It could be the half-trillion-dollar elephant in the global energy industry room. We estimate that more than 50,000 offshore wells and 10,000 offshore structures will be decommissioned worldwide along with hundreds of thousands of onshore wells, facilities, and sites. Since our previous estimate just over a year ago, that undertaking has increased by 50%—to $150 billion—in the North Sea alone.

Government and companies recognize the issue. Some governments have set goals of reducing decommissioning costs by 30% or more, and operators are starting to develop plans of action. But few companies have decided on the decommissioning operating model they want to adopt, which means that they have yet to identify the skills they wish to maintain internally, the activities they will outsource, and the network of contractual relationships they will need in order to liquidate their decommissioning liabilities. And even as the industry gears up for a global wave of work that will run for the next several decades, it is still operating with multiple models in parallel. Oil and gas company shareholders and managers—along with taxpayers, who could be on the hook for as much as 80% of the bill—are looking at the prospect of billions of dollars of waste and inefficiency.

Inconsistency Costs

Outside the Gulf of Mexico, offshore decommissioning at the scale the industry is now facing is a relatively new phenomenon. Much of the immediate responsibility falls on operators, but their efforts to develop a plan of attack—whether at the project, basin, or company level—are hampered by multiple factors, including their own lack of experience, regulatory inconsistency and inaction, and uncertainty over the capabilities and expertise of their suppliers. This can lead to inertia because most jurisdictions have set no time frame for decommissioning. For example, in Alberta, the number of inactive onshore wells has been growing at 5% annually for 20 years and now exceeds 90,000. Operators in the province would need to triple their plugging and abandoning (P&A) activity just to stabilize the current inactive well count.

The situation in Alberta and elsewhere gains urgency as old wells and structures deteriorate, their condition and the implications for decommissioning costs become increasingly uncertain, and the global decommissioning challenge grows in size. Companies and governments need to develop coordinated plans of action. But this requires operators to determine the most effective and efficient model for managing a billion-dollar liability, and the situation for each operator in each basin can—and does—vary by player and circumstance. Some will want to outsource as much as possible. A few others may see opportunity in developing specialized expertise so that they can acquire and liquidate assets at the end of life, thus decommissioning them at a lower cost than their current owners. There are plenty of options in between.

Operators must determine the most effective and efficient model for managing a billion-dollar liability.

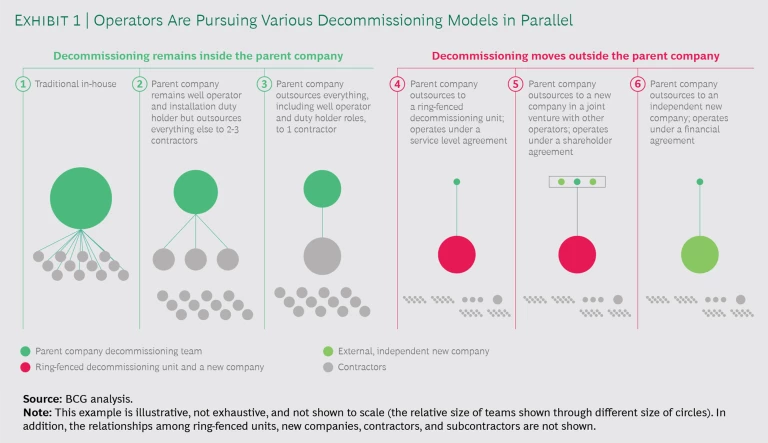

At the moment, we see at least six models emerging. (See Exhibit 1.) The most common involve operators handling well P&A activities while outsourcing activities that require nontraditional exploration and production (E&P) skills, such as heavy lifting and disposal. Some are building full capability internally. Others are outsourcing most activities but developing enough in-house expertise to become an intelligent buyer. Still others are seeking to outsource as much as possible, including the roles of well operator and installation duty holder. And we expect that a few will carve out decommissioning from the business portfolio, housing it in a new business unit or spinning it off as a separate company.

It’s still early days, and all of these models are valid, but the so-far fragmented approach means that industry players are achieving few benefits of scale or standardization across either companies or basins. Continuing to pursue multiple parallel models is likely to lead to inefficiency and waste in the form of:

- Higher-than-necessary abandonment expenses for operators because of a failure to drive down the performance curve.

- Higher team costs from having to build and retain significant, but only intermittently busy, in-house decommissioning teams.

- Wasted time for both operators and suppliers as a result of multiple evaluation and tender processes. Operators are trying to balance known and trusted providers with new entrants from outside the E&P sector: one operator prequalified 40 firms for a platform removal. Suppliers are frustrated by having to participate in multiple tender processes, qualification conversations, and credibility-building exercises with, typically, low or no return as operators pick and choose partners à la carte.

- Inadequate or misplaced investment. Without the stable workflow that comes from an established decommissioning system, suppliers can neither invest seriously in tailored decommissioning assets, people, and solutions nor build experience base and performance track records.

- Lack of specialized expertise. Suppliers often have to balance decommissioning work with traditional development to keep assets and people busy. As a result, they are diluting their advantage of specialization and are reluctant or unable to take on serious portfolio risk or liability within their offerings.

Industry players are not the only ones that are frustrated. Governments and regulators are also concerned because they have made promises about progress, and some are starting to feel scrutiny. In January 2019, for example, a report by the UK’s National Audit Office warned that the expense of offshore decommissioning could far exceed the £24 billion estimate for the total cost to government.

Accelerating Progress Toward a Decommissioning Delivery Model

Decommissioning requires a level of coordination among governments, operators, and contractors—all of which are driven by different incentives. Although operators and contractors play essential roles in defining and executing an effective decommissioning agenda, governments can establish a comprehensive governance framework and support it with strong institutions.

Decommissioning requires a level of coordination among governments, operators, and contractors—all of which are driven by different incentives.

Despite incentives that differ in many ways, players in the private and public sectors have similar interests:

- Enabling the most prudent and efficient use of taxpayer and shareholder funds

- Creating incentives for operators to maximize and continually improve their performance in terms of cost efficiency, safety, and environmental compliance

- Allowing supply chain participants, such as suppliers, to play an active role in developing the solutions and technologies needed in each basin

We have detailed previously a number of the actions that operators, suppliers, and governments need to take to reduce decommissioning expense . The immediate question is, how can players in the private and public sectors accelerate progress? At the moment, operators are still experimenting, and they tend to focus on what’s best for the next asset to be addressed. Few are looking at an entire basin or portfolio. Operators need to make choices about their long-term approach and move in whatever direction they decide. We put the burden for taking the lead on operators—and especially on the big operators in each basin—because we don’t expect most governments to impose regulatory targets and incentives as the US did in the Gulf of Mexico. We also are skeptical of the ability of multiple players—which have their own, sometimes competing, interests—to align around a shared business model. (See “Four Prerequisites for a Decommissioning Ecosystem.”)

FOUR PREREQUISITES FOR A DECOMMISSIONING ECOSYSTEM

FOUR PREREQUISITES FOR A DECOMMISSIONING ECOSYSTEM

Decommissioning needs an ecosystem: a community of operators, suppliers, and government agencies that interact with the common goal of developing an efficient and effective decommissioning system. In our view, companies must meet four prerequisites to create such an ecosystem. If not, the industry is destined to continue with traditional models and pockets of innovation and fail to capture the full potential and scale benefits of newer approaches.

Board and CEO-Level Alignment Between Operators and Contractors

It is difficult to push an operating-model change through layers of managers and technical staff, who may well have reservations about what they are being asked to do and few incentives to accelerate the path to low-cost decommissioning. We have seen fundamental operating-model change only when operators and contractors have aligned at the top and leadership has prioritized the change for senior management. In the past two years, we have seen several major operators partner with technology providers to codevelop their digital capabilities. The company-wide change in operating model that is required by implementing digital ways of working received executive level endorsement.

A Cadre of Specialized and Credible Suppliers

Champions of innovative decommissioning operating models need to know that some suppliers are committed to developing best practices and a competitive offering that supports the operator’s in-house capabilities. Suppliers need to demonstrate their business case, such as saving money for the operator, allowing it to offload risk, or focusing management time elsewhere. They may also need to show commitment by investing in specialized teams, equipment, and processes. Some are already doing so: WellSafe Solutions and Decom Energy in the North Sea are two examples.

A Commitment to Mutual Dependence

Just as new technologies prompted industry players to form long-term partnerships, decommissioning requires durable, close working relationships between operators and suppliers that envision taking risks and reaping benefits together. Operators can guarantee work for suppliers and give them room to test new technologies and techniques. Suppliers can provide cost reliability and an efficient working relationship. Companies share data, planning, and coordination. Both can benefit from obviating time-consuming and expensive qualification and tendering processes. Working together and retaining the same specialized crew and equipment, they can maximize progress up the learning curve.

Flexible Customization Within Specified Standards

Governments and regulators can set targets and standards, but they should then allow the industry to collaborate with other marginal sectors and replicate their critical success factors. For example, large shale producers, such as Chevron, have used a factory model to manage multiple sites (with multiple owners) in concert and take advantage of scale by securing adequate supplies of labor, infrastructure, and materials simultaneously.

Here are the four steps that all operators must take to identify and move toward a consistent and high-performance delivery model.

Step 1: Make a strategic decision on decommissioning and then follow through. At a fundamental level, operators need to decide if they want to make decommissioning a core activity that underpins the way they create value. Few will choose to do so, and most have already made the choice (whether consciously or not) to remain pure E&P players and leave decommissioning to others. But even the decision to outsource has implications for business models, contracting strategies, skills, and workforces. We continue to encounter many companies that have not integrated decommissioning into their long-term business plans. These companies will soon find themselves with assets that are losing money and have no organization and governance capability for cost-efficient decommissioning. For example, they will not be able to commit to multiyear contracts and E&P assurance processes for well P&A and lifting operations.

Step 2: Determine the desired end state for the decommissioning delivery model. Once an operator decides what decommissioning means for its business, it must adapt its delivery model. Four key questions to tackle are:

- Which decommissioning activities will the operator keep in-house and which will it outsource? We’d argue that if companies do not deem decommissioning a core activity, they should consider outsourcing as much as possible to a trusted specialized contractor or contractors.

- What levels of risk and control will the operator entrust to others?

- What decommissioning organization size and capabilities will it build? An outsourcing strategy dictates building just enough in-house capability for the company to be able to act as an intelligent buyer of decommissioning services—but even that still has implications for staffing.

- What capabilities will the operator need from the supply chain?

Companies quickly find that the answers to these four questions are intertwined. Shaping an E&P company’s decommissioning delivery model is far from a simple exercise (a big reason why so little progress has been achieved to date). Each decision must be thought through in the context of the answer to Step 1 and the nature and maturity of the decommissioning ecosystem, particularly the capabilities of potential partners and suppliers, in the basin. In some basins, for example, the ecosystem is not yet well developed, the capabilities in the supply chain are limited, and good contractors are either hard to find or very costly—or both. Distinct options must be clearly defined and ranked. Choices need to be underpinned by a robust assessment of the value likely to be achieved and the tradeoffs to be made.

Step 3: Identify the gaps and the solutions required to fix them. The typical hurdles to achieving the desired end state involve supply chain capability, in-house capability, and the company’s broader business model, organization, governance, processes, and culture.

The largest gaps in supply chain capability tend to relate to the end-to-end delivery of decommissioning projects at scale along with financial strength and the capacity for risk. Operators must take the lead in closing these gaps by selecting a limited number of suppliers with which to codevelop decommissioning capabilities. Suppliers must respond with clear demonstrations of commitment, such as deploying tailored P&A assets. Governments can help by creating the right context and incentives for this type of collaboration.

Unless operators go so far as to carve out decommissioning by creating an external company, they will need to access the technical capabilities and experience that can deliver cost-effective planning, scheduling, and cost estimation, as well as the safe removal of facilities and well P&A. In addition to closing the capability gaps, companies also need to adapt their contracting strategies, organization, governance, standards, and processes and systems to support the new delivery model. How each operator meets these challenges depends on the nature and maturity of its basin’s decommissioning ecosystem and the company’s own starting point.

A few E&P companies may go beyond straightforward supplier relationships and codevelop innovative business models with suppliers for decommissioning at scale. It will take one or more firms to synchronize large blocks of similar decommissioning activity, and to deliver with continuous crews and equipment, in order to achieve the full value of such models.

Step 4: Develop a roadmap. Operators will need a detailed roadmap to bridge these gaps, and they should recognize that doing so will take time. Setting up a specialized decommissioning company could easily take two years. Establishing decommissioning-specific processes alone has taken some specialized suppliers 18 to 24 months.

The roadmap must define the workforce plan for each asset and each activity, including the staffing levels necessary for the decommissioning team and supporting activities, from end-of-life operations to well P&A, structures removal, site remediation, and monitoring. The roadmap should address potential pain points in advance, such as a lack of accountability for decommissioning performance, unstable decommissioning plans, and ineffective handoff from operations to decommissioning teams.

One critical question to ask is, What is the value of the alternative delivery models, and what conditions will need to be met to realize this value? A recent BCG study, carried out in collaboration with a North Sea operator, uncovered the potential to reduce decommissioning costs by 5% to 15% through changes in operating and contracting models.

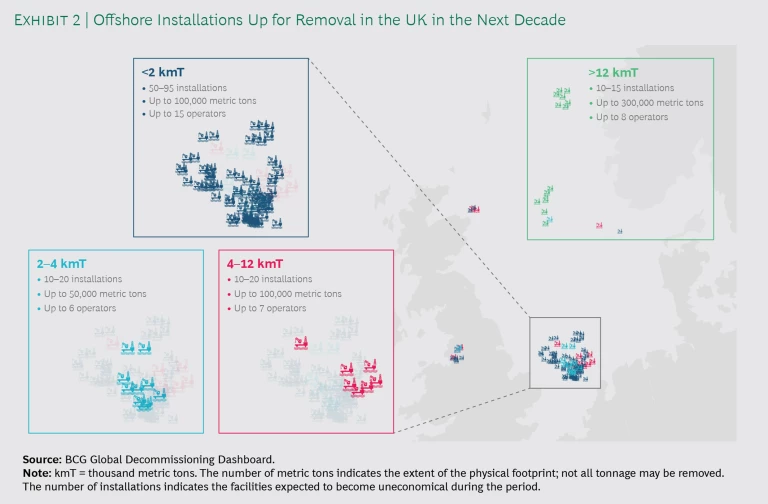

For suppliers, the opportunity is vast. For example, in the next decade, about 80 to 150 offshore installations are expected to become uneconomical in the UK alone. (See Exhibit 2.) A supplier able to tackle a single activity and equipment archetype (such as the removal of topsides weighing less than 2,000 metric tons) could access a large market, in this case up to 100,000 metric tons. To this can potentially be added the removal of the respective substructures and adjacent services. Innovative business models could help suppliers capture a disproportionate share of the decommissioning market through improved cost efficiency and longer-term relationships with operators.

The industry recognizes the decommissioning imperative. But it has yet to translate this recognition into a few replicable and high-performance delivery models. The leaders in each basin need to force the issue with firm decisions on their own decommissioning strategies and then collaborate with their suppliers to build the skills, assets, and business models that put them into action.