“Vitality shows in not only the ability to persist but the ability to start over.” — F. Scott Fitzgerald

“How do you keep the vitality of day one, even inside a large organization?” — Jeff Bezos

Leadership has its benefits—scale, knowledge, influence, and financial stability among them. But our research shows that as companies age and grow, incumbents increasingly focus on internal matters, have more difficulty freeing themselves from legacy businesses and approaches, and progressively shift their priorities toward running—rather than reinventing—the business. Nontraditional competitors, disruptive technologies, and new business models are making corporate reinvention a critical priority.

How can legacy leaders remain vital—to preserve and develop their capacity for growth, risk taking, innovation, and long-term success? In creating a quantitative measure of corporate vitality and its underlying drivers, we hope to provide a working framework of what matters when managing the balance between delivering near-term execution and investing in the future. The drive to maintain vitality has organizational, financial, and cultural levers—all of which reinforce each other.

VITALITY: A NECESSITY FOR LONG-TERM GROWTH

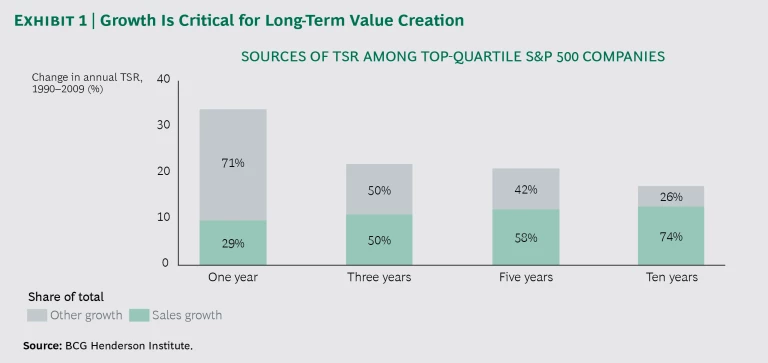

The challenge is straightforward: growth is critical for sustained value creation. In the short term, companies can create value by optimizing costs or assets or by building investors’ expectations. Yet in the long run, most value creation comes from top-line growth, which accounts for 74% of total shareholder return of S&P 500 top-quartile-performing companies over a ten-year period. (See Exhibit 1.)

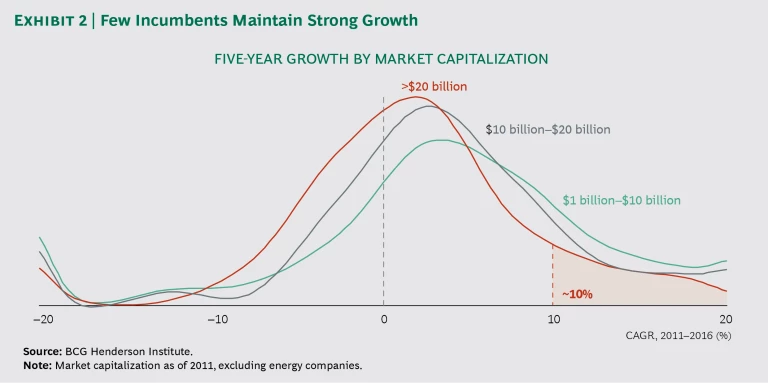

The good news is that achieving sustainable growth is still possible for today’s incumbents. Approximately 10% of large US companies are growing at double-digit rates. (See Exhibit 2.) Among that 10%, many—such as Visa and Mastercard (credit cards), Hilton (hotels), Constellation Brands (alcoholic beverages), and O'Reilly (auto parts)—are from nontech industries. What is their secret?

In today’s rapidly changing environment—with elevated political, social, and technological uncertainty—what will make a company thrive tomorrow is different from what makes it succeed today. Current performance is less and less predictive, and an overreliance on backward-looking metrics can be deceptive. Many of today’s large incumbents are vulnerable, even if they have a solid track record of past performance.

And abrupt failures happen increasingly frequently—think Kodak or Blockbuster—in no small part because of the risk of digital disruption. Even when their positions seem comfortable, incumbents need to create a sense of urgency and preemptively address the requirements to sustained success. They must develop their capacity for growth and reinvention. This is what we call vitality.

We are able to measure vitality by using BCG’s proprietary methodology behind the Fortune Future 50—the result of a two-year research partnership between BCG and Fortune magazine. This index ranks the most vital US-listed companies. To build it, we collected all theories purporting to explain the ability of a company to grow and we associated them with measurable variables. We then tested those theories against historical data and only kept the variables that had a measurable and robust impact on long-term revenue growth. As expected, the age and size of a company have a negative impact on growth—confirming that the more established the incumbent, the harder it is to remain vital.

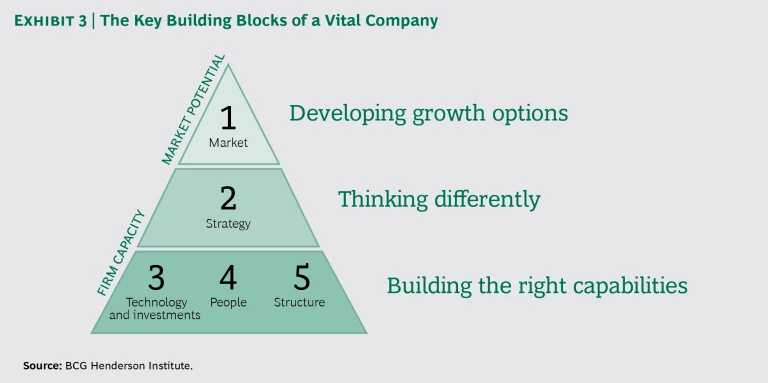

We were also able to identify these key building blocks for vital companies (see Exhibit 3):

- The Ability to Continuously Develop Future Growth Options. This is the main driver of vitality for incumbents. It can be achieved by constantly renewing a pipeline of potential bets, catalyzed by an entrepreneurial spirit that facilitates ongoing exploration—even when the fruits of a previous exploration are in the midst of paying off.

- The Willingness of Leadership to Think Differently About Strategy. Unlike the companies that are narrowly focused on maximizing short-term total shareholder return, leaders of vital incumbents are focused on exploration and have a long-term orientation. We know this because we trained a natural-language-processing algorithm on 70,000 annual reports filed by companies to the US Securities and Exchange Commission. This enabled us to detect future-oriented strategic thinking and demonstrate that it is positively correlated with long-term revenue growth.

Furthermore, leaders must drive this long-term orientation into the organization, by promoting "day one" mentality, for example, and allocating sufficient resources to place and evolve bets. Thornton Tomasetti, a leading engineering firm, embraces this mindset fully in its five-year strategic vision: “We keep our eyes and minds open, test new ideas thoroughly, and invest selectively and quickly.”

- The Determination to Build the Right Capabilities. Strategy and execution cannot be separated from one another, and to be vital, companies need to build the right capabilities—especially in relation to technology and people. Vital incumbents are able to stay on top of relevant emerging technology, in part by using transformative (as opposed to scale- and cost-driven) M&A moves when needed. They employ “post-merger rejuvenation” to acquire smaller, faster-growing companies and inject new capabilities and stimulate growth.

In addition, the most vital companies maintain a diverse and youthful organization at all levels—including within the boardroom—by providing leadership opportunities for upcoming talent. Our research shows that there is a statistically significant relationship between innovation and diversity in its many dimensions.

THE CHALLENGE OF AMBIDEXTERITY

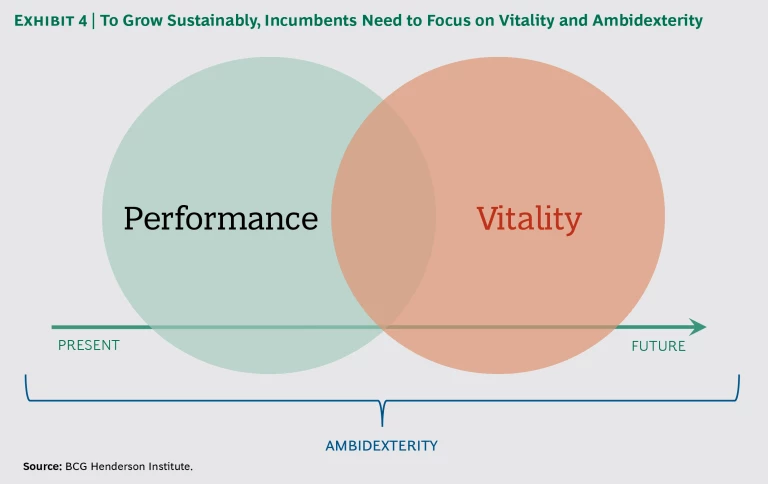

Vitality alone is not enough for incumbents to thrive and grow sustainably. Overperformance within the core business is also necessary in order to finance vitality. Even if having deeper pockets is a potential advantage for incumbents, they must still work at realizing ambidexterity—being able to run and reinvent the company at the same time. (See Exhibit 4.)

Embracing the contradiction of ambidexterity—optimizing current performance while building the potential for long-term growth—is difficult for any company. And this is especially true for incumbents, where the current business model can easily dominate resources, talent, and thinking. The most obvious impediment to ambidexterity for incumbents is sheer size, and there are several factors that can turn the benefits of scale into the burden of inertia.

First, as companies grow older, successful behaviors from the past tend to ossify into fixed thinking and processes, as well as specialized talent. Leaders can be part of the problem, since they are likely to be associated with, and personally invested in, the current model of success.

Second, slower decision making and an aversion to risk can be harmful in their own right and also make it more difficult to attract and retain entrepreneurial talent.

Third, companies focused on exploitation—or current performance—have a tendency toward financialization: decisions are based predominantly on financial metrics, such as profitability or earnings per share. Exploration might look unattractive or poorly defined when judged by the crisp financial metrics possible for a mature business. The risk-weighted returns on individual exploratory investments might be low or difficult to quantify, but when considered collectively they can be essential for the continued existence of the company. The best way to assess whether a bet is worth the risk may sometimes be to compare it with a scenario of the eventual demise of the cash-cow business.

Finally, having a strong TSR track record and a generous dividend policy can also increase investors’ expectations of continued short-term cash returns. This can narrow management focus toward optimizing short-term financial wins over long-term investments—that is, performance over vitality.

THREE STEPS TOWARD ENHANCING VITALITY

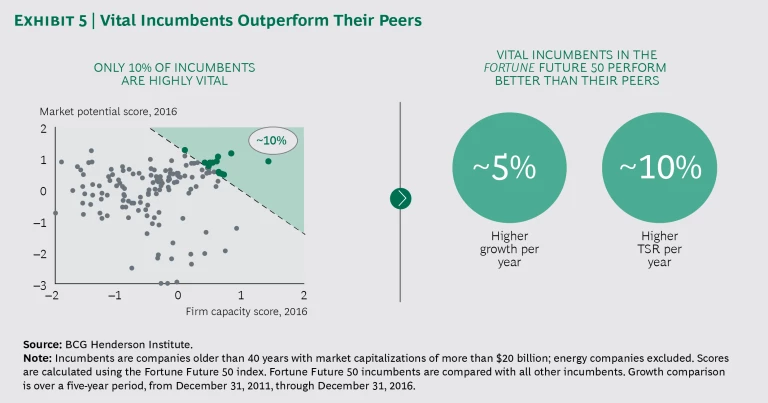

Building vitality is essential for established companies that want to survive and thrive. Even when measuring short-term health, vital companies are in the lead. From 2011 through 2016, the top-10% most vital incumbents in the Fortune Future 50 outperformed their peers by 5% per year in growth and 10% per year in TSR. (See Exhibit 5.)

To become a more vital organization, company leaders must follow three steps.

Step one: Assess your current vitality. Establish a clear understanding of your starting point from the outside in (by using the Fortune Future 50 methodology) and from the inside out, by answering the following questions:

- What is the growth potential of your pipeline of “future bets”?

- To what extent does your strategy encompass long-term exploration?

- What are you doing to develop leading capabilities in technology?

- Are you willing to challenge the approaches and beliefs that have historically made you successful?

- Are you taking a risk on new talent, and is your organization cognitively diverse?

Step two: Strengthen or renew sources of vitality. This can include a range of measures:

- Create a portfolio of growth options. Companies need to have a balanced portfolio of bets on different timescales. In order to do this, they must develop a tolerance for failure and create incentives for entrepreneurship.

Recruit, one of Japan’s most successful large companies in recent times (20% growth per year in the last five years), embodies this culture perfectly. Through its New Ring program, which receives more than 1,000 proposals every year, Recruit allows any employee, sometimes in collaboration with outside stakeholders, to propose starting a new business in line with the company’s hybrid ecosystem philosophy. By doing so, leadership is able to systematically identify, nurture, and celebrate entrepreneurial talent within the company.

- Build adaptive and shaping capabilities. Incumbents often have strongly developed capabilities to deal with classical strategy and execution, which is powerful and necessary in mature businesses. But the uncertain environment of many emerging businesses requires a more adaptive approach to strategy and execution. This requires, for instance, a system to seed, test, and scale new ideas in a rapid and iterative fashion.

In addition, shaping capabilities enable incumbents to influence their business environment rather than be at its mercy. These include the ability to conceive and create new markets, mobilize others around new win-win propositions, create and orchestrate collaborative ecosystems, and allow these ecosystems to evolve as circumstances change. A famous example is Apple’s transformation of the smartphone market. It triumphed against incumbent players by building an ecosystem of collaborators that together could create a smartphone and a rich library of software, instead of attempting to build everything internally.

- Invest in technology. Technology capabilities are even more important than one might imagine. Our analysis shows that a common feature of the least vital incumbents is the weakness of their technology portfolio. At the other end of the spectrum, Mastercard (number 14 on the Fortune Future 50 ranking) illustrates how having a strong emphasis on technology can help incumbents evolve and thrive. Mastercard has shifted from being a payments company to also becoming a technology leader, as expressed through its mission: “We’re providing the technology that’s leading the way toward a world beyond cash.”

- Maintain dynamism and diversity. Compositional diversity is not enough. Diversity of employee backgrounds favors but does not guarantee innovation. Also necessary is an environment that is conducive to encouraging diversity of thought and a collision of ideas. Thornton Tomasetti’s five-year strategic vision states, “Everyone contributes to learning, and new ideas are given a chance.”

There are several other ways to broaden an organization’s thinking, including maverick scans and scenario-based stress tests. In addition, using a flat, adaptive structure as well as team-based leadership helps to foster further diversity of thought. The more fluid an organization, the more it allows people to self-organize around new ideas and better ways of doing things. For example, Morningstar Foods has adopted an extreme “no-hierarchy” structure that allows for “a lot of spontaneous innovation and ideas for change [to] come from unusual places.”

- Self-disrupt before being disrupted. Recent research shows that only one-third of incumbents facing disruption survive and thrive. Survival depends on preemptively creating a sense of urgency and a will to self-disrupt before being disrupted.

- Self-disruption can either happen internally or through M&A moves. The former requires boldly rethinking the business model, while building on existing advantages. Restructuring to separate or divest legacy businesses can be part of the solution, too. Otherwise, incumbents can look outside and consider acquiring—or acqui-hiring—disruptive and emerging companies. This can result in post-merger rejuvenation, as happened to Disney when it used Pixar as a stimulus for self-disruption, learning, and ultimately growth.

Step three: Lead with ambidexterity, according to the following checklist:

- Choose the right approach to strategy for each part of the business. Mature core businesses require very different approaches to strategy and execution than emerging ones do. As laid out in Your Strategy Needs a Strategy, the approach to strategy and execution needs to be flexed, based on the business environment that each part of the business faces.

- Structure to enable multiple approaches. Ambidexterity enables firms to deploy different approaches to strategy simultaneously in each part of the business and manage the resulting contradictions. As a result, ambidextrous firms are able to perform strongly and be vital at the same time. This is particularly challenging for incumbents, but adopting the right organizational structure can help.

The Chinese consumer-goods company Haier, which went from near-bankruptcy in the 1980s to its global market-leader position today, is a powerful example of how adjusting organizational structure can be the path to ambidexterity. How did it do it? In an effort to improve its ability to deliver customer value, the conglomerate flattened its organization and developed 2,000 self-governing units. This drastic change enabled each unit to function like an autonomous company and use an approach to strategy tailored to its specific situation.

- Manage the “investor story.” As a response to short-term-oriented investor pressures, incumbent leadership needs to convince investors that current performance is on track and the business case for future investment is sound. This is a very important step in buying time and permission to strengthen vitality.

Andrew Wilson, CEO of Electronic Arts (number 25 in the Fortune 50), gave a presentation to investors that exemplifies how a forward-looking vision should be communicated. He started by emphasizing the positive short-term and midterm financial outlook driven by the core portfolio and then laid out an inspirational long-term-growth strategy focused on new portfolio bets, new geographic expansion, and business model innovation.

Incumbent businesses are at a crossroads. Short-term performance is strong overall, but political, social, and technological change and uncertainty cloud the horizon. Thus, the prize for being vital is more valuable than ever. With equal emphasis on performance and vitality, companies can thrive into the future.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights.