In media, it is especially good to be the king. A handful of digital giants are so dominant in their markets that their positions appear essentially untouchable. These unassailable castles are value-creation machines, but they’re also something else: an aspiration for other companies. In media segments such as publishing and broadcast TV, many traditional players are looking—and even struggling—to transform themselves for a digital world. But some companies are succeeding in making the transition. Often these companies are doing so by taking a page from the digital giants’ playbook: creating a strong and defensible position by building a moat, so to speak, around a new or reengineered business model. These companies are taking a number of approaches to fortify their position: acquisitions, partnerships, and the development of new capabilities. It’s an effort that other media companies can undertake, too.

Digital Media Leads the Field

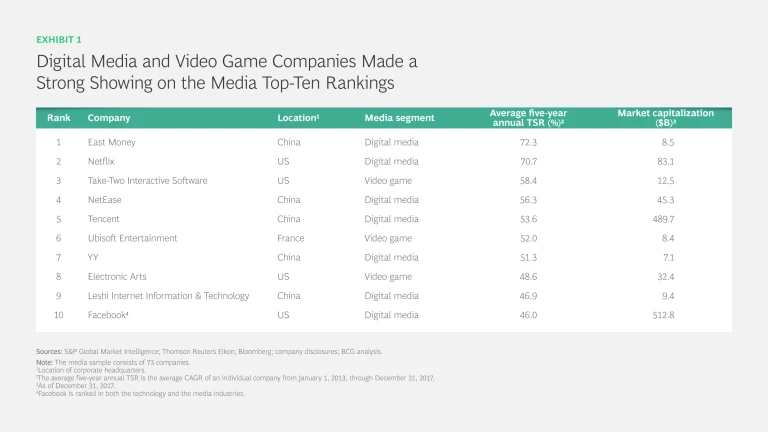

Media is a very volatile industry, yet paradoxically, its aggregate returns have been relatively stable. From 2013 through 2017, the media companies in our study have a median five-year annual TSR of 21%—a slight increase from our previous report, which covered the period from 2011 through 2015. Once again, Chinese companies make a strong showing in the five-year TSR rankings, holding five of the top ten positions. Their performance tracks the continuing growth of the Chinese internet market; spending reached nearly $1 trillion in 2016, second only to the US internet market.

But when we looked at individual segments, sharp differences in performance—and even some shifting tides—emerged. Digital media has had a particularly good run. (See Exhibit 1.)

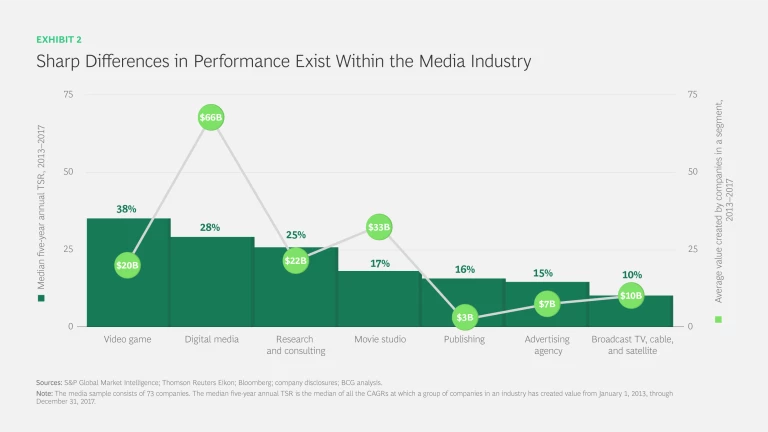

Its median five-year annual TSR of 28% surpasses that of a host of more traditional segments, including movie studio (17%), publishing (16%), advertising agency (15%), and broadcast TV, cable, and satellite (10%). (See Exhibit 2.)

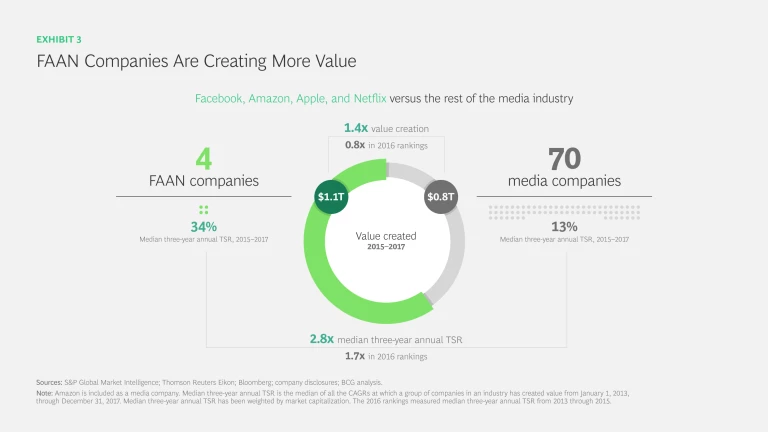

An analysis of absolute value creation reveals even more starkly the ascendency of digital natives. Indeed, the numbers underscore the continued and growing dominance of Facebook, Alphabet, Amazon, and Netflix (FAAN). This quartet generated $1.1 trillion in value in the three-year period from 2015 through 2017—or 140% as much as all other analyzed media companies combined. In our previous report, which looked at the three-year period from 2013 through 2015, the FAAN companies generated a “mere” 80% of the value created by the rest of the media companies. (A three-year period was used since Facebook’s initial public offering was May 2012.) (See Exhibit 3.)

When it comes to value creation, the how is as significant as the how much, if not more so. The story of two FAAN companies shows why this is true. They created massive moats around resilient business models, becoming, in effect, kings without apparent heirs, challengers, or usurpers.

In the digital world, the various types of advertising models cover a wide spectrum—the so-called barbell of advertising—from low-touch solutions, such as programmatic advertising and analytics-based targeting, to high-touch formats, such as branded content and custom-tailored advertising. Facebook and Alphabet, Google’s parent, achieved dominance in digital advertising spending by focusing on models that used their strengths: high-traffic platforms, strong analytics and programmatic capabilities, and the enormous amount of user data generated by their platforms. This approach led the two companies to capture nearly 60% of all digital advertising spending in 2016. Other media companies can spark success by identifying the advertising models along the barbell that fit them best and then building the capabilities that let them run faster and further than the competition.

Moats aren’t the province of only the FAAN companies. Consider Tencent. In seven of the past nine TMT Value Creators reports, the company has been among the cross-industry top ten in terms of average five-year annual TSR. Messaging platforms WeChat and QQ are the core of an ecosystem of integrated services—including e-payments and mobile gaming—that Tencent monetizes.

Companies can spark success by building the capabilities that let them run faster and further than the competition.

Traditional Companies Can Be Winners, Too

In the digital era, success in media is about building these kinds of unassailable castles. But it’s a mistake to think that the concept applies only to digital natives. No matter the media segment, incumbents can establish strong positions in the digital world to spark and sustain value creation.

The New York Times Company is a good success story for publishing. It has strengthened the subscription model of its newspaper by using an important asset—high-quality content—and new digital enablers. The paper’s newsroom is organized to drive its digital agenda and focused on digital formats and content. And the company is analyzing reader data to better understand the kind of content that subscribers want to see. The payoff has been significant: Digital subscription revenue rose 46% from October 1, 2016, through September 30, 2017. In addition, the number of digital subscribers increased by 59% during the same period.

Some traditional media companies are using yet another asset—their large base of customers—to build moats and drive value creation. New advertising models are enabling these companies to monetize customer data. For example, 21st Century Fox, Time Warner, and Viacom are working together on a platform that will help them use insights from their data to sell targeted advertising.

Some traditional media companies are using their large base of customers to drive value creation.

We’re also seeing media players building castles through M&A. Consider The Walt Disney Company. In December 2017, Disney announced its intent to acquire the bulk of 21st Century Fox’s film and TV assets—as well as Fox’s ownership stakes in over the top (OTT) providers Hulu and Roku—for $52.4 bil- lion. This is a deal that can readily be seen as a direct attempt to build global scale and counter Netflix’s domination in the subscription video-on-demand market. The deal gives Disney an expanded library of content for its own video service, and conceivably, the company could keep this content off Netflix’s service. The deal also makes Disney the majority owner of Hulu, an established platform that the company could use to attract OTT subscribers and further monetize its content.

Disney isn’t the only major player to look to M&A to build or expand its online foothold. Warner Bros. Entertainment has invested in subscription platforms by acquiring Drama-Fever—an online service that originally focused only on South Korean dramas but now features content from across the globe—as well as the gaming-oriented online video network Machinima.

Another noteworthy segment is the video game segment. Although it does not have giants such as Facebook or Google generating enormous absolute value, video game companies have the highest median five-year annual TSR at 38%. Traditionally, such performance would come with a caveat: video game TSR has historically been event-driven, or cyclical. A few big hits, and a company’s performance improves dramatically; a few misses, and TSR suffers. But in the five-year period from 2013 through 2017, the business model of video game leaders, such as Electronic Arts, Take-Two Interactive Software, and Ubisoft Entertainment, has evolved to seek more stable sources of revenue. Whereas their traditional model was to sell PC and console games that were, for buyers, a one-time purchase, these companies are now emphasizing recurring digital sales—through in-app purchases, subscription-based online and mobile games, or microtransactions, or a combination of these business models.

Although it may be too soon to say that the video game segment will be less cyclical in the future, some companies are clearly seeing a shift from physical-based revenue (stemming from in-store sales of boxed games) to digital-based revenue. Take-Two—home of the storied Grand Theft Auto franchise and the highest-ranked video game company on the media TSR top-ten list—increased its digital revenue from 13% of total revenue in 2012 to 57% in 2017. At Electronic Arts, digital revenue increased more than 30% from 2015 through 2017 and accounted for 59% of total revenue in 2017.

For most traditional media companies, one of the most pressing challenges is to integrate the digital and physical worlds. To do this well, companies must understand customers’ needs and preferences and tailor products, platforms, and features accordingly.

Companies also need to push innovation out to the customer quickly. Using digital enablers can help. Live Nation, for instance, employs agile methodologies and a cloud-based IT platform to develop and deploy feature changes rapidly. Netflix, meanwhile, is a case study in how to use data and analytics to better make personalized recommendations. (See “ Media Companies Must Reimagine Their Data for a Digital World ,” BCG article, September 2017.) The result has been a growing lineup of popular and award-winning original programming. In 2017, only HBO had more Emmy Award nominations than Netflix.

Traditional media companies have been challenged, sometimes greatly, by digital and the new Goliaths this era has born. Yet there are success stories, too—companies that reoriented their business models, “rightsized” their cost bases, and shaped their portfolios toward growth. In doing so, these companies have transformed themselves—and their future.