After 13 months of intense and, at times, difficult negotiations, the US, Mexico, and Canada have finally agreed to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The new free-trade pact is known provisionally as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). The new deal covers a wide range of sectors in both goods and services. But the automotive sector, which attracted the most attention throughout the negotiations, now faces the most stringent and specific new trade rules.

The impact on manufacturing supply chains for passenger vehicles and parts—not only in North America but around the world—will be significant and long lasting. In 2017, some $290 billion worth of passenger vehicles and parts were traded among the US, Canada, and Mexico. All such products will be subject to new content rules. And while the new rules are less stringent than some earlier proposals, they will mean a significant period of adjustment for the industry.

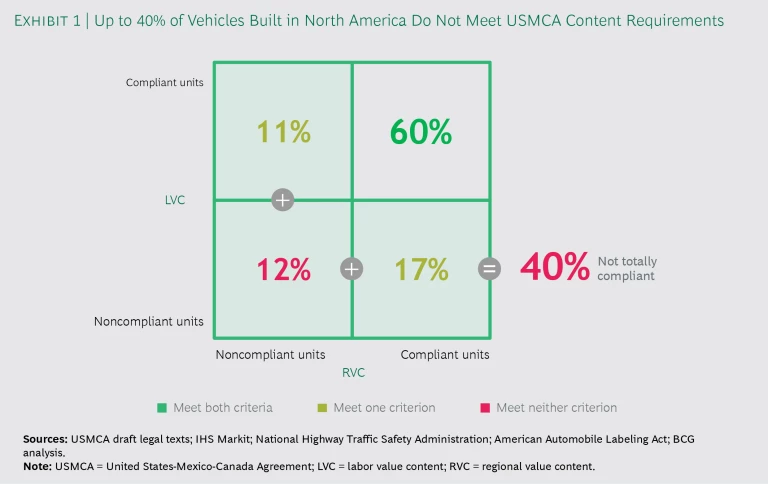

Given the confidential nature of the industry’s company cost data, it’s impossible to know precisely how much of current intra-USMCA trade does not comply with the new rules. But on the basis of publicly available data on parts content and the production locations of vehicle models, BCG estimates that, on an aggregate unit basis, up to 40% of passenger cars and light trucks currently being built and traded in North America may be noncompliant and, therefore, subject to tariffs from one or more of the three countries. (See Exhibit 1.)

Actual compliance levels of OEMs vary widely, depending on the configuration of their supply chains and manufacturing footprints. In general, however, it appears that Detroit’s Big Three automakers are better positioned under the new rules than are most European and Asian “transplant” factories in North America.

In addition, the US is actively thinking about imposing steep new tariffs on non-North American automotive vehicles and parts under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. President Donald Trump has suggested that such automotive tariffs could be set at 20% or 25%. If, as expected, these tariffs are imposed, the global automotive industry would be forced either to absorb up to $60 billion in additional costs or to pass them on to consumers in the form of higher prices. Section 232 tariffs could also be imposed on automotive exports from Mexico and Canada if they surpass specified limits. (See the sidebar “The Impact of Possible US Section 232 Tariffs on the Auto Sector.”)

The Impact of Possible US Section 232 Tariffs on the Auto Sector

The Impact of Possible US Section 232 Tariffs on the Auto Sector

The new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) trade rules could be amplified by another US trade action: the imposition of steep tariffs under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. This provision allows the US to cite national security as a basis for protecting key domestic industries. President Donald Trump has suggested that such automotive tariffs could be set at 20% or 25%.

In an earlier publication, we offered a number of trade policy scenarios for the North American automotive industry. One scenario, which combines strict new rules under a replacement for NAFTA with a US action under Section 232, we named Fortress North America. (See “ Shifting Trade Rules and the Future of North America’s Auto Industry,” BCG article, September 2018.) We estimate that under this scenario, the higher US tariffs on non-USMCA vehicles and parts would force the global automotive industry either to absorb up to $60 billion in additional costs or to pass them on to consumers in the form of higher prices. Putting this figure in perspective, an earlier BCG publication estimated the total profit pool of the global automotive industry at around $225 billion in 2017. Most US automotive imports from outside North America come from the EU, Japan, China, and Korea, which would be the hardest-hit trading partners under this scenario. (See the exhibit “More than $200 Billion in Vehicles and Parts Imported into the US from Outside North America Could Be Hit by Section 232 Tariffs.”)

Mexico and Canada have sought to avoid Section 232 tariffs by securing limited exclusions. In separate “side letters” that were released with the draft USMCA text, Mexico and Canada each obtained an exemption on shipments of 2.6 million passenger vehicle units and an unlimited number of light trucks before the additional Section 232 tariffs apply. For auto parts, Mexican and Canadian exports of $108 billion and $32 billion, respectively, will also be exempt. These de facto tariff-free quotas will have no immediate effect on Mexico and Canada: their exports of vehicles and parts to the US are currently well below these quotas. But they could eventually represent a hard cap on their car and parts exports, depending on how the North American market and supply base evolves. Because Mexico’s automotive exports to the US have been growing steadily, the impact on Mexico will be felt over time. In fact, on the basis of five-year historical growth rates, it seems likely that Mexico will hit the cap on vehicles in 2021 and on parts in 2026. Exports from Canada, on the other hand, have been flat for many years. (See the exhibit “Exported Mexican Cars and Parts—but Not Canadian Exports—Are on Track to Reach Limits When Higher US Tariffs Kick In.”)

For European and Asian vehicle and parts makers exporting to the US, higher US tariffs imposed under Section 232 would render their products significantly less cost competitive than today. Such tariffs would also significantly diminish the US as a platform for automotive export production, particularly if key trading partners such as the EU and Japan were to retaliate against eventual Section 232 automotive tariffs and impose higher automotive import barriers of their own.

The possibility of Section 232 tariffs is real, but their imposition still depends on the geopolitical dynamics between the US and its key non-USMCA trading partners, in particular the EU and Japan. Auto sector players should stress-test their businesses against this risk, proceed with no-regret moves, and prepare to adjust quickly should these tariffs materialize.

While the new USMCA is a certainty that will drive changes to operational and marketing plans, the specter of Section 232 tariffs remains a risk that automotive manufacturers must manage and mitigate. Companies will need to consider both of these trade actions as they adjust their supply base, operations, and pricing in order to gain competitive advantage.

The Impact of USMCA in North America and Beyond

The new USMCA will lead to readjustment across the North American automotive industry and affect supply chains in countries that export components and parts to North America. As OEMs and their suppliers adjust to the new rules, USMCA will create a complex compliance burden for every industry player with North American facilities.

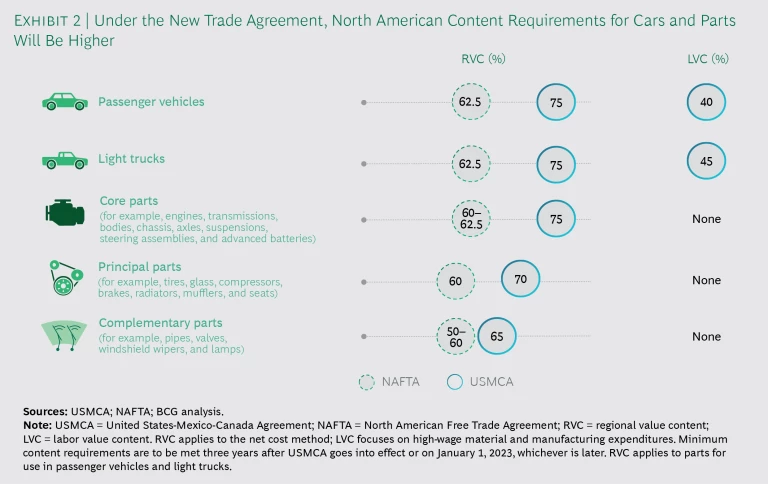

OEMs and parts suppliers will face new regional value content (RVC) rules stating that only passenger vehicles and light trucks with at least 75% of the value produced in any of the three countries will be allowed to move duty free within the USMCA zone. In addition to the vehicle-level RVC, there will be specific RVC requirements for different parts categories. For example, the RVC requirement for so-called core parts such as engines is 75%. (See Exhibit 2.)

Furthermore, the USMCA states that 70% of the steel and aluminum used in automotive production must originate in North America.(See the sidebar “How the New USMCA Auto Rules Work.”)

HOW THE NEW USMCA AUTO RULES WORK

HOW THE NEW USMCA AUTO RULES WORK

North American automotive trade policy will change markedly under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaces the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

North American Content Requirements Are Higher

Under the existing NAFTA agreement, passenger vehicles and light trucks with 62.5% of the content by value produced in any of the three countries may move among the three countries duty-free. For most automotive parts, the so-called regional value content (RVC) threshold had been 60%. To meet these requirements, the automotive industry was able to optimize its value chains freely within the NAFTA zone.

The USMCA rules are much more stringent. The RVC level for vehicles and light trucks will rise to 75%. Each of three new parts categories will have specific RVC sourcing requirements within North America: for core parts, 75%; principal parts, 70%; and complementary parts, 65%. The USMCA also states that 70% of the steel and aluminum used in automotive production must qualify as originating in North America.

In addition to the new content requirements, there is a new labor value content requirement, which stipulates that 40% of the cost of a passenger car and 45% of the cost of a light truck must be produced in locations—at vehicle assembly facilities or parts facilities—where assembly line workers earn a base pay of at least US$16 an hour. Given current supply chain configurations in North America, in many cases, the only way OEMs will be able to meet the new rules is by tracking and potentially increasing the high-wage labor value within their supply chains.

Exemptions and Phase-In Periods Have Been Provided

The new rules will apply to passenger cars and light trucks, as well as their parts and components. The new rules for heavy trucks are also more stringent than those of NAFTA, but they are not the same as those for passenger cars and light trucks. According to the draft USMCA texts, the RVC rules for passenger buses that can carry more than 16 passengers, three- and four-wheeled motorcycles, motor homes, and off-road vehicles will be similar to existing NAFTA requirements. The new content provisions for vehicles and parts will be phased in over three years, along with some provisions for flexibility. This means that, in some cases, the phase-in periods will be shorter than the life cycles and capital-investment-planning horizons for specific vehicle product lines.

Noncompliance Tariffs Vary by Country

Under NAFTA, the penalty for noncompliance with the RVC rules was the application of so-called most-favored-nation tariffs that the US, Canada, and Mexico committed to as members of the World Trade Organization (WTO). For passenger vehicles, the US will apply a 2.5% tariff, Canada, 6%, and Mexico, 31%. The US tariffs on auto parts under the WTO are generally lower than 2.5%. It should be noted that while some of these tariffs may seem low, OEMs and parts suppliers still chose to optimize their supply chains around them under the former NAFTA regime. The USMCA does not itself raise noncompliance tariffs, but if the US moves forward with its Section 232 tariffs, the penalty for noncompliance would be very material.

Beyond the RVC requirements, the USMCA includes a new labor value content (LVC) requirement stipulating that 40% to 45% of the cost of a vehicle’s assembly and components must come from facilities where workers earn at least US$16 per hour. Labor leaders in all three countries have broadly supported this provision. But some analysts have observed that the LVC may have second-order effects, such as influencing decisions regarding the tradeoffs between automation and high-cost labor. Automotive manufacturers across the value chain will need to evaluate their compliance with these new rules on a product-by-product basis.

Although many vehicles currently being built and sold in North America already meet the duty-free status requirements, many don’t. In addition, depending on labor costs in the facilities in which they are produced, certain parts that meet the RVC requirement might not meet the LVC requirement.

As a result, compliance with LVC rules will require full transparency along the value chain, including tier two and tier one suppliers as well as OEMs. In a world in which many suppliers are not ready to disclose the specifics of their material, labor, and overhead costs, getting their hourly labor cost data on a plant-by-plant and product-by-product basis will be a huge challenge. The new rules will require industry participants to develop new competencies and a completely new way of collaborating. OEMs and suppliers alike will need to build skills in advanced trade rules–based supply chain management.

European and Asian companies that supply parts and vehicles to North America will be significantly affected. There will be a natural tendency to shift some production to North America in response to the higher USMCA content and labor rules. Given the wage rate environment in the three countries, the LVC requirement will handicap Mexico as a sourcing location.

Every company in the automotive sector will need to understand how—in terms of its specific value chain and product mix—it is positioned under these new rules. Furthermore, companies must assess, in light of the new rules, not only their own manufacturing and component-sourcing footprints but also the impact on their competitors. This competitive lens may expose relative cost risks for manufacturers, as well as opportunities for others to go on the offensive and try to take market share or raise prices.

Different Players Will Be Affected Differently

Each company now needs to examine its own position—as well some general effects that we expect—relative to where it fits in the value chain:

- OEMs with Assembly Facilities in North America. OEMs need to understand their value chains in greater detail than ever before. Because sourcing, operations, and distribution will all be affected by the new rules, OEMs need to analyze each product line, considering each one’s competitive position relative to key rivals in each segment. Over time, rising domestic costs resulting from the new content rules may also affect the competitiveness of North America as a platform for serving overseas vehicle and components markets.

- Tier One Suppliers with North American Facilities. OEMs now require complete visibility into their tier one suppliers’ RVC and LVC. With this visibility, OEMs will seek supplier sourcing locations that can help them achieve their own RVC and LVC requirements under the new rules. Given the high levels of capacity utilization across the automotive industry and the tight US labor market, tier one suppliers will need to revisit their business plans and prepare their negotiation strategies. Any tier one supplier with underutilized capacity in high-cost facilities stands to benefit from the OEMs’ drive for RVC- and LVC-compliant sourcing, assuming, of course, that the overall landed-cost economics are competitive.

- Tier Two Suppliers in the US and Canada. This is one group that stands to gain. Many tier two and other suppliers farther back in the value chain may see an increase in orders as the pressure to meet the new LVC requirement cascades from OEMs to tier one suppliers to tier two suppliers that pay workers more than US$16 an hour. To capture market share, these companies will need to secure production facilities, materials, and labor to ensure a smooth ramp-up in terms of quality, delivery, and cost.

- OEMs and Tier One Suppliers Serving North America from Overseas Facilities. In the NAFTA renegotiation, the Trump administration’s goal was to bring auto and other industrial jobs “back” to the US. Over time, the USMCA’s higher RVC and LVC requirements will tend to drive resourcing of components and parts to North America, specifically to high-cost facilities in the US and Canada. This trend will accelerate in the event that the US decides to impose higher tariffs for noncompliance through a Section 232 or other trade policy action.

Three Actions Auto Industry Leaders Can Take

To mitigate risk and seize opportunities, CEOs should heed the following imperatives:

- Assess the impact on sourcing and the supply chain. Automotive companies need to review component sourcing through two lenses. First, they must consider the origin—the national source of a component. Second, they must know the LVC, and, to determine this, they must obtain information on the wage rates embedded in different components and subsystems from different suppliers and their subsuppliers. To ensure the best and least risky sourcing options, companies will need to assess typical procurement criteria such as cost, quality, and delivery, along with RVC and LVC considerations, on a component-by-component basis.

- Evaluate industrialization strategies and capital expenditure plans. Companies now need to consider how well their industrialization strategies stand up to the new trade rule criteria and whether previous strategic and operational decisions still make sense. In particular, previous capital expenditure decisions—especially those not yet implemented—should be reconsidered in light of the new trade rules. From a compliance perspective, procurement, supply chain, and operations leaders need to ensure that their supply base management information systems—be they IT based or manually overlaid—can provide the information required to withstand customers’ and government officials’ periodic audits.

- Consider the revenue side too. The new trade rules will increase costs for specific products and possibly lead to price increases as manufacturers seek to protect profit margins. For some manufacturers, costs may not increase for certain products, while for their competitors, they will. Such situations might result in price realization opportunities. Ultimately, higher prices will dampen demand. For this reason, it will be critical to analyze the impact of the new rules on individual product lines.

The impact of the new USMCA will be felt in North America and will ripple across the automotive industry worldwide. The complexity of the new North American rules—combined with the looming specter of US tariffs under Section 232—demands that, to remain competitive, each industry player conduct a thorough value chain assessment and adjust its sourcing, footprint, and pricing. The new trade rules under USMCA are now known, and industry players can optimize their individual situations. Preparing for possible Section 232 tariffs requires a parallel set of actions to manage risk and volatility.

None of these are business-as-usual activities: the information required for such an assessment is not normally tracked and managed in the industry. Understanding the competitive environment and the implications, moreover, adds a level of complexity and imperfect information to the process.

The difficulty of the task may cause some companies to shy away from conducting this analysis and to decide simply to wait and see what happens. But we believe that companies that move swiftly to seize the opportunities and mitigate the risks will be positioned best to secure advantage over the long term.