Energy transmission and distribution networks are hot commodities among investors these days. BCG’s research finds that the volume of deals in Europe has increased steadily during the past four years, reaching an unprecedented level. Likewise, the total value of these transactions has increased over the past decade, exceeding $20 billion in 2017 in Europe alone.

Investors’ enthusiasm for energy networks may come as a surprise. Many networks have single-digit returns, struggle to achieve even modest growth, and face intense regulatory scrutiny. Because efforts to boost the top line will encounter strong headwinds, investors that think they can achieve high returns without breaking a sweat are likely to be disappointed. Instead, investors should be prepared for hard work aimed at cost reduction and capex avoidance—such as improving the dispatch process for the field force, centralizing support functions, and adopting digital technologies.

Such efforts invariably pay off. In our work with energy networks to reduce costs, we have found that a well-designed and rigorously executed program is likely to achieve both opex and capex savings in excess of 25%. A share of the higher returns promoted by these savings can be reinvested in the business, enabling a virtuous cycle of improved performance and higher returns.

Increasing Deal Volumes and Valuations

To understand the landscape of energy network deals in Europe, BCG reviewed publicly known transactions from 2008 through 2017, collating data from press releases, databases, and annual reports. We focused our analysis on transactions valued at more than €100 million.

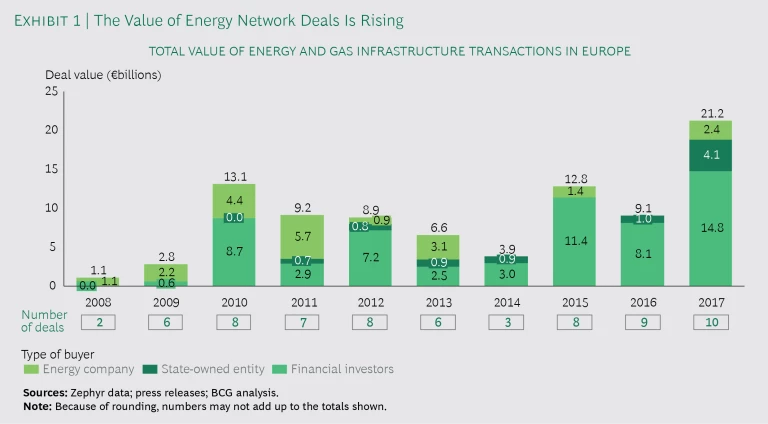

The 2008 global financial crisis precipitated a sharp decline in both deal volume and valuations. Although the deal flow never completely stopped, the return to the precrisis peak was slow. In September 2009, the European Union enacted legislation to unbundle ownership of energy assets, leading to several large transactions involving networks in subsequent years. Sales of infrastructure assets by cash-strapped countries also boosted deal volume. Even so, total deal value fell from 2010 through 2014. The market then rebounded strongly from 2015 through 2017—the latter being the biggest year to date, with total deal value exceeding €20 billion. (See Exhibit 1.)

Infrastructure finance in Europe is, on the whole, booming. The value of deals across all infrastructure sectors rose considerably in 2017 compared with 2016. In many countries, network deals were among the largest in the entire asset class, which includes transportation, telecom, and energy assets. Some examples: a consortium led by Macquarie acquired a majority stake in four gas distribution networks from the UK’s National Grid (now rebranded as Cadent) for £5.4 billion ($7.6 billion); Caisse des Dépôts and CNP Assurances acquired a 49.9% stake in RTE, the French transmission system operator, for €4.1 billion ($4.38 billion); and investors led by J.P. Morgan Asset Management acquired Spain’s Naturgas for €2.6 billion ($3.07 billion).

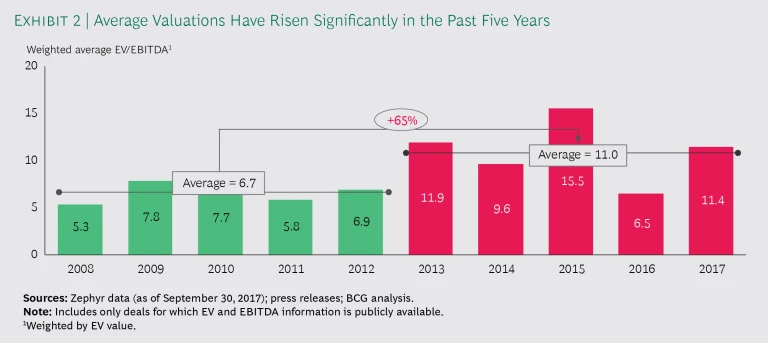

The increased demand for European transmission and distribution assets has pushed acquisition valuations higher. EV/EBITDA ratios jumped from an average of 6.7 from 2008 through 2012 to an average of 11 from 2013 through 2017. This represents an increase of approximately 65% during the five-year period, and ratios are approaching the precrisis level. (See Exhibit 2.)

Initial evidence suggests that financial investors pay more than state-owned entities or energy companies when acquiring transmission and distribution assets. From 2008 through 2017, the weighted-average EV/EBITDA for investors was 11.4, which was approximately 30% higher than deals in which the acquirer was a state-owned entity or an energy company.

Higher Valuations Increase Pressure for Higher Returns

The recent increase in dealmaking indicates that investors and infrastructure funds still believe that energy networks can provide the desired level of returns from their stable, low-risk cash flows. When valuations were relatively low and interest rates were gradually declining, investors could receive satisfactory returns on equity through refinancing and the extraction of stable dividends. Going forward, higher valuations, limited upside from additional refinancing, and a more subdued growth outlook may well require investors to generate additional value from the acquired company in order to achieve a satisfactory return on equity. That is easier said than done. Investors seeking to increase network revenues face a wide variety of challenges and opportunities, depending on the type of asset, the forces at play, and the national and regulatory contexts.

There are generally two causes for concern for transmission operators with respect to long-term demand. First, the drive toward greater efficiency in gas and power consumption is leading to lower usage per capita overall. Second, energy consumption from decentralized supplies will increase as solar and wind generation become more common and new technology makes it easier for users to generate their own electricity. Despite these challenges, transmission operators still enjoy opportunities to benefit from the need to connect large-scale renewables projects with the grid and from the continuing increase in demand for cross-border interconnections. Moreover, in some countries, goals related to decarbonizing the grid have increased the need to capture, store, and transport renewables, hydrogen, and biogases.

Investors seeking to increase network revenues face a wide variety of challenges and opportunities.

For distribution operators, long-term demand will also be affected by the lower usage per capita resulting from the overall drive toward greater efficiency in consumption. Additionally, intelligent and real-time metering will help consumers and utility companies understand, and thereby better control, their electricity or gas usage. At the same time, distribution operators will benefit from positive forces. Prominent among these is demand for new infrastructure, such as storage solutions, charging infrastructure for electric vehicles, smart meters, and smart-grid solutions.

Regardless of a network’s specific context, improving efficiency offers a clear and present opportunity to increase returns.

Investors Must Seek to Reduce Costs

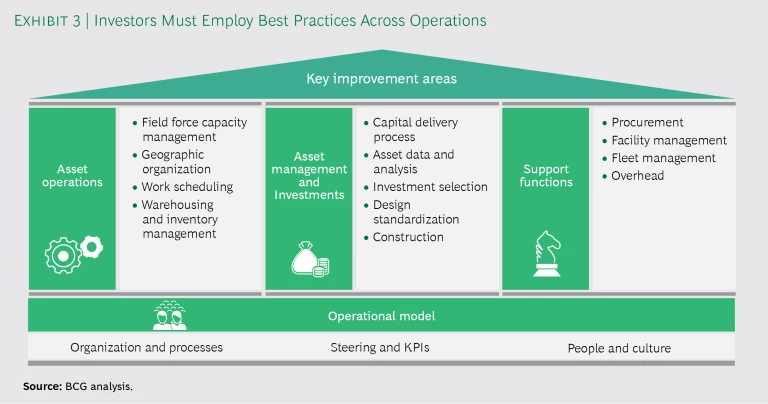

To increase EBITDA and earn the sought-after returns from their energy network assets, investors must pursue initiatives that reduce both opex and capex. They can achieve tangible and sustainable efficiency improvements by introducing global best practices and digital technology across the main areas of operations. (See Exhibit 3.) In working with leading energy networks to improve efficiency, we have seen these levers reduce opex and capex by more than 25%. The improvement potential varies considerably depending on the operations function. But in every case, a number of critical areas must be addressed.

Asset Operations. Within the broad category of asset operations, several important matters relate to the field force, including the dispatch process, organization structure, and operational effectiveness. Recent technological developments—such as advanced handheld devices, virtual and augmented reality, big data and analytics, and robotics—are enabling significant improvements in how the field force works. Dispatch processes typically present the greatest improvement opportunities, with potential savings of up to 40%. For example, leading companies have captured major performance improvements by automating the dispatch of teams. The dispatch process is monitored by standardized internal benchmarks that are produced automatically from advanced workforce management systems.

Asset Management. The use of predictive models has the potential to transform asset management by significantly reducing the volume of maintenance tasks and eliminating or reducing the need for field inspections. Leading energy networks are feeding data from both existing and new sources into analytical models that improve the performance of operational activities and reduce costs. Predictive maintenance contributes to reducing replacement capex, with potential savings of nearly 30%.

To increase EBITDA and earn the sought-after returns, investors must pursue initiatives that reduce both opex and capex.

Support Functions. Although support functions are often excluded from efficiency improvement efforts, our experience shows that a systematic review can identify significant opportunities. Many energy networks have support functions scattered across the organization that perform overlapping or unnecessary tasks. Leading companies analyze the activities performed by the various teams and use the analysis as the basis for developing a centralized and streamlined support function. Savings in procurement, overhead functions, and third-party services and materials range from 10% to 25%.

Operational Model. An energy network needs foundational enablers in its management and organizational structure to optimize operations and instill a culture focused on performance, efficiency, and continuous improvement. The adoption of a cost-conscious culture and continuous-improvement mindset enables the organization to sustain improvements generated by the other levers.

Digital Technology. New digital technologies and real-time information are essential for the successful application of these levers. Energy utilities at the forefront of digital adoption have installed smart sensors that provide continuous information from the grid. These companies also provide the field force with connected devices that enable them to work more efficiently. To manage the huge volume of data and support real-time decision making, they upgrade or replace their back-end IT systems. Additionally, they build up their analytics capabilities and partner with innovative service providers to develop new solutions in the fields of big data, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality.

Energy networks are attractive acquisitions for financial investors with reasonable return expectations and a taste for hard work. Because investors cannot rely solely on growth to extract the desired returns, they must improve efficiency to reduce costs. The good news is that cost reduction programs at energy networks are very likely to achieve the desired results. However, in-depth and tailored analyses are needed to accurately estimate a specific network’s improvement potential, and carefully planned execution is essential to reach targets and sustain the improvements. Investors that bring to bear the capabilities required to tackle the hard work that lies ahead will be rewarded with high-performing assets.