This article is part of the series Decoding Global Talent 2018 . The series is based on a survey of 366,000 people in 197 countries by The Boston Consulting Group, The Network, and (in the US) Nexxt.

F our years ago, someone setting out from Latin America to improve his life—making a journey along what demographers call the South-North corridor—might have prioritized Los Angeles or Miami as a destination. A person from the Philippines or Vietnam might have set her sights on San Francisco or New York. The US offered many options for people who were looking for a brighter future. If you were in one of these countries and ambitious, America was a place you thought about.

The US is still a popular destination, but it has slipped, relative to others, in a dozen or so countries where it was previously number one. In those countries, the US is now the number-two or number-three work destination, according to a survey by BCG and The Network.

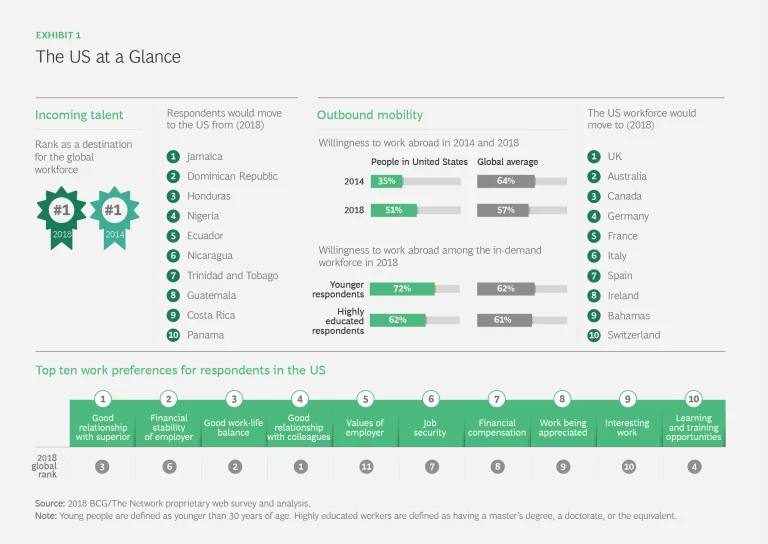

The falloff in enthusiasm for the US in certain regions hasn’t knocked the country from its perch as the number-one work destination overall. (See Exhibit 1.)

And it doesn’t extend to some of the best-known US cities. New York is still the world’s second most popular work destination (after London) as far as survey respondents are concerned, and Los Angeles, Washington, Chicago, and Boston all rank higher as work destinations now than they did in 2014.

Read more about the featured countries

Read more about the featured countries

- Germany Rises to Number Two as a Work Destination

- The UK Slips as a Hot Spot for Global Talent

- France Remains a Top Draw but Still Needs More People

- Switzerland’s Appeal Endures Despite a Dip

- Chinese Residents Are Staying Put for Work

- Russia Faces a Talent Conundrum

- Turkey’s Employers Must Capitalize on Ambitious Talent

Moreover, the shift in attitude toward the US is barely detectable in some big countries. People in Brazil, Germany, South Africa, and Canada still rank the US first among work destinations, as they did in 2014.

However, there is growing interest in other destinations and a different perception about the US at a time when the immigration debate in America has become more polarized.

For instance, the US’s relative appeal as a work destination has fallen in India, Mexico, and the The UK Slips as a Hot Spot for Global Talent . People in those three countries are switching their favor to other English-speaking destinations with assets similar to those of the US but where there is less of a concern that opportunities for foreigners could shrink. Of the alternatives to the US, Canada is now the most common for people in many countries. Ghanaians, Jamaicans, and Trinidadians and Tobagonians are among the people who put Canada ahead of the US today, but didn’t four years ago.

Another notable change from 2014 involves the percentage of the US workforce that says it would consider a job elsewhere. As a group, people in America are still below (by 6 percentage points) the global average in their willingness to work abroad. But willingness to work abroad is no longer a rare attitude in America.

Fifty-one percent of US respondents now say they would consider a job abroad, a big jump from the 35% who said they were open to this in 2014. Willingness to work abroad is particularly high among Americans younger than 30 and Americans with master’s or doctoral degrees.

We interviewed Jesse McLain, 60, who is among the latter. With a doctorate from a theological seminary, McLain does charitable and development work in Haiti, while living part-time in the US and teaching religion online. “I see a lot of Americans seeking foreign jobs due to either unique skills they possess or because of unique job opportunities in other places,” McLain says. He adds that his oldest son “is looking at jobs in South America because of the high pay for experienced oilfield workers down there.”

The foreign country that the most Americans would move to for work is the UK, according to the survey. Australia and Canada are the second- and third-most-popular work destinations for mobile Americans—choices perhaps influenced by cultural and language affinities.

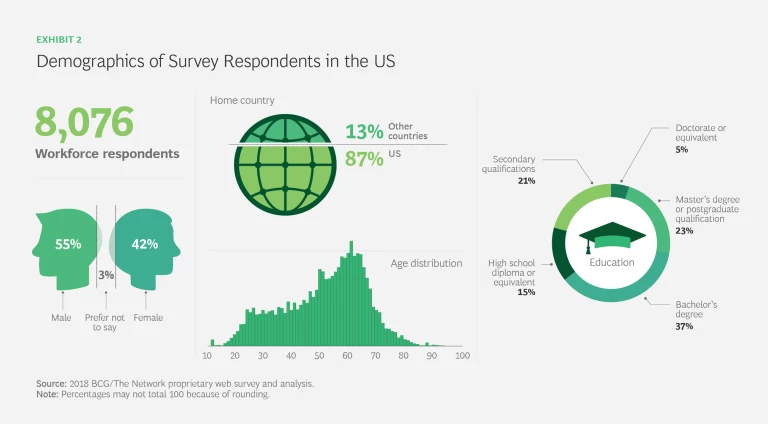

In their workplace preferences, people in America put a higher-than-average emphasis on the financial stability and values of their employer. This may be related to the relatively scant worker protections in the US compared with other countries and the fact that the US government doesn’t often intervene to save jobs. Otherwise, US-based survey respondents (see Exhibit 2 for more on how they break down) are similar to people elsewhere in favoring environments that foster good working relationships and afford them a work-life balance.

Even if the US has slipped in attractiveness compared with some other work destinations in the last four years, decades of mostly open immigration policies have made the US workforce one of the world’s most internationally diverse. That diversity remains a big advantage for American companies.

International diversity remains a big advantage for American companies.

Deepa Nair can attest to this. Nair, 28, came to the US two years ago from her native India and is now living in Atlanta with her husband. After an 18-month wait to get work authorization, she is looking for a job in her field of software development.

“In India, you only see Indians,” Nair says. “Here you have people from so many different places. You feel the warmth from people here.”

The US economy and US companies have historically benefited from their destination status for globally mobile talent. But the gap has narrowed. US economic policymakers and company executives will have to rethink who they go after and how, if they are to sustain their advantage in an increasingly global marketplace for talent.