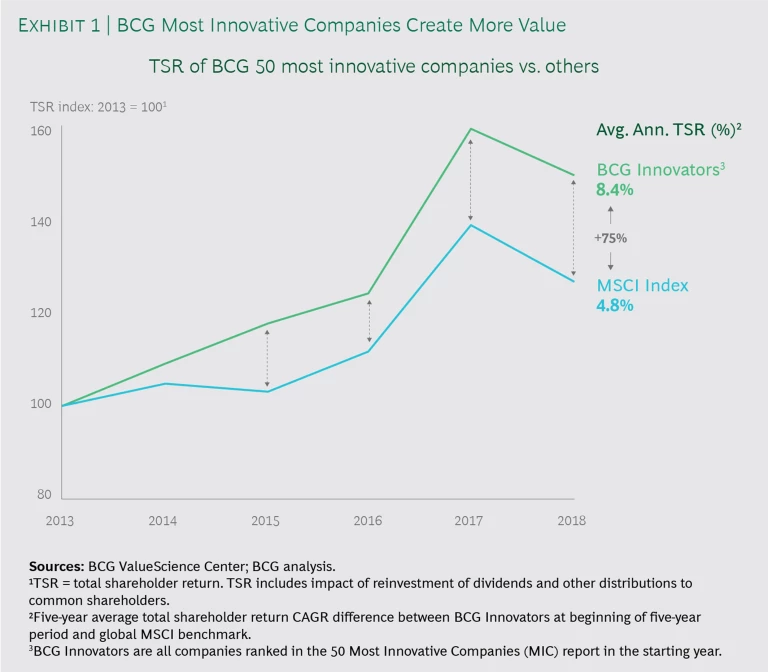

Innovation is more important than ever. Mature markets, shorter product lifecycles, the importance of growth to long-term shareholder value—these all put a premium on the ability to invent new business models, products, services, and processes. Digital technologies both raise the stakes and accelerate the pace by expanding the horizon of the possible. And history shows that innovators outperform others. Innovative companies on average generate annual total shareholder returns that are 3.6 percentage points higher than those of their peers. (See Exhibit 1.)

Still, many companies struggle. In BCG’s most recent survey of global innovation trends and practices, 80% of innovation executives said innovation was a top-three priority at their companies, but only 30% said their organizations were good at it. In our experience, there are four, often interconnected, reasons that innovation programs fail to deliver real results. Each involves a different way in which the innovation journey can break down. Here’s the roster of these pitfalls—and what leading innovators are doing to avoid them.

All Torque, No Traction

Many organizations have plenty of people willing to innovate, but they remain unclear about the company’s innovation ambitions and each unit’s role in achieving those. People therefore work busily on new ideas, but they are not pulling in the same direction. Efforts are mostly incremental and don’t scale. While the wheels spin, getting anyplace is hard. The most ambitious innovators become frustrated and start to think about leaving.

Effective leaders sell the dream: they articulate a vivid image of innovation success.

To escape this trap, effective leaders sell the dream: they articulate a vivid image of innovation success. They anchor their compelling ambition to the corporate strategy, with specific targets for growth and value creation. They then formulate the strategy that will deliver value, and they define what kind of innovator the organization wants to be—consistent with the company’s current and future capabilities. Will it embrace the innovation model of a fast follower, for example, or a different model such as solution builder, leverager, or expander?

But ambition alone is not enough. Effective innovation leaders choose their players, and they clarify the role of each innovation vehicle and what it should contribute to the target portfolio of activities. Given the growing importance of external innovation , these leaders also make clear the key participants’ roles in the broader innovation ecosystem (such as external partners or incubators).

For example, Merck operates at least five innovation vehicles—a venture fund; an innovation center as an accelerator; an open idea challenge with heavy employee involvement that is available also to external parties; virtual training academies; and a think tank covering adjacencies. Crucially, Merck is clear about each vehicle’s role within the company’s wider innovation ambition. Headquarters-level units take charge of “between and beyond” innovations (those reaching beyond the core or immediate adjacencies), while business- unit-level entities oversee innovations that are close to their core. Microsoft uses what it calls “power metrics”—nonfinancial customer-centric indicators of success over the next few years—to link innovation ambition and company purpose and to encourage more experimentation, collaboration, and customer orientation.

Abstraction, No Action

Other companies struggle with a different challenge. Strategies are too high level or inward-looking, or they fail to incorporate a rich perspective on the changing economic and societal shifts that shape customer needs. What’s more, such strategies are often not linked to customer-centric idea generation taking place in the broader organization. There’s a lot of high-minded talk about innovation, but it never leaves the “ivory tower.”

Great innovators are clear about where they choose to compete. They start by staking the ground—defining the domains and the most attractive market spaces in which they intend to innovate. The domains are often a mix of customer-facing “vertical” areas as well as capability-centric “horizontal” areas in which the company decides to focus its innovation efforts. Company leaders can ask two questions to help achieve a sharp view of a company’s innovation domains: What is our view about future sources of value for customers? And what are we doing that is deliberately contrary to the industry consensus? Daimler defines four customer-centric innovation domains, or centers of focus, each with the “potential to transform the industry,” and summarizes them in the company’s CASE roadmap (connected, autonomous, shared, and electric).

New ideas often arise at the intersections of disciplines, or when people with different perspectives look at the same problem.

To gain advantaged insight into customers and the competitive environment, leaders need to broaden how they think about new products, services, and markets. New ideas often arise at the intersections of disciplines, or when people with different perspectives look at the same problem. Teams should embrace art and science, taking a cross-disciplinary approach to mapping opportunities. In our experience, the most effective teams combine creative or human-centric approaches with a healthy dose of analytical thinking, evaluating market and technology trends through innovation analytics—mining vast unstructured datasets, such as patents, academic publications, venture financing, and social media to reveal new opportunities and risks.

Lego uses techniques such as ethnographic research to better understand how customers view and interact with its products—and with other companies—to provide input for ideation. Meanwhile, Spanish energy company Naturgy has established a technology observatory to help it track and monitor new technological advances, foster partnerships with tech players and universities for better access to proprietary data and insights, and build tools to expand access to and accelerate technical-knowledge sharing. It also partners with networks of startups and other businesses to ensure it stays close to the pulse of the market.

Stuck in the Lab

Some organizations develop lots of ideas—but far too few take flight and make a material impact on performance. Often the issue is a lack of both speed and rigor in idea validation, incubation, and acceleration. Companies pursue mediocre ideas for too long, misallocate resources, and are unable to see (and therefore fund) the good ideas that could actually scale.

Adopting elements of agile ways of working and culture can help. Leading innovators empower cross-functional teams with shared goals to discover and pursue customer-centered growth opportunities—and then work in sprints to create, launch, and learn from minimum viable products (MVPs) in the real world. By failing, failing again, and winning, they empower teams to learn through real-world experiments and maximize for outcomes, not output. Of course, companies using agile methods also need to channel the chaos by defining clear guardrails and high-level direction—and give teams the freedom to create within those limits. Such alignment unleashes the power of autonomy .

Agile puts a priority on speed to market. Teams are free to test MVPs, watch them fail, learn, and move on quickly. In what was once the domain of digital startups, today even traditional manufacturing companies use market-driven product development and launch processes that operate in short phases—which allows them to reprioritize and iterate quickly, based on market-validated KPIs.

To solve for rigor, even large tech companies such as Amazon and Google that are known for their innovative cultures use a guiding structure of governance and process. Both companies encourage risk taking, but they also have stringent capital controls, resource-allocation mechanisms, and clear processes in place to guide projects or kill them.

Amazon and Google encourage risk taking but within a guiding structure of governance and process.

Autoimmune Reaction

Past performance does not guarantee future results. This is nowhere as true as in innovation. As is well-known, large and successful entities are often very effective at starving their emergent offspring. Whether new ventures are delayed by corporate policies, watered down by process, kept on a short leash by internal “customer owners,” or just relegated to organizational purgatory, the result is the same.

To get around this pitfall, top companies lead the transition from the old to the new by managing innovation programs transparently and with discipline, regularly assessing progress and moving quickly to dismantle internal impediments to promising ideas. Some employ dedicated CEO funds and SWAT teams to clear the pathways. At the same time, they are also quick to kill ideas that have no road to success (even if they’re a senior executive’s favorite project) and shift resources to those that do. And they build to scale, by investing in the capabilities needed to support the rapid ramping up of new innovations that have demonstrated a strong product-market fit. The brewer Carlsberg regularly rebalances its product development portfolio to ensure a healthy mix of projects within as well as outside the core, and management regularly shifts capital toward the most high-potential and disruptive projects.

Top companies lead the transition from old to new by managing innovation programs transparently and with discipline.

Leading innovators in markets with short, technology-driven product cycles recognize that the future depends on their continued ability to develop new products and businesses. Cisco trains its executives in the key elements of product development through an intensive 16-week course that focuses on collaboration and product management. The program has gained significant status in the organization, and aspiring leaders vie to participate. That’s how companies raise the internal status of product management and build it into its key talent pipeline for future executives. In fact, we can safely predict that in the future, more C-level executives will have a strong track record in successful product management.

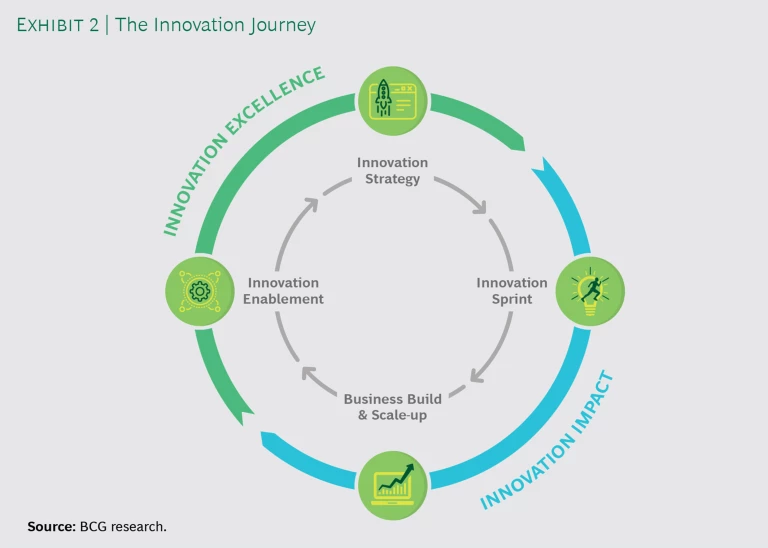

Managing the Journey

Leading companies see innovation as a journey that needs to be managed systematically, on multiple dimensions, to drive excellence and impact. (See Exhibit 2.) Innovation strategy , regularly reviewed, sets direction and brings any disruption to the surface. Successive innovation sprints provide the opportunity to “test and learn” from failure and MVPs. Business build and scale up maximize the returns on the most promising inventions. And innovation enablement ensures that companies have the right capabilities to keep up with changing markets.

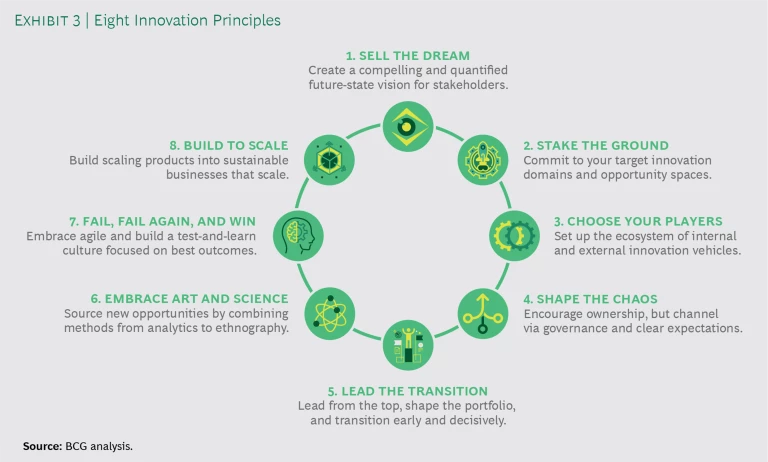

BCG’s eight innovation principles keep the journey moving. (See Exhibit 3.) Each principle on its own might seem easy to implement. Indeed, many innovators follow some—but rarely all—in a best-in-class fashion, since all take time to develop and implement. Therein, often, lies the crux of failure. Top innovators understand that the journey never ends—the point is to keep moving forward, reaping the rewards as you go.