If consumers in the Gulf Cooperation Council were feeling uneasy about the future, it would be understandable. The countries are still experiencing the effects of oil price volatility, which led to an economic softening in 2017 and 2018. Although GCC economies are again expanding, overall growth in the region appears likely to remain below 3% this year, according to World Bank estimates.

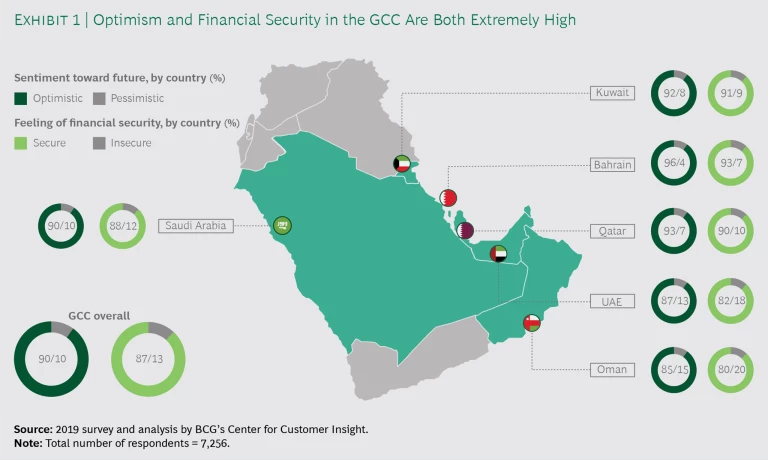

Yet little negativity is detectable among GCC consumers. On the contrary, 90% of people in the region—which consists of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—said they are optimistic about the future, according to a Boston Consulting Group survey. This level of optimism is the highest that BCG has found in any recent consumer survey it has conducted, including studies in Africa, Brazil, and Russia.

The optimism levels in the GCC seem to be a function of the financial security that the residents of these countries feel. Only in Oman and the UAE, which have lower levels of financially secure residents than other GCC countries, does the optimism level dip below 90%. (See Exhibit 1.) But even in these two countries, the proportion of financially secure, optimistic respondents is high by most of the world’s standards.

To provide a few points of comparison from our previous BCG consumer surveys, 86% of Africans are optimistic about the future and 70% of them feel financially secure. In Brazil, the proportion of optimists and those who feel financially secure is 68% and 53%, respectively. In Russia, it’s 55% and 60% .

As the wealthiest region in the Middle East—all six countries fall within the top quartile globally by per capita income—the GCC is increasingly on the radar screen of expansion-minded companies. And it isn’t only the region’s spending power that has gotten these companies’ attention. The GCC also has a young, fast-growing population and internet penetration levels that are comparable to those of the most developed countries in the world. Just about every nation in the GCC, from Saudi Arabia and the UAE with their expansionary fiscal policies to Kuwait with its 97% internet penetration, has something that’s appealing from an economic perspective. If ever a region had the potential to capture the attention of multinational companies, this is it.

Attitudes Toward Shopping

GCC consumers’ feeling of optimism has put them in a spending mood. Of the people participating in our survey, 27% said they expect to increase their spending on products and services in the next 12 months; only 12% anticipate spending less. (About half don’t think they’ll make any change in their purchasing levels.) Among those planning to spend more, food and beverages, nonluxury clothing and shoes, educational services, and out-of-home entertainment are among the most frequently mentioned areas of additional spending.

The survey also reveals that shopping in the GCC has benefits besides satisfying near-term needs—namely, an emotional payoff. In our survey, 79% of GCC residents said that the ability to buy new things makes them happy. That’s well above the 56% of people in developed economies who indicated this and is closer to the prevalence (86%) of this attitude in Africa. In addition, 44% of GCC residents said that they occasionally spend extra money to treat themselves, even when their financial situation is bad. (See “The Who and How of Our GCC Survey.”)

THE WHO AND HOW OF OUR GCC SURVEY

THE WHO AND HOW OF OUR GCC SURVEY

This is the first survey of consumer sentiment that BCG has done in the Gulf Cooperation Council, a region that includes Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

The interviews were conducted in person in January and February 2019, either at a respondent’s home or office or in a public café depending on the participant’s preference. More than 7,000 people participated, split about equally between expatriates and nationals. Some GCC countries have large populations of expatriates, drawn by the region’s economic opportunities. Expatriates, of course, have different attitudes on some topics. Where national origins seem to explain a difference in attitude, we have highlighted that in this report.

The interviews comprised 75 questions and took an average of 40 minutes to complete. Participants were queried on their overall sentiment as well as on their use of digital technology. In addition, the survey explored participants’ attitudes and behaviors with respect to offline shopping, e-commerce, and tourism—three economic segments that are especially important in the GCC.

Respect for Established Brands. The GCC is a brand-aware region. Three-quarters of GCC nationals believe that brands say something about their values and who they are, and the percentage is even higher (83%) among Saudi Arabians. This is one of the areas where we found a significant attitudinal split between nationals and expatriates: only 56% of the region’s expatriate population agrees that brands say something about who they are. Qataris (at 36%) are the least likely GCC citizens to characterize themselves as brand conscious. But even Qataris are well above developed markets in their identification with brands. Only about one of four people in developed markets see their brand selections as saying something about who they are.

The region also demonstrates a strong bandwagon effect regarding brands. That is, 46% of people in the GCC said a friend’s disapproval of a brand, product, or service would probably be enough to stop them from buying it. As a point of comparison, only 18% of people in Russia said they would stop using a brand if someone in their social circle disapproved of it.

GCC consumers trust older brands, with 79% of them saying the brands that have been around the longest are the best. But in a twist, many GCC consumers (46%) also said that they would prefer to use different brands than the ones used by their parents. These seemingly contradictory attitudes suggest that an opportunity exists for brands to reinvent themselves and project newness and dynamism—moving to something that feels more modern without tossing out their legacies.

Factors That Influence Purchasing Decisions. As in all parts of the world where the level of digital connectedness is high, the internet, social media, and online influencers (people seen as experts in a given area) have a big impact on GCC consumers’ buying decisions. The internet is one of the top three buying influences in every country except Oman, with people in Kuwait (92%) and Bahrain (88%) especially likely to turn to it in the course of making a purchase. The two other sources of influence that remain important are recommendations from friends and family (the second most frequent source of influence, right behind the internet) as well as in-store displays and promotions.

One doesn’t want to give the impression that GCC residents are entirely focused on spending. They also do a fair amount of saving, a fact that came through in the survey. (See “The Savings Habits of GCC Consumers.”)

THE SAVINGS HABITS OF GCC CONSUMERS

THE SAVINGS HABITS OF GCC CONSUMERS

With some of the highest average incomes in the world, GCC residents have the means to save. And the survey suggests that they take advantage of it.

Most respondents reported that they save 10% to 25% of their monthly income. This exceeds the official savings reported by most of the region’s governmental agencies. Part of the difference may be explained by the fact that those taking our survey were slightly above the GCC average in their average income levels. Also, our survey, unlike official government surveys, includes expatriates, who set aside large portions of their incomes for repatriation to home countries.

If the self-reporting is accurate, our respondents save considerably more than consumers in the US (10.5%) and Japan (9%). Qatari nationals are at the top of the savings scale in the GCC, according to our survey, with the vast majority of citizens in this nation (the region’s wealthiest on a per capita basis) saying they save 25% to 50% of their income.

Throughout the GCC, the top three reasons for saving are to set aside funds for an emergency, to have a financial cushion, and to be able to take a trip or go on vacation. Education gets a larger share of the savings allocation in the UAE than it does in other GCC countries.

A Slow Start for E-Commerce

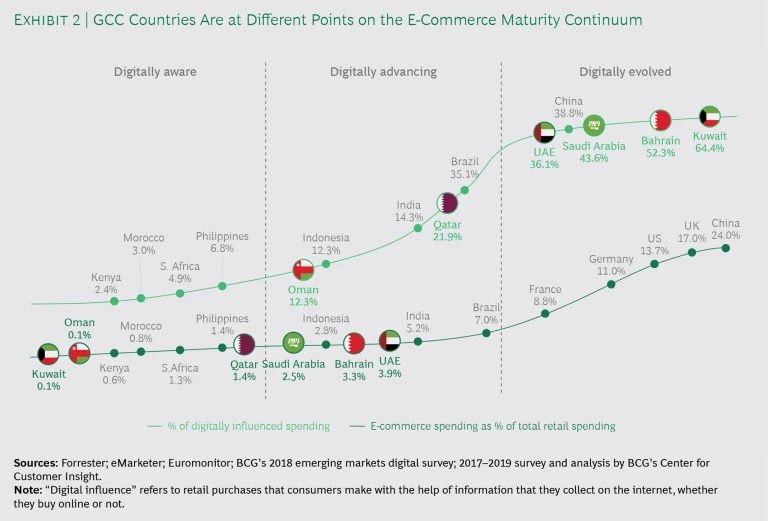

The circumstances would seem to be in place for the GCC to be a hotbed of e-commerce. The levels of internet and mobile technology use among residents, and the region’s per capita incomes, are comparable to and in some cases higher than they are in places where e-commerce levels are already approaching or above 15% (such as the UK and US). Moreover, GCC consumers already make heavy use of online research to inform their offline retail purchases. This is what we refer to as digital influence, and it’s one of two measures of digital maturity that BCG tracks . A high level of digital influence (whether chats with friends, social media postings, search engine inquiries, or something else) is especially common in Kuwait and Bahrain, where it is a factor in half of all the money spent in malls and other offline shopping venues.

The internet’s role in the GCC shopping scene doesn’t stop at influence. More than 70% of GCC consumers have made at least one online purchase in the past 12 months, and half of them plan to increase their online purchases in the next year.

Yet e-commerce still constitutes a very small fraction of overall sales in the GCC—BCG’s second measure of digital maturity. Even in the most active e-commerce country, the UAE, online sales account for only 4% of all retail sales. In Kuwait and Oman, e-commerce hardly exists at all: it accounts for just 0.1% of all retail expenditures.

Although the GCC seems like it should be a hotbed of e-commerce, online shopping constitutes a very small fraction of overall sales in the region.

To consider GCC countries’ state of development in these areas is to recognize the gap they all have between potential (digitally influenced) and realized e-commerce. (See Exhibit 2.) From the perspective of digital influence, four GCC countries fit into the most advanced category that BCG uses: digitally evolved. Three of these countries (Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE) also have e-commerce levels that qualify them as digitally advancing (BCG’s second-most-advanced category). But even these countries have less e-commerce than Brazil and India. Compared with those bigger nations, GCC countries are simply not as well set up for e-commerce development, with only a fraction of the SKUs that larger markets have, more rudimentary last-mile delivery infrastructures, and friction-filled import and customs processes.

Theoretically, product categories with high levels of digital influence should also have high levels of e-commerce. But in the GCC, that tie is apparent only in the air travel and clothing categories. An opportunity exists for other categories—including holiday bookings, mobile phones, and personal-computing devices—to achieve much higher levels of online sales if online retailers offer better presale guarantees and after-sale service. (See Exhibit 3.)

Major Impediments. The survey highlights three impediments to e-commerce in the GCC. The first is payments. About two in every five online purchases in the GCC are paid for via cash on delivery (COD)—and the proportion is considerably higher (62%) among consumers who don’t work. The fact that people in the GCC, given a choice, would prefer to pay in cash rather than using digital alternatives suggests that there’s a low level of trust in the region in online payment methods. It might also reflect consumers’ desire to retain some flexibility if a product arrives and they decide that they don’t like it.

In contrast, higher-income and more experienced internet users (those who have been online for six years or longer) prefer methods other than COD. This finding suggests that online payments will become more routine as time goes on. Indeed, some online sellers, trying to nudge their GCC customers toward the cashless future, have added a surcharge for COD transactions.

The second factor that has hampered e-commerce is dissatisfaction with the experience among online shoppers. The number one source of dissatisfaction regionwide is the difficulty and expense of returning unwanted products. Product availability is another problem—the number of items available online in the GCC is surprisingly small. A final frustration relates to unreliable deliveries. But even if the reasons vary, the result is the same: the consumers who have had these bad experiences said they won’t be doing as much online shopping in the next 12 months as they did in the previous 12.

The third impediment to e-commerce is persuading people who have never shopped online to give it a try. The most common objections to online shopping (cited by roughly 40% of respondents who are cutting back on their online purchases) are a preference for seeing or touching a product before buying it and the sheer pleasure of going out shopping. This comes back to the feeling of happiness that people in the GCC get from shopping.

Other Limiting Factors. Online shopping also has some reputational hurdles to overcome. A not insignificant number of people in the GCC (including four of five in Bahrain) see online shopping as unsafe—something that could put their personal information at risk.

One in five GCC residents also said that too many products sold online are fake or of bad quality. No one wants to buy a cosmetic or food product with unknown ingredients or open a package and realize that the phone they thought they were buying new is actually a used model that the seller has restored.

The early stage of e-commerce in the GCC is also reflected in the absence of a dominant format. Marketplace platforms (such as Amazon and the e-commerce company Noon.com) are the go-to choice for online shoppers in Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. People in Bahrain and Kuwait prefer social media sites like Facebook and Instagram, where they can buy directly from individuals. In Qatar, brand websites (such as nike.com and apple.com) are the first choice of online shoppers. But in none of these countries does the number one format have an insurmountable lead. All the markets are still waiting for a clear direction—waiting, it might be said, for a leader to come along.

The region lacks a dominant format for e-commerce—the GCC markets are still waiting for a leader to come along and provide clear direction.

GCC Tourism: Preferences and Habits

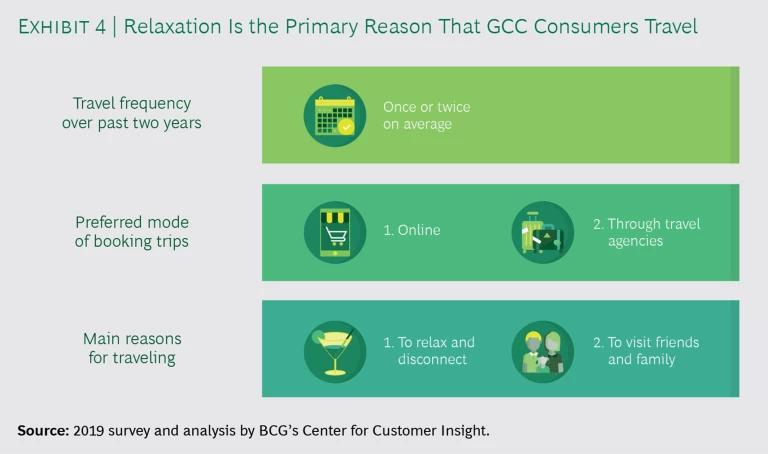

Leisure travel is popular in the GCC, with people taking one trip a year on average. Travel frequency goes up along with income, but even most of the wealthier people in the survey (with household incomes exceeding $8,000 a month) tend to travel once or twice a year, not more.

In every GCC country, the most common reason for traveling is to relax and disconnect. The second most common reason is to visit friends and family. (See Exhibit 4.)

Among expatriate respondents, the reasons are flipped, with visits to friends and family the leading reason for leisure travel. This is not surprising given that most expatriates are in the GCC for work and may have another place, often far away, that they consider home.

Other motivations for traveling apply more to nationals than to expatriates. This includes the interest in discovering a new country or city (a reason given by 58% of nationals but only 31% of expatriates) and the desire to shop (a motivation for half of nationals but less than a third of expatriates).

The Impact of Income on Travel Preferences. The desire to shop and to discover new places went up in our survey along with respondents’ household incomes. Consumers earning more than $8,000 a month were much more likely to cite an interest in shopping as a reason to travel than were those earning less than $2,500 a month. This difference was more pronounced among nationals than expatriates. The survey showed a 20-percentage-point difference between the high-income nationals who said that they travel to shop (56%) and the low-income nationals who indicated that they travel to shop (36%). Among expatriates, the difference was only 11 percentage points (31% to 20%).

When they travel domestically, people in the GCC are often looking to experience their own country’s natural beauty, resorts, and cultural sites. Those attractions appeal to 60%, 44%, and 41%, respectively, of all GCC consumers.

Planning and Booking Trips. Travel planning is one area where GCC consumers’ resistance to online purchasing recedes. In the GCC as a whole, 54% of all consumers book their trips online, with bookings made through travel agencies accounting for a much smaller piece of the pie (25%). Only people in Oman buck the trend and do a majority of their travel planning through agencies (the ratio among Omani residents is a lopsided 2.5 bookings with a travel agent for every one that’s done online). Travel agency bookings are also a bit more common among people who don’t work than among people who do, perhaps because nonworkers have more time to visit a travel agent.

All-inclusive packages—in which flights, hotels, and rental cars are booked in a single transaction—are the default option for trips in the GCC. Two-thirds of respondents said they are likely to opt for such packages when planning a trip, including 25% who went even further and said they are “very likely” to opt for an all-inclusive package. And if the sample is limited to nationals (omitting expatriates), the proportion of those likely to buy an all-inclusive package rises to 75%. Similarly, the proportion jumps to 75% if you restrict the sample to households with monthly incomes above $4,000, suggesting that all-inclusive deals appeal to those who are less price sensitive.

The findings don’t differ much by country—travelers in most GCC countries are interested in all-inclusive deals to about the same extent. But people in Bahrain and Qatar are outliers at the high and low ends, with 45% and 10%, respectively, of respondents saying they are very likely to opt for all-inclusive packages when booking travel.

In the current era of travel, airline and hospitality companies often try to get consumers to pay extra for premium services. Our survey shows that flexible booking is the add-on that the most GCC consumers are likely to buy, followed by excess baggage and exclusive hotel offers (offers that aren’t available outside of the all-inclusive package). These three add-ons are the most popular ones in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. But not every GCC country follows the same pattern. People in Bahrain are more interested in visa processing than they are in exclusive hotel offers. To people in Qatar, flight upgrades trump exclusive hotel deals. Omani residents show the most variation from GCC averages; they put flight upgrades and visa processing on par with excess baggage and far ahead of flexible booking and exclusive hotel offers.

Travel planning is one area where GCC consumers’ resistance to online purchasing recedes.

Preparing for Boom Times

Anybody with a stake in the GCC’s economy can sense the opportunity that’s at hand. Significant changes are happening in the region’s retail and consumer landscape. This is evident in the entertainment and cultural attractions that continue to crop up in countries like Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE, from movie theaters to museums. Expo 2020 in Dubai and the FIFA World Cup two years later in Doha will draw millions of tourists to the region. It is a potential boom time for the region’s tourist industry.

One of the biggest boosts is coming from Saudi Arabia. For the first time in its history, Saudi Arabia is issuing tourist visas. The country is taking steps to turn its rich history, like the ancient archeological site Madain Saleh, into tourist attractions. While a lot of leisure travel occurs within the GCC and between other countries and the Middle East, the change in Saudi Arabia all by itself promises to sharply increase the competition for tourists and their retail spending.

Even the GCC’s slow-developing e-commerce sector seems poised for a breakout. The challenges in the sector, stemming both from structural impediments and from a lack of consumer trust, won’t be overcome right away. But with players such as Amazon and Noon.com ramping up their investments in the GCC, it’s only a matter of time—given the amount of internet and mobile use in the region—before e-commerce levels rise significantly.

Global and local companies are taking note of all this. The fact that consumers in the region, and nationals in particular, are so brand loyal bodes well for companies that can win consumers’ business. Figuring out how to do that—and generally how to tap into the region’s vast potential—will capture the attention of many companies in the coming years.