In today’s dynamic business environment, virtually all companies will go through a stretch of bad performance. One in three public companies will cease to exist within the next five years; 50 years ago, the ratio was one in 20. Moreover, business organizations often decline much faster than they grow—a phenomenon known as the Seneca effect, named after the Roman Stoic philosopher who once observed, “Fortune is of sluggish growth, but ruin is rapid.” Some companies that find themselves in this situation try to wait these periods out, but others take dramatic, decisive action to turn things around and are able to generate results in a matter of months—ultimately spurring a strong recovery in performance. Furthermore, BCG research has found that preemptive change measures, launched before a state of overt crisis occurs, produce significantly higher long-term value than reactive change measures do.

To succeed in this value-based turnaround, management teams need to address short-term challenges while also setting up the organization for long-term, sustainable value generation. In addition, companies need to align the agendas of various stakeholders—investors, debt holders, laborers, and suppliers, among others—around a single, clear objective that meshes with the legal frameworks and managerial cultures of their respective markets.

To better understand how these principles apply to turnarounds in Italy, we recently analyzed companies across a wide variety of industries, including industrial goods, consumer goods, distribution and retail, health care, and technology. (See the sidebar “Methodology.”) Within that group, we identified companies that experienced a drop in EBITDA for at least two consecutive years and then launched a subsequent turnaround.

Methodology

Methodology

To identify the Comeback Kids, we started by looking at Italian companies with at least €500 million in revenue, assessing their financial performance from 2010 through 2017. We ruled out banks and insurers (primarily because they have specific accounting principles that don’t apply to other industries) along with energy companies (whose performance depends heavily on the price of raw materials, requiring a more qualitative analysis). We also ruled out firms that did not have reliable data on profits. For the remaining sample of companies, we identified those that experienced a drop in EBITDA for at least two consecutive years. Within that group of troubled companies, roughly one-third (32 companies) were able to successfully reverse the negative trend in profits and return to strong growth. These are the Italian Comeback Kids. We then looked at revenue, EBITDA, and total shareholder return, which includes both capital gains and dividends, for that group.

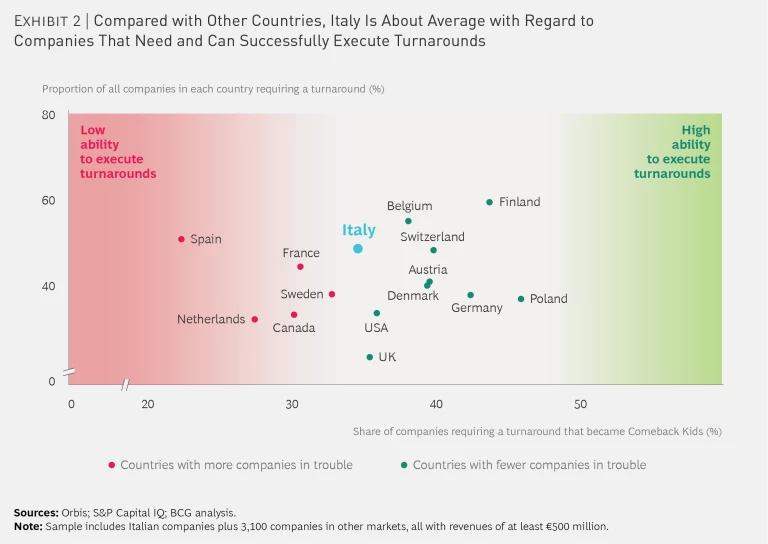

We also compared Italy with other countries in terms of both the need for companies to execute turnarounds (the share of companies that are experiencing a crisis in profitability) and their ability to execute turnarounds (the share of successful turnarounds compared with the overall number of troubled companies).

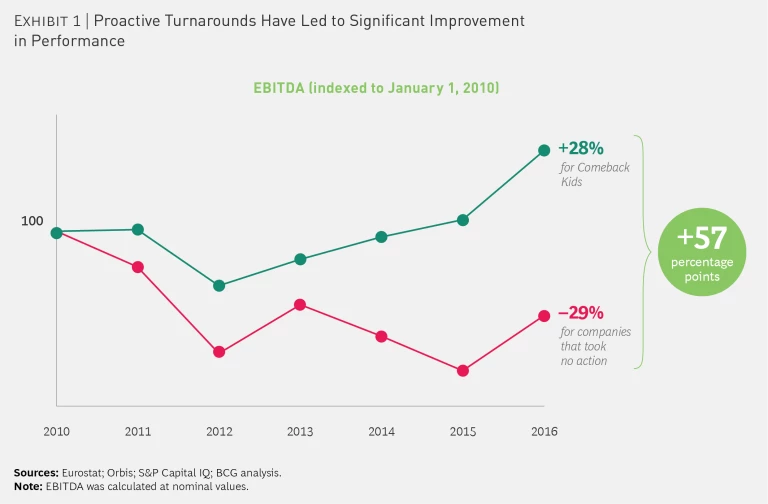

Notably, this group only represented one-third of all companies that experienced problems. But the improvement in financial performance for these Comeback Kids, as we call them, was striking: The full group of 32 generated an increase of 28% in EBITDA from 2010 to 2016, compared with just 6% for the full sample of 200 companies and –29% for struggling companies that were unable to execute a successful turnaround. (See Exhibit 1.) The average annual total shareholder return—a metric that includes both capital gains and dividends—for the Comeback Kids was 7% during our time frame, compared with –3% for the companies that missed their turnaround window.

How does the turnaround performance of companies in Italy compare with that of companies in other markets? We looked at countries in terms of both the need to execute turnarounds (the share of companies that are experiencing a crisis in profitability) and the ability to execute turnarounds (the share of successful turnarounds compared with the overall number of troubled companies). In both dimensions, Italian companies are roughly average. (See Exhibit 2.) Companies in Spain and the Netherlands showed a lower collective ability to launch successful turnarounds, but those countries also have a lower share of companies facing trouble. In contrast, companies based in Finland, Germany, and Poland showed the highest likelihood of turnaround success. The key takeaway: company leaders in Italy cannot point to market-specific factors as a reason for their success or failure in turnaround efforts.

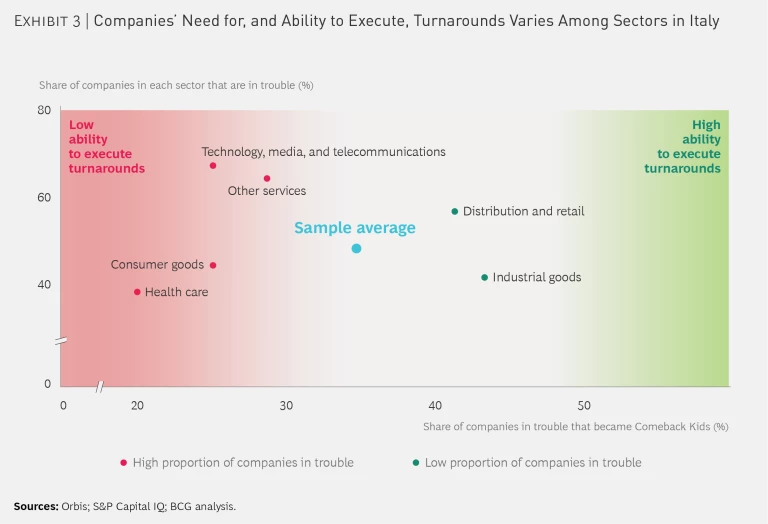

We conducted a similar benchmarking analysis to look at the turnaround performance of Italian companies by industry. (See Exhibit 3.) Companies in the industrial goods and distribution and retail industries were both more likely, on average, to be successful; those in health care and consumer goods were less likely to succeed. Most notably, the technology, media, and telecommunications (TMT) industry had the highest share of companies in trouble, and they were among those with the lowest ability to turn themselves around. This can be explained by the way that digital is constantly disrupting TMT segments, particularly established incumbent companies in telecom and media, which have deeply entrenched cultures.

Another key finding is that public companies showed a significantly better ability to implement turnarounds compared with nonlisted companies—a difference of 13 percentage points. One possible explanation is that listed companies have external shareholders that can lobby management teams to make needed changes. The performance of these companies is public, and there are consequences for management teams that do not deliver.

We identified four levers that Italy’s Comeback Kids used to execute a successful turnaround:

- Adjusting the portfolio, typically to sell off unprofitable or nonstrategic assets and refocus on core products, markets, and activities

- Redesigning the operating model to generate sustainable gains in efficiency and to lower costs

- Generating growth in new geographic markets and product segments

- Innovating in such areas as digitizing internal processes, creating omnichannel customer journeys, developing new products to better meet customer needs, and shifting to new service models

Most turnarounds include at least some aspects of all four levers, though perhaps at different degrees of emphasis and during different phases of the program. Finding the right equilibrium among them is one of the most critical choices that a leader must make in designing and implementing a turnaround.

The five stories highlighted on the following pages offer detailed case studies of how turnarounds play out in the real world. They span industries as varied as oil and gas, retail, and luxury, but they share one consistent message. Any company can find itself in a bad situation with declining performance—in fact, a downturn is almost guaranteed at some point due to technology disruption, new entrants, or some other cause—but the outcome is largely within the hands of management.

Leaders that can take a clear-eyed view of the situation and set a bold vision for improvement through a structured turnaround program can position their companies not only to recover but also to emerge with even stronger performance. Conversely, those that remain passive, with a wait-and-see approach, will find themselves overcome by the competition.

ERG Restructures Itself Around Renewable Energy

Energy company ERG has an 80-year heritage of strong growth. Over the decades, it completed a series of acquisitions that provided operations in coastal refining and downstream products, such as lubricants and fuels, including a network of 2,000 service stations. But in the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, market conditions began to turn against the company, with a corresponding drop in margins. By 2008, ERG’s refining operations, which made up 60% of total revenue, were posting EBITDA margins of just 1.6%—only one-third of where they were just three years earlier. Margins at ERG’s integrated downstream operations, which constituted another 32% of revenue, had fallen by half over the prior three years, to 2.3%.

Worse, market conditions for the near future looked grim. Oil prices had nearly tripled, to historic highs, from January 2007 to July 2008, triggering fears of a speculative bubble and virtually guaranteeing that prices would fall soon. At the same time, massive new oil refineries were opening in the Middle East. Not only could these refiners capitalize on locally sourced feedstock and strong government support, but they also had scale advantages because of their size and were more technologically advanced. As a result, they created a worldwide glut that threatened established competitors in the US and Europe.

There were macroeconomic headwinds as well. The global financial crisis dampened GDP growth and consumer confidence. Even after the crisis, the consumption of petroleum products in Italy declined at a compound annual rate of 4% from 2008 to 2015, compared with a decline in national GDP of 1% during that time.

If there was a bright spot, it was that ERG had a small renewables business generating energy from wind, an industry that was growing fast and increasing its margins. Moreover, new green regulations—such as a mandatory, progressive reduction in CO2 emissions and higher efficiency standards for buildings and vehicles—created incentives to invest in renewables. Those factors threatened ERG’s core oil business, but they created a tailwind for the renewables sector.

ERG’s small renewables business generated energy from wind, an industry that was growing fast.

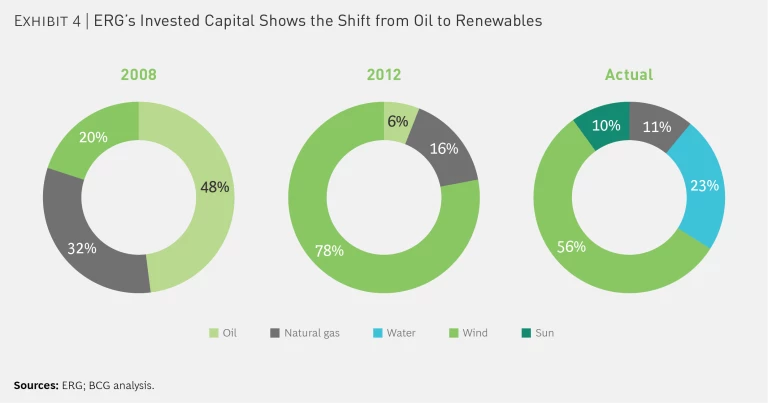

To capitalize on this shift, ERG launched a turnaround program to scale back its oil operations and reorient the portfolio around renewables. The company began a series of oil-linked disposals in 2008, totaling about €3.6 billion in deals by 2018, when the company was entirely out of the refining and service-station businesses. Over the same period, the company invested €4.3 billion in renewable assets in areas including wind, solar, and hydroelectric power generation.

The company’s restructuring was extremely ambitious. ERG essentially started as an oil refiner, then slowly morphed into an integrated energy company split between conventional and renewable sources, and ultimately became a focused electricity provider relying on renewable sources. Today, 89% of invested capital is allocated to renewables, and the remaining 11% (for natural gas) is earmarked for a combined-cycle cogeneration power plant, with high levels of efficiency and low emissions. That plant was the first and largest facility to earn the High Efficiency Cogeneration qualification by Gestore Servizi Energetici, the Italian government agency that promotes sustainable energy. (See Exhibit 4.)

In addition to restructuring the portfolio, ERG launched several other measures to support the turnaround: a cost-cutting initiative significantly reduced fixed costs, and management brought operations and maintenance functions in-house, leading to lower costs and higher efficiencies. ERG also went through three reorganizations (in 2010, 2013, and 2017) to realign existing divisions and functions around the company’s changing needs. As part of those reorganizations, the company developed internal expertise in key areas. For example, it improved operation, maintenance, and construction skills to become increasingly competitive in operating cost management, and it developed energy management skills to boost profits through electricity sales transactions. Moreover, a business development team was set up to create the basis for organic growth and long-term development in European target countries.

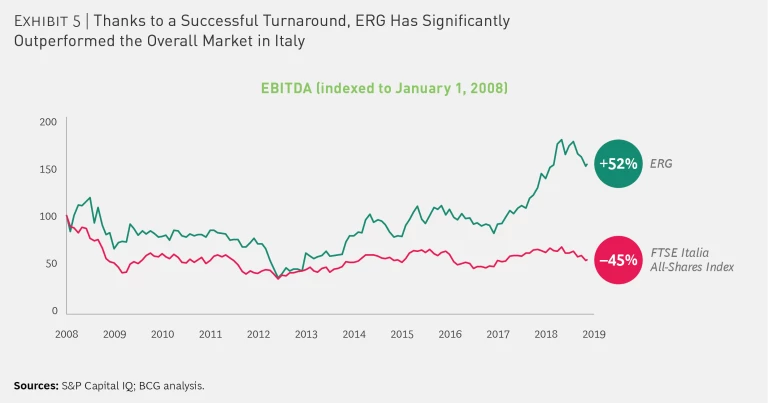

Overall, the turnaround has positioned ERG as a smaller and far more profitable company than it was 11 years ago. EBITDA margins have increased by about 40 percentage points, to almost 45% as of 2017, thus guaranteeing an EBITDA similar to that prior to 2008, despite a decline in sales to one-ninth of the level before the turnaround. The company also used some of the proceeds from asset sales to strengthen its capital structure, and it paid out more than €1 billion in dividends during the period from 2008 to 2018. ERG’s share price has increased 52% since the beginning of 2008, compared with a decline of 45% for the benchmark FTSE Italia All Share index. (See Exhibit 5.) The total shareholder return for ERG during the same period, including dividends, was 150%.

In hindsight, there were several factors behind the company’s success. First, management had the foresight to take bold action early on: even though oil assets had accounted for most of the company’s revenue throughout its history, ERG shed them when the extent of the crisis was still unclear, ensuring a prompt repositioning for the long term. Second, the company adequately funded the turnaround, using the disposal plan to guarantee cash for its growth in the new core sector. Finally, ERG put the right organizational measures in place to sustain performance throughout the turnaround and over the long term.

As a result, ERG is now a leader in renewable-sourced electricity, and its shareholders have been richly rewarded.

Versalis Goes Global and Leverages the Circular Economy

The chemical company Versalis is a subsidiary of the well-known Italian energy giant Eni, which dates back to the 1950s. Versalis was created through a series of deals—often not pursued with a clear strategic view—as part of a decades-long process to privatize the parent company. Eni’s petrochemicals business pioneered several major developments, becoming one of the first producers of petroleum-based plastic and synthetic rubber. Eni was formerly owned by the state; now about 70% of the company’s shares are publicly held. The Italian government holds the remainder through so-called golden shares that allow the state to retain control.

In 2012, during a challenging period for the industry, Versalis launched a strategic turnaround. Following the financial crisis, economies in the European Union—the source of 90% of Versalis’s sales at the time—were slow to recover, leading to slack demand. In addition, new plants were opening in the Middle East, where government-owned players could source inexpensive oil locally.

Those external factors affected the entire petrochemicals sector, including Versalis. But the company faced several internal challenges as well: Its acute focus on commodity products resulted in few opportunities to differentiate or create value through specialization. Worse, many of its facilities operated as standalone entities, with little integration among one another. That put the company at a significant disadvantage because most of its European competitors specialized more in higher-value products. As a consequence of both external and internal factors, Versalis faced annual losses of hundreds of millions of euros.

In 2012, Versalis launched a strategic turnaround to tackle both internal and external challenges.

The turnaround had four main objectives. First, the company launched a multiyear initiative to revamp its production facilities. Some plants were sold off, others were closed (raising capital that allowed Versalis to fund the longer turnaround journey), and the company reconfigured many of the remaining plants to make them more efficient.

Second, the company repositioned itself for growth by diversifying its product portfolio. The company shifted from the traditional commodity products that it had long focused on to more advanced chemical products and breakthrough approaches, such as using renewable feedstock and conducting “circular economy” projects. For example, one facility in Porto Torres, Italy, moved from petrochemicals to bio-based manufacturing, with products that use vegetable oil as a raw material. In another initiative, the company formed a technology joint venture with a biotech company to develop bio-butadiene (a raw material for rubber) from sugar.

Third, Versalis began building up its already sizable portfolio of proprietary technologies and know-how and then leveraging the portfolio to expand its international network. For example, it opened a new production site in South Korea in a joint venture with a major local player. It also extended its commercial network outside Europe, with the goal of increasing sales in higher-growth markets, such as Asia and the US. To that end, Versalis established commercial subsidiaries in Shanghai, Mumbai, Singapore, and Houston.

Fourth—and most important—Versalis sought to make the turnaround sustainable by putting the right organizational elements in place. It created a more dynamic and innovative corporate culture, with greater motivation and engagement among employees. While working to increase trust and teamwork, the top management encouraged open communication across all levels of the organization. So, rather than fearing change and being forced to react to market disruptions, the company now emphasizes its technical know-how and strong legacy of expertise. The company has about 30 such technologies and more than 300 patents, along with five research centers; the R&D and technology and engineering functions alone comprise more than 350 scientists. Versalis then began leveraging the portfolio to expand the company’s international network. With this solid foundation in place, Versalis reinforced its brand reputation as an innovator that can create value by bringing new ideas to the market.

Versalis reinforced its brand reputation as an innovator that can create value by bringing new ideas to the market.

Throughout the turnaround, Versalis focused on having the right team in place at each stage. The executive suite understood that each phase of the turnaround would require a different style of leadership. The company systematically identified change management leaders and built a resilient and proactive team—with complementary skills and competencies—to steer the overall program. It also monitored the organizational climate to gauge morale and engagement among the workforce.

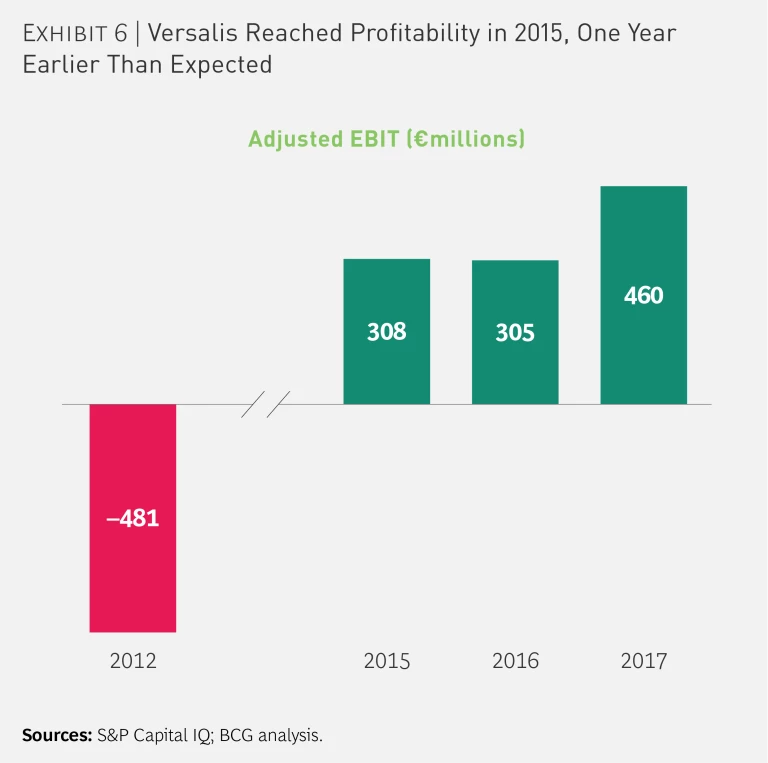

The original goal of the transformation was for the company to return to profitability by 2016. Versalis beat that goal by one year, posting more than €300 million in adjusted EBIT in 2015. (See Exhibit 6.)

Today, the company’s transformation continues. Its renewed vision—as presented at BCG’s Value-Based Turnaround conference (in Milan in May 2018)—includes a firm commitment to the circular economy with the development of a new business model based on product innovation and ecodesign, feedstock diversification, and polymer recycling projects.

With the right production network, commercial footprint, product portfolio, technical know-how, and organizational culture in place, Versalis is now well positioned to continue on its development trajectory.

Autogrill Refocuses on Its Core Catering Business

Autogrill is a familiar name to European travelers. The company runs catering operations in highway service areas, airports, and other travel hubs. Dating back to the 1950s, Autogrill, along with several of its competitors, was nationalized by the Italian government in the 1970s and then privatized again in the 1990s. Along the way, the company diversified into two smaller businesses: travel retail outlets (primarily in airports) and in-flight catering. But throughout the first decade of the 2000s, the catering operation made up about two-thirds of Autogrill’s revenue, and that business was heavily weighted toward highway service areas. Out of nearly 1,100 locations, 710 were on highways, 367 of which were in Italy alone.

From 2007 to 2013, the profit margins of Autogrill’s catering operation decreased steadily, from 13% to just 8%. The financial crisis led to lower traffic volume as travel in Europe declined. And the company suffered from its portfolio focus on highway locations in the mature European market, because new roads were unlikely to be built in the region. Inorganic growth was challenging as well; the company had been investing in acquisitions for its other businesses but not for its core catering operation.

In 2013, therefore, Autogrill launched a turnaround program with three main objectives. First, the company repositioned its portfolio of businesses to focus on catering. It sold its in-flight catering operation, generating significant value in the form of both capital gains and dividends for investors, and broke out the travel retail unit into a separate entity, creating additional billions in value for shareholders. Though it might seem that travel retail would have synergies with travel catering, in fact the overlap is minimal and limited to combination leases or concessions for the same location. Moreover, the company saw a far more attractive growth opportunity in its core catering business.

The second phase of the turnaround focused on developing the catering business. Autogrill started to de-emphasize its presence in service areas in Italy, where future growth was limited; it did not replace expired concessions in some locations; and it sold its interest in locations with low volumes. From 2013 to 2015, the number of Autogrill’s concessions on Italian highways declined by 12%, even as the revenue per location increased slightly. Autogrill maintained the number of concessions on highways in the rest of the world, but it increased revenue by shedding poor performers. The company also sold some of its concessions in train stations, shopping malls, and downtown city centers—again focusing on the best performers and shedding lower-volume sites. As those parts of the portfolio shrank, Autogrill opened new concessions within airports—a more promising channel for catering. The number of airport concessions grew by 4%, and revenue for the airport channel grew even faster, by 18%. Geographically speaking, the growth was even more significant in northern Europe and in the US. In the US, in particular, Autogrill capitalized on HMSHost, an American food service company that Autogrill acquired in 1999. Overall, this refocus on different locations around the world played a key role in Autogrill’s turnaround.

Refocusing on different locations around the world played a key role in Autogrill’s turn-around.

In the third component of the turnaround, the company invested to transform its core catering business, innovating to develop new formats, products, and processes. The overall goal was to make the restaurants more attractive and increase the average size of sales. To improve the customer experience, Autogrill implemented digital technologies, launching an app and installing kiosks. It also used digital to increase efficiency, centralizing and automating some operations and processes.

The catering business steadily increased from €4 billion in 2013 to €4.6 billion in 2017, and profits grew from €314 million to €403 million. That strong financial performance translated to an increase in the company’s stock price. Since 2013, that price, including dividends, has increased at a compound rate of 18%.

Through the initial divestment of the in-flight catering operation and travel retail businesses, and during the turnaround of the catering business, Autogrill has focused relentlessly on creating value for its shareholders.

Ferretti Group Builds Its Financial Position and Commits to Luxury

About 50 years ago, two brothers, Alessandro and Norberto Ferretti, acquired the rights to sell boats in Italy made by the American company Chris-Craft. Starting with a single store in Bologna, Ferretti Group took advantage of the unprecedented growth of the Italian boat industry, reaching a record high revenue of €1.1 billion in 2008. The company is now one of the most prestigious luxury yachts makers in the world: its boats are routinely featured in lifestyle magazines and are docked in such illustrious locations as Monaco and Cannes. Unfortunately, an excessive use of debt, along with poor decisions by management, caused the company to begin navigating rough waters when the global financial crisis hit in 2008.

The demand for high-end yachts, as for most luxury goods, shrank significantly as a result of the crisis. From 2008 to 2012, yacht sales in Italy fell by 88%, to a low of just €200 million. Ferretti’s capital structure was not prepared to absorb the shock. The company had been acquired by a private equity fund in the first few years of the 2000s, and its debt rose to more than €1.2 billion at the end of 2008. While the company needed extraordinary initiatives to change course and minimize the impact of the financial crisis, the initial measures adopted by the management team to revamp the business did not succeed. Ferretti remained in the center of the storm.

A new opportunity for the company arose in 2012 when Weichai Group, a Chinese enterprise that manufactures diesel engines, signed on as a majority shareholder. Unlike other equity firms that had invested in Ferretti in the past, Weichai did not overload the company with new debt; instead, it allowed the management team to adopt a longer-term strategic orientation. Ferretti received a sizable cash injection from the deal, which helped to pay down existing debt and provide needed liquidity. Weichai also ensured that strategic suppliers would continue to be paid, safeguarding the supply of critical production components.

The turning point of Ferretti’s turbulent voyage came at the end of 2014, when the company brought in a new CEO to lead what would become its comeback. The CEO appointed new executives in all key positions. The influx of talent brought additional capabilities and managerial know-how from such sectors as automotive and aeronautics, and the company launched several turnaround measures.

The turning point of Ferretti’s turbulent voyage came at the end of 2014, when the company brought in a new CEO to lead what would be-come its comeback.

Specific actions concentrated on boosting revenues while maintaining Ferretti’s heritage of artisanship. Management repositioned the company to focus on a category of vessels that were even more luxurious (bigger yachts with a wider range of personalization opportunities and unique solutions)—a category that is less vulnerable to economic downturns. In parallel, the standardization of some components across yachts saved costs and simplified the entire supply chain. Shipyards also benefited from a significant modernization effort.

In 2016, another Italian investor—F Investments, run by the Ferrari family—acquired 13.2% of the company and became the perfect partner for Weichai. This strong ownership structure proved to be a great enabler for Ferretti, allowing it to reinvest profits internally and fuel further growth. To support the overall plan, Ferretti invested more than €150 million, €91 million of which was spent on R&D to redesign part of the fleet and develop new models. Results were extremely positive, with two-thirds of sales in 2016 and 2017 coming from these new models and platforms.

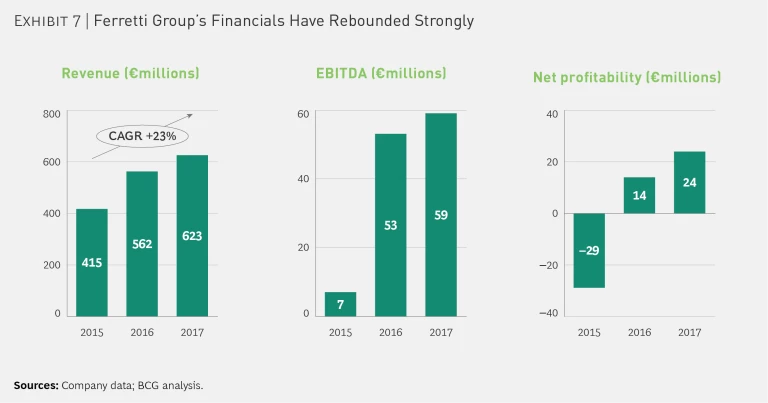

The turnaround implemented by the new leadership team over the past five years restored Ferretti’s positive financial performance and became a legend within the shipbuilding industry. Revenue grew from €415 million in 2015 to €623 million in 2017, with EBITDA and net profitability steadily increasing. (See Exhibit 7.) By contrast, the rest of the luxury yacht industry has posted negative margins since 2017.

Ferretti’s successful turnaround is going to set a new benchmark for Italian luxury players. It proves the importance of installing a forward-looking management team and establishing a strong partnership with long-term investors. Moreover, the decision to keep production sites in Italy allowed Ferretti to preserve its brand equity, quality standards, and technical expertise. Now that the company has emerged from the crisis, it is leading the market and equipped to navigate through all kinds of weather.

Piazza Italia Returns to Growth by Overhauling Its Business Model

Founded in 1993, fashion retailer Piazza Italia built its brand around a winning strategy: affordable prices and a retail network of stores located on main city squares in Italy, other European markets, and the Middle East. In the five years leading up to 2016, the company’s revenue grew by about 8% each year, thanks to ambitious efforts to open new stores. But other key metrics—such as same-store sales and sales per square meter—were not keeping pace as the company got bigger, and profit margins were declining. The main problem was that the company was buying too much inventory and then either heavily discounting it at the end of each season or simply not selling it at all.

In early 2017, Piazza Italia launched a turnaround to boost its financial and operating performance. The program had five key levers:

- Improve the Buying Process. The company built a structured plan and process to focus on product categories that showed a strong growth trajectory, increasing the incidence of fast fashion.

- Reduce Discounts. Piazza Italia revamped its approach to promotions and sales campaigns in order to reduce discounts. It developed new sales campaigns and changed the goal from simply selling inventory to ensuring that a customer wanted to return.

- Better Manage Unsold Stock. The company also put systems in place to reduce unsold stock, including tracking and warehousing goods from previous seasons and integrating them with offerings from the current season.

- Align Decisions Across the Company. Piazza Italia established enterprise-wide standards for decision making. Previously, different business units and functions had significant autonomy, which led them to pursue their own goals instead of the overall company’s goals.

- Develop the B2B Online Business. Piazza Italia developed business relationships with a few of the main leaders in fashion e-commerce, which will be one of the main sources of future growth for the company.

The turnaround is still being implemented, but it has already generated significant impact, with some €2.5 million in increased EBITDA adjusted in 2017; it was forecast to improve in 2018.

Discounting has declined dramatically, and sizeable increases of 2018 gross margins (up to 4 percentage points) and EBITDA (up to 3 percentage points) over 2016 were projected.

In all, the program positioned Piazza Italia to evolve beyond its entrepreneurial roots. The company has continued to grow, and it is now restoring its profitability, delivering strong returns to its shareholders, and positioning itself to thrive in a dynamic retail environment.