The aerospace and defense (A&D) industry has created significant value for shareholders over the past decade, but management teams must be proactive if they expect to live up to strong expectations and defend their future. For the ten years through 2018, the industry generated an average annual total shareholder return (TSR) of 13.8%.

For the first time in this series of value creation reports, the industry’s TSR performance fell below that of the S&P 500.

There are clear reasons for that strong performance, including growing demand for commercial air travel and the modernization of national defense fleets. A&D, like all other industries, also benefited from fortuitous timing: ten years ago, when we initiated our analysis, the global economy was poised to recover from the financial crisis. Despite this good news, A&D companies face strong expectations from investors that their value creation will continue—in the form of valuation multiples, which have never been higher. That puts pressure on management teams to execute, and, in particular, to hit strong growth targets.

What can management teams do in the face of these expectations? First, they must anticipate and prepare for macroeconomic trends that could disrupt their growth agenda. Second, if growth does begin to slow, revisiting and revising financial policies (such as increasing dividends) could help them manage investors’ expectations while supporting a higher multiple. Third, proactively using highly valued stock to make acquisitions may be a way to win in higher-growth segments of the future. Finally, they should consider shifting their investor mix by altering their messaging and aggressively seeking investors that align with long-term expectations.

A Strong Decade of Value Creation

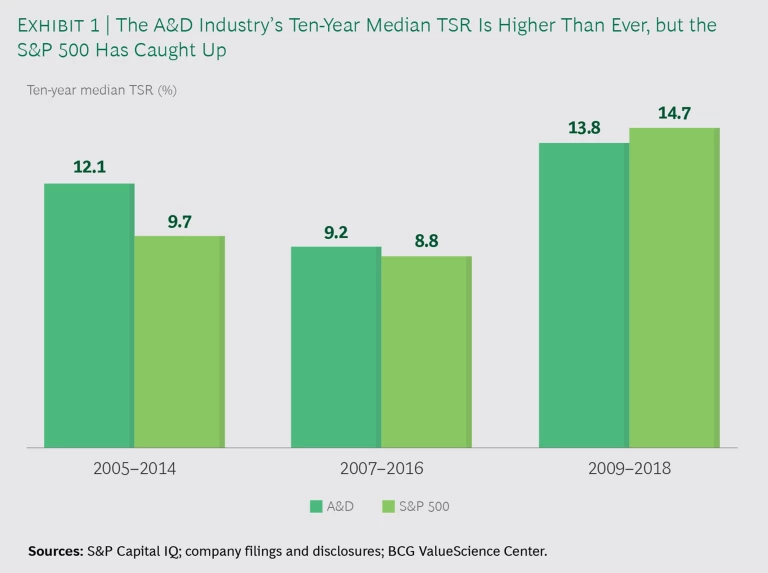

To understand the key drivers of TSR, as well as how to proceed, management teams need to step back and review the overall market. As a whole, A&D remains a lucrative industry for shareholders. The 13.8% ten-year average annual TSR for the 63 A&D companies in our sample is higher than it was in the ten-year periods ending in 2016 (when the industry returned 9.2%) and 2014 (12.1%).

This performance is strong even compared with a historically long-run bull market in US equities. Last year, BCG evaluated the TSR of 2,425 companies and found that, on the basis of five-year TSR, A&D ranked tenth among 33 industry segments.

That TSR performance reflects strong industry trends that are likely to continue. On the commercial-aviation side, demand for air travel continues to grow, driven in large part by the rise of living standards in developing markets. On the defense side, fleet modernization programs and sustainment imperatives are leading to continued spending.

Yet, while the industry’s TSR performance was strong in absolute terms, it was less impressive in relative terms. In previous analyses, the A&D industry outperformed the overall market, sometimes by significant margins. This year, it fell short, lagging behind the S&P 500 by 90 basis points per year. The biggest reason for the difference is that other industries have caught up in terms of performance and expectations, particularly during the historic ten-year bull market in the US. (See Exhibit 1.)

A Tale of Two Segments: Defense Outperforms

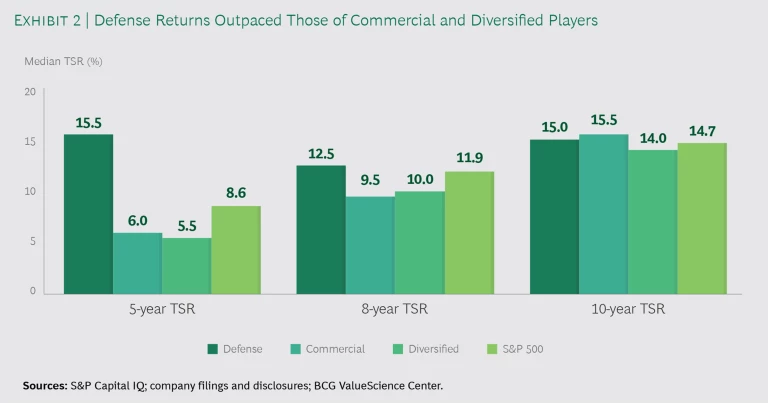

Defense, commercial, and diversified players all returned average annual TSRs of about 15% over the full ten years of our analysis, but a look at more recent trends reveals a tale of two segments. For the five- and eight-year periods through 2018, defense companies significantly outperformed not only commercial and diversified players but also the S&P 500. By contrast, commercial and diversified firms saw much lower TSRs, especially in the short term. (See Exhibit 2.) One mitigating factor is commercial OEMs’ substantial backlog of orders, which will continue to generate cash in the near future.

There are several reasons why defense companies have been able to deliver such strong returns. First, the military procurement cycle is less susceptible to market forces, which can swing shareholder returns of commercial and diversified firms. Moreover, defense budgets continue to grow—particularly in the US following the budget sequestration—and commercial firms haven’t had a comparable growth driver. Finally, there is increased focus on sustainment and long-run support for aging fleets, particularly in the US Air Force and US Navy, while commercial players have tended to refresh fleets fast enough to avoid costly life extensions.

This doesn’t mean that defense players can relax. Changes in the political climate, the likelihood of federal budget gridlock, and shifts in military priorities can still affect defense budgets and planning. Defense players should engage in scenario exercises, preparing responses to any plausible impact to their top line by reducing costs, changing their pricing strategies, remaining opportunistic about growth opportunities (both organic and through acquisition), and launching broader transformations.

The Benefit—and Burden—of High Valuation Multiples

A deeper dive into the findings on TSR shows the underlying contributors to value creation, giving management teams a key advantage when prioritizing their efforts. Historically, TSR in the A&D industry—and most other industries—has been driven by sales growth. For example, our 2017 analysis showed that sales growth contributed more than half of the TSR for top-quartile A&D performers.

In our current analysis, sales growth is still the most important driver of TSR, but by a smaller margin. Revenue growth contributes most (roughly one-third) of TSR for top performers, but we have observed a significant expansion in valuation multiples, which contributed 28% (compared with 13% in 2017) of the total value creation for top performers. This multiple expansion suggests that investors have elevated expectations for the sector.

In our current analysis, sales growth is still the most important driver of TSR, but by a smaller margin.

Moreover, the underlying factors that affect OEMs’ valuation multiples are different from those that affect suppliers’ multiples. Drilling down one more level, we looked at the key factors that affect valuation multiples for both groups.

- For OEMs, about 60% of the valuation multiple stems from a company’s EBIT margin, dividend policy, and revenue expectations (in that order). This suggests that an OEM’s multiple expansion is driven by investors’ expectations that it will generate cash as the segment grows.

- For suppliers, a similar component of the valuation multiple comes from gross margin and operating expenses. (We looked at the TSR breakdown of industrial-supply companies as a proxy for A&D tier one suppliers, because consolidation among large suppliers in the industry has made it difficult to conduct direct comparisons.) Thus, tier one suppliers can use operational excellence and margin management in areas such as strategic pricing and procurement to improve value creation.

In addition to focusing on sales and margin growth, leadership teams for OEMs as well as suppliers can be more proactive in managing investors’ expectations and the resulting multiples. One approach to consider is increasing dividends should growth slow. Our analysis shows that in addition to boosting multiples, higher dividends contribute directly to TSR.

A&D companies need to tell a clear story to the investor community—a story that appeals to their desired type of investor—and deliver against this vision.

A second approach to proactive management of expectations is to shift the investor mix. Firms could change the narrative they communicate to shareholders and recruit investors that are better aligned with sustainable growth rates. For example, companies that currently have a large proportion of growth investors might consider diversifying their investor mix to include growth-at-a-reasonable-price and value-oriented investors.

Changing OEM and Supplier Dynamics

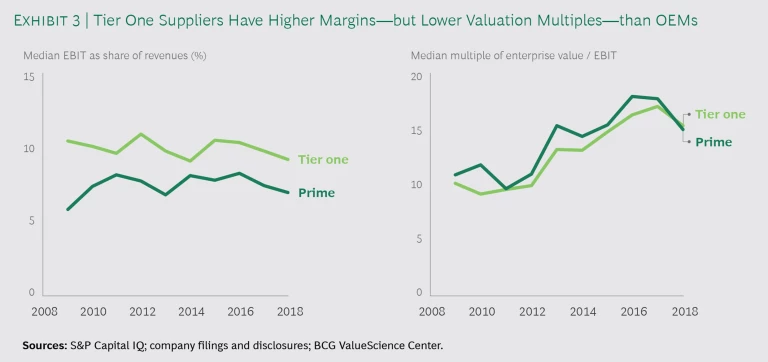

Another aspect of the relationship between OEMs and tier one suppliers is their changing ability to create value. Historically, suppliers have generated higher EBIT margins, while OEMs enjoyed slightly higher valuation multiples. (See Exhibit 3.)

It is worth noting that on a market-cap-weighted basis, OEMs generated higher ten-year returns than tier one suppliers. For example, if, in 2008, $10,000 had been invested in an index fund consisting of the OEMs in our peer group, it would be worth $64,724 today (a compound annual growth rate of 20.5%). The same investment in an index fund of tier one suppliers would be worth $45,057 (a CAGR of 16.2%).

That said, dynamics between OEMs and suppliers are always evolving. OEMs have continued to aggressively develop internal sources for key components, in some cases simply cutting suppliers out of the value chain. For example, Boeing decided to integrate vertically by developing an in-house avionics business unit in 2017. In other cases, OEMs have pushed suppliers for better terms, offering orders to a smaller set of suppliers and giving them higher order volume in exchange for better prices, faster production, and fewer quality issues. OEMs have also expanded into the lucrative aftermarket segment for parts and services—for example, Airbus’s acquisition of Satair and Boeing’s acquisition of KLX Aerospace Solutions.

On the supplier side, consolidation in the industry has continued. Since our most recent A&D Value Creators publication in 2017 , there have been several mergers, including United Technologies’ acquisition of Rockwell Collins for $30 billion and Safran’s acquisition of Zodiac Aerospace for $9 billion. This consolidation creates opportunities for tier ones to reorganize and improve their operational effectiveness, potentially becoming one-stop shops for OEMs.

Management teams on both sides can still take advantage of strategic acquisitions to create value. As high multiples and share prices give them the means for making acquisitions, OEMs and tier one suppliers alike should actively consider targets in key adjacencies to win in future growth businesses.

How Leadership Teams Should Respond

The TSR findings point to specific priorities for A&D leadership teams that aim to achieve superior value creation.

First, all companies need to be prepared for the breadth of plausible future scenarios. Both defense and commercial players have enjoyed strong tailwinds over the past decade, but the heavier influence of multiples means that growing political, trade, and economic uncertainty may lead to larger swings in TSR. Companies should have plans for responding and should be prepared with the necessary resources in place.

Second, growth is critical, and BCG research shows that shareholders reward growth through acquisition . Our analysis shows that active dealmakers in A&D—companies that have spent on average more than $1 billion on M&A per year over the past five years—have higher five-year annual TSRs (14%) than those that stayed on the sidelines and invested less than $25 million per year during that period (4%). The recently announced merger of Raytheon and United Technologies is a good example of companies looking to create value through scale-driven M&A.

Similarly, vertical integration—through acquisition or organic expansion—is complex but could offer opportunities for OEMs and tier ones to minimize production risk and capture the aftermarket. Our analysis, this year and in the past, has demonstrated that being “asset light” does not necessarily correlate with TSR. Thus, in-sourcing the manufacture of selected products can—if managed well—be lucrative.

In addition, the increased contribution of expanding valuation multiples to TSR shows that A&D companies need to tell a clear story to the investor community—a story that appeals to their desired type of investor—and deliver against this vision. One approach is to focus on the aftermarket, a traditionally high-margin business. As noted above, some OEMs and tier one suppliers are already expanding into the aftermarket segment. This growing competition and integration will likely drive increased complexity in negotiations associated with aftermarket access and the ownership of intellectual property.

If growth does slow, increasing dividends could help mitigate the impact on value creation. Our analysis shows that dividends play a major role in determining multiples, giving management a tool for potentially offsetting declines in other areas.

Finally, digital is not just another option for boosting revenues and enhancing margins. It is becoming an imperative. Virtually all companies are looking at ways to use technology to grow revenues and cut costs. For example, by investing in data and analytics to improve the accuracy of their measurements and performance predictions for maintenance, repair, and overhaul, organizations can enhance performance and reliability and reduce downtime for their customers. On the defense side, data generated from aircraft can be used for predictive maintenance to improve the fleet’s mission readiness. The Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightening II can even use its sensors and onboard data library to synthesize data and assess threats to the pilot in real time.

Still, in many ways, the digital ecosystem in aerospace and defense remains in its infancy, as OEMs, airlines, repair facilities, and tier ones test various digital strategies. Even with heightening interest in the application of advanced analytics and digital transformation, the business case for such investments is still hard to define. Successful companies will design a digital strategy, remaining aware of the evolving ecosystem among market participants and focusing strictly on the highest-return opportunities.

The A&D industry’s strong value creation performance over the past decade has led to rising expectations among investors. That’s a good problem, but it will challenge leadership teams of OEMs as well as suppliers. To win, companies will need to understand the key factors that affect value creation and then craft their strategies accordingly.