While it’s unlikely that Russia will soon return to the booming growth it once enjoyed—back when the ruble was strong and oil prices hit record highs—the economy today shows signs of stability following the financial crisis of 2014-2016. In fact, many Russians are ready to spend more than they’ve done in the past on goods and services that matter most to their quality of life.

At the same time, however, the financial crisis left its mark on Russian households—personal finances are tight and inflation has outpaced income growth. As consumers adjusted over the past decade to that new economic reality, they’ve grown more cautious, pragmatic, and value-conscious.

Yet substantial opportunity abounds in this still-critical emerging market, especially for global companies that understand the nuances and needs of Russia’s complex consumer economy. Despite its serious economic pressures, Russia remains a market of 147 million people with per-capita income around one-third higher than China’s. And although much of this vast, dispersed nation has some traits of a developing country—such as outdated infrastructure and insufficient health care—its consumers exhibit characteristics of buyers in more mature economies.

To understand the spending priorities of Russian households—and how consumers balance savings, economy, and consumption—The Boston Consulting Group’s Center for Consumer Insight (CCI) has tracked the nation’s consumers for more than a decade. During that time we conducted two surveys, in 2013 and again in 2017. In our recent study in 2017, we surveyed nearly 4,000 consumers of different age groups, occupations, and income levels across the country. We asked about their outlook for the future, their spending plans for the year ahead, and the factors they consider when making a purchase. Comparing their answers with results from our 2013 survey revealed how much Russian consumers have reset their expectations since the financial crisis and how sophisticated they’ve become at the art of consuming what they want within their means. Other findings include:

Russians have reset their expectations since the financial crisis.

- Although Russian consumers are less optimistic than before the financial crisis, they are also less anxious. Fifty-five percent say they are hopeful about the future, a sharp decline since 2013 but around the same level as in many advanced economies. While 72% of consumers say they worry about the future, that percentage was higher in 2013.

- While most Russians are cutting back on goods they perceive as nonessential, such as alcohol and ready-to-eat foods, nearly half intend to spend more in product categories they regard as important for health and the well-being of their families, such as fresh foods, education, and travel.

- Russia’s once-strong devotion to famous brands is fading. Only 24% say that brands are a good reflection of themselves or their values. But consumers still think brands are important in certain categories, such as digital media, electronics, and retail.

These findings suggest that companies need to approach Russia differently than they have in the past. They should develop more sophisticated, customized product and go-to-market strategies and a deeper presence on the ground. In this report, we examine how Russia’s new economic reality is influencing consumer behavior, and where consumers say they intend to spend more and cut back. We also explore how Russian consumer sentiment is likely to affect three important industries: health care; travel and tourism; and automotive.

Coming to Grips with Economic Reality

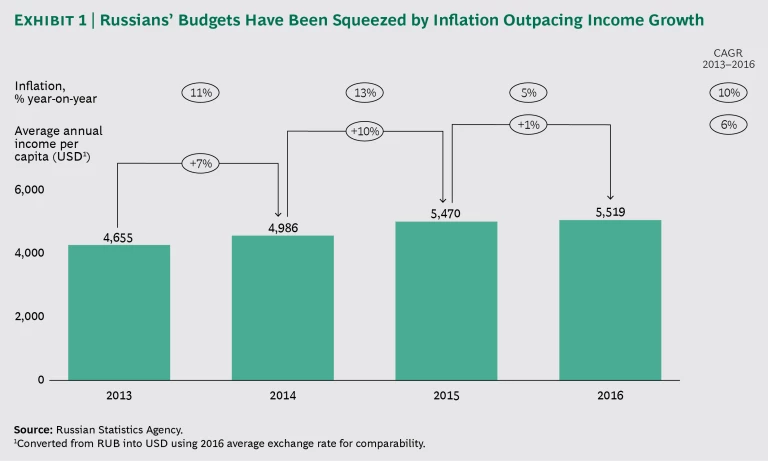

Lower global oil prices and Western sanctions following the Ukrainian political crisis have kept Russia from returning to its previous strong economic growth. Indeed, from 2014 through 2016, the economy contracted by an average of 2% per year, and the population living below the poverty line rose by 23%, to around 20 million. The ruble, meanwhile, devalued twice since 2014 against major currencies, making foreign goods and services more expensive. Consequently, inflation rose nearly twice as fast as incomes from 2013 through 2016, eroding household purchasing power. (See Exhibit 1). That means families must pay rising prices not only for imported luxuries such as cars, but also for daily necessities such as medicines and food.

Russia’s economy is now growing again, albeit at a slower pace than before 2014. Unemployment is low. The country also remains an important market for global companies. Russia consumed $700 billion in goods and services in 2016, and it remains a heavy importer of finished goods, spending around $40 billion in goods from China and around $20 billion in goods from Germany in 2016.

Russia consumed $700 billion in goods and services in 2016, and it remains a heavy importer of finished goods.

Moreover, Russia’s urban areas—where 74% of the population of 147 million resides—comprise rich opportunities for outside companies. In fact, around one-quarter of Russians live in cities of 1 million or more. Moscow, with 12.4 million inhabitants, is among the richest, with a per-capita income of around $12,000—nearly twice as high as the average for other Russian cities and nearly four times higher than in rural areas.

Our survey finds that, overall, Russian consumers are accepting that the economy is settling into a new reality of slow growth. While consumers are less optimistic about the future than they were in 2013, they also worry a little less. And while the 55% of respondents who say that they are optimistic about the future represents a 15 percentage-point drop from 2013, optimism is around the same level as in Australia, Canada, Germany, and the US—and markedly higher than in France, Japan, the UK, and Spain. The 72% who responded that they worry about the future is an improvement from 77% in 2013. Concern is highest among females, people living in households that have monthly incomes of $700 or less, and residents of large cities.

Not surprisingly, the sense of overall economic insecurity has risen. Of the respondents, 29% disagree with the statement, “I feel safe about my current job,” compared with 20% in 2013. Forty percent disagree that they feel safe about their financial situation—about the same level as before, but those strongly disagreeing rose sharply.

How Russian Consumers Set Priorities

When we asked Russian consumers what they value most, the overwhelming majority cited “family and home” (83%) and “health” (78%). These values rank well ahead of their responses on “freedom,” “prosperity,” and “comfort.” The order is roughly similar for women and men, as it is for most age groups. The spending priorities Russian consumers cite reflect the importance of these values. Our research finds that while consumers have generally become more conservative shoppers over the past few years, they are also willing to spend more—and absorb rising prices—on goods and services that enhance the quality of life of their families.

In response to the new economic reality, however, Russian consumers generally have become more rational about their purchases. In 2013, 60% of respondents agreed with the statement “I am happy because I can buy new things” and 42% with the statement “The more I buy the happier I am.” Those in agreement drop to 46% and 28%, respectively, in 2017. Still, respondents saying that shopping “makes me feel happy” actually rose, from 32% in 2013 to 41% in 2017.

Moreover, many Russians—especially those with low incomes—have tightened their purses. Thirty-six percent report that they plan to cut spending on “nonessential” goods in the year ahead, compared with 33% who gave that response in 2013. Forty-two percent of respondents with monthly household incomes of less than $350 say they are cutting spending, as do 33% of people whose income ranges from $350 to $700, which in Russia is regarded as the upper middle class. By contrast, only 20% of consumers with monthly incomes of more than $1,700—who are considered affluent—are cutting back. Thirty-eight percent say they prefer to save rather than spend—a big reversal in sentiment since 2013—and 48% plan to postpone large purchases, compared with 30% who plan to proceed with such purchases.

Consumers have become far more price-conscious over the past four years and are more actively chasing bargains. Fifty-seven percent plan to buy more promotional items, for example, compared with only 40% in 2013; 46% say they shop more frequently at discount stores or outlet malls, versus 33% before. The share of Russian consumers reporting that they frequently check prices online before a purchase rose from 40% to 47%.

Except for people with relatively high incomes, Russian consumers have also become more willing to forgo convenience and service when shopping. Among consumers with household incomes of $1,000 or less, more than 40% indicate they are unwilling to pay more to shop at a store that is conveniently located, compared with around 30% who agree. The response is similar for consumers asked if they would pay more in a store with better service.

Where Russians do spend, however, they still expect quality—regardless of where they shop or which brand they choose. Forty-six percent of respondents plan to shift their purchases to higher-quality goods and services—more than three times as many as those who say they have no such plans. (The remainder was neutral.) But only 17% indicate that they plan to shift more of their spending to premium stores, while 49% disagree. The gap is even wider when consumers were asked if they plan to switch to premium brands, with 14% agreeing and 55% disagreeing.

Consumers still expect quality—regardless of where they shop or which brand they choose.

Where Russians Are Spending More—and Cutting Back

Russian consumers are becoming noticeably more mindful about what they buy. They are focusing more on product categories that clearly define their living standards while cutting back on purchases they regard as wasteful. They are less willing to spend extra for prestigious brands and are more interested in value for money. Where they can afford it, however, Russian consumers generally plan to spend more—either because they are willing to absorb higher prices or because they wish to increase spending on higher-value goods and services—in categories that are important to them.

In our survey, we asked consumers about specific product categories where they increased spending over the past two to three years, and where they plan to spend more in the year ahead. We also asked about categories where they reduced spending and plan to continue doing so. In addition, we asked them to choose categories on which they would like to spend more but are cutting back out of necessity.

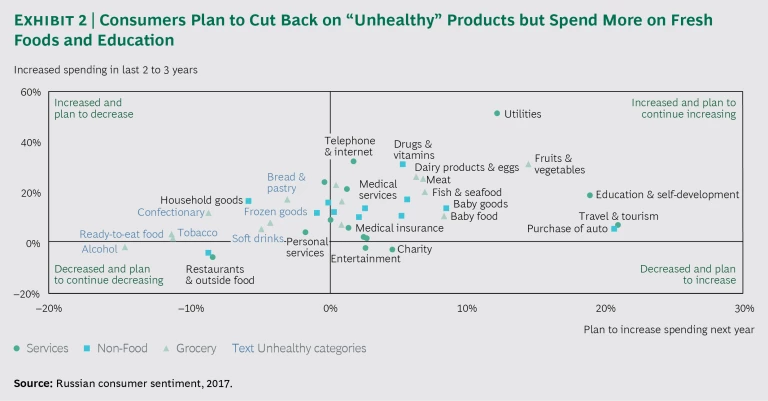

Categories consumers cite most often as priorities for increased spending relate to healthful eating, well-being, and personal enrichment. For example, respondents place a high emphasis on fresh foods. Twenty-six percent intend to spend more in the coming year on fruits and vegetables, while 21% cite fish and seafood, 20% meat, and 18% dairy products and eggs. Roughly twice as many respondents plan to spend more on these categories than those who say they intend to spend less. These responses suggest that consumers are willing to pay higher prices rather than sacrifice fresh foods. When we probed a bit deeper, around 80% of respondents told us that these categories are either too important to skimp on or that they would spend more on them if they didn’t have to save money.

At the same time, consumers are cutting back on groceries that they perceive as less healthy. In some categories, this represents a recent shift. Many consumers say that over the past two to three years, they decreased their purchases of tobacco products, frozen foods, ready-to-eat foods, and confections. (See Exhibit 2.) Those categories now rank as top targets for decreased spending. Consumers say they also plan to continue spending less on alcohol.

Among nonfood categories, 22% say they plan to spend more on pharmaceutical drugs and vitamins—again an indication that many consumers are willing to pay higher prices rather than sacrifice their health. The same percentage also say they intend to spend more on clothing and shoes and home furnishings. Fifty-six percent say they want to spend more on clothing and shoes but must cut back in order to save; 49% say they are cutting back on furnishings out of necessity; while 46% are spending less money on home appliances and 45% spend less on electronics. These responses suggest that Russian consumers have been postponing purchases of many items and are ready to spend when they feel they can better afford them. This tells us that companies in these categories that maintain a strong presence in the market could eventually capitalize on significant pent-up demand.

In terms of services, the top category for higher spending is tourism, which 31% of Russian respondents cite—three times as many as those who say they are cutting back; 47% say they want to spend more on travel but can’t because they have to save. Twenty-two percent plan to spend more on education and self-development. Asked where they plan to tighten their budgets, the most frequently cited categories were those perceived as wasteful, such outside dining and personal services.

When we asked Russian consumers about their attitudes toward brands, 61% of respondents report that they prefer buying goods and services with familiar brands. Generally, however, Russians’ love affair with brands has eroded. In 2013, 34% of respondents agreed with the statement, “Brands reflect what I am and my values.” That drops to 24% in the 2017 survey. Factors such as whether or not friends and family approve of their brand choices or whether products come from companies that are environmentally conscious also have become less important since 2013. These findings indicate that declining real incomes have made Russian consumers more cost-conscious—suggesting a great opportunity for mass-market brands and generics that offer value for money. Recent trends indicate that more Russian consumers are less willing to spend on the newest name-brand smartphones, for example, and instead are choosing lower-priced Chinese models.

Declining incomes have made Russian consumers more cost-conscious—suggesting a great opportunity for mass-market brands and generics.

Spending Potential in Three Crucial Industries

To better understand how Russian consumers plan to buy what they need and want, given their financial circumstances, we explored three sectors in-depth: health care, travel and tourism, and automobiles.

Health Care. Our research indicates a huge unmet demand for high-quality medical services in Russia—for providers that can deliver health care efficiently and affordably. Aside from their families and homes, consumers most often cite health as their top priority. Forty-two percent of respondents say they suffer chronic conditions such as cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and respiratory diseases.

As Russia’s population continues to age—and diagnostic methods improve—demand for medical services will grow. Yet most Russian consumers perceive the nation’s medical system as inadequate. And because many of the most advanced drugs and medical devices are imported with devalued rubles, treatments are expensive. Despite the current difficult economic environment, 41% of respondents increased their spending on medicine over the past two or three years—primarily because of higher prices— and 30% spent more on medical services. Significant numbers report they will likely spend more on medical care in the coming year as well.

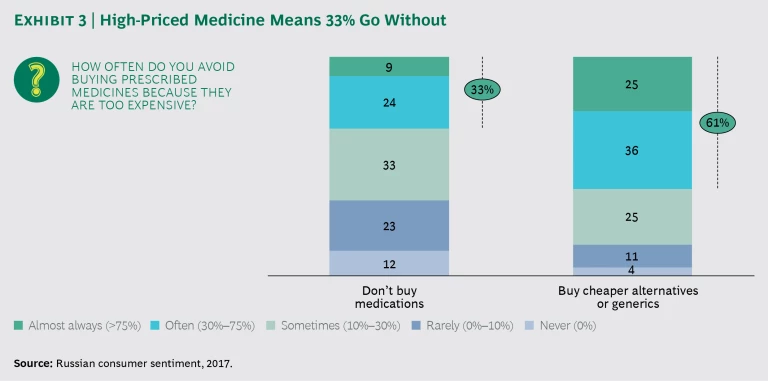

But soaring costs are forcing consumers to make difficult choices. Sixty-six percent of respondents say they try to save money on medications; 78% say the same about medical services, and 87% about health insurance. Thirty-three percent report they sometimes don’t buy prescribed medicines at all because they unaffordable. And 74% of those with chronic diseases say they would consume more medicine if it were subsidized by the government—which suggests they take less than the recommended dosages. This is primarily because drug prices are highly influenced by currency fluctuations, forcing patients to pay more for medications or do without.

These findings indicate a huge demand for affordable, high-quality medical services in Russia that’s not being fully met by public programs. Although diseases that come with aging are on the rise in Russia, the government-subsidized health insurance market is projected to remain at current levels.

The high prices of imported branded drugs present big opportunities for providers of inexpensive generics. Sixty-one percent of respondents say they “often” or “almost always” buy cheaper generics, and 94% of those with chronic diseases say they buy generics. (See Exhibit 3.) One pharmaceutical company capturing the opportunity in that market is Slovenia-based KRKA. The company has emerged as Russia’s eighth-largest supplier of retail medicines, with a business model focusing on its own brands of generic cardiovascular and alimentary drugs, affordable pricing, broad coverage, and sound management of its products’ life cycle. In fact, the company’s strong profits in Russia finance its aggressive investments to expand its coverage of doctors and get its products on the shelves of pharmacy chains. And every year, the company introduces at least one new product in Russia. From 2011 through 2015, KRKA averaged 15% annual sales growth—well above the industry average.

Our research confirms that there is a big need for better medical services in Russia. Fifty-eight percent of our respondents say they pick health care providers based on the doctors. But high-quality medical professionals are in short supply, especially outside of big cities; 34% of respondents say their primary care doctors don’t meet their expectations. Russian respondents cite high levels of discontent with the quality of both public and private inpatient and home care.

All of these findings indicate that Russia is an attractive environment for foreign providers. Indeed, private investment in Russia’s health sector reached an all-time high of $460 million in 2016. Russian clinics are already expanding their networks into new regions. Among the foreign investors entering Russia are the Italian medical holding company GVM, whose investments include a clinic being built in Moscow; and Acibadem Sistina, a leading Macedonian clinic that in 2016 announced it would invest in a multidisciplinary hospital in the southern city Rostov-on-Don.

One of the most ambitious health care projects involving foreign investment is the Moscow International Medical Cluster, a government-backed initiative that will include up to 15 state-of-the-art facilities that aim to improve access to global treatment methods. A 2015 federal law lowered administrative barriers to foreign participants in the health cluster and simplified systems for regulating them. That means leading international health care players operating inside the cluster can deploy treatment protocols, technologies, and medicines without obtaining government authorizations, while restrictions on foreign specialists will be lifted. The cluster’s first foreign partner, Israel’s Hadassah Medical Center, will operate a clinical diagnostic center and an oncology therapy center.

The shortage of medical professionals also makes Russia an attractive market for remote medical services. There’s clearly room to grow in this area: only 8% of respondents say they currently use telemedicine, mainly because they distrust its quality. Another constraint is that 45% of Russian patients say they don’t use the internet for health care at all. But new government regulations should begin to boost remote medical services. The Russian company Doc+, for example, offers online consultations and home visits that can be booked online. Russian telecommunication, technology, and financial services companies have also announced telemedicine projects. The Renaissance Insurance Group, for example, introduced a remote medical advisory service in cooperation with the Doctor Ryadom clinic network; and Sberbank recently formed a partnership with the Mother & Child chain of medical centers to help develop DocDoc, a federal health care marketplace it purchased in 2017 as part of its goal to build a national health care ecosystem. As Russian consumers become more technologically sophisticated, more providers are exploring ways to deploy new medical devices to bring patient care to homes and reduce the role of hospitals.

As consumers become more technologically sophisticated, more health care providers are exploring ways to reduce the role of hospitals.

Travel and Tourism. Regardless of their financial circumstances, Russians value the opportunity to travel. Measured in rubles, Russian tourism spending has remained fairly stable since 2013, as has airline passenger traffic. And despite the sluggish economy, 62% percent of respondents say travel and tourism are important enough that they don’t intend to cut their spending and, in fact, would spend more if they could afford to. A full 51% of consumers with monthly household incomes of $350 or less and nearly 80% of households with incomes from $700 to $1,700 indicate that they won’t cut back or that they want to spend more.

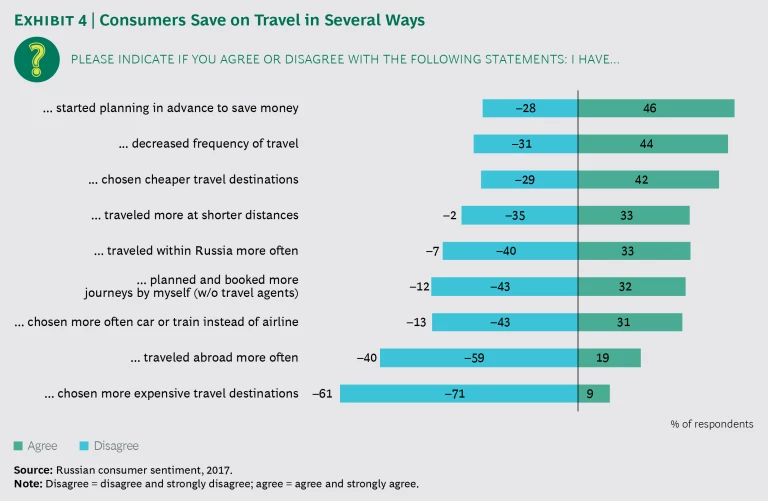

Despite Russians’ desire to travel, the ruble’s declining purchasing power has kept them close to home. A full 33% of respondents say they are traveling within Russia more often, with 31% traveling more often by car or train rather than airplane. That’s largely because prices for domestic air tickets, which are sold in rubles, have remained stable, while prices for international travel have risen sharply. The average price for a tour of top international destinations for Russians, which includes Turkey, Egypt, Greece, and Spain, leapt 16% in 2016, for example. As a result, 26% of consumers say they were forced to spend more on travel over the past two or three years.

Russians are also learning to stretch their travel budgets by choosing cheaper travel destinations (42%), traveling less frequently (44%), and planning trips in advance to save money (46%). (See Exhibit 4.) Of those who plan to spend money on a vacation, 66% of respondents say they make the decision at least one month in advance and 33% at least three months beforehand. Slightly more than half book accommodations and air travel at roughly the same time, at least one month in advance, whereas 19% and 18%, respectively, book three months or more in advance.

All of this indicates that operators and agencies targeting Russia should be more price-sensitive, offering more affordable packages rather than the luxury travel Russians once preferred. They should also consider last-minute flash sales to destinations that have become expensive but remain popular with Russians—such as France—when flights and hotels are underbooked. These findings also suggest opportunities for travel operators and agencies offering tourist destinations less affected by the ruble devaluation, including Vietnam, China, and Turkey. Shorter and more flexible packages—such as ten-day rather than two-week vacations—are other options.

Another sign that Russian travelers have become more price-conscious is that 36% have a positive view of an emerging trend in Russia: air tickets that cover only the cost of travel itself, with the option to pay extra for such services as meals, luggage storage, and seat selection. Only 26% express a negative view of such pricing.

While e-commerce remains underdeveloped in Russia, our research also finds that consumers are going online more to book their travel. Forty-five percent of respondents who say they travel agreed with the statement, “I have started to more actively use websites and apps for planning and booking travel.” Consumers also said they commonly use websites and phone apps of airlines, hotels, and car rental agencies to book personal travel. While airline offices and travel agencies remain popular, roughly the same percentage of travelers say they now book through online aggregators.

This indicates that travel operators should consider developing an active and robust online presence in Russia. In addition to international social media such as Facebook and Instagram, providers can also leverage domestic platforms, such as Vkontakte and Yandex. One airline with a strong online strategy is KLM, which publishes interesting offers, articles on destinations, and contests tailored to Russian travelers.

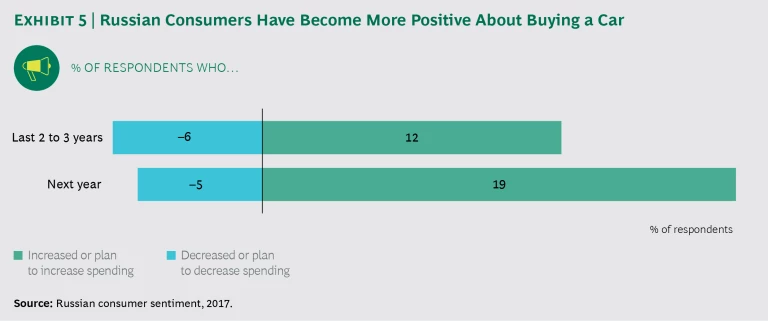

Automotive. After a sharp contraction from 2012 through 2016, when unit sales plunged by more than half, Russia’s passenger car market is showing signs of recovery. Our research also suggests that consumers are in a better mood to buy. Nineteen percent of the consumers we surveyed, particularly those who are middle-aged and have high incomes, report plans to increase their spending on automobiles in the year ahead, a big improvement from the past two to three years. (See Exhibit 5.)

Our research also finds that Russian consumers hold foreign brands in high regard—with Toyota ranking at the top in brand loyalty—while having relatively low loyalty to the domestic brand Lada. It also finds that 55% of car buyers use the internet for comparing prices, while 47% search for product information online. This suggests that it is critical for OEMs to have local websites and a visible local presence.

Reaching Russian automotive consumers remains a challenge. Credit for car purchases is expensive, even though interest rates have decreased from 16% to 8% over past three years, and the geographic reach of service and dealer networks is still limited. The success of Asian OEMs, however, implies rich opportunities for automakers that offer models that fit the needs and budgets of Russian consumers—and that are willing to invest in a strong on-the-ground presence despite the economic headwinds.

Several Asian automakers have significantly boosted their market share by targeting the so-called “new Russian middle class,” the nation’s most dynamic purchasing segment. Such individuals wish to buy a high-quality car, but they cannot afford premium models. The Asian OEMs offer popular models priced at around $10,500 and continued to invest in local production through difficult economic times. They also procure from domestic suppliers.

As a result, the Asian automakers not only have been able to comply with Russian local-content rules imposed in 2015; they also have kept costs low when the ruble began to plunge, making imported cars and components more expensive. Now, several are building large dealer networks across Russia.

Several Asian automakers have boosted their market share by offering popular models priced at around $10,500.

Seizing Advantage During Russia’s Economic Reset

As Russian consumers reset their expectations in light of the new economic reality, so must companies that hope to gain competitive advantage in this still-important market. Many multinationals that have approached Russia as just another emerging market—and believe the same mix of products and go-to-market strategies will earn high, predictable growth—must reassess their approach. After all, Russia has built up considerable demand in a range of product categories, after years of restrained household spending. Big opportunities also exist to reach vast pools of consumers whose needs currently are not met by domestic industries.

To win, companies must bring the right value proposition. To the degree that their brand concepts allow, companies should consider adding more-affordable options to their product portfolios, for example, or introducing new brands aimed at the budget market. They should also explore innovative business models for bringing products to the Russian market.

Companies already operating in Russia since the boom years should reassess their on-the-ground operations and talent. They will need to ensure that they have the right capabilities to win in this increasingly complex market. And if companies are considering cutting back their Russian operations until they see clearer evidence of a turnaround—they should think twice. They should position for the future and invest in the people, logistical and service networks, and online presence needed to win market share and to reach consumers beyond the biggest Russian cities.

The winners in Russia over the long term will be companies that use the current economic reset to seize competitive advantage.