Editor’s note: Two authors, Michelle Akers and Anson Dorrance, participated in the events described in this article. For the sake of simplicity, their experiences and recollections are presented in the third person.

“We play for each other.”

This guiding philosophy of the 1990s US women’s national soccer team—as articulated by Anson Dorrance, its coach during the first half of the decade—propelled the squad to unparalleled success. The team won the inaugural Women’s World Cup in 1991 and the first gold medal awarded to a women’s soccer squad at the 1996 Olympics. It concluded the decade by defeating China in the thrilling 1999 World Cup final.

The team did not just win the big games but dominated throughout the decade, compiling a remarkable record of 155 wins, 21 losses, and 9 ties while outscoring opponents by an average of three goals per game. “We wanted to dominate, to crush every single team every single minute of every single game, as individuals and as a team,” said Michelle Akers, one of the star players.

The team was notable not just for its victories. The players redefined the role of women in sports, fighting for gender equality, equal pay, and the reputation of women’s soccer. They willingly subjected themselves to brutal training and conditioning sessions in order to attain those goals.

“They can be credited with nothing less than the founding of women’s soccer as an international game,” wrote Sally Jenkins in The Washington Post. “The worst that could be said of them was that they were joyous carousers. They were one of the few things left in sports you could watch without suspicion.”

How many businesses and organizations today have been equally dominant? How many can say that their employees truly “play for each other” and for a higher purpose? In our experience, not many. To be sure, the US squad had stars, such as Akers and Mia Hamm, but the stars themselves attributed their success to team alchemy.

Playing for each other is what happens at effective organizations. In these institutions, people cooperate—they seek group success over individual attainment and accomplish more than the sum of their individual achievements. Unfortunately, this happens infrequently because few organizations are designed to promote cooperation.

A BCG approach called smart simplicity unlocks organizational effectiveness by systematically encouraging cooperation. While hard to achieve, cooperation is easy to see in the success of such dominating sports teams as the Golden State Warriors, the New England Patriots, Bayern Munich, and the All Blacks, New Zealand’s national men’s rugby team.

We chose sports teams as the canvas to show how other organizations can promote cooperation and improve performance because of sports’ consistent rules and binary outcomes. We chose the US women’s soccer team of the 1990s, specifically, because it was arguably more successful for a longer period than any team in any other sport.

The Mess Facing Organizations Today

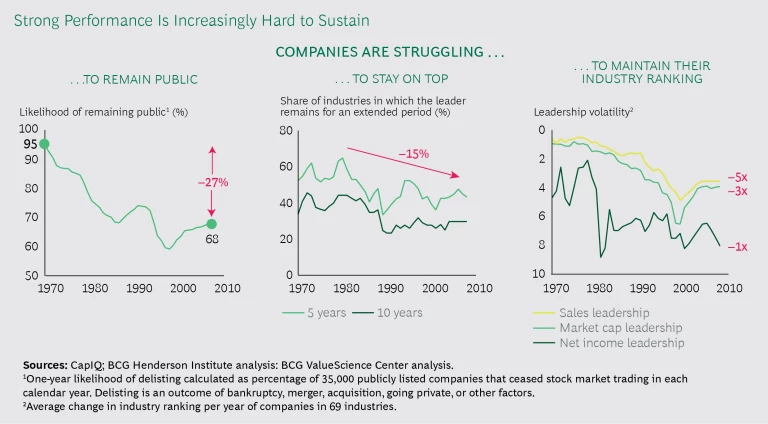

Most businesses and organizations do not perform close to their peak potential, and even when they do, they struggle to sustain that level of performance, especially in today’s climate. We know this empirically through shorter corporate lifespans and rising volatility rates. (See the exhibit.)

And we know it in our gut. High-performing organizations are buzzing with activity, excitement, and possibility. Teams work together—they cooperate—to achieve common objectives. But at many organizations, the lethargy is palpable. People are motivated, just not on the job. They apply their talents in their hobbies and volunteer work, or with their friends and family.

Why do great things happen so seldom or so fleetingly at so many large organizations? One major reason is that most organizations still rely on outmoded management theories born of the assembly line. These theories were developed in a simpler time when most work was rote and precision was more important to organizational success than critical thinking. They assume that people are the weak link and need to be controlled through rules (the “hard” approach) or through team-building activities such as offsite retreats, affiliation events, and even lunchtime yoga classes designed to foster camaraderie (the “soft” approach).

These approaches to management may have been effective when most work was algorithmic—routine—based on following a set of rules. But thanks to increasing competition, globalization, digitization, and regulation, today’s economy is far more complex. Business problems have become more dynamic, and ambiguity and uncertainty have grown. Work has become heuristic, an exercise in problem solving requiring intelligent judgments and the resolution of often contradictory requirements.

Heuristic work is responsible for 70% of new-job growth in the US today. For this type of work, people cannot simply fall back on rules, because the nature of the work requires the interpretation of rules—and there are no rules to interpret the rules. In fact, rules have become counterproductive, creating bureaucracy, hindering cooperation, and frustrating employees.

A Smarter and Simpler Approach

Smart simplicity is an antidote to organizational complexity, bureaucracy, and lethargy. It unlocks latent energy and enthusiasm by encouraging cooperation.

Thomas Edison once said that genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration. That famous quote misses the critical role that cooperation played at his labs, which were populated by teams of “muckers”—tinkerers, machinists, and scientists who collectively tested, tweaked, and built his inventions. When cooperation, inspiration, and perspiration come together—as they did in Edison’s labs and with the US women’s soccer team in the 1990s—great things happen.

The role of leaders today is to provide inspiration while encouraging perspiration and, ultimately, cooperation. Inspiration gives people a reason to perspire—to work their butts off. But inspiration and perspiration are not enough to break through the entrenched bureaucracies of most large organizations. People, teams, and entire organizational units also need to work together, since few of today’s complex problems can be solved by individuals acting independently. Hence the need for cooperation.

People are not irrationally uncooperative. They behave the way they do in order to meet individual objectives and are influenced by the resources and limitations of their workplace—or what we call context. There are always good reasons for their behavior—even when, if viewed from the perspective of the organization and its goals, that behavior appears irrational or dysfunctional.

Smart simplicity encourages cooperation, not by attempting to control people or force them to behave differently, but by understanding their objectives and changing the work context in such a way that cooperation becomes a rational goal. By shaping context, leaders can inspire, foster hard work, encourage cooperation—and achieve incredible results. (See “Six Simple Rules.”)

Six Simple Rules

Six Simple Rules

These rules help unlock performance by encouraging cooperation. The first three empower people. The rest harness that autonomy in the service of cooperation.

- Understand what your people really do. Analyze the work context to understand what people actually do and why they do it. With this understanding, you can use the other rules to foster cooperation.

- Reinforce integrators. Identify roles whose success depends on fostering cooperation across the organization, and then support those roles with the resources they need to be successful.

- Increase the total quantity of power. Figure out ways to give people more power without taking power away from others.

- Increase reciprocity. Make each person’s success dependent on the success of others.

- Extend the shadow of the future. Create direct feedback loops that expose people to the consequences of their actions.

- Reward those who cooperate. Provide greater opportunities, recognition, or financial rewards to those who cooperate, and punish those who fail to do so.

That may seem abstract, but it was exactly what happened during the magical run of the US women’s soccer team in the 1990s.

Lessons from the Team

The US women’s victory over Norway to win the 1991 World Cup was a wakeup call for more storied soccer nations that had long dominated the men’s game. Traditional powerhouses such as Brazil and Germany dedicated themselves to building world-class women’s teams. But despite their efforts, the US women kept winning, culminating in the victory over China in the 1999 World Cup. Two head coaches and a rotating cast of supporting players were responsible for this dynasty.

Two of the contributors to this article were integral members of that team, and we rounded out their perspectives and experiences with multiple in-depth interviews with other team leaders, including captains Julie Foudy and Carla Overbeck; Lauren Gregg, an assistant coach during the 1990s; and Tiffany Roberts, a key reserve. We also interviewed members of winning men’s teams, such as Bayern Munich. (See “The People We Interviewed.”)

The People We Interviewed

The People We Interviewed

Julie Foudy was a member of the US women’s national soccer team from 1987 to 2004, its co-captain from 1991 to 2000, and its captain from 2000 to 2004. She chose a career in soccer rather than medicine after her graduation from Stanford University and now works as an ESPN broadcaster.

Lauren Gregg played on the 1986 national team and was assistant coach on the squad from 1989 to 2000, serving briefly as head coach in 1997 and 2000. She was also the head coach of the women’s soccer team at the University of Virginia for ten years.

Philipp Lahm was captain of Bayern Munich, the professional team he played for during most of his career. He also captained the German national team when it won the 2014 FIFA World Cup and is considered one of the greatest defensive players of all time.

Carla Overbeck was a three-time All-American selection at the University of North Carolina, a member of the national team from 1988 to 2000, and a co-captain (with Foudy) in the 1990s. She is currently an assistant women’s soccer coach at Duke University.

Tiffany Roberts was selected for the national team in 1994, when she was 16 years old, and played through 2003. She is currently the head coach of the University of Central Florida women’s soccer team.

The interviews revealed three distinct practices, all grounded in the six simple rules, that fostered cooperation among the team’s members. They worked well on the field, and they can likewise take hold in executive suites, on shop floors, and in field organizations.

Provide a Higher Calling

Organizations extol the virtues of a clear mission and vision. While clarity is important, the ambition itself must be resonant and uplifting. For most employees, revenue targets and profit margins are not reasons to get up in the morning. Leaders must give them an authentic higher calling, a mission that inspires—not corporate gobbledygook.

Anson Dorrance became the national team coach in 1986, one year after the team’s founding as a somewhat ragtag collection of largely unknown players. In the early years, they subsisted on $10-a-day meal money, traveled to distant games by bus, stayed in cheap hotels, and wore uniforms with ironed-on names and numbers.

Despite this humble origin story, Dorrance was able to instill a higher purpose by establishing goals that transcended wins and losses. As an American raised overseas, he wanted to show the world that the US could not be kicked around on the soccer field.

Akers remembers Dorrance telling the team, “Every time you step on the field you’re selling the game, changing minds, and changing the culture of what is possible for women and for everyone.”

Dorrance selected a group of teenagers that included Foudy, Hamm, Overbeck, Brandi Chastain, Joy Fawcett, and Kristine Lilly—“joyous carousers” who embraced this higher calling. “It wasn’t really for us. It was for the future of women’s soccer,” Overbeck recalled.

Leaders must give employees an authentic higher calling, a mission that inspires—not corporate gobbledygook.

The team fought with the US Soccer Federation to receive pay equal to that of the men’s team. Nine players, including Foudy, Overbeck, and Akers, were briefly locked out of training camp before the 1996 Olympics over the dispute. But the struggle helped galvanize the team. “We decided that, if we were going to get something done, we all had to be together,” Overbeck said.

On the field, Dorrance and his team did not just want to win; they wanted to crush their opponents, who viewed the US as a second-class soccer nation. “I was going to beat them with the tools of the American spirit,” Dorrance said. This translated into a simple but incredibly demanding strategy: the US would double every player on the opposing team, requiring players to train tirelessly in practice and on their own. As Akers put it, “We had a culture of ‘extra’—doing whatever it took to be the best. I trained harder knowing that my teammates were doing the same thing and that this was what it would take to accomplish our goals.”

Dorrance demanded that his players be in shape from day one. Early on, a player failed a training drill on the first day. Dorrance sent her home that evening. After that, no player arrived at practice out of shape for the remainder of his tenure.

These aspirations increased reciprocity (the fourth of the six simple rules), and therefore cooperation, in two important ways. First, they were audacious and beyond the reach of any single player. They made it rational for each player to subsume her individual goals to the team’s shared objectives. Second, they motivated each player to devote every ounce of her effort to the team’s interests. That’s what led Akers, for example, to endure over 30 orthopedic surgeries during her career. “Each of us had a role to play to help the team win. Part of mine was being the target for opposing teams.” Rather than shy away from this role, Akers embraced it. “By serving as the target, I could help others play more freely,” she said. “The more challenging it was, the more fun it was, and the better I got, so bring it on.”

These aspirations also extended the shadow of the future (the fifth rule). Players who failed to cooperate or who gave less than 100% damaged the team’s chances of winning and put at risk the larger goals of gender equality and women’s participation in sports.

Make It Clear That Every Player—Even the 20th—Matters

For reciprocity and cooperation to occur and for the higher calling to have meaning, players have to believe that their roles matter. This is not easy on a soccer team, where strict substitution rules limit the playing time of reserves. How do coaches keep players engaged when their role may not seem important?

This is not easy in business, either. It can be hard to motivate middle managers and frontline employees, who often don’t see how their efforts contribute to the larger purpose of the organization. But without the engagement of these players and employees, teams and organizations will fall short of their goals.

It’s not just a matter of paying lip service. Negativity can spread quickly on a sports team, especially among players who spend most of their time on the bench. The coaches of the US team were keenly aware of this challenge, which they aptly referred to as “engaging the 20th player.” The engagement—and ultimate success—of the entire team depended on the engagement of each member. One way the US coaches achieved buy-in from reserves was to elevate the importance of practice relative to games. As Gregg and Dorrance put it, games were simply an outcome of the training that occurred in practice.

Tiffany Roberts, all five-foot five-inches and 120 pounds of her, joined the team as an inexperienced 16-year-old but quickly made her mark through tenacious play in practice. Roberts’s gritty play “helped other players improve,” Gregg recalled. “She elevated the practice.”

Roberts’s selection didn’t just pay off in practice. In the semifinals of the 1996 Olympics against Norway, Tony DiCicco (Dorrance’s successor, who died in 2017) started Roberts and asked her to play a new position and to hound Hege Riise, the best player in Norway at the time, and arguably in the world. By neutralizing Riise, DiCicco hoped to win a 10-on-10 game. It worked. Roberts shut down Riise, and the US went on to win the semifinal match and eventually the Olympic gold medal. “It felt really good to know how much my team trusted me in such a big job,” Roberts said.

For reciprocity and cooperation to occur and for the higher calling to have meaning, players have to believe that their roles matter.

Even reserves who had lost their starting jobs bought in to the mission of the team. Dorrance remembers overhearing midfielder Tracey Bates talking to her mother on the phone about losing her starting job to Lilly, five years her junior. “‘Don’t you understand, Kristine is better than I am,’” Dorrance recalled Bates telling her mother.

Even when they did not play in a game, reserves received praise for their roles on the sideline. Akers described how coaches complimented bench players who ran water bottles to the starters during breaks. This mentality led to a running joke that the players were “socialists.” Joking aside, the focus on the 20th player increased reciprocity and cooperation. In other words, “whether I am the 20th player or a key player, whether I am a substitute or I start, whether I assist or I score, my role matters,” Gregg said.

Walk in One Another’s Shoes

Cooperation requires that leaders and coworkers understand what the other really does (rule number 1). Otherwise, it’s impossible for people to understand how to work together most effectively and for leaders to know which behaviors to encourage and reward.

The coaches of the US team encouraged this understanding in several ways. First, Dorrance meticulously tracked individual performance on the field. He refers to this tracking of individual performance as a “competitive cauldron,” which he then sought to balance with off-the-field camaraderie. “What’s critical for me as a coach is to recruit every single element to drive performance,” he said. He also wanted to understand the “internal narrative” of his players, the beliefs about themselves that both motivated and inhibited them. So he asked players to rank themselves on a 1 to 5 scale on such attributes as self-discipline, competitive fire, self-belief, love of playing the game, love of watching the game, and grit. “The first step in player development is for the player to figure out who she is,” Dorrance said. “A great way to unlock potential is to get the player as close to the truth of her internal narrative as possible.”

Second, in pregame meetings, coaches carefully tied the individual responsibilities of each player, including the reserves, to the broader objectives of the team. Players understood why their role—no matter how seemingly insignificant—mattered.

Finally, the coaches created “small societies,” player groupings—the “attacking front six” or the “defensive back four,” for instance—that had to work together effectively to help the team win. Dorrance borrowed this concept from the great Argentinian coach César Luis Menotti. The coaches set specific objectives that could only be achieved if each small society worked together as a unit.

In the men’s game, Pep Guardiola, one of the most successful coaches of all time, used a similar technique to encourage cooperation. He would force players to play out of position in both practices and games. Philipp Lahm, who served as captain under Guardiola at Bayern Munich, says the tactic taught his teammates “the role of the other,” the ability to see the game from different perspectives and the value of sacrifice for the greater good.

Cooperation requires that leaders and coworkers understand what the other really does.

These practices all engendered a shared sense of responsibility and a desire to work together—and may have rescued the 1999 season from defeat. In the early minutes of the 1999 World Cup quarterfinals match against Germany, a routine pass by Brandi Chastain back to goalie Brianna Scurry squirted into the US goal. On a team of me-first players, such a mistake could have broken everyone’s spirit, but Gregg and Akers remember that it galvanized the squad. Overbeck came to Chastain’s side, not to berate but to encourage. “I wanted to make sure I got to Brandi first and told her it was going to be okay,” Overbeck said. “It’s over. There is nothing you can do about it. We need you, now more than ever.”

Chastain went on to tie the game at the end of the first half. Two rounds later, Chastain scored one of the most iconic goals in women’s soccer history—the final penalty kick against China—to win the World Cup for the US in what remains the most watched women’s sporting event in history.

To be sure, the US team experienced failure, falling in the semifinals to Norway in the 1995 World Cup, for example. But it was a failure of cooperation, not a failure of talent. Recalling the 1996 team that won gold, Foudy said, “When we got on the field we were very intense, but off the field we were always pulling pranks and messing around. The year before, we had talent on the team, but we didn’t have the joy or the unity.”

Let’s be clear. Sports and business are different activities, and metaphors that attempt to connect the two are often artificial. There is a joy and camaraderie in sports that is hard to find in business. One involves play; the other, work.

But cooperation is essential—and the same—in both activities. Cooperation is less about huddling together and rallying behind the coach than it is about leaders providing a context in which teamwork and individual self-sacrifice can occur.

At a time when the structural advantages of companies and entire industries are diminishing owing to digital disruption and other forces, leaders can still rely on what they profess to be their most valuable asset: their people. Not by directing or controlling them but by unleashing their latent talents. That ultimately is the lesson of the US women’s soccer team of the 1990s.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit

Featured Insights

.