top-ten most requested brand in the liqueur category.

Local Innovation

Necessity, they say, is the mother of invention, and companies in Africa—both local firms and MNCs—must innovate if they are to address the widely varying needs of African customers and the structural difficulties of doing business (such lack of infrastructure and a predominance of highly active informal economies). Thanks to this innovation, Africans’ lives are getting better.

In a recent BCG survey of more than 150 top African executives, participants nominated a number of companies in multiple industries for exemplary innovation.

Although Vlisco is based in the Netherlands, its fabrics are designed to meet the tastes of African consumers for high-end clothing. The company has developed four brands to appeal to demand for different styles. The company registers 95% of its sales in Africa, illustrating how critically important to success integration in Africa and innovation that caters to local tastes can be. For a local market, South Africa’s Promasidor developed a product that overcomes logistics and infrastructure challenges to ensure that children have access to nutrition. Cowbell is a milk powder packaged in small sachets; the company replaced animal fat with vegetable fat to make it more affordable and to give the powder a longer shelf life, thereby diminishing the need for a cold supply chain.

People Advantage

According to our survey, which included entrepreneurs and executives representing more than 60 companies in ten countries, the biggest single challenge facing African businesses is “growing and retaining local talent.” Developing and retaining staff in a very competitive environment is difficult, but there is a double payoff: the company builds its capabilities and at the same time advances social development in the countries where it operates.

For example, Tanzania’s METL Group, which employs 24,000 people, plans to build its staff across Africa over the next four years to a total of more than 100,000. It relies on local talent and provides similar hiring, training, and development support in all the countries in which it operates.

Morocco OCP Group, a leading fertilizer producer and one of the top greenfield investors in Africa, is committed to training new talent by partnering with some of the world’s most prestigious universities, including Columbia, MIT, and HEC Paris. The company is supporting the development of a global higher education institution that it established in 2014, the Mohammed VI Polytechnic University, which focuses on research and learning in mining and agriculture. Once seen as a stodgy state-owned company, OCP has become Morocco’s preferred employer of young talent.

Leading employers, such as Danone and Unilever retain top talent by offering employees competitive pay packages and benefits, technical training, incentives such as performance bonuses, and opportunities to learn and grow. They also offer the kinds of perquisites that people associate more closely with tech centers such as Silicon Valley: recreational activities and onsite facilities such as gyms, beauty salons, and ice-cream parlors.

The good news is that Africa has a rich and growing labor pool, and Africa’s workforce is better educated than ever before. Although adult literacy rates across Africa are still below global averages, they rose from 57% in 2000 to more than 66% in 2016. Continent-wide, the student-to-teacher ratio in primary education shrank from 42 students per teacher in 2001 to 35 students per teacher in 2016. In secondary schools the ratio fell from 26 students per teacher in 2001 to 21 students per teacher in 2016.

Local Ecosystems

Africa’s multitude of marketplaces can pose myriad challenges related to the informal economy, multiple local stakeholders, and restrictive regulations, among other things. These factors are more than most companies can manage on their own. Both African pioneers and experienced MNCs have learned that in many cases it takes an ecosystem to build a business and that investing in a good ecosystem can be a source of competitive advantage. By extending a pan-African company’s impact through local organizations and institutions, a local ecosystem also promotes growth and social development.

For example, China’s Huawei Technologies is working to overcome the digital divide that persists in many African economies. The company has launched training for 10,000 ICT professionals in Nigeria; it has helped more than 3,000 schoolchildren in South Sudan gain internet access for the first time; it has donated tablets and computers to schools in several countries; and it is working with Vodafone to build an “instant network school” at a refugee camp in Kenya.

Elsewedy Electric has production facilities and turnkey projects in power generation, transmission, and distribution in Africa.

The OCP Group’s approach covers the entire value chain, including local construction of fertilizer plants, development of logistics and distribution capabilities, and investment in research that is specific to the regions in which it operates (mapping soil fertility and corresponding fertilizer needs, for example). In Nigeria, OCP is partnering with Dangote Group to boost fertilizer production. OCP also signed an agreement with the association of fertilizer producers and suppliers in Nigeria to further develop the fertilizer market in that country. Similarly, in November 2016, OCP signed a deal with Ethopia's Chemical Industries Corporation to build a $3.7 billion fertilizer production plant in eastern Ethiopia.

Connecting the Continent

A number of companies operating in the telecommunications, media, finance, and transportation sectors (among others) are contributing to the integration of Africa in varied ways. They facilitate communication, interaction, and the movement of people, goods, information, and money among African countries and between these countries and the rest of the world. One of the largest companies on the continent, with a market cap approaching $70 billion, is South Africa’s Naspers, which provides television, print media, internet services, technology products, and book publishing in multiple countries. Its digital satellite TV platform serves 8 million subscribers in sub-Saharan Africa, and it launched a budget option, GoTV, to bring digital TV within the means of millions more.

Ethiopian Airlines flies to more destinations in Africa than any other carrier, and it currently serves about 100 international destinations from its hubs in Africa. The airline is also the continent’s largest cargo operator, as measured by volume. The inauguration in 2017 at Addis Ababa Airport of Ethiopian Airlines’ $150 million, state-of-the-art cargo terminal, with the capacity to handle 1 million tons of cargo per year, enhances the carrier’s ability handle fresh produce and pharmaceutical products.

Linking 20 destinations in Africa, Emirates transported more than 5 million air passengers to and from the continent on more than 21,000 flights in 2015. Emirates Skycargo has been facilitating trade in the region for more than a decade.

Operating in 45 countries across Africa, Maersk, an integrated transport and logistics MNC headquartered in Denmark, has been in Africa for more than a century. It is seeing an uptick in trade within Africa as many long-standing internal trade barriers have begun to fall.

The Challenges Ahead

African Lions and MNCs alike face plenty of challenges, starting with fragmentation in all of its manifestations and extending through the difficulties of attracting and retaining talent and managing a plethora of local stakeholders. But if the past decade has demonstrated anything, it’s that these companies can overcome adversity masterfully. They’ve built impressive track records of creating value for themselves and advancing the development of the continent—and its many economies—against the odds. They have a strong tailwind of momentum. They understand the challenges ahead, and they know that continuing to drive the integration of the African markets where they do business is one key way to pave the road to greater success. By trailblazing the much-needed economic integration of Africa, these companies are making a difference for African business and economic development.