AIで競争優位性を構築するには、価値を創出できるよう意思決定とオペレーションを再編成し、人間の組織能力に投資して浸透させる必要があります。どうしたらAIを組織に拡大展開できるかを考えるうえでBCGのAIに関する最近の論考などがお役に立てば幸いです。

Welcome to BCG

Unlocking the Potential of Those Who Advance the World

Article

2025年4月11日

Article

2025年4月11日

都心部はいま、再生の瞬間を迎えています。中心業務地区(CBD)は、変化する働き方、そして暮らし方に合わせて再構築されつつあります。

Article

2025年4月2日

Article

2025年4月2日

BCGは日本全国の18歳以上の消費者を対象に、消費行動の変化や物価変動に対する心理を分析する調査を継続的に実施しています。その最新の結果を紹介します。

Article

2025年1月15日

Article

2025年1月15日

1,800人以上の経営層を対象にしたBCGの調査によると、AIは2025年も引き続き、世界中のビジネスリーダーにとって最優先事項となっています。特に、AIで具体的な成果を生み出すことに焦点が当てられています。

Report

2024年12月13日

Article

2024年12月13日

「BCGカーボンニュートラル・インデックス」は、日本企業を対象に、カーボンニュートラル経営への取り組みの成熟レベルを評価する指標です。最新の調査では、サステナビリティ経営も評価対象に追加しました。

Article

2024年10月30日

Article

2024年10月30日

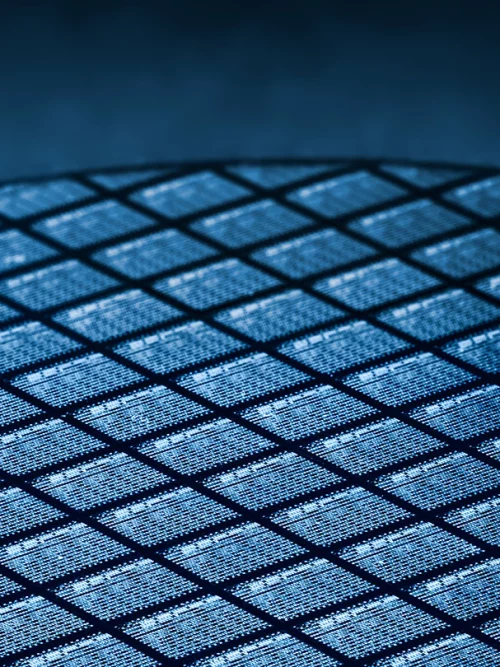

日本における半導体産業の現状を整理、分析するとともに、その発展に向けて必要な条件を探ります。

Article

2024年10月29日

Article

2024年10月29日

BCGは、サステナブルな社会の実現に関する消費者意識や購買行動の変化を理解するために定点調査を行っています。その最新の結果を紹介します。

Book

BCGが読む経営の論点2025

不確実性の高い時代、企業リーダーにとって、世界的な潮流を読み取ることは自社の戦略の方向性を定めるうえで欠かせません。本書は、今後10年先の事業環境を見据え、2025年時点で優先的に検討すべきとBCGが考える経営上の重要論点を提示しています。

最新の論考 (業界/テーマ別)

気候変動を緩和するための道筋には、パブリック、ソーシャル、民間の各セクターにわたる協働が求められます。どうしたら気候関連の真の変革を実現できるかを考えるためにBCGの最近の論考をご覧ください。

勝利をおさめるには今日のゲームをうまくやるだけでなく、次のゲームに向けて勝てる態勢を整える必要があります。勝ち抜く戦略を策定・実行するためのヒントを得るうえでBCGの論考がお役に立てば幸いです。

BCGのサービス、専門知識の紹介

ご関心のあるテーマや業界をお選びの上、サービス概要・支援事例、エキスパート、最近の論考などをご覧ください。

プリンシパル・インベスター、プライベート・エクイティ

プライベートキャピタルの急速な成長により、社会にプラスの効果を実現しつつ価値を創造する空前の機会がもたらされています。BCGは先進的投資家に対して、優位を持続する方策についてアドバイスしています。

イノベーション戦略策定・実行

イノベーションはけっして容易ではありませんが、必要です。私たちは、クライアントが長期的競争優位性を確立するための包括的なイノベーションの道筋にわたって、クライアント組織と密に協働します。

コーポレートファイナンス&ストラテジー

ビジネスのルールや競争優位性を持続するための原則が変化しています。私たちは、ペースの速い世界で企業が戦略や価値創造を再構想するお手伝いをします。

ダイバーシティ/エクイティ/インクルージョン

私たちの支援により、クライアントは世界や地域社会の多様性を十分に反映したチームを構築し、自社の事業や社会を前進させるための力を得ることができます。

トランスフォーメーション

現在のトップ企業であっても、常時進行中のトランスフォーメーションの組織能力が効果を発揮するでしょう。レジリエンスを育み、長期的な価値創造につながります。BCGはこの筋肉を鍛えるために何が必要かを理解しています。

パーパス(存在意義)

パーパスの発掘は、企業にとって見返りのある変革の道程の一部です。BCG傘下のブライトハウスは、組織がパーパスを活用して、収益性や従業員エンゲージメント、顧客満足を向上できるよう支援します。

ビジネス・レジリエンス

経営リーダーは不確実な環境に直面しています。それぞれの意思決定の影響が予想できないと感じられ、だからこそ、先を見越した、レジリエンス(回復力)や競争力が高い戦略が求められています。出発点がどこであれ、BCGがお手伝いします。

プライシング・レベニューマネジメント

BCGは、クライアントが効果的なプライシングのパワーを引き出し、収益性向上ポテンシャルを解き放つための専門知識とデータドリブンの戦略を提供します。

マーケティング・セ-ルス

顧客中心主義がカギであり、それはアナリティクス、アジャイルなプロセス、テスト・アンド・ラーンのカルチャーを通じて可能になります。BCGは、マーケティング・営業組織と協働して、それを実現します。

リスクマネジメント、コンプライアンス

BCGのリスク、コンプライアンス領域のコンサルティングでは、戦略、トランスフォーメーション、技術の各側面にわたる専門能力を通じて、クライアントの成長への取り組みをサポートします。

BCG Careers

Go Beyond with BCG

BCGの存在意義は、クライアントや社会、そしてBCGで働く社員一人一人の可能性を開花させることです。私たちと共に、あなたの可能性を大きく広げませんか。

Featured Insights

BCG’s most inspiring thought leadership on issues shaping the future of business and society

Get the latest industry insights delivered to you