Great [leaders] rejoice in adversity just as brave soldiers triumph in war. —Lucius Annaeus Seneca

A s 2019 begins, there is increasing concern about the health of the global economy. Leading indicators have weakened; economists and policymakers generally expect growth to slow; the stock market has been volatile; and geopolitical risks are multiplying. It seems prudent for business leaders to prepare for the next downturn—but they should remind themselves that adversity is an opportunity to gain competitive advantage.

Historically, companies have tended to underestimate the urgency, scale, and breadth of responses necessary to cope with and thrive in a downturn. Furthermore, the character and impact of the next downturn will likely be very distinct from prior ones—not only owing to new macroeconomic conditions, but also because today’s business environment is very different. For leaders seeking to prepare their companies for what is ahead, we offer ten actions to survive and thrive in the next downturn.

The Challenges and Opportunities of the Next Downturn

The predominant view is that the global economy is likely to experience a downturn but not a recession. Many advanced economies are at or beyond their cyclical peaks, and economic policy is becoming less supportive, pointing toward slowing growth but not a deeper recession. There are, however, downward risks to this outlook: getting economic policies right to engineer a “soft landing” has historically proven tricky, and several other political and economic risks lurk in the shadows. In such a climate, it is prudent for business leaders to prepare for a range of potential circumstances.

How do economic downturns affect businesses in aggregate? In studying more than 5,000 US companies across the last five downturns, we found that the average company saw revenue decline by 1% annually during the downturn, compared with 8% annual growth over the three prior years. Similarly, profit margins and total shareholder return also declined for the majority of companies.

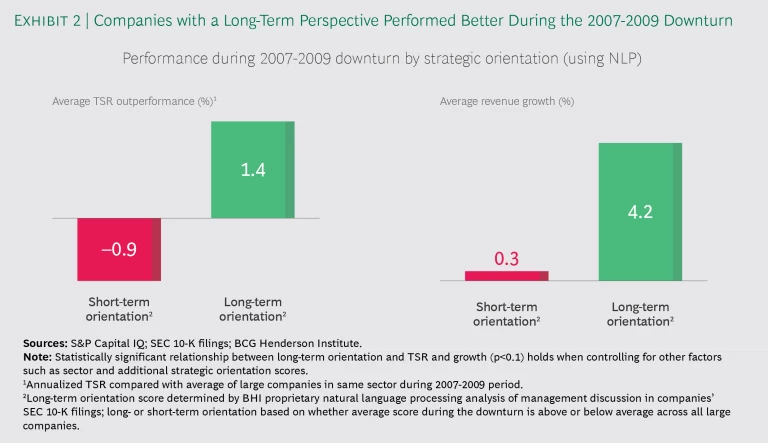

Companies’ reactions to downturns have often been defensive, delayed, and insufficient. For example, according to a BCG survey of 439 global companies, companies prioritized short-term actions over longer-term initiatives during the downturn of 2007 to 2009. They also tended to act reactively rather than proactively—waiting until their business was directly affected by the downturn before taking mitigating actions—and were reluctant to take bold steps to protect against the downsides or take advantage of the eventual recovery.

Companies’ reactions to downturns have often been defensive, delayed, and insufficient.

But downturns also present opportunities—and to realize them, companies must go beyond a defensive stance . Competitive volatility increases during downturns (for example, the rate at which businesses jump into or fall out of the Fortune 100 each year rises by 50%), reflecting an opportunity to use the downturn to your competitive advantage. Investment opportunities, including mergers and acquisitions, generally become cheaper. And some companies use the opportunity to unleash major internal change. For example, American Express was severely threatened in the 2008 financial crisis by rising default rates and falling consumer demand. After cutting costs and divesting noncore businesses to stay viable through the downturn, the company refocused on new partnerships and embraced digital technology. Its stock price has risen by more than 1,000% in the decade since.

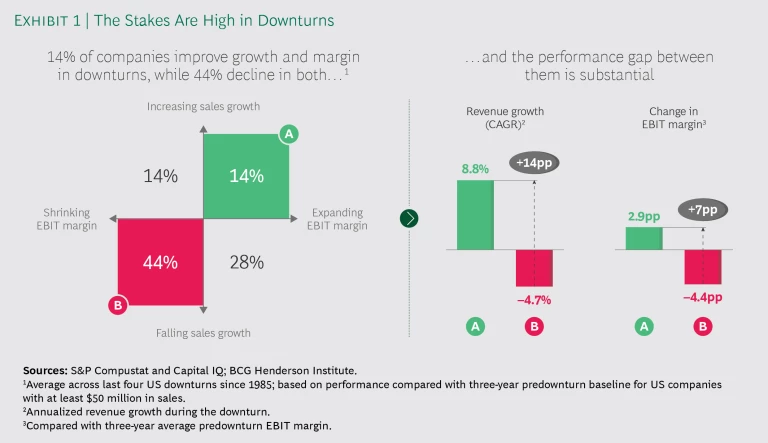

The competitive stakes in downturns are high. In the last four downturns, an average of 14% of companies increased both their sales growth rate and EBIT margin despite the challenging circumstances. During downturns, those companies grew revenue by 14 percentage points more and improved their EBIT margin by 7 points more than the 44% of companies that declined in both metrics. (See Exhibit 1.)

When the next downturn comes, how can your company be one of the few that come out stronger?

How to Take Advantage of the Next Downturn

The impact of the next downturn—and therefore what it takes to win—will naturally vary by industry and company. For example, slowing economic momentum tends to have the strongest impact on industrial goods producers, while consumer goods companies are generally less affected (and often not until later stages, when the downturn hits employment).

However, the evidence reveals some general rules that apply more broadly—giving leaders a starting point to tailor plans for their own companies. Our analysis of impact patterns and success factors in downturns builds on our empirical research on large-scale change , identifying ten ways leaders can take advantage of the next downturn.

1. Prepare for the next downturn, not past ones. Nearly a decade has passed since the last significant global downturn, and the business environment has changed dramatically since then. Some advice for weathering downturns is evergreen, but companies need to tailor their strategies to the unique aspects of today’s context.

First, the economic environment is different than it was in 2008. The most probable scenarios point to a less severe downturn; meanwhile, corporate profits are strong and cash on hand is at historically high levels. However, the rewards are increasingly earned by a smaller fraction of companies that are achieving breakaway valuations and profits. Therefore, there will be more opportunities for offensive moves but also more heterogeneity across firms in their optimal strategies and responses. For many fundamentally healthy companies, the constraint to successfully navigating a downturn may be not cash, but the wisdom to invest it against the right opportunities.

Some advice for weathering downturns is evergreen, but companies need to tailor their strategies to the unique aspects of today’s context.

Second, technological change and new competitors are rapidly reshaping industries. This has already caused competitive volatility to rise: though only one in three companies successfully navigates disruptive shifts , those that do often emerge stronger than before. The next economic downturn will likely increase the potential risks and rewards even more—but it will still be only one dimension of disruption among several. Therefore, companies will need to continue pursuing their long-term digital agenda to keep up with the accelerating pace of technology.

Finally, the political and social environment is less stable. With interest rates already low and public debt levels historically high in most major economies—and with polarization causing political gridlock—governments will have less capacity to respond to the next downturn. Increased social scrutiny will put businesses’ actions under a stronger microscope. And an economic downturn may further inflame political and social tensions. Therefore, leaders need to ensure that their businesses create social as well as economic value , and play a proactive role in shaping key social and political issues , to keep the game of business going.

2. Anticipate a wide range of scenarios. Economic forecasting is known to be very imprecise. The range of realistic scenarios is especially wide today, reflecting several sources of uncertainty that are increasingly affecting the global economy—including trade tensions, political shocks, and the dynamism of complex and interconnected financial markets. In circumstances where many plausible outcomes exist, resilience against a range of scenarios is more important than a single point forecast and plan.

Economic scenarios can be prepared around a baseline projection. Then, for each of those scenarios, determine the specific impacts on your industry and company. Through this exercise, you can stress-test your plans and measure if your company is robust to different outcomes—allowing you to identify the biggest potential risks and create rapid-response options where necessary.

Similarly, because of the unpredictable nature of competition within many industries, scenario-based approaches are also valuable tools to identify and guard against the risk of disruption. The true range of possible outcomes is often wider than you may think. Accordingly, you need to stretch your counterfactual thinking, your ability to envision “what could be”—for example, by using strategy games to widen the scope of competitive scenarios and identify overlooked vulnerabilities. With a wider view of the possibilities, you can assess your exposure to disruption, taking actions to increase resilience as necessary.

3. Act early. Many companies may understandably be reluctant to take major actions until they see clear evidence that they are affected by economic headwinds. However, the history of companies’ responses to downturns shows that the outperformers tend to anticipate the impact and make the first moves, such as reducing their cost base.

Outperformers tend to anticipate the impact of a downturn and make the first moves.

Beyond survival-focused defensive actions like cost cutting, companies are also well-advised to act preemptively when making the fundamental changes that will enable them to thrive in the long run. Our research shows that the most important observable success factor in corporate transformation is how early the program was initiated . To recognize threats preemptively, leaders need to pay attention to early warning signals of disruption—whether in the macro economy or from direct or indirect competitors. And they need to instill a sense of urgency within their organizations to ensure the necessary actions are taken before major financial or competitive deterioration.

4. De-average reactions across your portfolio. In harsh environments that threaten the viability of your business, such as an economic downturn, companies need to economize resources by cutting costs and preserving capital in order to survive and grow. But these actions should not necessarily be taken indiscriminately across the business—leaders should also have an eye on renewal , understanding what their future growth engines will be and de-averaging accordingly. In other words, during the downturn, companies should protect the budgets of businesses or locations that still have attractive growth opportunities, while making the necessary cuts elsewhere. In many cases, they will need to both rationalize and reinvest within the same business.

De-averaging your response to a downturn has obvious benefits, yet many companies still find it hard to do in the heat of a crisis. For example, according to BCG’s 2009 survey, less than one-third of the companies that reduced costs in some parts of the business also added employees or capacity in another area. To successfully de-average strategy in various parts of the business, you need to develop strategic —for example, by structurally separating business units that require different approaches to strategy and implementation.

5. Adopt a long-term, competitive perspective. By threatening short-term performance and survival, downturns present an operational challenge. At the same time, however, they present competitive opportunities—which some companies will seize to emerge stronger. All companies must attend to short-term concerns to ensure viability, but those that are able also to focus on the long run have the most success.

6. Use the downturn to accelerate large-scale change. Even when companies recognize the disruptive threats and the need to transform, they often underestimate the full scope of changes that are necessary. Downturns can shine a spotlight on the long-term viability of the business—which farsighted leaders can leverage to ensure the change effort is sufficiently ambitious. This is indeed likely to pay off in the long run: our research shows that transformation programs with larger investment are more likely to succeed .

For example, Apple released its first iPod in 2001—the same year the US economy experienced a recession, contributing to a 33% drop in the company’s total revenue. Still, Apple continued to transform its product portfolio, investing in innovation and increasing R&D spending by double digits. As a result, the company launched the iTunes music store in 2003 and new iPod models in 2004, sparking an era of high growth .

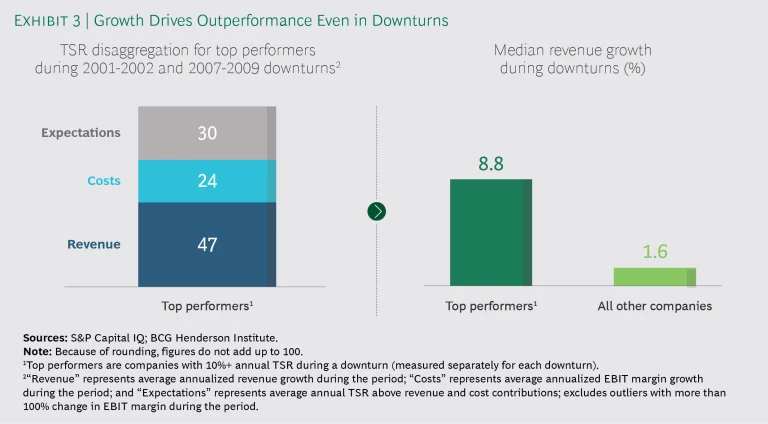

7. Invest in growth engines. Defensive actions may be necessary for some companies to survive the downturn—but to thrive, leaders need also to consider the top line. In the last two downturns, the most successful companies did indeed pursue efficiencies, improving their profit margins.

Furthermore, growth during a downturn appears to have competitive benefits that continue to pay off: the companies that grew more during downturns also achieved higher post-downturn growth. To successfully grow over the long term, companies need to invest in R&D and innovation, and maintain a balanced “portfolio of bets” across multiple timescales. A downturn should not undermine the capacity for long-term growth.

8. Articulate a compelling investor story. After revenue growth, the next-largest driver of TSR in recent downturns was investors’ expectations—which also had a greater impact than cost reductions. And with activist campaigns becoming more frequent and targeting even the largest companies, the risk to leaders of not managing investors’ expectations is larger than ever. Because downturns on average reduce TSR and profitability—two conditions that increase the threat of activism—leaders will need to make sure they maintain credibility. This involves “thinking like an activist” : optimizing financial policies and current performance, while also building strong relationships with major investors and ensuring that the long-term strategy is understood.

Formalized, publicly announced transformation programs are often one component of a compelling story. Internally, such programs can build support for change throughout the organization. But our research also shows that they help build credibility with investors: underperforming companies that announced a formal transformation program were more likely to see a short-run boost in investor expectations, as well as a long-run improvement in financial performance.

9. Opportunistically pursue M&A. “The time to buy is when there’s blood in the streets,” said Baron Rothschild after the Battle of Waterloo. M&A has become a larger part of many companies’ strategy, with deal volumes trending upward for several years . Overall activity fell in the last two downturns, which means there will likely be cheaper buying opportunities for the select companies that have the will to pursue it—and have maintained strong enough cash positions to afford it.

However, the set of available targets they face will include more poor-performing companies in need of a turnaround, rather than thriving companies that can give the buyer an immediate boost. Our research of nearly 3,000 turnaround M&A deals reveals several important empirical lessons for choosing these deals and making them work. The most successful turnaround deals involved companies of the same sector and with similar cultures, more ambitious synergy targets, and a rapidly initiated turnaround program after the deal closed.

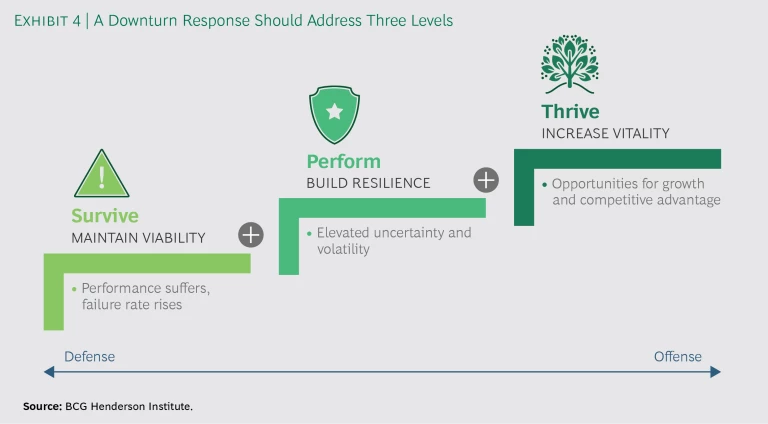

10. Structure your downturn response across three levels. To prepare for a downturn, leaders should consider their response across three levels ranging from defensive to offensive moves. The focus necessary on each level may depend on the company’s specific situation, but those that come out of a downturn strongest will have addressed all three in their preparation and response. (See Exhibit 4.)

- Maintaining Viability. Downturns present an increased risk of failure, and staying alive is already more challenging for companies of all sizes and in all sectors. Companies need to make sure their business remains viable in the event of a downturn—for example, by reducing inventory and managing receivables and payables more aggressively to protect cash flow; streamlining the core business to increase efficiency and flexibility; and reassessing the long-term viability of businesses, divesting or closing some if necessary.

- Building Resilience. The next downturn is likely to be accompanied by very high uncertainty along a number of dimensions. In order to perform well in unpredictable conditions, leaders must build resilience in their businesses—for example, by keeping financial buffers to be able to respond to unanticipated opportunities or threats; shrinking planning cycles to increase adaptiveness; and hiring talent with a range of backgrounds and laying an inclusive foundation to promote a diversity of ideas.

- Increasing Vitality. “[Defense] should be used only so long as weakness compels, and be abandoned as soon as we are strong enough to pursue a positive object,” said military theorist Carl von Clausewitz. The companies that outperform in downturns generally seek growth rather than playing only defense. However, growth is especially difficult to achieve today. Companies need to increase their vitality, the ability to explore new options and grow sustainably in the long run —for example, by assessing competitors’ vulnerability and capitalizing on weaknesses by investing in new capacity or M&A; implementing metrics to measure the company’s capacity for future growth; and adopting a forward-looking, long-term agenda to win in the 2020s .

The next downturn will test many companies, but it will greatly advantage the few that adopt a strategic approach. By maintaining a long-term strategic perspective, investing selectively, and pursuing transformative change, leaders can help their companies emerge from the next downturn competitively stronger than they entered it.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit

Featured Insights

.