This is an excerpt from Striking a Balance Between Well-Being and Growth: The 2018 Sustainable Economic Development Assessment .

The past decade has been a turbulent one, marked by a global financial crisis and recession in many parts of the world. In the wake of those events, it is worth assessing the evolution of well-being globally.

To do this, we used BCG’s Sustainable Economic Development Assessment (SEDA).

The 2018 Sustainable Economic Development Assessment

The 2018 Sustainable Economic Development Assessment

- Striking a Balance Between Well-Being and Growth

- Well-Being Trends over the Past Decade

SEDA , launched in 2012, is a diagnostic tool designed to provide insight into the relative well-being of a country’s citizens and how effectively a country converts wealth, as measured by income levels, into well-being. (See “Defining and Measuring Well-Being.”)

Defining and Measuring Well-Being

Defining and Measuring Well-Being

SEDA is primarily an objective measure (combining data on outcomes, such as in health and education, with quasi-objective data, such as on the quality of infrastructure or governance, derived from surveys and expert assessments). It does not include purely subjective perception measures. Other metrics based on subjective measures—such as the ones used in the World Happiness Report—offer valuable complementary, but separate, insights. In fact, we have found a strong overall positive correlation between the scores from the World Happiness Report and SEDA scores.

SEDA is also a relative measure; it assesses how a country performs relative to either the entire universe of countries in the data set or to individual peers or groups. SEDA offers a current snapshot as well as a measure of progress over time, and it complements purely economic indicators such as GDP. (For details on the SEDA methodology and the 2018 analysis, see the Appendix at the end of the full report.)

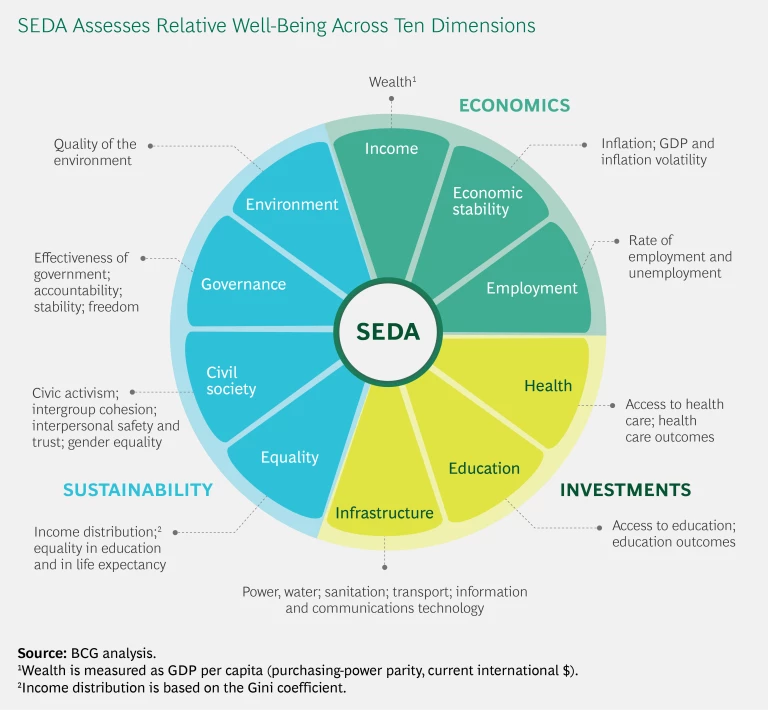

SEDA defines well-being on the basis of ten dimensions grouped into three categories. (See the exhibit.)

- Economics includes the dimensions of income, economic stability, and employment.

- Investments includes the dimensions of education, health, and infrastructure, which reflect the outcomes of policies and programs that account for the bulk of any government’s nondefense expenditures.

- Sustainability comprises the environment dimension and three that contribute to social inclusion: equality, civil society, and governance.

- SEDA Score. We aggregate the scores for the ten SEDA dimensions to provide an overall score for each country. This score can be used to compare a country with any other country or group of countries. In general, wealthier countries tend to have higher scores than less wealthy countries. SEDA’s ten dimensions also provide a framework for reviewing priorities for remedial action, since a country’s performance relative to the rest of the world or to a group of peers can highlight critical strengths and weaknesses. Armed with such insights, governments can begin to set strategies for addressing the most pressing issues.

- Change in SEDA Score. This year, we have changed the way we measure countries’ progress in well-being. With ten years of data of comparable SEDA scores, we can track the change in SEDA score over that period. We can also track changes in each dimension of the SEDA score.

- Wealth-to-Well-Being Coefficient. On the basis of their SEDA scores, we can examine how effectively countries are able to convert their wealth (as reflected in income per capita) into well-being. We do this using a measure called the wealth-to-well-being coefficient. This coefficient compares a country’s SEDA score with the score that would be expected given the country’s GNI (gross national income) per capita. The coefficient thus provides a relative indicator of how well a country has converted its wealth into the well-being of its population. Countries with a coefficient of 1.0 are generating well-being in line with what would be expected given their income levels. Countries that have a coefficient greater than 1.0 deliver higher levels of well-being than would be expected given their GNI levels, while those below 1.0 deliver lower levels of well-being than would be expected.

Our 2018 analysis, which included 152 countries and used data from 2007 through 2016, allowed us to look back over the past decade to examine some important issues.

We analyzed how well-being in absolute terms fared during that period and which countries made the most and the least progress. The following interactive guide to SEDA presents the results of our 2018 analysis.

We also dug into the relationship between well-being and growth, finding that countries that focus on enhancing well-being not only raise the standard of living of their citizens but also set their country up for stronger and more resilient economic growth. (See

Striking a Balance Between Well-Being and Growth

.)

Positive Signs for Global Well-Being

To understand how well-being has changed on an absolute basis, we can look at the metrics that constitute our SEDA scores. Those scores are based on normalized indicators on a scale of 0 to 100 and therefore reflect how countries have performed relative to one another. To understand the trends in absolute well-being levels, we can instead examine changes in the 40 indicators (without any normalization) that we use to derive the overall SEDA scores.

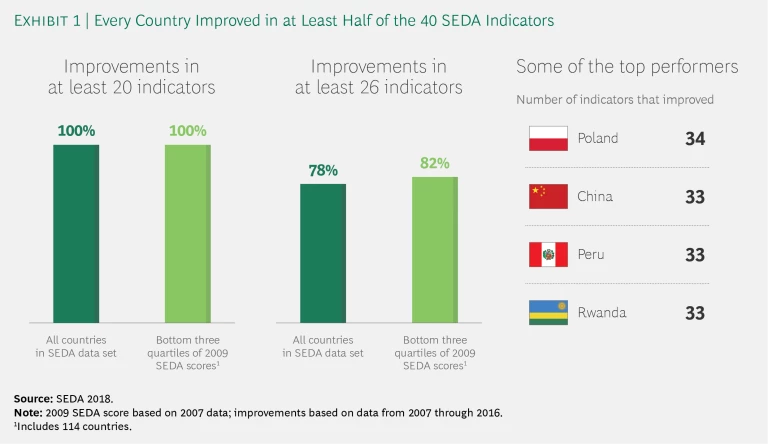

Looking at the indicator performance for all countries in our SEDA database, we see reason for optimism. We found that in every country at least half of SEDA’s 40 indicators improved in absolute terms over the ten-year period we analyzed, and in 78% of the 152 countries at least 26 of the indicators (65% of the total) improved. (For more detail on indicator performance, see the Appendix at the end of the full report .)

Because countries that start with high well-being levels have less room for improvement, it is particularly useful to look beyond those countries as we examine trends. If we consider only the 114 countries in the bottom three quartiles of 2009 SEDA scores, we find that 82% of them had gains from 2007 to 2016 in at least 26 indicators. Among those that had the biggest gains were Poland, with improvement in 34 indicators, and China, Peru, and Rwanda, with improvement in 33. (See Exhibit 1.)

When we look at the entire set of 152 countries, we see significant gains from 2007 through 2016 in key health outcomes (notably, life expectancy and under-five mortality), in education (notably, school enrollment and years of education), in equality, and in infrastructure. Within infrastructure, the big gains in digital infrastructure are very encouraging—particularly for countries that have relatively low levels of well-being. (See “The Digital Imperative.”)

The Digital Imperative

The Digital Imperative

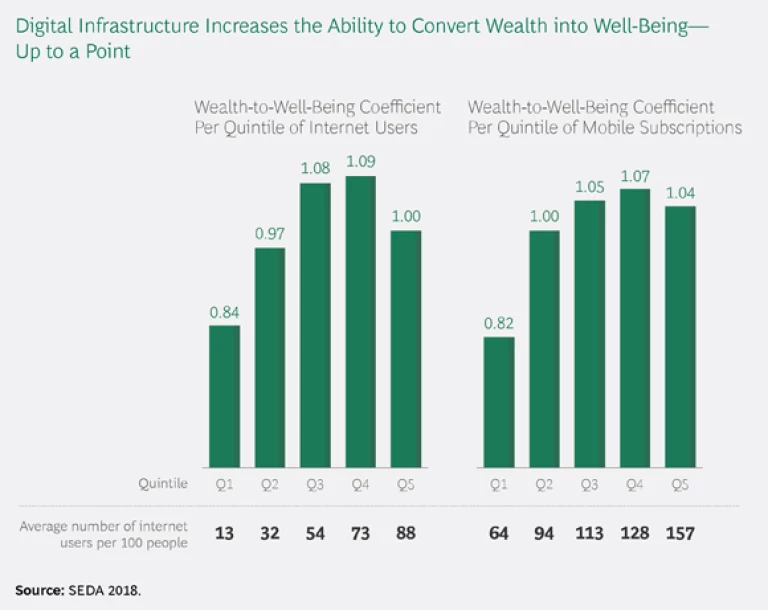

We found that a country’s ability to convert wealth into well-being is clearly associated with its level of digital technology adoption. We saw this, for instance, in analyzing the relationship between SEDA’s wealth-to-well-being coefficient and both internet and mobile usage. (See the exhibit.) The relationship is positive and significant at levels of low and middle usage. However, it appears to become negative at higher usage levels: additional investment in digital infrastructure does not seem to boost well-being. We saw a similar relationship between the wealth-to-well-being coefficient and other digital metrics, including the World Economic Forum’s Networked Readiness Index.

The positive link makes sense given the impact digital infrastructure can have on other SEDA dimensions. Robust digital infrastructure, for example, has major implications for employment as the rules surrounding global competition evolve. (See “ Why Countries Need New Job Creation Strategies,” BCG article, May 2018.) It improves education by expanding the access of students to new material or instruction, and it strengthens governance by involving citizens more directly in decision making and reducing inequality in access to information. All this makes it critical that governments—in particular in developing countries, where digital infrastructure availability and usage are lower—put the widespread adoption of digital technology at the top of the policy agenda.

We also see some improvement in gender equality in most countries, which has a significant effect on overall well-being. (See “Why Everyone Benefits from Gender Equality.”) In particular, gender diversity has major implications for a country’s economy, boosting productivity and innovation by unlocking the full potential of the nation’s talent pool.

Why Everyone Benefits from Gender Equality

Why Everyone Benefits from Gender Equality

No doubt, there are signs of progress when it comes to gender equality. Some 83% of the countries in our data set improved their gender equality ratings (an indicator within our civil society dimension) from 2007 through 2016. The improvements were generally modest, but they were statistically significant and observed across locations and country development levels. We see evidence of this trend in more granular statistics as well, including women’s enrollment in education and labor force participation.

These gains have meaningful ripple effects. That’s because there is a significant positive relationship between a country’s gender equality and how well it converts wealth into well-being. (See the exhibit.) This finding is consistent with research on the socioeconomic benefits of reducing gender inequality. Further, it indicates that higher gender equality has an impact on many aspects of well-being.

Certainly, there is much more work to be done. For example, legal rights, access to education, and labor practices still have much room for improvement in many parts of the world. Nevertheless, if countries take aim at the gender gap in those areas, they may also drive meaningful improvements in both economic growth and well-being.

In the area of governance, the picture is much more mixed. The only governance indicator that improved in most countries was the protection of property rights; the remaining indicators improved only in a minority of countries. (The three other governance indicators are political stability and absence of violence and terrorism, corruption and rule of law, and voice and accountability.) The picture on the environment is also concerning: air quality and carbon emissions worsened in most countries, with generalized improvement only in the generation of electricity from renewable sources.

Overview of 2018 SEDA Results

The results from our 2018 analysis reveal that while many of the Western European countries that boast the highest scores also did so in previous analyses, the breadth and depth of the financial crisis took a toll on several of them (especially in the employment dimension). At the same time, many high-growth countries were able to improve their well-being scores despite the powerful global economic headwinds.

Wealthy countries with strong institutions lead on SEDA scores. European countries account for 71% of the countries in the top quartile of 2018 SEDA scores. Northern European countries top the list—as they have since we launched SEDA—owing in part to high income levels and a strong commitment to social progress and governance. This year, Norway and Switzerland are SEDA’s top-ranked countries, with Iceland, Luxembourg, and Denmark rounding out the top five.

Singapore is the only non-European nation in SEDA 2018’s top ten. Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, the UK, and the US are the only G20 countries in the SEDA 2018 top 20.

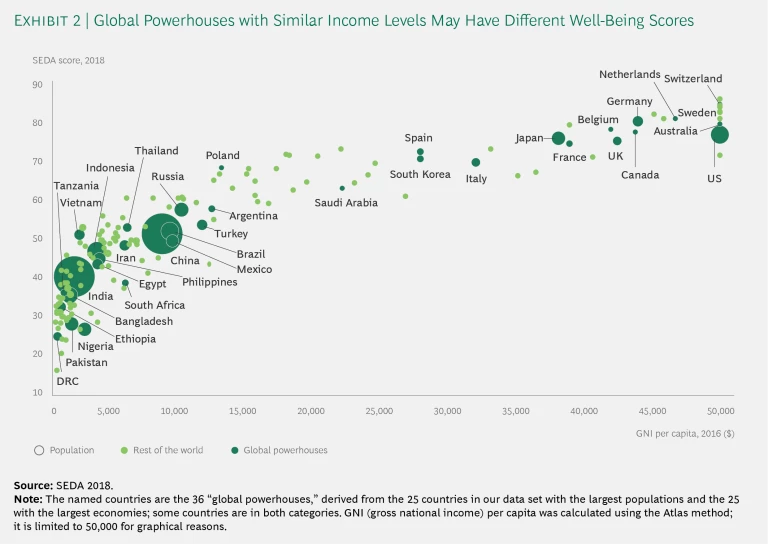

However, as noted earlier, high income is not a guarantee of high levels of well-being. Consider the 36 global powerhouse countries outlined above.

High income is not a guarantee of high levels of well-being.

When we look at these countries according to SEDA scores and per-capita incomes, we see that countries with similar incomes can have very different levels of well-being. (See Exhibit 2.) The US and Australia, for example, both have GNI (gross national income) per capita in the mid-$50,000 range—but the US’s SEDA score is 76, while Australia’s is 79. Meanwhile, Germany’s GNI per capita is more than 10% below that of both countries, but its SEDA score is on par with Australia’s and better than that of the US.

Some countries saw big changes in SEDA scores over ten years. Well-being levels reflect the cumulative effects of policy decisions, institutions, and investments. As a result, we tend not to see big changes in scores from one year to the next. Movement is more visible, however, when we look at ten years of SEDA scores, from 2009 through 2018.

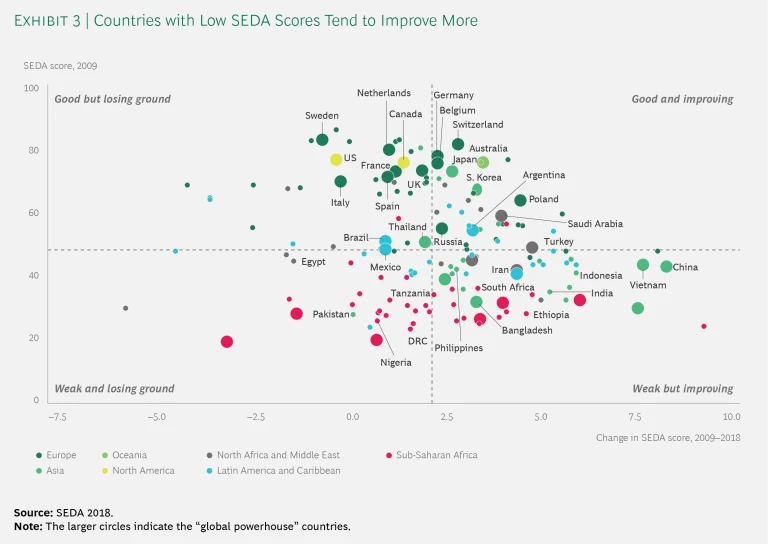

Overall, we see signs of convergence over that period: countries with high SEDA scores tend to show relatively low progress, while those with low SEDA scores tend to show more progress. (See Exhibit 3.) But there are many exceptions. This underscores that there is no natural law driving convergence, a reality reflected in the fact that we see many countries in every quadrant of Exhibit 3. A country’s policy decisions and spending priorities are the primary determinants of progress.

Each quadrant tells a different story about performance in well-being over the past decade. Western countries heavily affected by the financial crisis make up most of the good but losing ground quadrant. Asia includes several weak but improving examples. Performance varied significantly among countries in sub-Saharan Africa, many of which fall in either the weak but improving or the weak and losing ground quadrant.

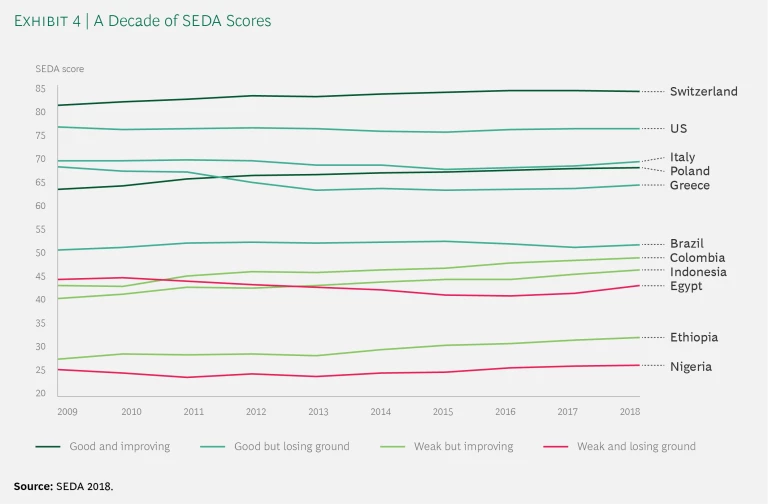

Exhibit 4 zooms in on some country trajectories. Take Switzerland and the US, both of which have high levels of well-being. While Switzerland’s score has continued to improve, however, the US’s has been declining slightly, widening the gap between the two countries. The scores of Italy and Greece show the prolonged effect of the economic crisis, with both countries losing ground over the past ten years. Poland, in contrast, started at a lower level but thanks to steady improvements has nearly caught up to Italy and has surpassed Greece. Colombia and Indonesia, meanwhile, started at similar levels and have both improved, the former at a slightly faster rate. Both have overtaken Egypt and are now approaching Brazil, which improved initially and stagnated more recently. Finally, Ethiopia and Nigeria started the decade at roughly the same level of well-being, but the former has made solid strides while the latter has delivered little improvement in its SEDA score.

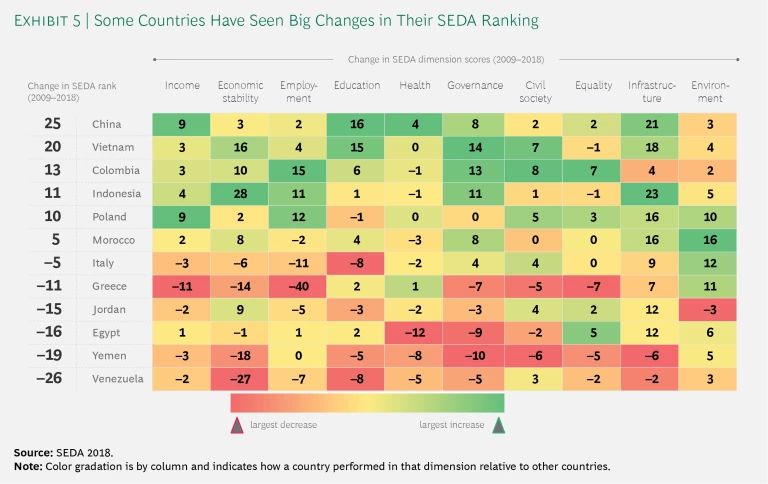

It is also useful to look at how SEDA rankings (on a scale of 1, the highest, to 152, the lowest) have changed over the past ten years and which dimensions have contributed to those changes.

Vietnam has improved across the board, with a particularly strong showing in economic stability, education, governance, and infrastructure. As a result, the country has jumped 20 spots, moving from the third to the second quartile.

Other countries, such as China, Colombia, and Morocco, also made meaningful gains in our ranking as a result of strong improvement in a variety of areas. For China, which jumped 25 spots, progress stemmed in large part from improvements in education and infrastructure. Colombia, which jumped 13 spots, improved most in employment, governance, and civil society, while Morocco’s overall improvement stemmed largely from progress in economic stability, governance, infrastructure, and environment, leading to a gain of five spots.

Certainly, there were big movers on the downside as well. Yemen dropped 19 places in our ranking, hardly surprising given the impact of the country’s civil war. Greece also slipped considerably. The country had the worst performance in employment: by 2016, that dimension had barely recovered from the crisis. Egypt and Jordan experienced major setbacks in governance. Meanwhile, Venezuela dropped the most in the ranking (26 places) because of poor performance in all dimensions, in particular in economic stability, education, health, and governance.

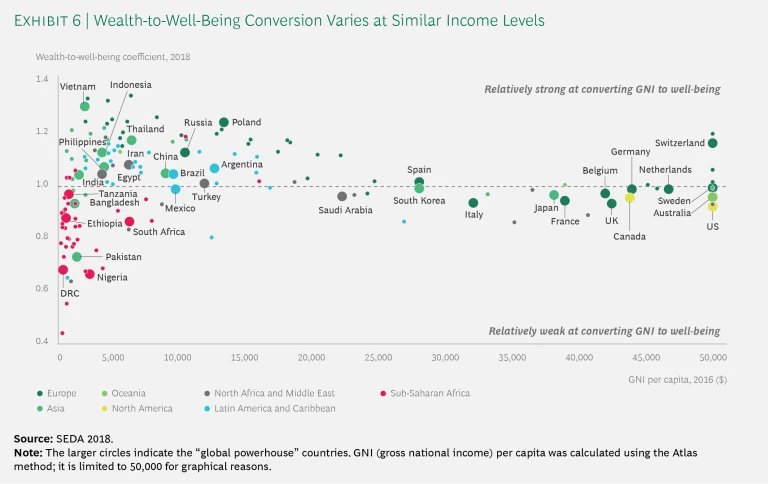

Performance in converting wealth into well-being varies. As we have found in previous years, the ability to convert wealth into well-being varies even among countries with similar income levels. (See Exhibit 6.) Both the US and Sweden, for example, have per-capita income in the mid-$50,000 range, but the US has a coefficient of .91 while Sweden’s is .98. Poland and Argentina also have similar per-capita income levels (roughly $12,000), but Poland’s coefficient is 1.22 while Argentina’s is 1.05. It is worth noting that small differences in the coefficient can translate into large differences in the absolute level of well-being. As discussed, those variations, in turn, can have a major impact on long-term economic growth.

Three patterns stand out in the 2018 coefficient results. First, many of the countries with the highest coefficients are in Eastern and Central Europe. Second, oil-rich countries tend to perform worse than average in converting wealth into well-being. The oil-exporting countries in the Gulf, for instance, all have coefficients below the global average—although Saudi Arabia’s has been close to the average over the past decade, and Qatar’s has gradually improved to a similar level. Third, the bulk of countries in sub-Saharan Africa are still lagging in this area, with most posting coefficient scores below 1—meaning that their ability to convert wealth into well-being is below the global average for countries at their income level. While there are some notable exceptions, including Ghana and Rwanda, the overall pattern is worrisome. Not only do countries in sub-Saharan Africa have limited resources to direct toward areas that bolster well-being, but they are also not effective at converting the wealth they do have.