In most news coverage about the private equity industry, one question recurs: After two decades of strong growth and high returns, is the industry overheating?

Several indicators—including deal multiples, leverage ratios, and the amount of dry powder (that is, uninvested capital)—are at historically high levels, and new entrants continue to flood into the market. But we believe the PE industry still has significant room to grow. A clear-eyed view of the data reveals that the proportion of PE-backed companies remains low, that PE ownership generates superior returns relative to other asset classes, and that firms have continued to deploy capital despite record funds flowing in.

That said, continued growth does not mean business as usual. As in all market cycles, corrections and disruptions are inevitable. Further, the playbook that PE firms have traditionally employed—creating value mostly through financial engineering, acquisitions, and tactical operational initiatives—is, albeit effective, no longer sufficient. Increasing competition, high deal multiples, and—the biggest disruption of all—digital technology all require firms to change their value creation approach. Moreover, the founders of many of the biggest and best-known firms are starting to retire, which will mean a changing of the guard. In this environment, firms must rethink organization design, double down on digital technology, and revamp their approach to talent.

Troubling Numbers

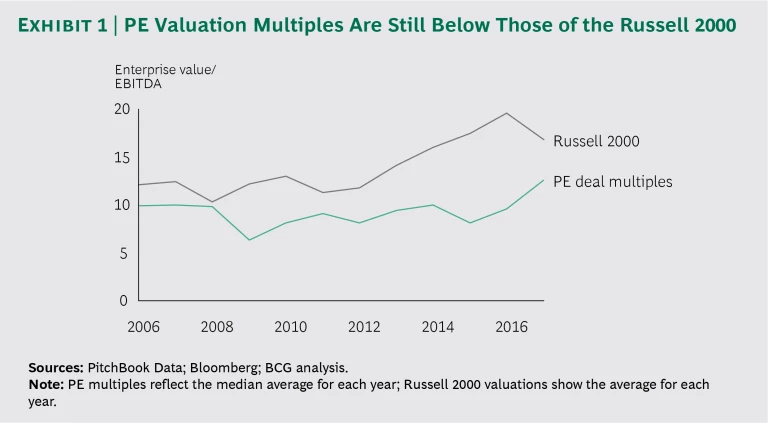

To be sure, naysayers’ concerns are understandable. By many measures, the industry continues to grow extremely fast, and trees don’t grow to the sky. Average deal multiples in the US rose dramatically in 2017, to roughly 12.5 times EBITDA, according to PitchBook Data. That is higher than the previous all-time highs, which were reached prior to the financial crisis. Leverage ratios, at five to six times EBITDA, are similarly concerning, as they signal a vast upswing in the number of investors searching for yield.

Indeed, strong returns for the industry have drawn new entrants, which all compete for deals and push up multiples, making it that much harder to sustain high returns in the future. As of January 2018, a record 2,296 private equity funds were active in the market, seeking to raise an aggregate $744 billion in capital—a 25% increase compared with January 2017. At the same time, the amount of dry powder among buyout firms remains at record levels: $628 billion as of the end of 2017.

As money continues to pour in from institutional investors, firms will have a tougher time finding deals that meet their performance criteria. Many of them will rely even more heavily on secondary buyouts, which has the effect of slowing down penetration growth and making value creation even more difficult.

Significant Room to Grow

Despite the negative indicators, we have a positive outlook for growth, and investors do too. (See “Three Ways That the PE Model Creates a Unique Advantage.”) PE valuations are certainly high, yet firms in the aggregate still pay less for assets than the public markets. Exhibit 1 shows buyout multiples compared with Russell 2000 multiples.

Three Ways That the PE Model Creates a Unique Advantage

Three Ways That the PE Model Creates a Unique Advantage

A December 2017 Preqin survey of PE investors shows just how much optimism there is regarding private equity as an asset category. Among respondents, 63% have a positive perception of the industry, and 53% plan to increase their allocation to private equity in the longer term.

The main cause of that optimism is that the PE model creates an advantage for investors, in three ways:

- The governance structure of firms under PE management is superior to that of their public counterparts, which have less tightly aligned incentive structures and the constant distraction of quarterly performance requirements.

- PE firms’ great advantage is time: investor money is locked up for years, so firms can wait for the ideal moments to buy and sell companies in order to cash in. In a world that is characterized by the increased number and intensity of disruptions, the flexibility of the PE ownership model means that PE firms are best positioned to navigate and thrive when inevitable shocks appear on the horizon.

- As markets become more interconnected worldwide, large PE firms have the advantage of broader market intelligence, which can generate insights across asset classes, industry sectors, and geographic regions. As a result, they can strike deals that capitalize on such insights.

Of course, investors are also happy with the relative outperformance of PE investments compared with those in public equities. Private equity outperformed stocks by 9% in Europe and 4% in the US over the last 20 years (although the gap is narrowing). In sum, there is significant money in private equity—and more flowing in each year—but one can’t make the case that it has peaked as an asset class.

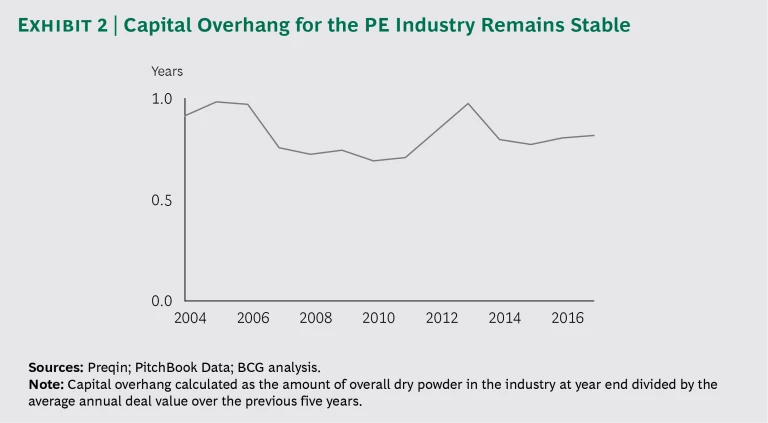

Even factoring in the currently high levels of dry powder, the industry is still managing to deploy capital at a record rate ($1.18 trillion worldwide in 2017, up from $1.13 trillion in 2016). (See “Finding New Deal Sources.”) Consider capital overhang, or the amount of time it would take at current deployment rates to invest every dollar that PE firms now hold. As Exhibit 2 shows, the current overhang level sits at about one year, roughly where it has been throughout the last decade.

Finding New Deal Sources

Finding New Deal Sources

As the market grows more crowded and the competition for deals intensifies, PE professionals are getting creative about increasing the supply of assets in the market. To source deals, some are using digital tools such as natural-language algorithms that can analyze unstructured data like customer reviews to identify rising brands with passionate consumers. (See “ Digital Deal Sourcing in Private Equity,” BCG article, September 2017.)

PE firms are also being creative about approaching new targets. For example, they are taking minority positions in smaller, founder-owned companies. Other PE partners are employing creative approaches to build trust with reluctant owners, such as bringing in operational talent, particularly to support digital transformation, which could lead to buyout opportunities later on.

And firms are seeking ways to capitalize on changes in the US tax code. Some firms now have a plan in place to systematically conduct a new round of due diligence—and potentially new investment—on holdings at the two-year point, as part of a larger assessment of whether to sell at the three-year mark (the new threshold for profits on a holding to qualify for long-term capital gains). In addition, some firms are now partnering with companies in search of carve-out opportunities, as asset sales have now become more attractive. (See “ The Impact of US Tax Reform on Corporate Strategy and M&A,” BCG article, March 2018.)

Another positive metric is the portion of the economy controlled by PE firms. Looking only at the US, the number of companies owned by PE players surpassed the number of publicly owned companies back in 2007, and that split has been growing ever since. Considering the value of the companies in both categories, however, PE-owned entities are far smaller—just $862 billion in implied value as of 2016, compared with $27.4 trillion for all public companies (including huge entities such as Apple and Facebook).

Breaking down the universe of PE-owned companies by size shows a similar story. Midsize companies (those with $500 million to $1 billion in annual revenue) show the greatest rates of PE ownership, but even then the penetration rate is only 17%. Even if the industry was to deploy all its dry powder tomorrow, that penetration rate would increase to just 27%. For companies with $1 billion or more in revenue, the penetration rate would be only 20%.

Similarly, using GDP as a baseline shows that the PE industry has a good deal of room to grow. The US is the most developed PE market, but just 1.6% of US GDP is owned by PE firms. Australia has the second-highest penetration level, at 1.1%, and no other country has more than 0.5%. Simply getting the rest of the world up to the level of the US represents a massive market opportunity.

Most PE professionals would tell you that the assertion that there is more room to grow feels at odds with the reality they are living and breathing every day. And they are right. This is the most competitive market that private equity has ever seen. Nevertheless, while we acknowledge this contradiction, the overall trend in the industry is toward growth.

Business as Usual Is Not Enough

Many firms are extremely good at creating value and driving change in their portfolio companies, but are far less rigorous in the playbooks they apply to their own internal operations. (See “ Capitalizing on the New Golden Age in Private Equity ,” BCG article, March 2017.) Moreover, a critical forcing function in the industry is the changing of the guard taking place at many of the best-known firms, as founders begin to retire. This creates an unprecedented opportunity for firms to modernize themselves. The new generation of leaders will be able to reexamine everything from the firm’s operating model to its investment approach, career paths, incentives, and critical skill sets. In contrast, firms that simply hand over the keys to a new senior team—and leave outdated thinking and processes in place—risk wasting this opportunity.

In an increasingly competitive industry, firms must change how they operate, in three key ways.

Rethink organization design. PE firms have to rethink how they organize themselves to accommodate their precipitous growth over the last ten years. Many firms have made some changes, but most have not gone far enough in adapting their internal operating models. This is creating inefficiencies in their organization and tensions among their most senior ranks. Instead, firms will need to address three aspects of organization design.

First, they need to organize themselves with the right balance of sector expertise and more thematic investing strategies. It’s a difficult needle to thread. Given the current level of competition in the market, firms with sector-specific insights can identify targets and win deals over firms that still apply a generalist model. Yet as industry boundaries continue to blur, looking at sectors in isolation can create blind spots. A similar concept applies to sourcing deals in new areas (such as minority positions, activist mandates, and truly patient capital), or looking beyond defined asset classes (such as equity or credit) to more hybrid opportunities. Firms will need to explore these opportunities, yet they must put the right organization structure in place. Otherwise, good deals that don’t fall explicitly into any one group’s mandate will fall through the cracks.

Second, there is the question of internal processes. Growth magnifies inefficiencies, and as the firms grow across countries and into new asset classes, they need to adapt their processes—such as deal prioritization, staffing, and deal governance—accordingly. Processes that may have previously been run in an informal way now require much more formal mechanization to keep on track at scale.

Third, PE firms should adapt decision-making rights and determine accountabilities across the firm. In 2006 and 2007, we saw funds scale up very fast without adapting their operating model, which resulted in some disastrous deals made at the top of the market. To avoid these mistakes and resist the urge to deploy capital no matter what, firms will need to stay disciplined regarding decision-making processes and accountabilities.

In short, each PE firm will need to find the scalable operating model that fits with its heritage.

Double down on digital technology. PE firms have generated strong returns for decades by cutting costs and improving operations at portfolio companies in order to boost margins. Today, those baseline measures still work, but they are no longer enough to differentiate PE firms. Instead, the top performers are bringing digital expertise to their investments to help companies rewire themselves, develop new products and services, better meet customer needs, and generate top-line growth.

Many of the owners at target companies understand the need for digital transformations in their businesses, but they lack the relevant expertise, time, and capital to launch a transformation. And they don’t want to learn through trial and error. If PE firms can develop a value proposition regarding digital—such as helping companies digitize their supply chain or improve their go-to-market processes, both of which enable them to better meet customer needs—they are far more attractive as buyers, and they will be far more successful in terms of unlocking new value.

Revamp the approach to talent. Firms must develop a holistic talent strategy that considers carefully which essential skills need to be in-house and which are best accessed through a constellation of external advisors. As value creation becomes more difficult, cutting-edge specialization becomes more important, and few firms will be able to retain in-house staff to cover the full breadth and depth of topics required to succeed.

But PE firms are increasingly reluctant to outsource certain skill sets: data scientists, macroeconomists, and consumer insight specialists. As the value creation playbook shifts from financial engineering to operational improvements to digital transformation, these skills are becoming must-haves. The greater emphasis on up-front analysis is another reason to have these skills in-house, to ensure that firms have the macro and consumer trends quantitatively nailed down well before considering value creation on any particular investment.

The PE industry has not peaked. PE-owned companies are dwarfed by those that are publicly traded (a ratio of 30 to 1 in the US), and LPs continue to invest their capital in private equity, whose returns exceed those of other asset classes. All of these factors point to continued growth. Clearly, with equity multiples as high as they currently are, some sort of correction is likely. The fundamentals of private equity are strong, however, and we believe the industry will withstand any potential disruptions and emerge stronger than ever.

Yet the successful firm of the future will look nothing like it does today. Funds need to rethink how they organize themselves and strike the right balance between narrow expertise in a given sector or region and thematic approaches. They also have to apply digital to their own operating model and to the companies in their portfolios, and they must put the right talent in place. These initiatives require firms to invest in the future and remain optimistic that the industry’s best years are ahead of it, rather than behind.