The last decade was trying for Latin America, but it also brought some reasons for optimism. Millions of households across the region entered the middle class, and living standards improved. But many of these gains were fueled by a commodities boom that has since waned. For Latin America to get on the road to sustained economic growth , the region will need a significant increase in investment and productivity.

One group of companies, in sectors as diverse as consumer goods, telecommunications, and infrastructure, could prove pivotal in enabling Latin America to achieve these goals. The multilatinas, as they are called, have generated exceptional growth and have operations beyond their national borders. From 2008 through 2016, the multilatinas that we have identified and tracked—the “BCG multilatinas”—registered annual revenue growth of 5.2% as measured in US dollars, around three times higher than the average for all large Latin American companies. Now, with the region’s economies showing signs of stability and renewed growth, we believe that the multilatinas are well positioned to help lift Latin America to the next level.

From 2008–2016, the multilatinas registered annual revenue growth around three times higher than the average for all large Latin American companies.

In addition to the tangible benefits that the multilatinas are bringing to a region of 20 nations and more than 600 million people, these companies are important sources of innovation and human capital development. They are at the forefront when it comes to creating new value in services, responding to the demands of a growing middle class, reaching borderless communities of connected customers, and serving as valuable nodes in the ecosystems of other global enterprises. The multilatinas can also play a pivotal role in enabling Latin America to thrive in a shifting global landscape. At a time when the US, one of the region’s most important partners, is becoming more isolationist, the multilatinas can serve as bridges to other corners of the world and exemplify the benefits of integrating regional economies.

Multilatinas Then and Now

BCG published its first list of 100 multilatinas in 2009. (See The 2009 Multilatinas: A Fresh Look at Latin America and How a New Breed of Competitors Are Reshaping the Business Landscape , BCG report, September 2009.) For our 2018 list, we added two new types of companies: financial companies and a group of dynamic technology companies that we call technolatinas.

The composition of this year’s list reflects some of the profound transformations that have occurred in the region’s economies since our earlier study. Among the key findings this year, compared with those of 2009:

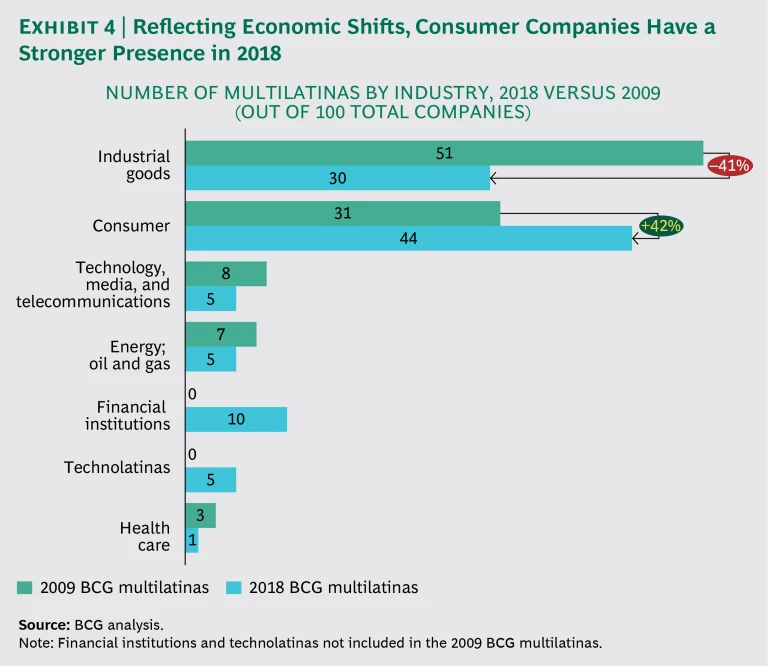

- A Larger Presence of Consumer Companies. The share of multilatinas specializing in consumer goods and services that meet the needs of the expanding middle class increased from 31% to 44%. The number of commodity companies fell from 12 to 7, largely owing to the downturn in commodity prices.

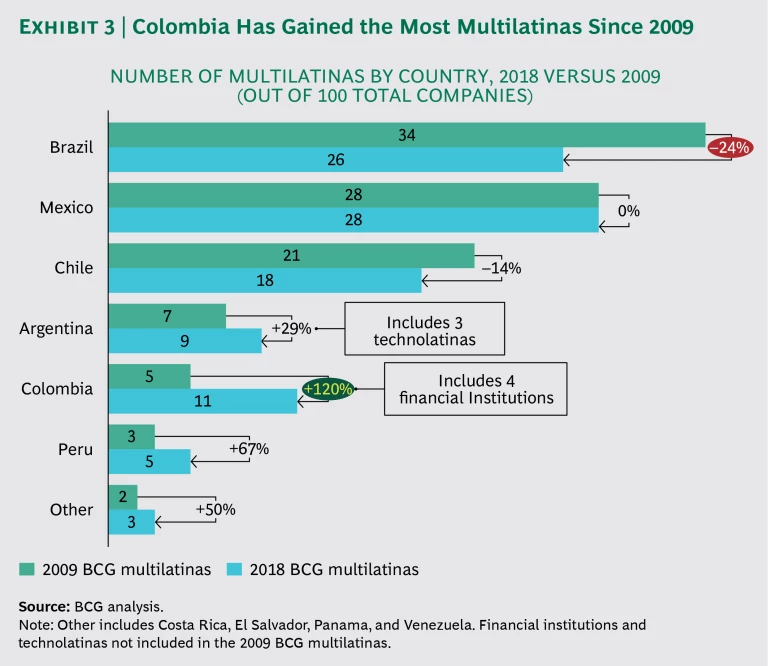

- Greater Geographical Diversity. Although companies from Brazil, Chile, and Mexico still dominate the list in 2018, there are more companies from Argentina, Colombia, and Peru—in large part because of the inclusion of financial institutions and technolatinas. Companies from Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Panama also joined the list.

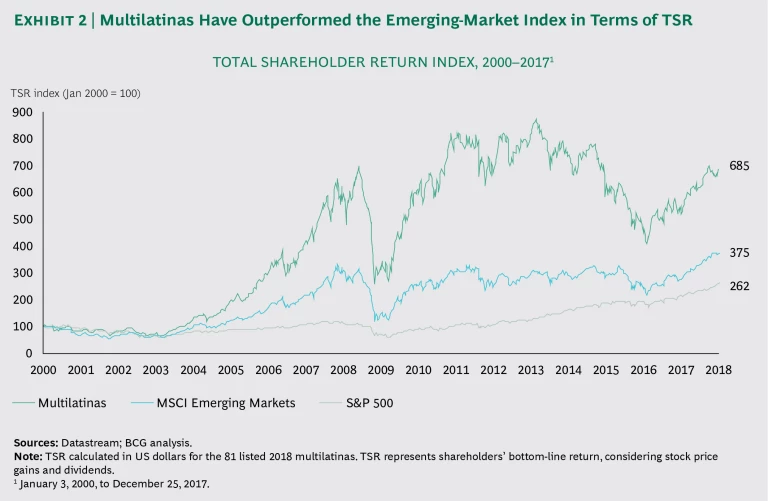

- Superior Value Creation. The average total shareholder return—a broad measure of company stock performance—of the BCG multilatinas increased 12% per year from 2000 through 2016, far outpacing the 8% average TSR of emerging-market companies as a whole.

- Strong Contribution to Job Creation. Employment at multilatinas expanded by 2.6% annually from 2013 through 2016, above the regional average of only 0.3% per year for the same period.

The Economic Context

Despite these companies’ success, Latin America has been losing ground in the global economy: its share of global GDP shrank from 8.6% in 2009 to 7.7% today. This has occurred at a time when emerging markets in general have boosted their share of global economic output from 33% to more than 50%, according to the International Monetary Fund. Economic volatility in many Latin American economies has also been much fiercer than in most of the world, damaging investor confidence.

Although Latin America still generally underperforms other emerging markets, the picture is starting to improve.

Latin America enjoyed strong GDP growth until the 2008–2009 global recession, and the region has since struggled to sustain economic momentum. Commodity prices started falling in 2014; fiscal crises, political turmoil, insufficient public and private investment, and declining consumption fueled recession, and market turmoil compounded the problems. Countries such as Brazil and Argentina experienced major setbacks, while others, such as Chile, Colombia, and Peru, continued to grow but at slower rates.

In addition, inadequate investment over the years in education and infrastructure has left several Latin American nations without a strong foundation for growth and diversification beyond resource-based industries. (See Brazil: Confronting the Productivity Challenge , BCG report, January 2013.) In global benchmarks of government efficiency, government regulatory burdens, and the effectiveness of investment incentives, Latin America lags well behind many other emerging markets. Although this also varies from one country to the next, in general terms the region has yet to fulfill many overdue economic reforms.

Although Latin America still generally underperforms other emerging markets, the picture is starting to improve. Brazil and Argentina are showing signs of recovery, and GDP growth across the region is projected to average 2.7% through 2021.

Latin America still possesses a number of assets that make it an attractive growth market. For starters, the region has a combined nominal GDP of $5.3 trillion, greater than that of the ASEAN economies, India, and the Middle East plus Africa. It is also a $3.5 trillion consumer market. Indeed, per capita annual private consumption is higher in Latin America than in China or Russia.

Recent recessions in some nations have pushed many households back into poverty, but 35% of the regional population is still in the middle class—a significant increase since 2009, when it stood at 28%. The distribution of income, which has historically been very unequal in Latin America, has been improving slowly but steadily. The average regional Gini index—a measure of the gap between the highest-income earners and the lowest—has narrowed by an average of 1 percentage point annually since 2009.

From 2014 through 2016, Latin America drew an average of $184 billion in foreign direct investment annually— close to China’s level.

Furthermore, 95% of Latin Americans speak Spanish or Portuguese and share similar values and cultural influences. This helps businesses that wish to collaborate and engage with customers across borders. Latin America remains rich in natural resources, accounting for 14% of the world’s agricultural land, 15% of oil reserves, 21% of forests, 28% of available water, 54% of copper production, and 66% of lithium reserves.

The growing commitment to trade and investment liberalization by some Latin American governments, despite growing protectionism in the US and elsewhere, also favors the region and its multilatinas. The region’s recent tilt toward openness is expected to help increase both imports and exports, which have grown by roughly 30% since 2009. Greater openness is also making Latin America an attractive destination for foreign direct investment. From 2014 through 2016, the region drew an average of $184 billion in FDI annually—close to China’s level—compared with $126 billion in the ASEAN economies and $41 billion in India. Approximately $30 billion of that amount came from China alone—double the sum from 2003 through 2009. The automotive, metals, and communications sectors have been among the chief Chinese investment targets.

A resilient private sector is arguably among Latin America’s most valuable assets. Around 80% of the region’s companies, both big and small, are family owned. These enterprises employed 70% of the workforce as of 2014. In our experience, family-owned businesses focus on resilience. Their earnings may be slightly lower than those of their peers during good times, but they outperform during downturns. They know how to navigate complex business environments and have a long-term commitment that enables them to ride out business cycles. Despite being controlled by families, many leading Latin American companies are run by trained professionals who instill modern management methods and practices. The growth that some of them have enjoyed in the past decade is pushing them to seek higher levels of professionalization. This is especially true for the multilatinas.

The 2018 BCG Multilatinas

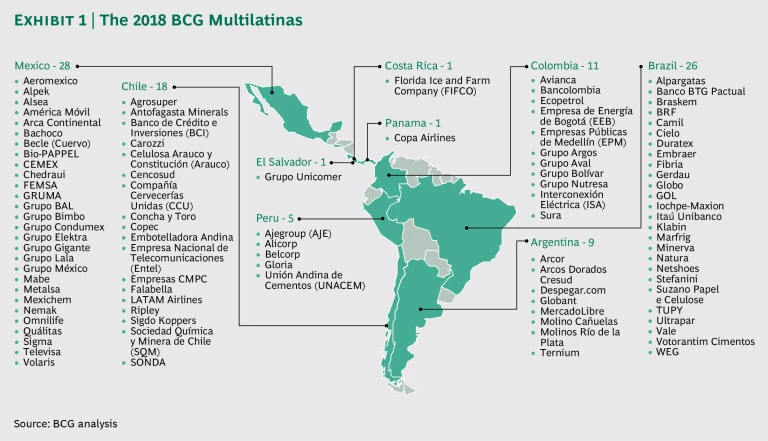

We began by analyzing more than 5,000 companies with operations in Latin America that have more than $1 billion in revenue and that have grown faster than the regional average and operate beyond their national borders. The technolatinas included in our latest study are Latin America-based companies in tech-related businesses that compete internationally and had more than $300 million in revenue in 2016. (See Exhibit 1.)

The multilatinas significantly outperformed their regional peers during the study period. Their 5.2% annual growth rate from 2008 through 2016 (US dollars) compares with a 1.8% rate for all Latin American companies with more than $1 billion in annual revenue. As a group, these companies excel at creating value. From 2000 through 2017, despite periods of volatility, their average total shareholder return increased 685%. That compares with a 375% rise in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.

Roughly half of the 2009 multilatinas did not make the 2018 list. Most dropped off because they failed to maintain strong enough growth or profitability. Ten were involved in mergers and acquisitions, although three of those reappeared on the 2018 list as other entities. Other companies no longer had a sufficient international footprint.

A More Diverse Geographic Mix

There were some interesting shifts in the geographic distribution of the BCG multilatinas. In 2009, Brazil. Chile, and Mexico accounted for three-fifths of companies on the list. This year, companies are more spread out, with greater representation from Argentina, Colombia, and Peru; companies from Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Panama also made the cut.

Chile continues to outperform. Although it accounts for only 5% of Latin America’s GDP, Chile is home to 18% of the BCG multilatinas. Over the past few years, it has been the most successful Latin American nation at translating economic growth into improved well-being for its citizens, according to BCG’s Sustainable Economic Development Assessment. Chile also scores high on the World Economic Forum’s global competitiveness rankings in higher education and infrastructure.

Nine Argentinian companies made the 2018 multilatinas list, despite that nation’s deep economic troubles. Three are technolatinas: Despegar.com, Globant, and MercadoLibre. MercadoLibre is one of the region’s tech success stories. Founded in 1999, it is a true unicorn, achieving a current market capitalization of more than $15 billion. Argentina’s strong education system, regional leadership in internet usage, development of tech hubs and collaborative work spaces, and government funding for technology accelerators and startups have all contributed to its strong tech sector. Nonetheless, considering the size of its GDP, Argentina remains underrepresented on the multilatinas list.

The strong representation from Colombia—11 multilatinas compared with 5 in 2009—can be largely attributed to the strength and regional breadth of its financial sector. (See Exhibit 3.) Financial services account for 36% of Colombian multilatinas, compared with 12% of Brazil’s, 7% of Mexico’s, and just 6% of Chile’s. Colombia has a strong reputation for trustworthiness in the region’s business community and high confidence in its financial system, according to the World Economic Forum. Colombian institutions such as Bancolombia and Banco de Bogotá (Grupo Aval) have been particularly successful at expanding across Central America.

Mexico’s presence on the list remains stable with 28 multilatinas. Brazil accounts for around 25% of these companies, compared with 34% in 2009, the largest drop among countries. Brazil was hit hardest by recent economic and political instability. Still, 70% of multilatinas with revenues above $5 billion are either Brazilian or Mexican.

Rising Latin American Growth Sectors

Shifts in the growth dynamics of Latin American economies are reflected in the latest list. The number of service companies rose from 26 in 2009 to 41 this year, largely owing to the addition of financial institutions and technolatinas.

The number of consumer sector multilatinas increased by 39%, to 44. (See Exhibit 4.) This reflects growing consumption by Latin America’s rising middle class. Twenty-nine of those companies sell consumer goods.

The number of commodity companies on the list shrank by 41% to seven, highlighting the fall in international prices for oil and minerals, as well as decreased investment. Health care is the most underrepresented sector among the multilatinas. Most Latin American health care companies are midsize enterprises or subsidiaries of multinationals.

Five Key Success Factors

Our analysis of the BCG multilatinas identified five factors that have enabled these companies to outperform their regional peers and achieve above-average growth.

Connecting More Intimately With Consumers

Multilatinas in consumer segments, in particular, have taken advantage of their strong, recognizable brands and knowledge of the region to build trust and strengthen their relationships with customers.

Many multilatinas are listed among the region’s most valuable brands, judging by the annual BrandZ rankings by research firm Kantar Millward Brown. In Chile, the premium retailer Falabella has consistently ranked as the most valuable brand since 2012, for example, as has Televisa in Mexico and Itaú Unibanco in Brazil. That is particularly important in Latin America, where surveys have found that a higher proportion of consumers than in any other region consistently cite brand recognition as a top reason for buying a product.

A number of multilatinas use customer-centric strategies aimed at improving customer engagement and personalizing their products. Through its regular engagement with consumers via social media, for example, one multilatina in the food sector noticed that a product it was selling in one country was in demand in another Latin American market. The company launched the product there and used social media to promote it. The product sold out in a couple of weeks.

Overcoming Value Chain Complexities

Running a business is particularly challenging in Latin America, where regulatory and fiscal environments can be convoluted, institutions can be complex, and poor infrastructure and long distances can complicate logistics and value chain management.

Multilatinas tend to be better at coping with these challenges. One measure is asset turnover rates, or revenues divided by average assets over a given period. Multilatinas in sectors such as engineering and construction, steel, auto parts, food, and petrochemicals have higher asset turnover rates than those of their competitors. In the oil and gas sector, their asset turnover is around 2.5 times higher than the industry average. In the few sectors where multilatinas lag their regional peers in asset turnover, such as cement and power, the gap is closing.

One Latin American airline illustrates how multilatinas overcome the region’s complexities and improve efficiency. The carrier found that its aircraft were out of service for maintenance 60% longer than anticipated. Because many parts are imported, complex customs clearance processes and high import duties add time and money. Among other initiatives, the carrier revised its governance model to better integrate multidisciplinary teams and developed analytic tools to better predict its use of materials and capacity. As a result, the carrier was able to reduce delays by around 80%.

Orchestrating Innovation Networks

Latin America invests less of its GDP in research and development than any region except South Asia, and very few Latin American companies rank among the global leaders in R&D spending.

Multilatinas tend to invest more in R&D than their peers in the region, resulting in new products and solutions that accelerate growth. Multilatinas account for 13 of Latin America’s top 20 recipients of patents. Natura alone holds over 670 patents. Vale has about 640 and Alpek nearly 600.

Several multilatinas benefit from innovation networks that include their own R&D centers, research partnerships, and small-business incubators. For instance, Brazil’s Braskem developed a polyethylene plastic produced from ethanol sugarcane—a renewable raw material—at one of its technology and innovation centers. This technology enabled Braskem to establish global leadership in bioplastics. Meanwhile, Banco de Crédito e Inversiones (BCI), as part of its digital transformation program, has set up an innovation lab, is publishing an open catalogue of application program interfaces, and is launching Mach, the first open peer-to-peer payments app in Chile.

Merging Like A Pro

Multilatinas invested around $48 billion in mergers and acquisitions from 2009 through 2017, accounting for about 20% of the value of all M&A activity in the region over that period. Such moves have enabled these companies to boost their growth and geographic reach. The merger of TAM Linhas Aéreas and LAN Airlines, for example, resulted in the region’s leading carrier, LATAM Airlines.

Creating value through M&A isn’t easy. But the odds improve as acquirers gain experience. According to our research, the share prices of multilatinas that are serial acquirers have appreciated by almost 70% over the past eight years, compared with a 7% increase for other Latin American frequent buyers.

Multilatinas are more active in cross-border M&A than other companies in Latin America and employ a number of best practices. Several have dedicated teams that follow the acquisition process end to end. Navigating political and regulatory pitfalls, which is challenging in the region despite a common language and cultural heritage, is especially important.

Nurturing Employees To Unleash Talent

Multilatinas are taking a number of actions to overcome skills shortages, which in some Latin American countries are among the most acute in the world. Several have established training programs in partnership with schools. Aerospace manufacturer Embraer, for example, collaborates with Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica. Other companies have created corporate universities, such as MercadoLibre’s MELI Academy.

Positioning for the Future

These five success factors have enabled multilatinas to adapt and succeed through years of economic and political turbulence. But now these companies must hone new advantages to outperform in the decade ahead. The business landscape both within the region and around the world is undergoing profound change. Globalization is being radically redefined by growing economic nationalism and new digital technologies. Global growth is being driven less by physical trade and more by rapidly expanding digital connections among people, businesses, and devices. (See “ The New Globalization: Going Beyond the Rhetoric ,” BCG article, April 2017.)

The implications of these shifts are being felt in Latin America. A decade ago, the region’s growth was propelled primarily by commodities, export manufacturing, domestic consumption by a growing middle class, and the demographic dividend generated by a young, rapidly growing workforce and declining birthrates. While several of these growth drivers will remain relevant, future growth will be increasingly driven by a growing demand for services, the adoption of advanced digital technologies, and the expanding power of global IT platforms. (See “ New Business Models for a New Global Landscape ,” BCG article, November, 2017.)

Multilatinas tend to invest more in R&D than their peers in the region, resulting in new products and solutions that accelerate growth.

To succeed in the next phase of globalization, multilatinas will certainly need to continue building on strengths such as marketing savvy, operational efficiency, M&A skills, innovation, and talent management. But they will also need to develop new capabilities and innovative business models. They will have to master data analytics, digital strategy, artificial intelligence, and the advanced manufacturing systems that make up Industry 4.0. They will also need to make delivery of value-added, customized services and products that meet specific clients’ needs their central goal. And as important offshore markets become more complex and protective, multilatinas must be able to identify new pockets of growth opportunities among borderless markets of digitally connected consumers.

We already see evidence that the multilatinas are adapting. Leading-edge manufacturers are deploying advanced technologies such as blockchain and 3-D printing. Financial services companies and retailers are putting agile work models into practice and transacting more business through digital channels. Consumer product companies are mining big data to codesign products with their customers.

The competitive challenges ahead, both for companies and for Latin America as a whole, are numerous and daunting. But as they have demonstrated over the past decade, the multilatinas have a knack for navigating complexity. They also have the power to push Latin America forward.