If M&A is really one of the best ways to accelerate profitable growth, how come the numbers tell a somewhat different story? Fewer than half of the acquisitions that companies make generate value, according to BCG research. So as the engineering and construction (E&C) sector consolidates and the pool of worthwhile targets shrinks, a strategic (and more disciplined) approach to M&A becomes even more critical.

What can E&C leaders do to ensure that their M&A deals deliver value sustainably? How can they capture the other benefits that M&A can offer, such as reduced exposure to risk and greater adaptability and resilience—vital traits in a volatile, fast-changing era?

To answer these questions, we looked at recent M&A trends in the industries making up the E&C sector. In engineering, residential and nonresidential construction, and infrastructure, we found four broad strategies and specific practices that firms employ to unlock value in their deals.

Shifts in M&A Deal Trends

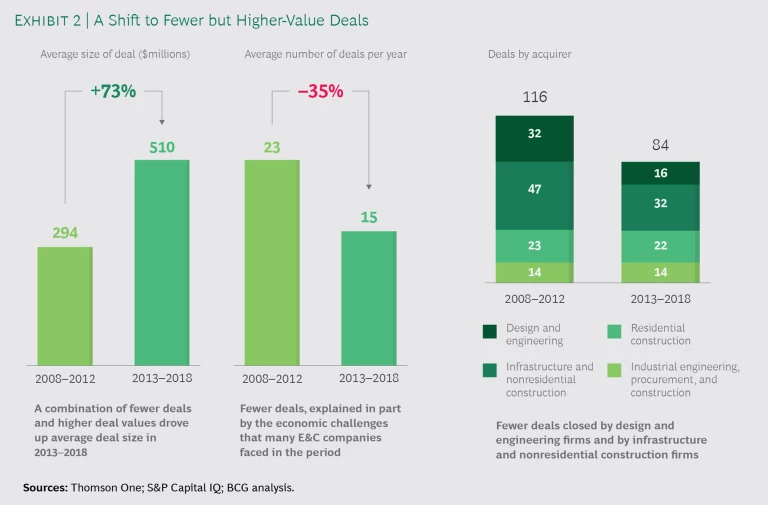

We analyzed more than 200 industry transactions from 2008 through 2018 and interviewed industry experts and top E&C executives who led their companies in M&A deals. Although total activity has remained fairly stable (between $8 billion and $10 billion in annual deal value), the broad trends—deal size, number, and type of acquirer—differed considerably between the 2008−2012 and 2013−2018 periods.

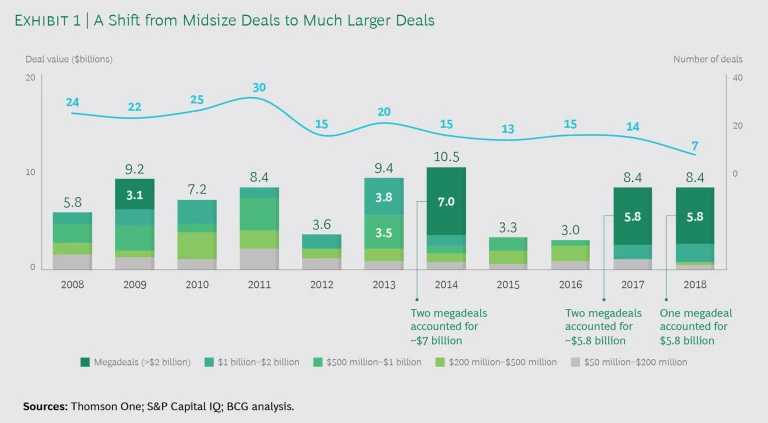

There was a distinct shift from a larger number of midsize deals from 2008 through 2012 (about 120 transactions averaging $300 million) toward fewer, bigger deals from 2013 through 2018 (about 80 deals, averaging more than $500 million). (See Exhibit 1.)

The average annual number of deals fell 35% between the two periods, from 23 to 15. In particular, there were fewer deals closed by design and engineering firms and by infrastructure and nonresidential construction firms. (See Exhibit 2.) The reduced small-deal activity from 2013 through 2018 can be explained in part by the economic challenges that many E&C companies faced during the period. The megadeals, though small in number—they included the 2014 acquisition of URS by AECOM ($6 billion) and Wood Group’s acquisition in 2017 of AMEC Foster Wheeler ($2.7 billion)—helped keep the overall value of M&A deals close to the level of the earlier, 2008−2012 period.

Why Pursue M&A?

M&A can create value for E&C companies in four distinct ways: by boosting revenues; boosting profitability; reducing exposure to risk and increasing agility and resilience; and helping companies prepare for digital disruption.

Boosting Revenues. M&A opens the door to new revenue streams by improving the company’s market positioning or broadening its geographic or sectoral footprint. Typically, revenue synergies in the E&C sector range from 6% to 25% of the target’s revenue (with a median of 14%).

In E&C, size is a particular advantage: it gives firms access to larger projects, enabling them to achieve faster absolute growth. Establishing a market foothold through organic growth can take time, especially considering the minimum local presence required for a company to operate. M&A offers companies a way to acquire the scale they need to establish, relatively quickly, a market presence that will lead to profitability and financial resilience. Size also confers access to projects previously unattainable because of the special know-how required or because of tendering requirements, such as references or access to funding and bonding.

M&A opens the door to new revenue streams.

Boosting Profitability. Cost synergies can improve profitability and overall competitiveness and are thus an important prerequisite for any deal. M&A helps E&C companies streamline most types of costs.

- Project costs, such as materials or equipment, can be reduced thanks to the greater bargaining power that companies gain with their main suppliers. Sourcing strategy and the way suppliers are bundled are two key levers for reducing operational costs. Firms that don’t take advantage of their scale and instead allow all procurement spending to continue at the individual project level are wasting value creation opportunities.

- Commercial and tendering costs can be trimmed in regions where the acquiring company and its target have overlapping operations. Scale alone helps reduce commercial and tendering costs. So does avoiding duplicative costs, such as shuttering redundant offices and having the ability to present a single combined bid.

- Overhead cost synergies are another source of value creation. In E&C deals, they generally range from 5% to 14% (median 7%) of the target’s total cost, although they can be higher in deals with a large proportion of overlapping activities (such as those located in the same region). Overhead cost synergies can be achieved by merging support functions such as HR, finance, and IT and by setting up shared services, which can yield greater economies of scale. To be competitive, construction companies, for example, should aim for combined overhead costs of 4% to 5% of total revenues once the integration is completed.

Reducing Risk Exposure and Increasing Agility and Resilience. Mitigating risk and enhancing the company’s ability to adapt to change are important goals of M&A. This is no minor consideration, as customers (including public-sector infrastructure agencies) increasingly shift project risk onto construction firms and other contractors. Even in the past few years, private clients, in particular, have become more strident in their claims of underperformance.

M&A helps E&C companies streamline most types of costs.

E&C companies can achieve these objectives in a number of ways. For example, a larger project portfolio enables a company to absorb more easily the shocks from nonperforming projects. Acquiring new business lines that have more stable cash flows (such as public-private partnerships and infrastructure concessions) can mitigate the volatility that comes from design or construction. And a more diversified geographic footprint reduces the impact of geopolitical risk from one or more specific markets.

Helping Companies Prepare for Digital Disruption. Although the E&C sector has hardly blazed the trail in digitization, companies are becoming more aware of the opportunities that digitization creates—and the risks of falling behind.

Increasingly, customers are demanding digital capabilities, such as building information modeling (BIM), from their contractors. The possibilities for digital innovation in E&C extend from project monitoring and reducing cost overruns (through, for example, data integration and analytics) to simplifying construction elements (via 3D printing, for instance). Other technological developments (the Internet of Things and AI), in tandem with skills shortages, could well accelerate adoption and spark disruption in the global market. While some companies are developing their own digital skills in-house, others are moving to buy these capabilities by acquiring digital specialists.

A larger project portfolio enables a company to absorb more easily the shocks from nonperforming projects.

Four Fundamental Strategies

Engineering and construction firms can follow any one of four broad-brush M&A strategies: venturing into new territory, pursuing adjacencies (or building new capabilities), regional consolidation, or vertical integration.

Venturing into a New Region. Making a local acquisition is a common way to establish a sustainable presence in a new market. It is also often the least risky and only practical way for foreign entities to successfully penetrate mature markets, such as the US and Germany, where established competitors have a foothold. The buyer can readily leverage the target company’s local know-how in the form of decision makers, suppliers, contractors, and the meeting of local requirements (such as bonding or strong references). Companies that have pursued this strategy include US-based Jacobs Engineering, which bought Sinclair Knight Merz in 2013 to secure a stronger foothold in Australia and broaden its presence in the oil and gas and chemicals sectors; Vinci Construction, which acquired Seymour Whyte in 2017 to enter Australia; and Swiss construction leader Implenia, whose 2015 purchase of Bilfinger Construction gave it access to Germany, Austria, Romania, and Sweden.

Adding or Bolstering Capabilities. For some companies, an acquisition is a way to add capability in adjacent market segments, such as an onshore oil and gas entity buying an offshore company. For others, the goal may be acquiring capabilities in a new technical discipline—for example, a construction firm seeking geotechnical or hydraulic construction expertise.

Take, for instance, the recent acquisition by Arcadis, a global design and consulting firm, of SEAMS, a provider of software and advanced analytics, to bolster its digital capabilities.

Consolidation. Here, a company seeks targets in the same business segment or the same region with the goal of becoming a market leader through cost efficiency and market positioning. Economies of scale make the acquirer significantly more competitive while boosting revenues and profitability. Such acquisitions are typically priced high because of the potential synergies or the substantial technical and commercial capabilities that have fueled superior performance at either or both companies.

When Lennar officially purchased CalAtlantic in 2018, it became the largest homebuilder in the US. The $5.8 billion acquisition gave the firm market leadership in 26 of the nation’s 30 fastest-growing metropolitan areas. It also gave it access to already entitled land that could be developed with one less source of delay. Along with reductions in cycle times and increased inventory turns, the acquisition helped provide much-needed skilled labor to keep up with demand—labor that had been in short supply since the Great Recession.

A more diversified geographic footprint reduces the impact of geopolitical risk from specific markets.

The acquisition of AMEC Foster Wheeler by Wood Group in 2017 was intended to create a global leader in engineering and technical services in the energy and industrial markets. This deal followed AMEC’s acquisition of its rival Foster Wheeler in 2014, which had made it a leader in oil and gas engineering.

Vertical Integration. Vertical integration means taking on more activities in the value chain, such as when a construction firm enters the operations and maintenance segment or when E&C firms merge to provide end-to-end design and construction services. Examples of recent deals focusing on vertical integration include:

- Fluor Corporation’s 2015 acquisition of Netherlands-based Stork Holding, a global provider of maintenance, modification, and asset integrity services to the oil and gas, chemical, petrochemical, industrial, and power markets.

- AECOM’s purchase of URS to create a “one-stop shop” for construction. URS offered formidable sector expertise in important end markets, including oil and gas, power, and government services. It also gave AECOM a bigger presence in Australia and New Zealand.

- Jacobs Engineering Group’s acquisition of CH2M Hill in 2017 added construction and operations and maintenance activities to the company’s portfolio. The two firms were complementary, overlapping only in infrastructure services (architecture, engineering, and design) and government services.

Vertical integration does more than broaden or deepen offerings: it promises greater insulation against risk throughout the portfolio. By diversifying their revenue and cash streams, companies are better able to weather market volatility and performance risks. In addition, their position in multiple segments of the value chain allows them to control the different types of risks inherent in concession-type projects.

How to Boost the Odds of Success

Prior M&A experience boosts the odds of success for any company; it’s little surprise that active buyers have a greater chance of achieving successful deals than those with little or no M&A experience. In fact, studies reveal that active acquirers are more likely to generate value than nonacquirers : their total shareholder return over 25 years is some 400 basis points higher than that of nonacquirers.

Most E&C companies aren’t seasoned acquirers, but that doesn’t mean neophytes can’t succeed or that veterans have nothing new to learn. From our client work and recent M&A activities, we have assembled a set of guidelines that incorporate key lessons and best practices to help companies derive the maximum value from any deal.

Prior M&A experience boosts the odds of success.

Predeal and Prenegotiation Musts

In their desire to consummate the deal, companies often overlook crucial steps that can undermine M&A success, including the following:

- Assess the strategic and operational similarities. Given all the focus on strategic fit, acquirers can overlook their target’s operational practices. Significant differences in operational standards—for example, in risk taking on bids or in project control—can be disruptive and impede integration. One acquiring company, which was typically risk averse in bidding on new projects, admitted to running into difficulties because it hadn’t looked into the culture of its target company—which had a decided appetite for risk taking. Knowing the target company’s culture and practices, particularly in such areas as bidding and project execution, is vital.

- Be comprehensive in conducting due diligence. In E&C, an acquisition is worth what its projects are worth. Hence, assessing the performance of projects in the target’s backlog is crucial to developing a proper valuation. But getting a reliable picture may not be easy, as disclosure isn’t always practiced. What’s actually happening on the ground is some of the most difficult information to obtain. Thorough due diligence can therefore take time. One action a potential buyer can take is to include clauses in the contracts that protect it from unwelcome surprises in legacy projects.

- Define a realistic synergy target. Defining the level of revenue and cost synergies during the case study requires careful consideration of different scenarios. Cost synergies are usually easier to assess and track; revenue synergies are generally harder to quantify and achieve. But companies that make a plan for them are more likely to achieve them. BCG research shows that companies that define a clear strategy for capturing and communicating synergies enjoy a higher valuation in the capital markets.

- Retain key talent. Identifying and retaining the target company’s key personnel is critical from the beginning. Aligning key positions, from executives to project directors, is essential to successfully transitioning the business to the new owner. Therefore, retention mechanisms, such as bonuses based on integration objectives, must be designed and implemented early on.

Postdeal Requirements

Some companies do top-notch predeal work but become lax with postdeal work. Some of the important actions acquirers should take include the following:

- Staff key positions in critical functions and projects with your own talent. Every acquirer needs guaranteed access to actual performance results and the ability to steer decisions based on its criteria for driving value. When it comes to staffing key positions in critical functional areas and projects, keeping executives in the acquired company motivated while implementing the acquirer’s ways of working can be a delicate balancing act.

- Put in place strict control mechanisms. It’s helpful to rapidly implement processes that monitor project progress and the cash flow generation of the project portfolio. Companies can also benefit from mechanisms that track synergies and ensure that all integration steps are followed as planned. BCG research has demonstrated that companies that systematically track postmerger progress achieve up to 35% greater synergies than initially announced.

- Ensure cultural alignment. Culture counts in an integration’s success. Even seemingly small cultural differences can disrupt and poison the effort. One executive told us that differences over risk control mechanisms in the project bidding and execution phases created major misalignment with the management team of an acquired firm. Successful dealmakers often implement initiatives to mitigate cultural differences in their integration processes.

E&C companies have grown increasingly selective in their M&A activities as they seek to strengthen their footprint and market leadership position while reducing integration risks.

Regardless of their strategy—whether they seek a foray into new territory, adjacencies or new capabilities, regional consolidation, or vertical integration—successful dealmakers share certain specific practices. Predeal, for example, they dig deep to understand their target’s potential value and pinpoint differences that could potentially disrupt the transaction. They implement guardrails, such as mechanisms for retaining key talent. Postdeal, they take a disciplined approach that prioritizes quick gains and cultural alignment—and that recognizes the importance of taking control of the bidding process and the execution of key projects.

Inorganic growth is an increasingly important means of value creation in a fast-changing world. As competitors gain in scale and power, the acquisition opportunities are shrinking. Those armed with the right mindset, guidelines, and guardrails will be better positioned to compete for promising targets—and enjoy long-term success.