This is a modal window.

With nationalism and populism on the rise in Europe, the region’s unique social-economic model has come under pressure. Jeroen Dijsselbloem, a former president of the Eurogroup and minister of finance of the Netherlands, met with BCG senior partner and managing director Alexander Roos to discuss strategies for safeguarding the model’s future. They discussed, among other topics, populism’s potential to spark greater unrest in Europe, the question of whether the balance between markets and government must be reconsidered, next steps in the integration of European banking, and risks to the global economy.

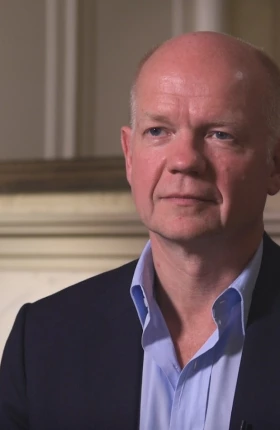

About Jeroen Dijsselbloem

About Jeroen Dijsselbloem

Former President, the Eurogroup; Former Minister of Finance, the Netherlands

An experienced economist and politician, Jeroen Dijsselbloem has dealt with a number of major economic situations in Europe, including the Cyprus bailout and the debt crisis in Greece, as well as proposals on the future of the European monetary union.

He served as president of the Eurogroup from January 21, 2013, through January 12, 2018, and as president of the Board of Governors of the European Stability Mechanism from February 11, 2013, until January 12, 2018.

He was the appointed minister of finance of the Netherlands from November 5, 2012, through October 26, 2017, and was a member of the House of Representatives from 2000 to 2002, 2002 to 2012, and briefly in 2017. From 1985 through 1991, he studied agricultural economics at Wageningen University and was elected to the municipal council of Wageningen, in which he served from 1994 through 1997.

In recent elections, we’ve seen hints of rising nationalism. Do you see this reflecting a critical signal on capitalism in Europe? Has capitalism failed?

I don’t think that we have capitalism in Europe in the purest sense. We have a social-economic model that is quite unusual in the world: a combination of a strong economy and a well-developed welfare state. There is some variance, of course, within Europe, but that’s the basis. I think it needs maintenance: the key to our social-welfare state and our social economy is fairness. And there are a lot of people worried about fairness, which has to do with who are actually paying the taxes and who are not, who are getting the opportunities, who are enjoying globalization and who are taking the costs there, and what’s the perspective for their children.

Reflecting on the current situation in Europe, what do you see as the biggest single risk, introducing unrest in Europe?

I would say the biggest risk that we are facing in Europe—but not just in Europe—is populism. Europe was undisputed for a long postwar period, during which people were very confident that Europe would contribute to prosperity and to security—peace. Their expectations stemmed from confidence that Europe was an asset to wealth and security. That confidence has been shocked—mainly by the financial crisis and the migration issue. Now that we’re moving out of the crisis, growth is quite strong in the Eurozone; unemployment is going down, but it’s still high in a number of countries. Debt is still high also in households. There are still repairs to be done, and that’s taking time.

With soaring inequalities in the system, do we need to rethink the balance between markets and government and between individual freedom and the larger system in order to protect the fairness you mentioned?

It certainly requires a very active government, a very well-organized and effective public sector. This is about a tax system that is fair, in which all of us, and the large multinational companies, pay their fair share. Apart from that, I would say that markets can play a much bigger role in stabilizing our economy. We have been expecting a lot from the national governments and their public budgets: to sort out the banks, sort out the economic crisis. But not all of us have had the fiscal space, the budgetary space, to make those funds available. Markets here and private capital need to play a strong role in new investments in Europe, investing in sustainability and investing in opportunities. And when the next crisis hits, private players will have to be able to carry their own losses to a much larger extent than in the last financial crisis.

Europe has to deal with quite a few economic demons these days, one of which is banking integration. What are your thoughts on the path forward for Europe?

The banks, we all know, are crucial in our economy. There are three things that we need to do. First, we need to become less bank dependent. In the US, 25% of the economy comes from bank finance, and the rest is from, for example, more private finance, corporate bonds, and private equity. We need that kind of capital market also in Europe to diversify the way we finance our economy.

Second, we need to continue cleaning up the banks where there are still problems: nonperforming loans, for example. There are a lot of legacy issues still, but I’m optimistic. I think that a lot of work has been done and is ongoing.

Third, we need to finish the banking union. I would say that three-quarters of it is done, but the last part is important for encouraging trust in markets and trust from deposit holders. Let’s finish it.

Looking at today’s global economy, what do you see as the biggest risks? Are we looking at environmental, societal, or purely financial issues?

Political issues are the biggest source of instability at the moment. In the postwar period, the US has been leading on foreign policy, on defense, on trade. And up through the previous administration, it was also leading in the field of climate change. We are in a difficult situation now, and Europe needs to lead more. I think that’s the only answer that’s possible for dealing with this divergence of ideas and approaches. We need to continue to prepare for climate change and to stop it in time. Europe has no other choice. We need to do more on defense. The Americans have a true point there. We need to take the lead in topics such as free trade, which is in Europe’s interest, and on foreign-policy issues, in which we diverge with the approach that the American government is taking.

Thank you very much for speaking with us. It was a true pleasure.

Thank you very much.