The gender pay gap is well documented: women make about 80 cents for every dollar that a man earns. Less well known: the gender investment gap. According to our research, when women business owners pitch their ideas to investors for early-stage capital, they receive significantly less—a disparity that averages more than $1 million—than men. Yet businesses founded by women ultimately deliver higher revenue—more than twice as much per dollar invested—than those founded by men, making women-owned companies better investments for financial backers.

BCG recently partnered with MassChallenge , a US-based global network of accelerators that offers startup businesses access to mentors, industry experts, and other resources. Since its founding in 2010, MassChallenge has backed more than 1,500 businesses, which have raised more than $3 billion in funding and created more than 80,000 jobs. MassChallenge, which neither provides financial support nor takes equity in the businesses it works with, puts significant effort into supporting women entrepreneurs.

Our objective was to see how companies founded by women differ from those founded by men. Our data shows a clear gender gap in new-business funding. We also spoke with investors and women business owners to get a sense of how they perceive the funding status quo. Our findings have clear implications for investors, startup accelerators, and women entrepreneurs seeking backers.

Challenging Numbers

One might think that gender plays no role in the realm of investing in early-stage companies. Investors make calculated decisions that are—or should be—based on business plans and projections. Moreover, a growing body of evidence shows that organizations with a higher percentage of women in leadership roles outperform male-dominated companies. (See “ How Diverse Leadership Teams Boost Innovation ,” BCG article, January 2018.) Unfortunately, however, women-owned companies don’t get the same level of financial backing as those founded by men.

To determine the scope of the funding gap, BCG turned to the detailed data MassChallenge has collected on the startup organizations it has worked with. About 42% of all MassChallenge-accelerated businesses—of all types and in all locations—have had at least one female founder. Aiming to build on the growing proportion of women entrepreneurs, the availability of education and support for them, and the sizable community of women who are business experts, MassChallenge determined that it needed to learn more about how its women entrepreneurs were faring and how the program could better prepare them for future success.

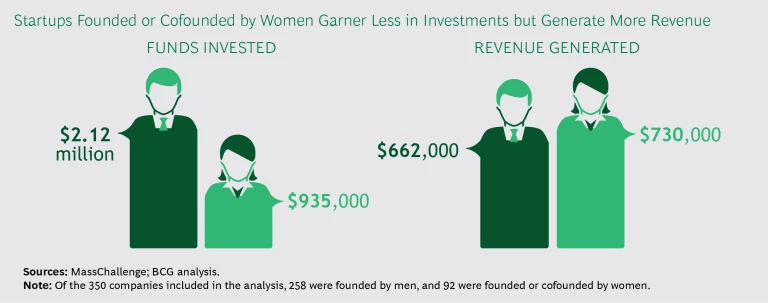

In a review of five years of investment and revenue data, the gender-focused analysis showed a clear funding gap (see the exhibit).

- Investments in companies founded or cofounded by women averaged $935,000, which is less than half the average $2.1 million invested in companies founded by male entrepreneurs.

- Despite this disparity, startups founded and cofounded by women actually performed better over time, generating 10% more in cumulative revenue over a five-year period: $730,000 compared with $662,000.

- In terms of how effectively companies turn a dollar of investment into a dollar of revenue, startups founded and cofounded by women are significantly better financial investments. For every dollar of funding, these startups generated 78 cents, while male-founded startups generated less than half that—just 31 cents.

The findings are statistically significant, and we ruled out factors that could have affected investment amounts, such as education levels of the entrepreneurs and the quality of their pitches. (See the sidebar, “A Closer Look at the Data.”)

A Closer Look at the Data

A Closer Look at the Data

MassChallenge does not provide upfront funding to or take any equity from the startups it works with. But to learn more about its alumni startups’ progress beyond their time in its program, Mass-Challenge surveys them semiannually.

Using the anonymized data, we conducted a regression analysis, initially without controlling for any factors. The results showed that the disparities in external funding awarded to startups were statistically significant and that the disparities were due to gender. We ran a second test, controlling for education levels among business owners. The results of that test also showed that investment levels were lower for women-founded businesses owing to gender and not education. Last, we looked at judges’ scores for each business at the time of its application to MassChallenge and found that there was no significant difference between companies founded by men and those by women: the scores for men-led and women-led startups were similar. Using this as a proxy for quality, we can say that the disparity in funding is not due to qualitative differences in pitches or underlying businesses. Our results strongly suggest that gender plays a significant role.

The results, although disappointing, are not surprising. According to PitchBook Data, since the beginning of 2016, companies with women founders have received only 4.4% of venture capital (VC) deals, and those companies have garnered only about 2% of all capital invested.

Why the Disparity?

To dig deeper, we spoke to women founders, business mentors, and investors, some of whom were not affiliated with MassChallenge. From those conversations, three explanations emerged.

One, more than men, women founders and their presentations are subject to challenges and pushback. For example, more women report being asked during their presentations to establish that they understand basic technical knowledge. And often, investors simply presume that the women founders don’t have that knowledge. One woman who cofounded a business with a male partner told us, “When I pitch with him, they always assume he knows the technology, so they ask him all the technical questions.” We heard that when they are making their pitches, women founders also hesitate to respond directly to criticism. If a potential funder makes negative comments about aspects of a woman’s pitch, rather than disagree with the investor and argue her case, she is more likely than a man to accept it as legitimate feedback. “Most guys will come back at you in those situations,” an investor said. “They’ll say, ‘You’re wrong and here’s why.’”

Two, male founders are more likely to make bold projections and assumptions in their pitches. One investor told us, “Men often overpitch and oversell.” Women, by contrast, are generally more conservative in their projections and may simply be asking for less than men.

Three, many male investors have little familiarity with the products and services that women-founded businesses market to other women. According to Crunchbase, which tracks VC funding, 92% of partners at the biggest VC firms in the US are men. “In general, women often come up with ideas that they have experience with,” one investor said. “That’s less true with men.” Many of the female interviewees told us that their offerings—in categories such as childcare or beauty—had been created on the basis of personal experience and that they had struggled to get male investors to understand the need or see the potential value of their ideas. One founder told us that this lack of understanding shows up also in terms of social class when entrepreneurs pitch products for people at socioeconomic levels significantly lower than that of the typical angel or VC investor.

Implications for Change

On the basis of our findings, we have recommendations for three key stakeholder groups.

VC Firms and Other Investors. The people who write the checks have the greatest power to make change. Accordingly, VC firms and other investors need to be aware of the structural biases built into funding decisions. For example, they should seek to avoid the affinity bias that spurs them to invest in people and products that are familiar to them. They should also look for realistic projections in pitches. Most VC funds amass the bulk of their returns from a tiny subset of deals. Generally, VC firms are willing to accept losing money on the vast majority of their investments, as long as they hit one or two home runs. Mindful of this goal, VC investors search for what they perceive to be the boldest projections—the kind that men are more likely to pitch. It’s an understandable approach, but they should look for entrepreneurs who are grounding their business plans in realistic projections.

And it is critically important that they include women in investment decisions. The male-dominated culture of many VC firms and institutional investors is well documented. Bringing more women into these organizations could mean more creative and unconventional problem solving and could help broaden the lens of potential investments.

Current market forces make women-owned companies very promising opportunities.

Most important, investors should understand that current market forces make women-owned companies very promising opportunities. The lack of funding means that there is less competition for women-backed companies, and those companies, on average, perform better than those with all male founders.

Startup Accelerators. Accelerators and other organizations that promote startups also have a significant role to play in closing the investment gap. They must start by making sure that they have a balanced slate of applicants, and to do this, they must actively recruit promising women entrepreneurs. Additionally, accelerators should ensure that they have sufficient numbers of women who are experts across industries and can act as role models and mentors.

Furthermore, accelerators should coach female entrepreneurs on the realities of the market. For example, MassChallenge’s Women Founders Network initiative provides tailored resources and opportunities to support women entrepreneurs during the four-month MassChallenge program. Accelerators should work to connect women founders to the external resources—such as women-led, startup-friendly investors, incubators, partnerships, and networking opportunities—that can help them grow their businesses.

Over the long term, accelerators are uniquely positioned to create positive change. They can bring together a community of startups, women-friendly investors, and other resources—both in person and online—to build a case for change. Accelerators can share aggregate data on successful women-led businesses and become vocal advocates to the investment community while cultivating a strong network of women-friendly VC firms that their startups can tap into.

Women Entrepreneurs. The current system of startup funding puts women entrepreneurs at a clear disadvantage, but in the short term, the reality is that women entrepreneurs must work within the flawed system even as they lobby to improve it. To that end, they can use the results of our findings as market intelligence that can help them reshape their approach. To prepare their formal pitches, they should seek out coaches—ideally, with VC experience—who will assess practice runs and provide feedback. During actual pitches, they should ask for bigger investments, ask more frequently, and avoid underselling their companies. There’s no need to boast, but they do need to focus on and emphasize the positives. Armed with objective data, they should be prepared to deflect and defend against potential backers’ unwarranted criticisms.

In addition, women entrepreneurs and investors should be aware of which VC firms are led by women or have a strong record of investing in women. Those firms should not be the only options, but they should be priorities. For example, a female-led VC firm called Rethink Impact invests in companies with gender-diverse leadership teams that use technology to generate social impact. With $112 million in capital, Rethink is the largest US-based impact VC firm to apply a gender lens to investments. By late 2017, it had invested in more than a dozen companies, to which it provides coaching and guidance as well as money.

In addition, nearly 50 funds invest primarily—or exclusively—in women-owned companies, and according to the Wharton Social Impact Initiative, these funds are capitalized at more than $1 billion.

Jenny Abramson, Rethink Impact’s founder and managing partner, says, “Twenty years ago, female founders got a higher percentage of VC dollars than they do today. This is surprising when you consider the fact that data now shows that companies with gender-diverse management teams perform better financially. Our team believes that the next generation of extraordinary companies will find success through their diversity, coupled with a relentless pursuit of mission, for the benefit of all communities.”

The investment gap is real—and larger than we thought—but there are ways to help close it. By understanding the kinds of biases that put women at a disadvantage, VC firms and investors can make more objective funding decisions. Accelerators can help in terms of mentorship, resources, and networking. And women founders, while lobbying for long-term change, can operate intelligently within the current system. Eliminating the inherent unfairness in investment decisions will take time, but the measures we recommend represent a starting point—one that is long overdue.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dan Fehder, an assistant professor at the USC Marshall School of Business, for his help in analyzing the data.