A seismic shift is occurring in consumer packaged goods (CPG)—but manufacturers are not keeping pace.

Online sales grew rapidly from 2013 to 2018—19% annually versus the anemic 1% growth rate of in-store sales. All told, e-commerce now accounts for 40% of the growth in CPG retail sales. The problem: large CPG companies continue to lag in e-commerce, posting weaker performance in the online arena than they do in the offline.

This lagging performance comes at an increasing cost. Large CPG companies, on average, have online market shares that are at least 5 to 10 percentage points below the shares they enjoy in the brick-and-mortar world. This translates into hundreds of millions of dollars in lost sales opportunities. In addition, CPG companies (and retailers) have struggled to develop online categories in which a high percentage of sales are impulse or unplanned purchases—including confectionery, where almost half of sales are unplanned.

Given the stakes, CPG companies need to shift gears dramatically. We have identified four steps that companies must take in order to make up lost ground in e-commerce. First, they need to understand the diverse retail environments that currently exist in e-commerce and develop strategies to compete in each one. Second, they need to focus on driving online traffic to their products and upping the rate at which they convert online browsers into actual buyers. Third, they must maximize availability by building an online supply chain that is robust and reliable in order to prevent stock-outs. Fourth, they should ensure that their organization has the analytical capabilities and the culture of experimentation required to succeed.

CPG companies need to shift gears dramatically and take four steps to make up lost ground in e-commerce.

As online sales across many CPG categories accelerate, investing to catch up—including in search rankings, traffic, reviews, and market share—becomes increasingly expensive. Ultimately, companies that fail to recognize the urgency to adapt will see weaker sales growth, market share erosion, and a diminished brand.

The E-Commerce Challenge for CPG Companies

CPG companies have generally been slow to devote significant resources to e-commerce for several reasons. Among them: online sales have not taken off as quickly in CPG as they have in other categories, such as books and consumer electronics. According to Nielsen, the online channel accounts for less than 10% of overall CPG sales; the penetration varies by product category. Some 13% of revenues in the pet care category, for example, comes from online sources, while the share from meat and dairy is just about 2%. Given the relatively slow takeoff in most categories, companies have simply not been forced to adapt as quickly in the CPG space as they have in some other sectors.

In addition, slow growth in the CPG industry in general has created financial pressure on companies, including the need to cut costs. As a result, CPG players have not had the financial flexibility to direct major energy and resources to the small—but fast growing—e-commerce channel.

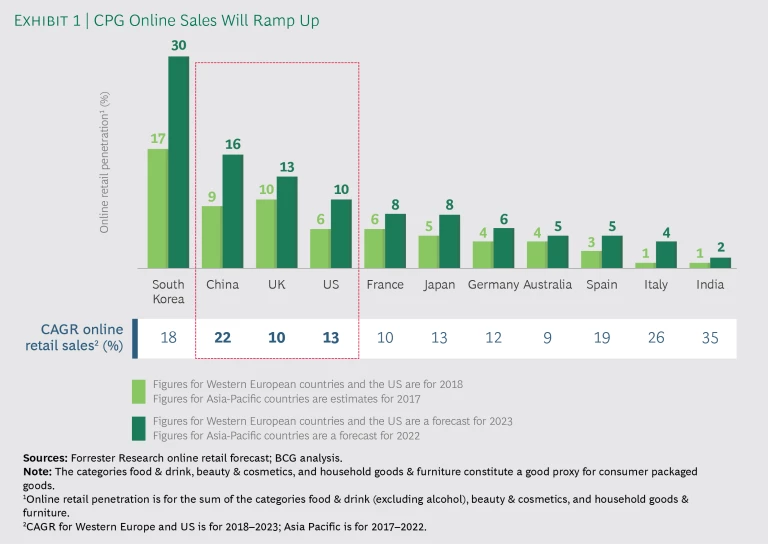

Around the world, however, the share of sales coming from online channels is expanding rapidly. Already e-commerce represents 23% of total retail sales in China, where adoption has occurred along a steeper curve. While online sales for food and drink, beauty and cosmetics, and household goods and furniture—a collection of categories that is a good proxy for CPG—are just 9% of the total in China, that figure is expected to grow to 16% by 2022. And the online share for those categories in some countries, including the US (currently at 6%) and the UK (10%), is also expected to take off over the next few years. (See Exhibit 1.)

The acceleration of online retail sales comes as CPG companies face big challenges within their traditional brick-and-mortar channels. Multiple trends have contributed to a slowdown in industry growth. For example, consumers are dining out more frequently and are moving away from packaged foods to purchasing fresh and prepared options when they do dine in. At the same time, small—and frequently digitally savvy—brands grabbed about $15 billion in sales from their larger counterparts from 2012 to 2017. (See “How Big Consumer Companies Can Fight Back,” BCG article, September 2017).

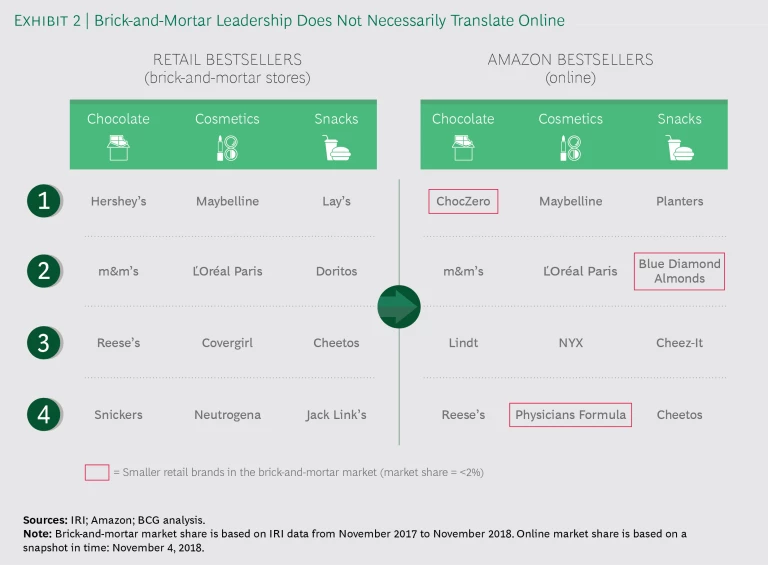

Amid those pressures, many large CPG companies continue to lag in e-commerce strategies and capabilities, falling behind in the fastest-growing channel. While most have made investments in e-commerce teams and capabilities over the past few years, those investments have not been sufficient to meet the challenge, and these large companies continue to lag smaller rivals when it comes to execution. In categories such as chocolate, cosmetics, and snacks, for example, big companies continue to enjoy relatively high market shares in the brick-and-mortar world, while a number of smaller players have carved out significant online share. (See Exhibit 2.) Hershey’s, for example, is the number-one chocolate brand in the brick-and-mortar retail world, with 12.6% market share. But on Amazon.com, the number-one chocolate brand in November of 2018 was ChocZero, which holds less than 0.5% market share in brick-and-mortar retail stores.

Four Steps to Winning Online

Big CPG companies can reverse their slow start in e-commerce. But doing so will require focus and execution in four key areas.

Match the strategy to the e-commerce retail environment. Today, many companies’ e-commerce strategies focus on selling products through Amazon. No doubt, Amazon remains the leader, accounting for an impressive 44% of all US e-commerce sales in 2017 (about 4% of total retail sales) according to Edge by Ascential. But there are many other e-commerce retail sites—including those with so-called click-and-collect models, where consumers purchase goods online and then pick them up in the store—on which CPG companies must also capture share to maximize total growth. CPG companies, therefore, need to develop strategies for competing across the entire channel. To succeed in that effort, companies must understand the specific characteristics of those online retail environments, including the shopper missions—for example, stocking up on bulk items versus buying fresh foods for the week’s meals—to which those retailers cater.

CPG companies need to capture share on many other e-commerce sites in addition to Amazon, including those with click-and-collect models.

The Amazon Marketplace model, for instance, offers a seemingly limitless assortment of items, and consumers often search for and buy only one or a few items per transaction. Other online retailers—including Fresh Direct, Kroger, and AmazonFresh—have online models that more closely mirror a supermarket experience, allowing consumers to purchase a virtual basket of items (including fresh foods as well as nonperishables) from a limited assortment. In these models, the shipping costs of any individual item are defrayed by the larger number of items in the basket. Still other online models, such as the ones used by Costco and Boxed Wholesale, focus on consumers or small businesses that want to replenish their pantries with bulk items. On those sites, assortments are more limited than those offered in a full supermarket, but pack sizes are larger, and the volume discounts are greater. There are also online players that cater specifically to consumers who are looking for gifts or hard-to-find items or who are making impulse purchases.

To meet the demands of these different retail environments, companies must offer the right assortment of products. Doing so hinges on two key factors:

- Variety. CPG players need to decide the kind of variety of offerings—whether, say, flavors for food products or different formulations for skin care—that is optimal for each retail site. In general, less is definitely not more in this context because consumers tend to value broad selection when shopping online. According to Edge by Ascential, for certain categories such as chocolate and cosmetics, the likelihood of a company having a brand in the top 20 in terms of search results is strongly correlated with the number of products that the company offers. In addition, enhancing the variety of products offered can lead to an improvement in revenues of 5% to 15%.

- Packaging and Pricing. CPG companies may also need to develop new pack sizes and price points to meet consumer demand, which can differ significantly across online retailers. For instance, larger pack sizes can encourage stock-up behavior and also help push the transaction up to $10 to $15—the point at which the shipping economics often improve for any given individual item. CPG players can also design specific online pack sizes and prices to avoid problematic, visible price differentials among channels. Finally, most CPG packaging is created to look good on a retail shelf—not to be easy and convenient for online shoppers to open and use. CPG players have an opportunity to develop lighter packages that are easier to open.

Drive traffic and conversion. It is critical for companies to drive traffic to their products on retailers’ websites and encourage consumers to actually make a purchase (conversion). Traffic and conversion create a virtuous circle: consumers who buy products and then write reviews about them drive new sales as the reviews improve the search rankings and conversion rates of those products.

It is critical for companies to drive traffic to their products on retailers’ websites and encourage consumers to actually make a purchase.

- Drive traffic. The amount of traffic generated for a particular product hinges largely on where that item falls in the search rankings. Search rank performance, in turn, depends on a few factors. Companies must ensure that their product descriptions contain the most relevant and popular search terms and have healthy numbers of positive consumer reviews. Edge by Ascential has found a significant positive correlation between the number of reviews and search rank placement. In the cosmetics and chocolate categories for Walmart online in the US, for example, the correlation between the two is 0.6 and 0.7, respectively.

In addition, companies need to develop marketing and promotion strategies that drive consumers to their product. A significant factor here is precision marketing, the ability to target specific messages to likely buyers. While Walmart.com, Amazon.com, and other online platforms do not share user data with manufacturers, CPG marketers can use services, such as Amazon Advertising, to employ precision marketing tactics.

- Drive conversion. Too many retailers today have product pages with subpar images and little content that will excite shoppers and prompt them to hit the “buy now” button. Companies must create high-quality content—including compelling product descriptions, high-resolution photos, and videos that give shoppers the feel of the product. In addition, the quality of product reviews can be a decisive factor in conversion. Overall, high-quality content can drive an increase in sales of 5%, according to analysis from Edge by Ascential. At the same time, CPG manufacturers should ensure that their product ads, as well as their own websites, seamlessly direct shoppers to an online retailer where they can make a purchase. If there’s too much friction between the ad and the transaction, the sale will be lost.

Note that the approach to maximizing traffic and conversion may differ depending on the retail environment. Top-selling brands on Amazon.com, for example, often differ significantly from top sellers in brick-and-mortar stores. That highlights how distinct Amazon’s market is and how critical it is for CPG companies to understand how Amazon algorithms drive traffic.

On sites such as Walmart.com and Kroger.com, however, there is often more overlap between leading brands online and those in physical stores. Edge by Ascential has found that for certain categories, such as chocolate in the US, the correlation between the top 20 brands on Walmart.com and the top 20 brands in terms of sales in overall brick-and-mortar stores is 0.8. In contrast, the correlation between the top 20 brands on Amazon and the top 20 group in retail stores is just 0.1. The upshot: CPG companies have an opportunity to grab more share on Amazon and to leverage their existing relationships with players such as Walmart and Kroger in the brick-and-mortar channel to drive online demand at those retailers.

Ensure availability. One of the most damaging events for a company selling online is the inability to meet demand. If an item is out of stock, it can be dropped from Amazon search results, or the customer can be directed to a third-party seller. In either case, the CPG company loses the sale.

That’s why it is critical for CPG companies to adapt their supply chains to meet e-commerce demand. (See “As Grocery Goes Digital, How Should CPG Supply Chains Adapt?” BCG article, October 2017.) No doubt, this can be challenging. Large CPG companies have expansive, sophisticated supply chains designed for the brick-and-mortar world and need to address the wide variety of supply chain challenges introduced by e-commerce. Among them: SKU proliferation, the need for packaging that is well suited for e-commerce, and high service expectations from retailers such as Amazon.

Amid such complexity, companies must find ways to make their supply chains more flexible and responsive.

Adapt the organization. CPG companies need to change the function of their organizations in two fundamental ways. First, they should drive more cross-functional collaboration. Second, they need to ensure that the company has the analytical skill set and culture of experimentation required to execute and adjust their online strategies.

- Cross-Functional Collaboration. In the offline world, marketing, sales, and the supply chain often operate in functional silos. In broad terms, the marketing function drives demand through brand-building activities and investments; the sales function manages customer strategies, including merchandising and pricing and promotions; and the supply chain function manufactures the product and ensures availability on the shelf. In the online world, the distinctions are more blurred. E-commerce retailers offer media and marketing opportunities that require marketing investments. Supply capabilities have significant impact on virtual-shelf presence, search rank, and sales. And new packs may be needed to maximize demand opportunities. As a result, a well-functioning e-commerce leader and team must have seamless collaboration across functions.

- Analytical Skill Set and Culture of Experimentation. The capabilities and mindset required to win in e-commerce are distinct from the ones that worked well in the brick-and-mortar world of CPG. Historically, key success factors in traditional retail were the strong personal relationships and the trust that CPG sales teams developed with retail buyers and executives. Joint business planning was done annually, with periodic reviews of sales performance. Such connections and processes mean little in e-commerce, where online retailers rely on analytics and algorithms to make decisions, and the virtual shelf is managed in real time. As a result, CPG companies must develop teams that can analyze and improve execution tactics, including the management of out-of-stock events and promotions, on the basis of real-time data feeds. Concurrently, executives at high levels of the organization need to develop a dashboard of KPIs that can track and monitor performance in order to understand how well the company is performing and where gaps remain.

In addition, CPG leaders need to create a culture of experimentation. This should include testing and learning new tactics and working with different types of vendors and partners. People must be encouraged to try unfamiliar things—and be willing to fail. Experimentation will yield powerful lessons and allow the organization to both learn from experience and adapt its approach.

Creating Momentum

The explosive growth of e-commerce is transforming the retail world—and changing the sources of competitive advantage for CPG companies.

To survive and thrive, CPG players need to embrace the disruption. They must develop strategies that are tailored to the myriad of online retail environments in which they will compete and the models they will face. They must continuously improve traffic and conversion tactics on the basis of real-time feedback about what is working—and what is not—while making sure that the supply chain can meet e-commerce demand. And e-commerce leaders must be empowered to collaborate and draw on resources from across traditional functional silos. Most important, they need to experiment, test, and learn to adapt to changing consumer habits and developments. The companies that embrace this philosophy will emerge as winners in the quest for online market share.