As creators of value, North American banks more or less marched to the market for the past five years. Only the top quartile of the largest North American banks in our survey outperformed the S&P 500 Index on the basis of total shareholder return (TSR) and then only narrowly—11% versus 8% a year—for the five-year period from 2014 through 2018. The rest of the sample trailed the market index by an average of 3 percentage points. Throughout the period, large banks in particular were hampered by capital and regulatory constraints put in place during the financial crisis and, more recently, by stock market headwinds. Going forward, management teams at large banks in the US and Canada will find themselves freed of some of these shackles and needing to make difficult decisions about strategy, business mix, and capital allocation.

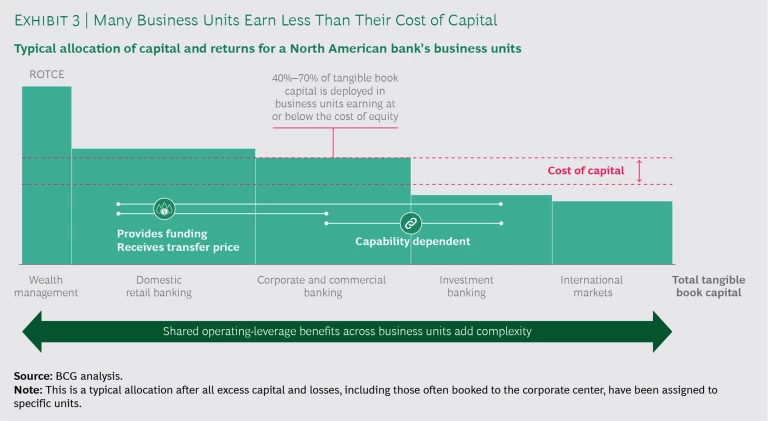

Banks that want to break out have plenty of work to do. For the 24 institutions that we analyzed—national, super regional, and regional banks that collectively represent approximately 80% of North American banking assets—the average return on tangible common shareholders’ equity (ROTCE) has hovered near the cost of equity since the financial crisis. At many banks, half or more of EBIT comes from business units that earn below their fully allocated cost of equity—an unsustainable situation from a value creation point of view.

Bank management teams understand this; they need to take a closer look at business units that fail to earn their cost of capital. But addressing these issues is not easy. For most large banks, the linkages and synergies among business units are a major strategic consideration, and they complicate making calculations strictly on the basis of financial return. Banks that want to materially improve their value creation posture may need to think in terms of transforming their business mix (and in some cases, changing how they conduct business), which takes time. Acquisitions and divestitures could be part of the package.

Banks need to take a closer look at business units that fail to earn their cost of capital.

In this report, we look at where large North American banks stand today from a value creation perspective and suggest a framework for taking strategic and operational considerations into account as banks chart a way forward.

Value Creation: An Uneven Picture

Value creation as measured by TSR is the true bottom line for any business. From the shareholder’s perspective, TSR is easily measured (by combining the share price gains and dividend yield for a company’s stock over a given period of time) and benchmarked. For operations managers, it’s helpful to disaggregate the primary drivers of TSR.

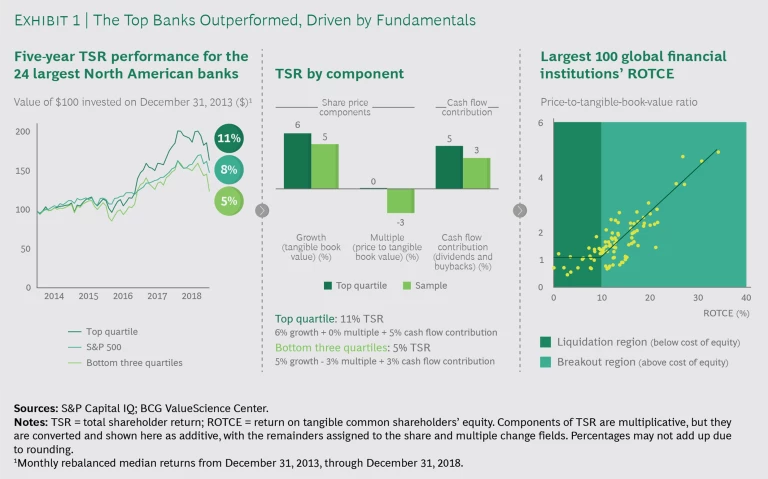

Our analysis of the TSR performance of the 24 largest North American banks over the past five years shows that top-quartile institutions created superior value by increasing tangible book value at a slightly faster rate than the rest of the sample while maintaining their valuation multiples. The remaining banks grew tangible book value almost as quickly, but their multiples contracted—a sign that returns were below the cost of equity or that other fundamentals were weakening, especially in the second half of 2018. Top-quartile banks were also able to return cash to investors at a faster rate in the form of dividends and buybacks, both important components of TSR. (See Exhibit 1.)

Large universal banks that combine retail banking and broker-dealer operations (such as Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase) also benefited from the reduction and eventual elimination of the discount to their fundamentals that investors assigned coming out of the financial crisis. For a number of years, markets feared that the potential for further scrutiny and regulatory pressure meant that for large banks, the whole was worth less than the sum of the parts.

Using empirical analysis is not only possible but also advantageous when deconstructing valuation multiples and understanding how a bank’s shares trade in public markets and which financial KPIs investors take as signals of a healthy (or unhealthy) business outlook. It’s also a fact that while growth is a major driver of value, aggressive growth can be a high-risk, high-reward proposition, and “bad” growth is a common cause of long-term TSR underperformance . This is highlighted by the fact that top-quartile banks and others saw similar increases in tangible book value over the past five years, but top-quartile banks increased their price to tangible book value (P/TBV) multiples because they grew efficiently.

BCG’s Smart Multiple methodology shows that in banking, TSR performance can be broken down into three components: the change in a bank’s P/TBV multiple, changes in TBV itself, and how—and how much—capital is returned to shareholders. The factors that influence the multiple positively in the North American market are the predicted ROTCE and dividend payout ratio; earnings volatility and bank size have a negative impact. Predicted ROTCE has the biggest effect, driving more than half the variation in the P/TBV multiple. Because of ROTCE’s substantial impact on the multiple, management teams should acutely focus on returning capital to shareholders that cannot be effectively deployed in operations. If a bank does not return this capital, tangible book value will grow, but the decline in ROTCE as a result of inefficient capital deployment will have a negative impact on the bank’s multiple and reduce TSR.

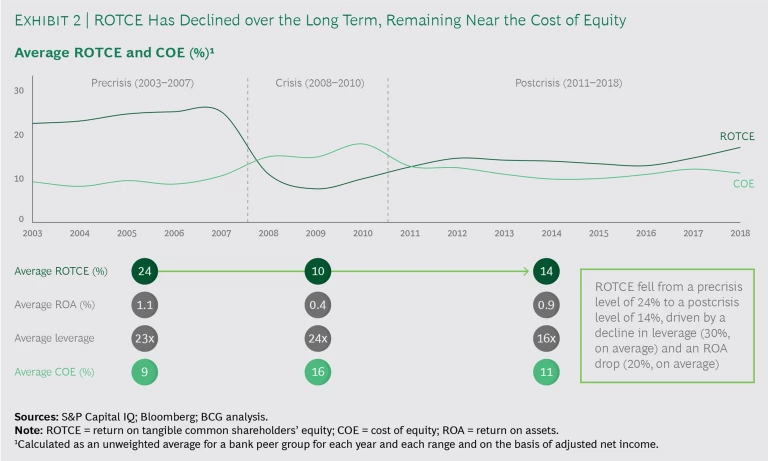

ROTCE is a useful lens that banks can use to assess overall performance and how individual business units are doing. Many large banks have started to emphasize ROTCE in their annual reports and investor presentations. Our analysis of the 100 largest global financial institutions shows that banks that earn above their cost of equity expand their P/TBV multiple, while those that earn less than their cost of equity trade in the “liquidation region.” The average ROTCE has hovered near the cost of equity since the financial crisis—the result of lower returns on assets in a low-interest-rate environment and reduced leverage caused by higher capital requirements—and the average remains well below its precrisis peak. (See Exhibit 2.) ROTCE has been climbing over the past few years as interest rates began to rise. Current capital requirements make it unlikely that most banks can reach previous highs without a very sizable increase (on the order of 50%) in the return on assets.

Within this macro environment, 40% to 70% of bank income comes from business units that earn less than their fully allocated cost of capital, a situation that clearly does not bode well for the future. (See Exhibit 3.) Worse, there is no quick or easy fix. It is difficult for banks to enter and exit business lines quickly, to truly allocate all costs and synergies to individual business units, or to shed all of the costs (tech and overhead, for example) absorbed by individual business units. It’s also hard for banks to effectively redeploy capital, or return it to shareholders, fast enough to drive higher returns. Even if a bank determined that it should shrink its size by 20%, achieving that kind of reduction quickly or returning the freed-up capital to shareholders expeditiously would be almost impossible because of regulatory approvals. If the bank redeploys the capital to other business units with higher ROTCE, the returns of those units could diminish if the capital is not used effectively.

Strategic Choices for Capital Allocation

Some time ago, our colleagues observed that most companies must “grow uphill,” because they face maturity and commoditization (both of which erode advantage) or disruption and changing customer behaviors (both of which erase advantage). These circumstances certainly apply to banking in North America. But making even small changes in the trajectory of profitable growth can create substantial value. Our research shows that over longer time frames, mature companies that increased their top-line growth even modestly (by 2 percentage points or more) delivered shareholder returns that were 40% higher than the market average .

Deciding where to try to grow requires strategically choosing how to deploy capital. Many bank CEOs and CFOs are already asking themselves the following questions about their business units:

- Can we transform the current businesses (through digitization or greater scale, for example) to generate better performance, or will performance improve only under fundamentally different business conditions?

- How important are these businesses to our overall portfolio?

- What is the long-term strategic value of operating in these businesses?

Answering these questions is far from simple. Banking’s business model linkages force management to take a comprehensive approach to thinking about capital allocation and return optimization. The relationships between retail banking, for example, and other business lines, such as investment and commercial banking, need to be considered, particularly with respect to operating leverage and the size of the bank, both currently and in the future. Retail banking generates funding for other lines of business. Investment banking provides commercial banking with capabilities and expertise in equity and debt capital markets, while commercial banking serves as a valuable distribution channel and referral source for investment banking. All business lines gain operating leverage from the bank’s central services (including IT and compliance) and capabilities (such as finance and legal). The interconnectedness in banking often makes it difficult to measure accurately the returns across different business units and to manage the competing interests of internal stakeholders. Both challenges can undermine management’s ability to achieve internal agreement about a particular strategic course of action.

Linkages force management to take a comprehensive approach to capital allocation and return optimization.

Making the decisions more complicated still is a crowded economic and business landscape. The combination of low rates and relatively low risk during the most recent economic cycle has both attracted new competitors and prompted many banks to pursue growth aggressively—even if it is to their detriment. Large banks especially must consider a host of operational and financial factors (such as their current market positions, assets, and ability to transition quickly to a new business model or models) and the regulatory environment (including required capital levels, flexibility for returning capital to shareholders, and M&A potential) when setting their long-term courses.

Banks also need to look at each of their businesses through a series of lenses to determine the best path forward for creating value.

Financial Performance. Relevant questions for each business include the following:

- Is the business strategically sound? That is, does it have an attractive market, a stable-to-improving outlook, and a source of competitive advantage?

- What are the right financial targets and KPIs for the business?

- How should ROTCE performance be assessed, and can it be measured at the same granular level as financial analysis and planning?

- What would a 20% increase or decrease in tangible equity look like? Where are the potential investments? What would be the impact from shrinking?

Business Linkages. To assess the role of each business and its impact on the broader portfolio, consider such questions as these:

- What is the purpose of the business in the portfolio, and what are the implications of pursuing growth versus efficiency?

- What are the true impacts of risk-weighted returns for all parts of the business?

- How could potential market shifts affect overall operating leverage, and how quickly could change happen?

- How could such changes affect client relationships, and which relationships are critical for the franchise?

Strategic Outlook. To evaluate the role of each business over the medium to longer term, ask these questions:

- How important is the business to the bank’s operations, and what is the size of its profit pool?

- What potential disruptions and competitive threats are on the horizon?

- How could acquisitions, additional commitments, restructurings, or divestures affect assets?

- What are the must-do big bets that will drive value in the next decade?

Improving Performance

For banks that want to outperform in their chosen lines of business, positioning themselves to grow uphill may require a process of transformation, perhaps combined with M&A. Weaker TSR performers need to transform their portfolios and improve ROTCE through a tighter focus on financial management before turning their attention to growth.

Business transformation used to be synonymous with cutting costs or building margins. Today, however, most business leaders recognize that How to Boldly Transform: An Imperative for Today’s Business Leaders . Leaders need to address the following:

- How should they position their organizations to win over the medium term (typically a three- to five-year horizon) in an environment where growth is difficult, competition is intense, and technology is changing the world around them? For most, this means identifying their value propositions and opportunities for growth, developing new operating models, engaging in business model innovation, and building new capabilities.

- How can they fund this journey by reshaping business portfolios and improving productivity? It’s important for a bank to notch some quick wins that demonstrate progress and build momentum while bigger initiatives for the medium term are in early stages. Opportunities include identifying new revenue streams, reducing costs, and simplifying the organization.

- How should they sustain improved performance over time? Banks need to build up the desired leadership, culture, and organization for the businesses that they want to create and that can drive growth. This will require acquiring new skills and capabilities. Digital technologies will be important, as will a more agile approach—one that is based on testing and learning as well as failing fast and cheap in various functions, including IT, product development, marketing, and distribution.

Most regional banks have already taken cost control and reduction about as far as they can. We are now seeing some regionals shift their focus to driving more top-line growth. Reaching the next level of operating model efficiency requires digital and technology transformations. Because of the need for significant investments, scale provides advantages—particularly in such areas as marketing, data, digital, and technology—that can lead to superior performance in the market. Large banks are demonstrating stronger organic growth, and they are boosting spending in key categories at an accelerating pace.

As we discuss in the next section, recent bank combinations have called into question the minimum scale required to compete effectively, and M&A is returning to the top of the strategic agenda. But deals depend on circumstance, such as the right target being available. Absent a transformational M&A transaction, banks must work to beat the scale curve by knowing their customers better than the competition and tightening their focus on profitable segments, regions, and niches. Banks must also use all the transformation levers available, including using data to make step changes in core capabilities (such as collections and credit), employing artificial intelligence and machine learning to automate processes, digitizing and simplifying the operating model, and partnering with digital leaders to offer new products and services.

Recent bank combinations have called into question the minimum scale required to compete effectively.

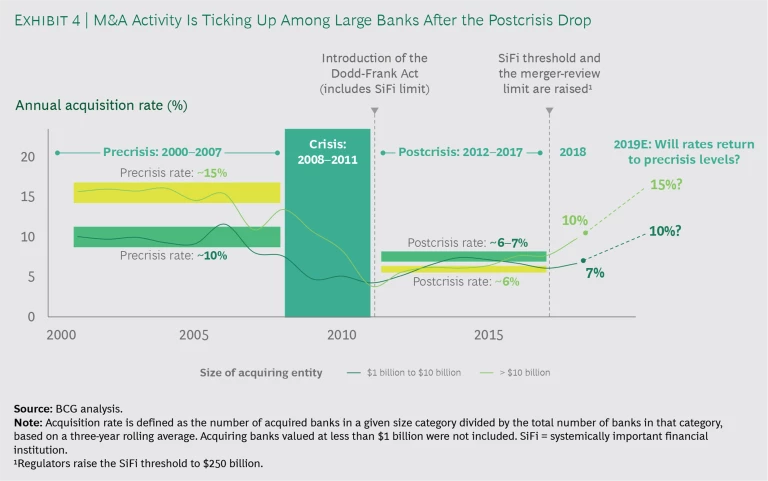

The Return of M&A?

In the last decades of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st, M&A played a big role in the creation of today’s major North American banks, both national and regional, as management teams sought operating economies of scale, local synergies, and a full portfolio of products, services, and capabilities. The global financial crisis and a tighter regulatory environment put M&A on the shelf for a number of years, but activity is beginning to pick up again, driven by many of the same goals as well as new trends. (See Exhibit 4.)

The new trends include the following:

- The need for greater digital and technology investment in such areas as fintech products, services, and capabilities.

- The need for access to more (and more types of) data, since it is the fuel for advanced analytics and artificial intelligence capabilities.

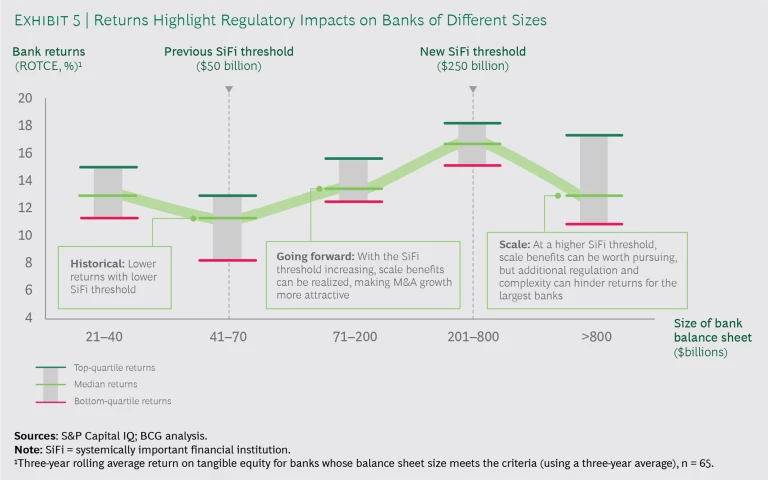

- Regulatory easing, especially for midsize banks (those with assets from $50 billion to $250 billion). Regulatory moderation includes the increase in the threshold for systemically important financial institutions to $250 billion, a relaxation of stress testing, and the exemption from the Volcker Rule of banks with less than $10 billion in assets.

- The reduction in the US corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%, which makes divestitures of fully depreciated assets considerably more attractive. At 35%, a deal needed substantial synergies to overcome the tax bill; under the new rate, after-tax proceeds from asset sales will increase by up to 22% , depending on an asset’s tax basis.

- Rising regulatory thresholds with respect to size that remove some artificial barriers to M&A growth, such as the increased costs associated with more extensive regulatory requirements. (See Exhibit 5.)

After years on the sidelines, banks (especially would-be acquirers) may need to sharpen their M&A skills. Research repeatedly shows that half or more of all deals fail to create value. Our experience tells us that the most common traps can readily be avoided. Acquirers need to carefully identify and assess the right target , accounting for the strategic fit (including the strategic rationale and competitive dynamics and the value of the acquisition based on gaining competitive advantage), the financial synergy case (through an unbiased, neutral lens), and the cultural fit (as a precursor to post-merger integration planning).

When acquirers decide to move forward, they need to prepare for critical integration aspects starting immediately. Our experience shows that successful acquirers that pursue systematic post-merger integration do more than augment total shareholder value . Markets “buy” their synergy story early in the deal and factor it into the share price. And markets reward these companies later, when they have proven that they can deliver on their promises, by showing confidence in their future corporate deals.

A majority of large North American banks went through a so-so five-year period from a TSR perspective. A few rose above the challenges, outperforming their peers and the broader market. The hurdles for all players will be higher going forward. Banks need to determine where their opportunities for profitable growth can be found and how to adjust their portfolios and their expense bases accordingly. Since this could take time, and the journey is likely to be complicated, keeping investors apprised of plans and progress against key milestones will be important considerations.

We have observed before that sector fundamentals are not an excuse for lagging value creation. TSR is relative as well as absolute; every company has the opportunity to surpass its peers. The performance of large North American banks as a group may or may not improve, but it is still possible for individual institutions to deliver superior shareholder returns.