Like many retailers, traditional grocers see massive dislocations all around them—new competitive pressures, growing technological complexity, difficulties in the integration of online and offline operations, and the need to alter store formats to attract and retain customers. Recognizing these challenges, grocers are working hard to sustain and improve sales and margins.

They also know that they need to fundamentally transform their operations if they are to navigate through these dislocations. So far, however, many grocers have focused on incremental change within each function, while hesitating to make the bold moves essential for long-term success. Most are preoccupied with narrowly defined optimization projects within functional silos, such as supply chain, store labor, and waste reduction, rather than undertaking cross-functional and transformational projects.

Given the pace and magnitude of dislocations in the sector, fundamental change is necessary. Traditional grocers need to undergo a customer-centric transformation that resets their operating and service models, focusing on end-to-end (E2E) changes that deliver the right customer experience at the right cost . Such a reset of customer-centric operations typically enables companies to reduce their labor costs by an average of 5% to 10%, lower their inventory costs by 10% to 20%, and cut waste by 10% to 30%. Grocers that adopt this approach will improve their operating margins by 1% to 3%, which translates into billions of dollars sector-wide that they can reinvest in price, service, customer experience, and other competitive advantages that are critical to their survival.

A Path to Transformational Change

Over most of the past decade, large grocery supermarkets—particularly those operating in developed markets—have suffered from stagnant topline sales growth and a steadily rising cost of doing business, resulting in disappointing profitability and shareholder returns.

We expect these trends to continue or even accelerate over the coming decade, given new competition from lower-cost competitors. Among these competitors are discount, club, and dollar stores, and disruptive players such as Amazon (with its foray into food sales) and Uber (with its Uber Eats online meal-ordering and delivery service). Emerging technologies may lead to further disruption in the way grocery stores operate and perhaps even in their value proposition. Moreover, customers’ expectations continue to rise—both on their own and in response to these disruptive trends—forcing grocers to make costly changes to their operations in order to stay relevant.

In light of this unsettled environment and outlook, engineering the process to remove non-value-added tasks is a strategic imperative for all traditional grocery businesses. Such engineering will also provide the platform to drive additional fundamental change as emerging technologies become more mature and robust. Unfortunately, most traditional grocers find themselves ill equipped to tackle this challenge, for several reasons:

- Many grocers tend to frame objectives with reference to productivity and cost takeout instead of meeting customers’ needs and improving their experience.

- The organizational structure of most grocers encourages optimization within functional silos. Often, grocers lack the governance structure necessary to make tradeoffs across functions to optimize processes end to end and to improve customer outcomes.

- Many grocers fail to manage change effectively. They don’t validate and refine solutions prior to rollout; and in rolling out change, they rely on simplistic central communications.

- They struggle to make change stick in the long term. Few grocers have embedded new ways of working in daily store operations or created a continuous improvement mindset that empowers employees to own the change effort.

In responding to these challenges, grocers need to pursue difficult and ambitious goals, resetting the operating and service model to focus on E2E changes that provide the right customer experience at the right cost. Targeted improvement efforts—such as reducing total loss—can still generate significant value. But grocers can unlock substantially more value by integrating their business strategy and customer value more thoroughly than by addressing any one element independently.

Not only will these E2E process improvements free up resources for reinvestment in price and service, but they may also align the organization across functional areas to deliver customer value more consistently. To this end, some grocers already are pursuing a customer-centric operations reset. The approach comprises three critical strategic steps: identifying what customers truly value; reassessing and redesigning the E2E operating model; and making change stick.

Identifying What Customers Truly Value

When grocers reset their operating processes, they need to make the customer the starting point. Before proceeding to any other step, the grocer must understand what the customer values and is willing to pay for and, ideally, how the grocer can differentiate itself and build loyalty.

It is important to avoid defining customer value too broadly or superficially. The definition must be sufficiently granular—by department or category—to be actionable and operational. For example, many retailers say that their customers prize “value” or “a high degree of choice.” But these concepts are too broad and vague to translate easily into concrete supportive action, and they are even less helpful when applied storewide.

In reality, customer expectations are not uniform across the entire store; rather, they differ by department, store area, and specific customer shopping mission. Understanding the differences can help grocers focus their investments. For example, a grocer might learn that customers of its in-store bakeries prize “fresh out of the oven,” with “the best crust,” and “from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.” These are tangible goals that grocers can tie to specific processes and actions.

Reassessing and Redesigning the E2E Operating Model

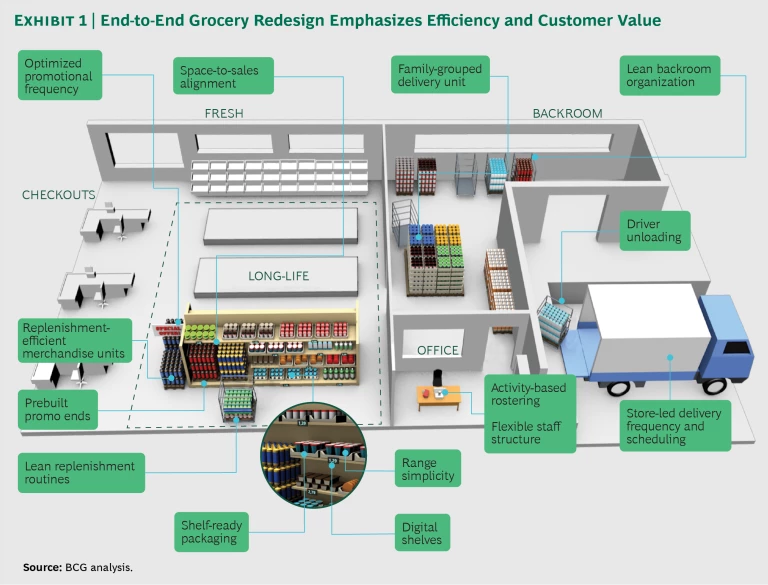

After articulating the customer value proposition, the grocer must pursue E2E process excellence to consistently deliver the specified customer value. (See Exhibit 1.) This includes assessing all processes and departments in detail to identify current operating costs and cost drivers; establishing a baseline of current delivery-of-service levels and customer value; and then considering key cross-functional tradeoffs to better deliver value. Sometimes the goal may be to delight and attract customers (for example, by offering fresh-baked goods from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.), and other times the focus may be on eliminating waste and reinvesting the savings in the form of lower prices or improved service. To pursue E2E product excellence, grocers should adopt several key measures.

Set ambitious goals. To pursue and maintain E2E process excellence, leaders need to set ambitious top-down aspirations that drive employees to think big. We suggest that senior leaders set up a “shadow board” composed of high-performing individuals from each major function—for example, merchandising, space management, replenishment, logistics, and store operations. Leaders should empower this oversight board to approve solutions, manage tradeoffs, and spur healthy competition among different areas of the company to achieve ambitious goals.

For example, a leading European grocer implemented a customer-centric operations reset to reduce replenishment inefficiencies resulting from SKU proliferation that had increased search and handling times—and thus raised replenishment costs—along the entire supply chain. Because SKU proliferation had maxed out the grocer’s shelf space, introducing more replenishment-efficient merchandise was unduly difficult. To make matters worse, customers found the abundant product selection confusing rather than appealing.

To address these issues, the retailer created a cross-functional team and assigned it the task of conducting an E2E reset for all categories. The team reviewed the grocer’s assortment strategy, streamlined the offerings, reduced the number of SKUs while selectively listing new products, established a better and clearer assortment structure based on customer needs and optimized planograms, and negotiated with suppliers. The team also improved the grocer’s replenishment efficiency by, for example, using more shelf-friendly packaging, display pallets, or dollies. As a result of these changes, the retailer increased customer satisfaction scores, increased category sales by single digits, improved gross margins significantly, and reduced E2E operating cost from the distribution center to the store by double digits.

Embed lean principles. E2E process excellence requires embedding lean tools and principles of continuous improvement in day-to-day activities. These principles include relentlessly distinguishing between value-adding and non-value-adding activities (that is, waste), striving for standardization and consistent execution, and building a culture of continuous improvement by empowering employees and partners to identify problems and improve their work environments.

Tap emerging technologies. New technologies provide a means to redesign the operating model. Consider the checkout process. Many shoppers view this process, with its slow queues and manual scanning, as a major annoyance—and the checkout process often represents 30% or more of total store labor costs. New technologies are zeroing in on this non-value-adding activity, making unattended checkout solutions available. But unattended checkout merely scratches the surface of potential technology-enabled solutions. Other possibilities include using in-store robotics for inventory management and customer service processes, introducing in-store replenishment systems, applying advanced analytics in automated replenishment systems, automating warehouse operations, and installing intelligent sensors.

Align mindsets and behaviors. In order for a complex change effort to succeed in the long term, a grocer must take concrete steps to align the organization’s mindset and behaviors with the new goals. Examples include ensuring that the new processes become the standard way of working, confirming that day-to-day activities support the new processes, aligning governance and incentives with the new processes and goals, investing in training, and making sure that the management team is setting the right example.

Many grocers could improve their E2E processes by better aligning performance management systems across the enterprise. For example, one retailer rationalized its suite of scorecards from 20 to a single, shared scorecard containing five KPIs, thereby sharpening everyone’s focus on enterprise-wide E2E goals.

Making Change Stick

Even when grocers understand the specific actions they must take to simplify their operating or service model and to lock in ROI improvements, they may struggle to implement lasting change, given the multitude of tasks, the complications associated with staff turnover, and the complexity of distribution center and store networks. Nevertheless, companies that reset operations with a customer-centric mindset are in a better position to execute the redesign because they carefully test and refine new policies and procedures, create momentum, and scale up the change.

Many changes require a store-led approach, though others require either a category-led or distribution-network-led approach. (See "Case Study: Store-Led Change Management.") The store-led change approach is most suitable for actions that must occur store-by-store—such as the inculcation of behavioral changes that are necessary for implementation of specific new store processes, or efforts to persuade employees at the individual stores to embrace broad change initiatives.

Case Study

Case Study

For an example of store-led change management in action, consider the experience of a major grocery retailer. Customers were growing more and more dissatisfied with the quality and freshness of the grocer’s products, contributing to stock losses of more than 25% year-on-year. Senior leaders understood that curbing these losses was critical, but they struggled to effect change at individual stores.

To institute the necessary changes, the company decided to adopt a store-led change management program. The grocer began with a short, rigorous diagnostic to identify the root causes and scale of the problem. Next, it defined a few big solutions, piloted them in a single store, and then cascaded the initiative—first to 23 stores, then to 230, and onward. This rollout enabled the company to involve leadership teams across the network and rapidly test, refine, and validate solutions (which included ensuring that the solutions were scalable). Store teams then visited one of the pilot stores, and coaches helped individual stores embed the desired behaviors and new ways of working.

Using lessons from the initial store’s rollout, the grocer developed a 12-week structured program, with fixed timelines specifying daily and weekly activities and multiple milestones to ensure progress.

The company fostered team engagement by framing the goals of the program as being to improve the freshness of products for customers and to make employees’ work easier by simplifying and accelerating the markdown process. To encourage engagement, the stores created a community of change on Google+, celebrating successes and sharing tips and issues.

From the beginning, senior leaders also offered visible support to the stores. For example, the grocer determined in the initial diagnostic that stores were the root cause of about half of the quality and freshness problems, but that the other half originated in upstream areas. So the retailer’s leadership announced forcefully and clearly that the initiative was a cross-functional effort and that upstream functions would support the in-store efforts.

After just one year, these store-led change efforts yielded significant improvements in the 300 stores that graduated from the grocer’s 12-week program. Individual stores saw reductions in stock loss of 20% to 50%. Overall, the retailer cut losses by about 30%, improved product freshness, and increased customer satisfaction. It also established a method for rolling out future operating changes.

Using a single store to pilot a particular solution is an effective way to test and refine the solution and demonstrate its value. For example, some grocers use rapid prototyping via “hothouses” or “the transparent store” to test and refine E2E optimization. This involves monitoring multiple variables, including sales, availability, hours, and product movement. Prototyping and mini-testing new processes in-store with clients and cross-functional teams can create a fast feedback loop that the grocer can use to fine-tune and quickly adapt the solution before undertaking broader testing.

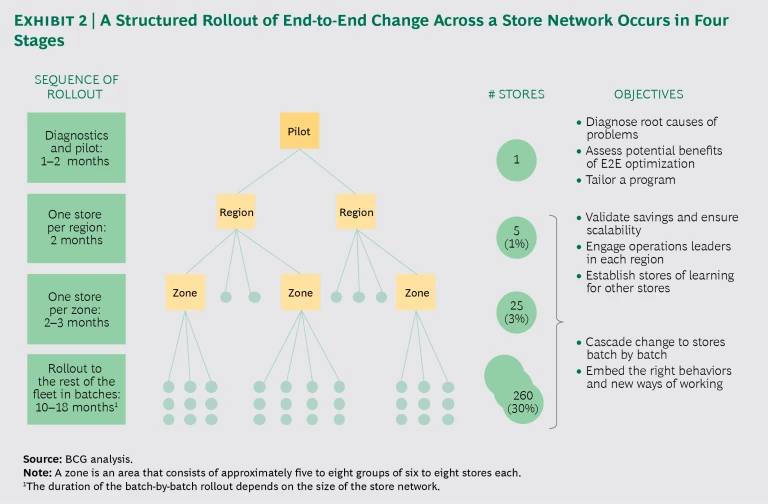

Once perfected, a solution can move to several regional stores that serve as training facilities for an even wider rollout. (See Exhibit 2.) Representatives from other stores can visit these hubs, observe the changes first hand, and hear directly from their peers before implementing changes at their own stores.

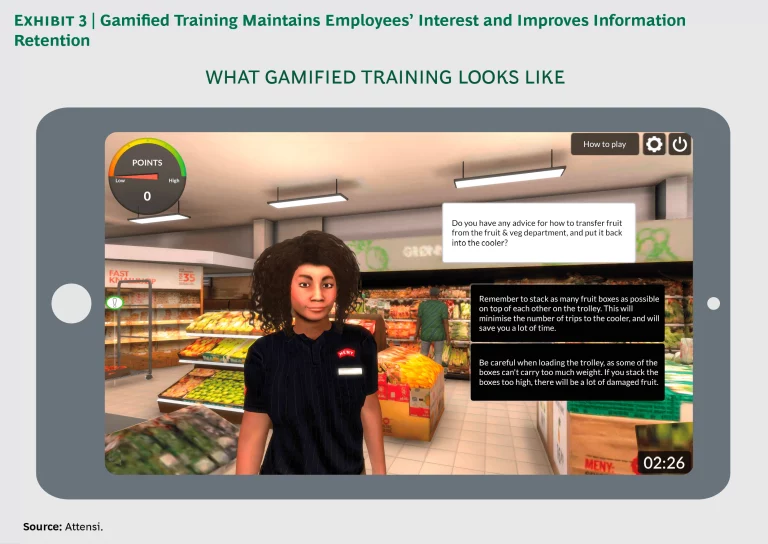

Part of this training may include innovations such as advanced gamified simulation training, which differs from classroom training and traditional e-learning. (See Exhibit 3.) Grocers can tailor simulated training to their store format and value proposition, and create realistic in-store scenarios. This can help them roll out standards more consistently, measure results, and conduct appropriate follow-ups.

Making change stick for the long term depends on three additional elements:

- A Structured Program. Grocers should break the process down into discrete, manageable tasks. By clearly defining goals and deadlines from the outset—ideally with specific actions for each day or week—leaders can celebrate progress with their teams at regular intervals, building enthusiasm, instilling the right behaviors, and giving management a handy way to monitor progress.

- Team Engagement. To build team engagement, grocers need to articulate the benefits of the change effort clearly and in ways that resonate well with their teams—for example, by detailing how customers will benefit and how their own work experience will improve. By encouraging friendly competition, leaders can build a community that supports and strives for change.

- Visible Support. To convince employees that the change effort is a priority and not just a temporary productivity project that will soon fade in importance, leaders need to communicate its priority clearly, loudly, and often. They should also make clear that the reset is a team effort. This may entail explaining how, for instance, upstream functions will improve their processes while in-store teams improve theirs.

Many grocers are planning to move beyond the narrowly defined optimization projects of the past to attempt more ambitious E2E projects for fundamental, cross-functional change. Admittedly, these projects are complex, and companies in the past have often been frustrated in their efforts to complete them successfully. But some leading companies are finding success by pursuing a customer-centric operations reset. By focusing on the customer, implementing E2E optimization, and taking steps to make change stick, these companies are successfully aligning a customer-centric strategy with day-to-day activities while upgrading productivity.