This article is a chapter from the BCG report, The Most Innovative Companies 2019: The Rise of AI, Platforms, and Ecosystems .

In 2016, a group of Finnish medical researchers won a global competition to predict prostate cancer survival rates accurately. From an innovation perspective, two facts stand out. First, the competition was virtual: it was hosted and managed on a cloud-based platform that facilitates scientific collaboration. Second, before entering the contest, the Finnish team had not been active in cancer research.

As we noted in our 2016 report on the most innovative companies, innovation today can come from anywhere—and more and more frequently, it comes from outside the company. (See The Most Innovative Companies 2016: Getting Past “Not Invented Here ,” BCG report, January 2017.) Technology has helped level the competitive playing field, making it easier for anyone anywhere to gain access to the hardware, software, and tools they need to develop new ideas and business models and connect with other people and organizations.

At the same time, companies can use an array of tools to cast wide innovation nets and get an early look at what’s happening in their targeted fields of R&D. (See How the Best Corporate Venturers Keep Getting Better , BCG Focus, August 2018.) It’s a powerful combination—if companies create the organization, processes, and incentives necessary to bring outside ideas inside without killing them along the way.

It’s an External Game

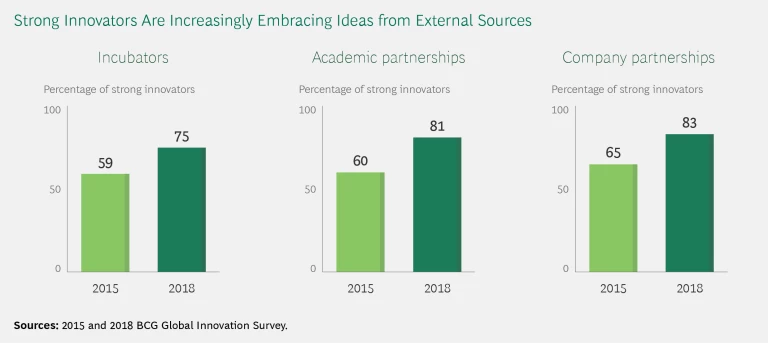

In business life today, companies need to look beyond their own walls for new ideas. We have seen big increases in the use of such partnership models as corporate venture capital, incubators, and accelerators. Our current innovation survey found that incubator use among self-described strong innovators rose from 59% in 2015 to 75% in 2018, that tapping into academic relationships jumped from 60% to 81% during the same period, and that formation of company partnerships increased from 65% to 83%. (See the exhibit.)

The increasing use of platforms such as Synapse, which hosted the prostate cancer challenge, is making innovation more multiparty and collaborative. There are many types of platforms—such as computing, technology, service, content, and marketplace—but all of them serve a similar purpose. Users access platforms because platforms combine aggregated supply or demand with high service levels and reduced friction. They can also facilitate collaboration and the development of new ideas. For example, many of the longest-tenured companies on our most innovative companies list use platforms to gain access to different capabilities and sources of data, which they then use to build new business models or develop new products and services.

Developers of voice-recognition-based smart home platforms, including Amazon and Google, make it easy for others to create new consumer services that use their AI-enabled platforms—and in the process to attract the critical mass of applications needed to make their platform a clear leader. (See the companion article, “ AI Powers a New Innovation Machine .”)

Digital technologies enable collaboration platforms, and collaboration platforms enable ecosystems that bring together a group of organizations to build a new capability or product or service offering, or to help a new field of science or technology advance. Some ecosystems represent expansions of traditional ways of organizing and doing business; they tend to have an orchestrator at the center, with which all the other participants interact, along with established hierarchies and structures.

Other ecosystems—including many that are involved in the early research phase of R&D—tend to be more dynamic, less reliant on a central orchestrator, and more dependent on multifaceted interactions among participants. Various types of glue bind ecosystem participants. Money is one type of glue, of course, but knowledge, data, skills, and community can be equally important.

Many ecosystems involved in the early research phase of R&D depend on multifaceted interactions among participants.

Just as multiple types of platforms exist, ecosystems may be formed to serve different purposes. Here are some of the most common ones that are relevant to innovation.

Building Capabilities. Many ecosystems are set up to bring in expertise from other industries. BCG research shows that 83% of digital ecosystems involve partners from four or more industries and 53% involve partners from six or more industries. For instance, a household electronics manufacturer might partner with sensor and camera manufacturers, an AI software provider, and research facilities to bring an advanced vacuum robot to market. In the past, to enter a new market (such as China), automakers either formed a joint venture or alliance with an OEM or established contractual relationships with hundreds of suppliers to secure parts. These traditional partnerships still exist, but today a typical European auto company draws on an ecosystem of more than 30 partners across five different industries and several countries to make their cars connected, electric, and autonomous. The auto company acts as orchestrator, organizing and managing the ecosystem, defining the strategy, and identifying potential participants.

For example, Caterpillar’s smart-mining ecosystem involves four types of collaboration, with a strong focus on flexible deal structures such as partnerships and minority investments, along with joint ventures and M&A. Caterpillar has forged partnerships to improve its proprietary industrial IoT platform's technology, and it has made minority investments to expand the platform’s automation, optimization, and analytics capabilities. For most companies, these types of flexible deals require a different approval process than prevails in traditional contracting and M&A—one that is faster, leaner, and closer to the business. (See “ The Emerging Art of Ecosystem Management ,” BCG article, January 2019.)

Developing New Products and Services. Ecosystems can offer multiple players a powerful way to build new revenue streams from products and services that they could not develop and bring to market on their own. For example, Alibaba’s ecosystem provides a range of services for Alibaba platform users: travel, entertainment, gaming, finance, transportation, and e-commerce. It’s an eclectic mix, and it generates a wide-ranging array of data that Alibaba collects and analyzes centrally. By capturing data from multiple sources, Alibaba can tailor individualized offers to users—timing them for maximum effectiveness—and provide tools that help its online sellers enhance their own businesses. The results, in turn, provide more data for the ecosystem.

In recent years, Alibaba has expanded on this model to build Ant Financial Services (originally Alipay) into a major force in financial technology; today, it is the world’s most valuable fintech company, with more than 520 million users. Using machine learning technology and data from the Alibaba ecosystem, Ant provides an array of financial services to an underbanked market. Alibaba’s data and analytics capabilities enable Ant to assign credit scores to individuals and small businesses, and the company has ventured from payments into online wealth management and consumer and small-business lending. In 2017, Ant launched two new initiatives: a payment option that uses facial recognition technology; and Ant Forest, which uses digital gaming technology to enable users to track their carbon footprints. The service has already attracted some 200 million users. (See “ Digital Innovation on the World Stage ,” BCG article, May 2018.)

Collecting and Using Data. Data ecosystems will play a critical role in defining the future of competition, particularly in many B2B industries, because they enable companies to build data businesses. Such businesses are valuable not only because they generate recurring high-margin revenue streams, but also because they create competitive advantage. New data-driven products and services deliver unique value propositions that extend beyond a company’s traditional hardware products, deepening customer relationships and raising barriers to entry by others. They also build highly defensible positions rooted in economies of scale and scope, similar to positions based on proprietary intellectual property (IP) or trade secrets. (See “ How IoT Data Ecosystems Will Transform B2B Competition ,” BCG article, July 2018.)

Data ecosystems will play a critical role in defining the future of competition, particularly in many B2B industries.

Gaining Access to IP. Shifts in the IP marketplace are creating new opportunities for companies that are long on IP to cooperate with traditional companies that may be short on it. Many tech companies, for example, have a surplus of IP, while industrial goods companies may face a deficit. In the IoT world, they can work together to expand the market for sensor-enabled and location-aware goods and services. Classic, exclusionary IP strategy is not dead, but companies need to master a more sophisticated and nuanced playbook for creating competitive advantage through IP. (See “ The New IP Strategy: Make Love Not War ,” BCG article, June 2018.)

Merging Physical and Digital Channels. B2B and B2C companies are finding new ways to combine the digital world and the physical one to provide new services, more seamless customer experiences, and—in some cases—new business models. Amazon (with its acquisition of Whole Foods), Siemens (IoT), and the auto industry (connected cars and autonomous vehicles) offer examples. Emerging opportunities at the intersection of the digital and the physical give incumbents the chance to innovate and build valuable ecosystems by defining new niches and new rules. (See “ Getting Physical: The Rise of Hybrid Ecosystems ,” BCG article, September 2017.)

Advancing New Technologies. Companies that have a stake in basic scientific advances or in the development of new technologies such as quantum computing or synthetic biology may want to explore emerging deep-tech ecosystems—groups of entrepreneurs, startups, investors, corporate and academic partners, and others that join forces to research and develop a particular technology. Such technologies differ from others in their expected impact, in the time they take to reach market-ready maturity, and in the significant amount of capital (and investor patience) required to bring innovations to market. The ecosystems represent a new model that is far more fluid and dynamic than the methods used to conduct technology R&D in the past. (See The Dawn of the Deep Tech Ecosystem , BCG report, March 2019.)

Some Rules of Ecosystem Engagement

An ecosystem often operates differently from other types of business partnership, and in ways that can be foreign to big companies. Because ecosystems are dynamic environments that tend to contain lots of varied entities, they have multiple sources of influence, and no one party absolutely controls their direction. They trade in multiple currencies, not all of which are financial. Because they exist to create value through collaboration, they are the opposite of zero-sum congregations; when the ecosystem wins, each of the participants wins as well. And they evolve, acquiring new members and missions over time. (See “NTT Docomo’s Evolving Mobile Ecosystem.”)

NTT Docomo’s Evolving Mobile Ecosystem

NTT Docomo’s Evolving Mobile Ecosystem

Today it sounds like something from a distant era. In 1999—eight years before the launch of the iPhone—NTT Docomo (number 36 on the list of 2019’s most innovative companies) built the first mobile internet ecosystem in Japan.

The leading telco developed a vertically integrated ecosystem based on partnerships and acquisitions that provided valuable services and experiences to feature phone users. Part of its plan was to drive “innovation through the convergence of mobile with other industries and services, thereby creating new values and markets.” (See Through the Mobile Looking Glass, BCG Focus, April 2013.) Consumers flocked to new services such as mobile email, contactless payments, and, in time, streaming live video—all part of Docomo’s “i-mode” ecosystem, which helped propel mobile phones to become Japan’s most widely owned device and spurred traditional industries to go mobile. Docomo pioneered the technological innovation of mobile payments, leveraged local market dynamics, and achieved critical mass through partnerships with established players (often industry leaders). Establishing mobile payment capabilities for rail service helped seal other deals in the finance, retail, and hospitality sectors, among others, and helped attract more than 500,000 merchants to Docomo’s mobile payment service.

Since the advent of smartphones, Docomo’s ecosystem has undergone major evolutionary changes a couple of times. The first major change involved creating a mobile content hub through alliances with publishers, media companies, and other content producers. Docomo now offers more than 400 magazines online, as well as Japan’s largest anime library. Its dTV service has a similar number of subscribers to Netflix in Japan. As the content business has become more competitive in recent years, Docomo has moved to the latest iteration of its ecosystem, which relies on its strengths in payments, user identification, customer loyalty, and other areas to offer promotional support and services to an expanding network of third-party e-commerce partners.

Companies that are considering orchestrating a new ecosystem or joining an existing one should take a number of steps in advance to prepare themselves:

- Make sure that you have a sharp, clear innovation strategy that identifies the innovation domains on which you will be concentrating.

- On the basis of your innovation strategy, clearly articulate an ecosystem strategy: what value you want get out of an ecosystem, and what you need to achieve in the ecosystem to support your broader innovation goals.

- Identify the types of players with which you will interact. These may extend beyond the obvious choices to companies in other (unrelated) industries, universities and research institutions, startups, and venture investors, among others.

- Think about how you will enlarge the ecosystem pie other than by simply maximizing value for your company alone. Consider how the ecosystem as a whole will create value and how the participants will share that value.

- Note the locations of current innovation hot spots around the world for the domains you are targeting. The US and China are primary hubs for many fields of new-technology R&D, but many other countries are active in particular fields and are developing serious centers of excellence. (See “A Deep Dive into Deep Tech Investing,” BCG infographic, forthcoming.)

- Determine the kinds of relationships that will provide the foundation of the ecosystem, and decide on the nature of your involvement. For example, do you foresee a series of passive corporate venture-capital investments or active investments and collaborations? Is access to data more important than financial return?

- Align and manage your innovation vehicles (including their geographic locations, search patterns, guidance, and budgets), according to your answers to the preceding questions.

- Set clear goals, review achievements regularly, and don’t be afraid to adjust your ecosystem strategy on the basis of real-world results.

The use of platforms and ecosystems will undoubtedly expand as more companies experiment with both types of vehicles and develop more successful use cases. The relentless advance of technology will also play a role. The more complex the technology, the narrower the expertise—and the more likely it will become that companies must look outside their own organizations for the skills to use the latest developments. But gaining access to the latest science is one thing. Bringing that science inside and integrating it with existing programs and processes is another. The latter remains the area where most companies will face their biggest challenges.