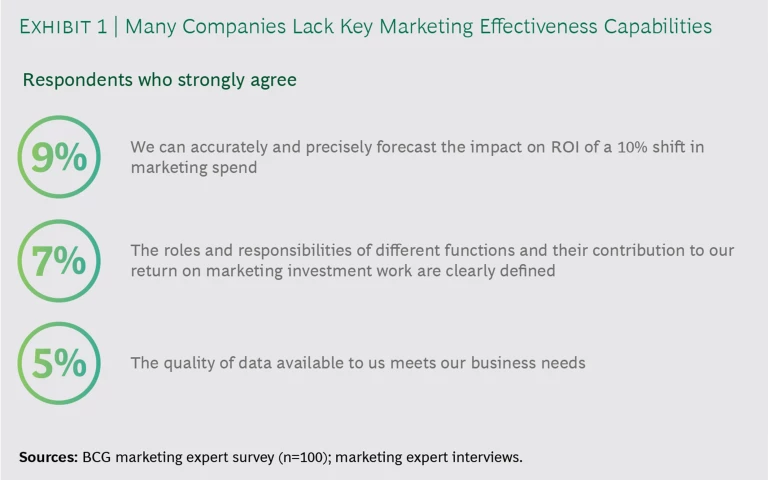

It’s hardly news that marketers leave money on the table. That’s been a frustration since the earliest days of measuring marketing. But even in 2019, as digital-ad spending surpasses 50% of all ad spending, nine out of ten marketers say they are leaving big money behind because they’ve failed to develop the capabilities they need to know what’s working. Don’t take our word for it. This is the self-assessment of more than 100 CMOs and senior marketing executives at leading companies in seven consumer-facing industries in the US. (See Exhibit 1 and “About This Report.”) And big money means exactly that: our research shows that companies that develop the necessary capabilities can expect to see a 20% to 40% improvement in spending efficiency and as much as a 10% increase in marketing effectiveness .

ABOUT THIS REPORT

ABOUT THIS REPORT

This report is based on a survey of 100 US-based senior marketing executives (who collectively manage nearly $20 billion in annual marketing budgets) and on more than 30 hours of in-depth interviews with senior marketers covering such subjects as marketing measurement, capability building, and incrementality. The companies included represent seven consumer-facing industries: automotive, consumer packaged goods, financial services, media, retail (general and luxury), telecommunications, and travel and leisure.

This report was produced in collaboration with Facebook and the findings outlined herein were discussed with Facebook executives, but BCG is responsible for the analysis and conclusions.

It seems axiomatic that companies should be able to track effectiveness more precisely than ever before. But most organizations lack confidence in their measurement capabilities. Why? And what are the leaders doing that sets them apart? Our research and experience suggest that there are three ways that the best marketers create the behavioral change necessary to develop highly effective marketing measurement capabilities. The changes involve breaking down barriers and creating a base of cross-functional support, adopting more agile ways of working and a culture of experimentation, and focusing incentives on improving marketing performance.

Tools Are Not Enough

Sophisticated marketing functions employ high-quality toolkits to ensure that they are gathering the information and insights they need to identify what’s working at different points along the customer’s buying journey . They can accurately predict the impact of spending increases in various channels. As the global marketing director of one CPG company said, “We complement our sophisticated analytical tools with other measurement methods. It’s important because we recognize that our marketing mix model doesn’t measure and attribute perfectly across channels.”

Predicting and measuring marketing incrementality is critical to setting future spending levels. Incrementality has multiple definitions, but our research found that only about 25% of marketers measure incrementality in any form for most of their activities. The majority can forecast marketing effectiveness within a few specific channels, but only 9% say they can forecast incrementality for all channels, with traditional (nondigital) channels being the most challenging. Few run experiments devised specifically to measure the incremental impact of campaigns or their component parts. (See “A Few Definitions.”)

A FEW DEFINITIONS

A FEW DEFINITIONS

Marketing measurement uses terminology that includes common words with specific meanings for the marketing context. Here are a few used in this report.

Incrementality. The process of measuring the contribution, or “lift,” above a defined baseline that is attributable to marketing above and beyond other factors. Marketers use multiple definitions of incrementality, from the broad (the sales lift achieved from an increase in spending) to the quite specific (the degree to which a measurement method estimates the true causal effect of an isolated marketing activity). The most common definition is the additional revenue contribution from marketing above and beyond any other baseline factors. Incrementality can be estimated through predictive modeling. Experiments add a high degree of accuracy to these models through measurement.

Predictive modeling. Models such as marketing mix models and multitouch attribution models that leverage historical data to estimate the uplift of marketing overall and by channel. Predictive models provide an estimate of incrementality; they are used for high-level spend allocation and vary in interpretability.

Experiment. An effort to precisely measure incrementality and determine causality using two similar groups and randomly applying a marketing activity to one (test) group while withholding it from the other (control) group. Determination of causality can in turn be used to calibrate predictive models.

One reason for the difficulty is that sophisticated tools require a robust data infrastructure, which is a challenge for many marketers because the infrastructure depends on widespread access to data, the right systems, and technical talent. Another is that achieving a full view of what’s working is hard work. There is no single measurement solution. Companies need to deploy a comprehensive approach employing a suite of methodologies, such as marketing mix, multitouch attribution, and other forms of modeling, to get a full picture. This is especially true if they want to predict the impact of changes in spending in individual channels.

But predictive models can vary widely in their accuracy and ability to forecast incrementality. For this reason, more mature marketers also use consumer research, competitor benchmarking, experiments, and other tools to measure the effect of tactics across channels. Understanding what motivates consumers, and how to communicate and motivate based on these insights, is critical to managing customer purchase journeys. Experiments can help to reveal the individual drivers of incrementality and the impact of each one. They can thus help to calibrate predictive models. “For us, constantly testing and running experiments has built an agile marketing engine, where we are able to launch experiments quickly, get frequent readouts of results, and act on them to improve both incrementally and continuously,” said the senior director of marketing analytics for a major retailer. But many marketers still do not experiment. Our research found that among those who use marketing mix or multitouch attribution models, only 60% also use experiments.

It Takes a Team

Marketers (including the biggest spenders) struggle with organizational barriers to teamwork, both across the business and within the marketing function itself. Cross-functional support (from sales, finance, product, IT, and others) can supply the necessary skills and perspective for capability building and help set accountability for reporting. But this kind of collaboration can be tough to achieve. As one CMO told us, “A key barrier to success for us was cultural inertia and an attachment to the way marketing had always been done. It takes discipline to move past preconceived ideas of how things should work, and not everyone has it.”

Marketers (including the biggest spenders) struggle with organizational barriers to teamwork, both across the business and within the marketing function itself.

Some of the most detrimental barriers restrict access to data, the lifeblood of effective marketing measurement. For example, only 42% of companies in our survey reported that the quality of available data is sufficient for their business needs. And only 21% have a clear strategy to close data gaps. At the same time, though, the need for a consistent data infrastructure can help facilitate better cross-functional collaboration. One automaker recently sought to focus its organization on gaining a full view of the customer journey. Management initiated a program of cross-functional conversations involving business units and functional departments. These sessions used multiunit data first to define profitability and then to determine how it would be measured across the company and what success would look like for the manufacturer as a whole. In addition, management used this high-profile push to begin a culture shift toward more integrated processes and data infrastructure in order to improve collaboration going forward. When the project was finished, the company set up a cross-functional steering committee to ensure longevity and “stickability” of the changes.

Organizational barriers may be exacerbated by different measures of profitability, separate data systems or vendors, varying sets of metrics, internal politics, or differences between digital and traditional processes. For example, marketers often point to success with tools that others neither understand nor trust. Or they cite metrics that are not broadly recognized across the business as having value.

Companies also encounter barriers to data access with vendors that undermine the ability to generate insights in-house. The head of digital marketing for a travel company described the challenge this way: “It took us six months to bring in all the middle-of-funnel data that was being housed with our agencies. We needed to coordinate internally with IT and externally with our analytics platform and agencies. I talked to my agency partners almost every day. Did I drive them crazy? Probably. Was it worth it? Absolutely.”

Often it takes intervention from the entire C-suite, with the CEO as the ultimate advocate, to break down broader business silos. Nowhere can the tension be more pronounced than between marketing and finance. “Initially, finance didn’t have confidence in our reporting and methods, and we felt they didn’t understand the value of branding,” a CMO told us. “We had lively discussions about how to define metrics. I eventually brought finance in closer, to dig into our agency reporting. They were more objective and sophisticated about measurement, and they offered us great insights on how we define our metrics.”

There is no perfect organization structure; leading companies find the design that works best for them. But any organization has the potential to wall off departments or functions, and our research shows that breaking down barriers can help companies improve marketing measurement, no matter their level of sophistication. For example, the strongest companies are three times more likely than their weaker counterparts to synthesize data from all marketing teams before making budgeting decisions.

A Culture of Experimentation

Measuring marketing effectiveness often depends on a top-down mandate and culture setting from leadership. “The single biggest unlock for us was a new CMO who was progressive and dedicated to change,” said the senior director of marketing management for a telecommunications company. This can be uncomfortable. The head of marketing for an automotive OEM told us, “I warned our executive team that I was going to bring them insights from data that they wouldn’t want to hear, and they said, ‘Go for it.’ It’s not easy to get over your fear of change, but they did it—and if they hadn’t, we wouldn’t have been able to jump-start growth.”

One big change is to embrace experimentation, which by definition involves failure. To that end, more and more marketers are turning to agile ways of working. Agile works by focusing on principles over practices, putting the right leadership in place, and establishing alignment to enable autonomy . When agile is implemented successfully, we have seen big increases in effectiveness and satisfaction and commensurate reductions in cost. It’s not easy, however: in a recent BCG survey, almost nine out of ten marketing executives said they consider agility very important, but only one in five believe that their companies are sufficiently agile.

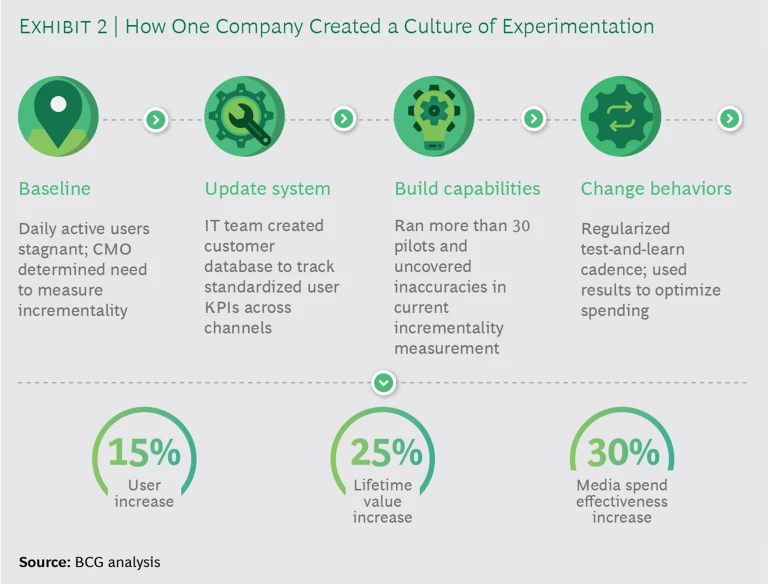

A culture of experimentation drives continuous improvement and rigor. This involves taking on a hypothesis-driven approach, hiring talent skilled at and comfortable with testing, and developing the ability to integrate learnings into marketing planning for ongoing improvement. (See Exhibit 2.) Some leaders earmark a portion of their budget for experiments or testing new methods (for example, 70% tried and true, 20% tested and promising, 10% new experiments). They also encourage their teams to try new things, push those that seem promising, and declare failure quickly with the others.

“Our priority became hiring the best talent for our digital team,” said the manager of digital marketing for a telecommunications company. “We actually laid off quite a few employees and replaced them all with fresh talent in a different region. With the right people in place, we achieved 40% year-over-year sales growth with the same marketing spend.” The digital marketing vice president of a financial services firm put it this way: “I don’t want my team to have a background in media or digital. I’m looking for a test-and-learn mindset—people who question why we do things the way we do and focus on solving problems, instead of chasing the latest hot platform.”

“I’m looking for a test-and-learn mind-set—people who question why we do things the way we do and focus on solving problems, instead of chasing the latest hot platform.”

Several leaders whom we interviewed mentioned their struggle against “lifer syndrome”—the cultural inertia and fear of change of longtime executives. Many executives need to learn the Do You Have the Courage to Be an Agile Leader? —and doing so visibly—thereby releasing teams to figure out how to address their assigned challenges.

Creating such a culture can be a bigger challenge than it first appears. Being good at experimentation and testing and learning (with an emphasis on learning) takes four steps:

- A hypothesis-driven approach to deciding what to test

- Rigorous setup and execution

- Statistically valid measurement based on prealigned metrics and KPIs

- Scale it or fail it—making sure that the learnings turn into actions

Ensure Consequences

Incentives matter. The organizations that tie compensation to marketing measurement and performance tend to include full assessments of marketing effectiveness in strategic decisions related to both budgeting and longer-term planning. Three-quarters of marketers who submit performance metrics to annual strategic-planning exercises believe they have a well-functioning process for understanding their return on marketing investment (ROMI). Only 22% of those not required to submit such metrics have a similar belief.

Marketers who apply specific measurement initiatives, such as experiments, generate hard data and instill discipline in determining the right cadence, metrics, and data sources for marketing decisions at all levels of the organization. They avoid being ruled by what we call the tyranny of random facts —each marketing manager citing a fact or data point revealed by some unique tool or model. “If a method didn’t measure incrementality precisely, we simply ran small tests that would show us directionally if it worked,” said the vice president of content marketing for a financial services firm.

As with any incentive program, focusing on the right KPIs is key. A smaller set of KPIs can help marketers make decisions more effectively. The director of analytics for a travel company told us, “Our dashboards focus only on essential, effective metrics. We simplify our dashboards over time, instead of stuffing them with ‘chart junk’ that’s impossible to read.”

The most sophisticated companies look at marketing ROI as a corporate objective. They tie marketing measurement to broader business objectives and integrate marketing into business decisions. This means developing cross-functional marketing KPIs that can drive value for the broader business (such as by increasing customer value versus driving additional click-throughs).

One financial services firm achieved a big increase in sales by more closely aligning incentives with marketing metrics. It used a new CRM system to link the sales and marketing funnels and created a system to align sales incentives and marketing metrics across the combined funnel. It created dashboards from the new CRM system that provided visibility into individual sales performance. The changes revealed weak performers and recognized formerly unnoticed “unsung heroes.” Sales increased by more than 30%. “We’ve become an organization of closers, not hunters,” the CMO said.

Real Improvement Takes Time

While they are essential, good tools, data, and experiments will not improve marketing measurement by themselves. The missing link, as our most recent research highlights, is the organizational capabilities that embed measuring effectiveness in the marketing operating model. Only 34% of the companies in our study have a dedicated function for assessing ROMI, and only 37% have clarity in roles with respect to marketing measurement. In fact, organizational structure is consistently ranked as the weakest component of companies’ ROMI capability.

Organizational structure is consistently ranked as the weakest component of companies’ ROMI capability.

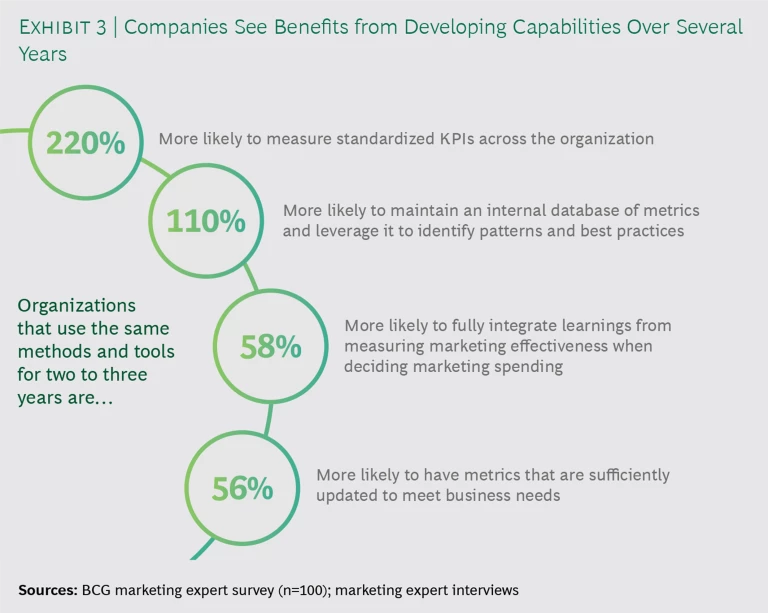

Achieving the benefits of upgraded organizational capabilities and effecting the needed underlying behavior change typically take two to three years. For example, companies that have had their measurement toolkits in place for two or three years are more than twice as likely to have consistent, standardized ROMI KPIs. “It takes a year of everyone questioning a new model until we have enough history to believe in it,” said the vice president of marketing for an automotive OEM. “We usually needed 12 to16 months to show a smooth trend that we could rally support behind.”

Such timeframes are a challenge for many marketers because their efforts tend to start and stop according to executive turnover, resulting in continual change in the partners and vendors involved and challenges in recruiting talent. Methods and tools must be well engrained in operations before metrics can be standardized across the organization. “We did a lot of work setting up new data infrastructure and hiring an analytics team to improve our methodology and make marketing effectiveness part of our culture,” said a retailer CMO. “Now that we have the foundation, I’m interested in sourcing tools that plug into our data to enable standard reporting—that’s not something we have yet.”

There is a payoff to patience and persistence, however. As Exhibit 3 shows, organizations that keep the same methods and tools in place for three or more years are more likely to:

- Develop standardized KPIs across the organization (often a streamlined set of prioritized metrics) that meet business needs and aid in decision making.

- Integrate learnings from marketing measurement when determining spending.

- Identify and codify best practices.

Move Forward or Get Left Behind

The good news for marketing functions is that, regardless of starting point, the road to building better organizational capabilities and improving measurement effectiveness is well charted and results are readily achievable—so long as the company is committed to the effort over the long run. By focusing on incremental improvement, even the most sophisticated companies have room to develop, provided they don’t let perfect be the enemy of better.

Wherever a company starts, some no-regrets moves will show results if management sticks with them. Companies need to develop (or acquire) a full suite of tools, including the predictive models that enable assessment of incrementality and the research that furthers consumer understanding and generates usable insights. They should augment these tools with experiments that boost accuracy for individual channels. (Earmarking an adequate and explicit budget for experiments—5% to 10%, for example—and establishing a rigorous and transparent prioritization process can be a good starting point for a top-down experimentation mandate.) Marketers need to break through the organizational barriers that limit access to data and constrain cross-functional collaboration, reaching out to and enlisting the relevant cross-functional stakeholders in team efforts around shared goals. Agile ways of working can both enhance collaboration and speed campaign development and time to market. Agile also facilitates development of a culture of experimentation that uses test-and-learn methodologies to improve campaigns in real time. Developing the right incentives is key, as is having the patience to build an organization that is geared to achieving outcomes and results.

There is no quick way to improve marketing measurement. To be effective, it must be a corporate KPI. Success requires a long-term commitment, deliberate thinking and planning, and concerted organizational and cultural change. The sooner companies start down this road, the sooner they’ll see important needles move.

For more on how measurement strategies like incrementality and experimentation are helping marketers make more effective decisions, visit

fb.com/incrementality

.