For the United States’ agribusiness sector , federal policy changes over the past few years have been a mixed blessing. Lower taxes and relaxed regulation have made business easier to conduct. But for many, these gains have been more than offset by falling prices due to trade wars that have flared up and lingered on multiple fronts. The price of US soybeans, for example, was at its lowest level in a decade as of September 2019, down nearly 20% since March 2018. That is when the US began sharply hiking tariffs on a wide range of goods imported from China and on steel and aluminum from many other nations. China, the biggest customer for US soy, responded with higher tariffs on US goods, targeting farm products in particular. Other nations hit by the US metals tariffs also retaliated by slapping tariffs on US agricultural goods.

The growing risk now is that much of the market share abroad that US agribusiness is losing to foreign competitors will be hard, if not impossible, to win back.

The growing risk now is that much of the market share abroad that US agribusiness is losing to foreign competitors will be hard, if not impossible, to win back —even if current trade conflicts are resolved to the US government’s satisfaction. Growers in Australia, Brazil, New Zealand, Russia, and other nations are rushing to replace US suppliers of soy, beef, wheat, and other foodstuffs affected by retaliatory tariffs from the US’s trading partners.

At the same time, the US’s withdrawal from previous trade treaties—together with the difficulty it has had in concluding new, comprehensive agreements—has put the nation’s agribusinesses at a big competitive disadvantage in key markets. After the US pulled out of the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, for example, the other member states struck a new deal among themselves that will give major food exporters such as Canada, Mexico, Australia, and New Zealand privileged access in Japan, a critical US market. And while US negotiations with the EU over a new free-trade pact have crawled along, Canada and Mercosur—a group of Latin American nations that includes Brazil and Argentina—have concluded agreements with the EU to give their suppliers an edge over US exporters in that important market.

The longer the trade wars drag on and the uncertainty over US trade policy persists, the more time rivals will have to build the production capacity, distribution infrastructure, and deep-rooted relationships with importers they will need to erode the competitive advantage that US suppliers have built over decades.

Of course, supply relationships in the food trade are not made and broken overnight. It takes years for importers to trust that a foreign crop and protein processor can deliver products on time, even during poor harvests, and that its goods will meet their country’s quality and regulatory standards. In addition, particularly with regard to fresh, ready-to-consume foods such as meats and produce, suppliers often provide logistical and other support that would be costly for an importer to handle on its own. As a result, diversifying to other suppliers or switching to another source entirely can carry substantial risk and cost.

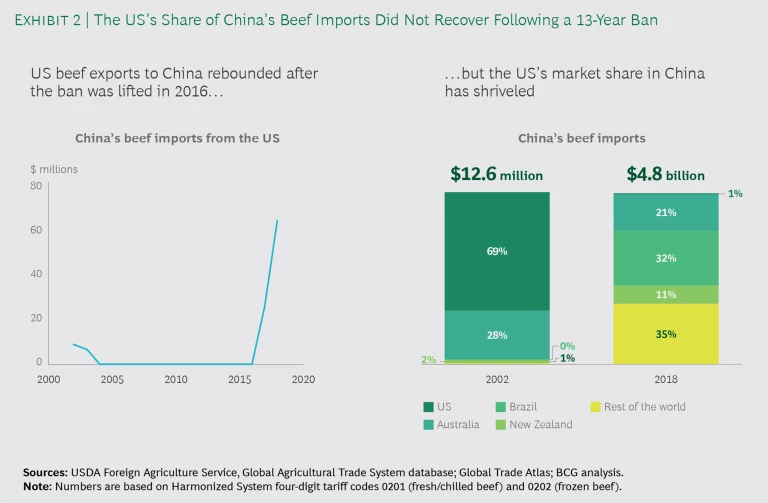

The threat that US agribusinesses will permanently lose foreign market share is not merely theoretical. In previous trade scuffles, such as one with China involving beef, the US has not regained lost share. By making US crops and foodstuffs more expensive than alternatives, high tariffs lower the cost to importers of diversification. And the less faith importers have in the US as a stable supplier, in view of the potential for future trade conflicts, the more necessary it becomes for them to hedge and further diversify. Over time, importers could completely unwind complex relationships with US suppliers.

Finding meaningful alternative export markets will be difficult for US growers and food processors, owing to regulatory hurdles, protectionist barriers, and US trade conflicts. As it becomes increasingly apparent that the trade environment is unlikely to return to the old status quo in the foreseeable future, actors along the entire US agricultural value chain should begin developing strategies for dealing with the new normal. Growers should evaluate options to diversify toward crops and meats that depend less on export markets. Suppliers of farm inputs and crop and protein processors should search for new markets. And downstream food producers should make their supply chains more flexible so that they can quickly adapt to changes in the trade landscape.

Growers should evaluate options to diversify toward crops and meats that depend less on export markets.

Assessing the Fallout So Far

The negative impact of trade conflicts has clearly contributed to the US farm sector’s woes. Overall, US agricultural exports increased by only 1% in 2018, to $140 billion, compared with a 3% increase in 2017; and they were down 5% year-on-year during the first seven months of 2019. Exports of all agricultural and agriculture-related products, including fish, animal feed, and biofuels, fell by 6% during the first seven months. The knock-on effects have rippled through the entire US agricultural supply chain, including suppliers of inputs such as farming equipment.

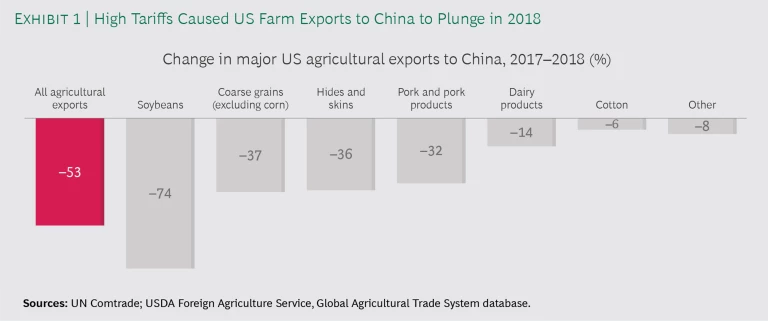

Diminishing exports to China, the largest foreign market for US farmers aside from Canada, have been the biggest factor. In 2017, China bought $19.5 billion in US agricultural products, accounting for 14% of farm exports. In July 2018, China slapped a 25% duty on a range of US agricultural products after the US imposed similarly high tariffs on a long list of Chinese imports. As a result, US agricultural exports to China fell by 53% in 2018, and exports for the first seven months of 2019 were down another 8%. (See Exhibit 1.)

This data masks more severe economic damage to growers of crops that depend heavily on export markets, particularly China. In 2018, US soybean exports to China plunged from $12.3 billion to $3.1 billion, a drop of 74%; cotton exports, which China hit with a 25% tariff, fell by 6% in 2018 and were down 35% year-on-year in the first half of 2019. US exports to China of coarse grains—primarily sorghum—fell by 37% in 2018. US exports of hides, pork, and dairy products have shrunk, too. Although factors such as weather, the global macroeconomic environment, and crop yields also influence prices and demand, the trade conflicts are clearly a significant contributor. Given these headwinds, the US risks losing long-term market share to its competitors in one of its largest and most profitable markets.

Moreover, US exports have been declining at a time when China has been selectively easing its food self-sufficiency strategy. China has recently begun to import more beef, pork, and poultry, for example, albeit still at relatively low volumes. The trend should grow as China’s huge middle class expands and adopts a more protein-rich diet, and as the nation’s scarce land and water resources reach their limits.

There is a chance, of course, that the US and China will strike a deal in the near term. In late 2018, in fact, the two sides seemed to be nearing a truce in which China would agree to substantially increase its purchases of US goods, including agricultural products, to lower the bilateral trade deficit. But talks broke down, and the trade war escalated. Reaching a deal that returned trade policy to the status quo ante would also likely require resolution of other complex disputes, such as over technology trade and market access for US services. Even if the US and China do reach a deal, China will likely keep its supply options open, and US agriculture imports will remain a prime target for retaliation in any future trade conflict.

Even if the US and China do reach a deal, US agriculture imports will remain a prime target for retaliation in any future trade conflict.

Competing nations have already taken steps to profit from the situation. China has increased its purchases of wheat and soybeans from Russia, which hopes to take advantage of its overland trade routes to double its agricultural exports to China over the next five years. Australia and Brazil significantly increased their share of China’s cotton market in the first six months following the tariff increase, while the share of US imports fell from 45% to 11%, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

After an outbreak of African swine fever forced China to slaughter nearly 200 million hogs, Brazil ramped up its pork exports and is moving to authorize dozens of new meat-processing facilities. Although poor weather has slowed Brazil’s ability to seize share in soybeans, it has been gradually displacing the US in China over the past decade and is now that nation’s top soybean supplier.

As other nations’ exports grow, so will their ability to become reliable high-volume suppliers to China. They will plant more land with crops meeting Chinese regulatory specifications, improve quality control, develop distribution and transportation infrastructure, win acceptance among consumers, and deepen relationships with importers.

On several previous occasions, US trade setbacks in China have resulted in permanent loss of market share. In 2003, for example, China banned all US beef after some cattle in Washington State were found to have contracted bovine spongiform encephalopathy—mad cow disease. In 2002, the year before the ban, the US supplied more than half of China’s beef imports. Subsequently, Brazil, Australia, and New Zealand seized most of the US share. China finally lifted the ban in 2017, but in mid-2018 China imposed retaliatory tariffs on US beef. US producers’ share of China’s beef imports fell to 1% by the end of 2018. (See Exhibit 2.)

In theory, even if the US permanently loses Chinese market share in key crops such as soybeans and cotton, it remains in a relatively strong position to compete in other agricultural segments. But in reality, opportunities are limited. China controls food imports through quota systems, various sanitary and phytosanitary requirements, long regulatory approval processes for bio-engineered crops, subsidies to domestic farmers, and other means. China is trying to import as little poultry and pork as possible, and it has remained nearly self-sufficient in corn, wheat, and rice—staple crops that the government views as essential to the country’s food security.

Challenges to Finding Alternative Markets

There are, of course, growth markets in places around the world other than China. Under a recent agreement with the EU, the US will be able to triple its duty-free beef exports over the next seven years, to $420 million annually. US exports of beef, corn, fresh fruits, and other agricultural products to South Korea have been increasing rapidly as a result of the US-Korea Trade Agreement, which went into effect in 2012.

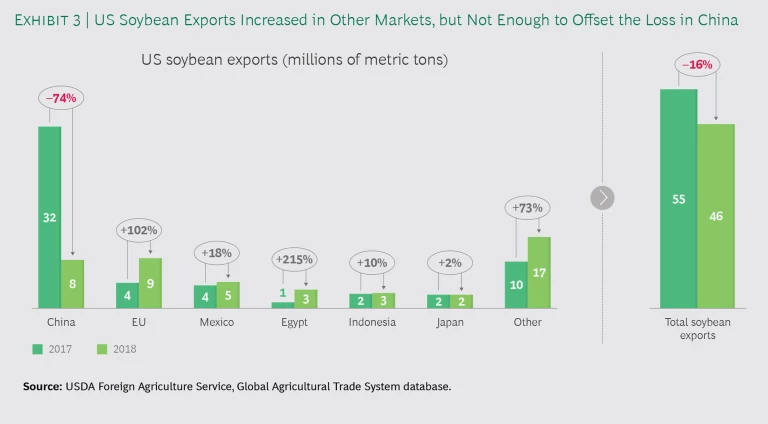

But markets capable of fully replacing China, and new arrangements such as the recent one on beef with the EU, have been hard to find. Although the US increased its shipments of soybeans to other countries in 2018, for example, the overall reduction in US soybean exports of 24 million metric tons suggests that these markets don’t come close to matching China. (See Exhibit 3.)

A number of factors limit export opportunities in major global markets. Some nations set quotas to limit low-tariff imports: Brazil does so for wheat, and Japan for rice. Other countries restrict imports of US crops and meats in response to pest or disease outbreaks—in some cases, longer than necessary, US suppliers contend. Regulations such as those governing genetic modification and the use of growth promoters also make it more difficult, time-consuming, or expensive for US farmers to sell crops and meat products in the EU, Russia, China, and other markets. Bioengineered foods, if approved at all, require long regulatory approval processes that exporters complain are neither transparent nor science based.

A Tougher Trade Climate in Existing Markets

Shifting US policy positions have made it even harder to compete in US agribusiness’s most important existing markets. The country’s trade relationship with Mexico and Canada—the two biggest US agricultural markets in 2018 and important customers of bulk corn, poultry, and wheat—remains uncertain. The United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, designed to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement, would preserve low-tariff trade in farm goods. But Congress has yet to ratify it. Meanwhile, Canada has raised tariffs on US meat and dairy products in retaliation for higher US tariffs on steel and aluminum. The US has threatened to hike tariffs on Mexican exports if Mexico fails to reduce illegal emigration. If the US decides to proceed with these penalties, Mexico will likely respond against US agricultural goods.

The US withdrawal from the TPP has contributed to putting US agribusinesses in a weaker competitive position in major Asian and Latin American markets, too. The US International Trade Commission estimated in 2016 that the original 12-nation trade deal, which the US signed but did not ratify that year, would have boosted US agricultural exports by nearly 3%, or $7.2 billion a year, by 2032. In particular, the TPP would have improved access to Japan, whose tariffs on agriculture products still average 13%. With China’s share of US agricultural exports dropping from 20% in 2017 to 7% in 2018, Japan has become an even more strategic market.

After the US pullout from the TPP in January 2017, the remaining 11 nations concluded the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which came into force this year. Japan has promised to slash its beef tariff from 38.5% to only 9% by 2032 for CPTPP members, which include the major suppliers Australia, Canada, Mexico, and New Zealand. Meanwhile, Japan still has in place a 38.5% tariff for US beef, although a recently announced trade agreement between the US and Japan calls for a phased reduction of tariffs on US beef and other agricultural products. According to a fact sheet released by the Office of the US Trade Representative in September 2019, “When the agreement is implemented by Japan, American farmers and ranchers will have the same advantage as CPTPP countries selling into the Japanese market.” The new deal would also enhance market access for US agricultural goods such as grain, horticultural products, dairy, and other meat products through the reduction or elimination of tariffs. The deal awaits ratification by Japan’s parliament this fall, however, and US exporters may be unable to retake lost market share even after a deal is implemented.

While US trade negotiations remain stuck on several fronts, major agricultural competitors have been winning greater access to key markets. Australia and New Zealand have been negotiating new agreements with China, the EU, India, and other nations. The EU and Canada agreed in September 2017 to eliminate tariffs on 98% of the products they trade, including fruit, nuts, and oil seeds. A new agreement between the EU and Mercosur, if ratified by the EU Parliament, would, among other things, allow Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay to export orange juice, fish, vegetable oils, and some fruits to the EU duty free.

The US withdrawal from the TPP has contributed to putting US agribusinesses in a weaker competitive position in major Asian and Latin American markets.

The Implications for US Agriculture

Until trade conflicts are resolved and stability returns to international markets, players in every segment of the US agricultural supply chain—farm input suppliers, growers, crop and protein processors, and downstream food producers—face difficult options.

Sustained, record-low prices may eventually force many growers out of the market, which will have a knock-on effect for input suppliers.

Farm Input Suppliers. Thus far, most growers have continued to produce despite earning low profits over the past five years. Consequently, the US market for inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and farm equipment has held up until recently. But sustained, record-low prices will probably eventually force many growers out of the market, and this is having a knock-on effect for input suppliers. Eroding US market share abroad will force them to find other foreign markets and other uses for their products. It could also force input suppliers to start diversifying to sectors that are less impacted by trade wars, or to cut production.

Growers. The growers that were hit hardest by low commodity prices and lost export market share are likely to feel the impact for years to come. While this may not always be possible, US farmers in export-dependent sectors should look to diversify to crops that are less sensitive to trade. For US livestock producers, the impact of trade wars is mixed. On the one hand, prices for corn, soy, and other feed are lower, and meat prices have generally held up well so far. Exports account for a relatively small portion of US beef production, and China has continued to import pork due to voracious consumer demand and low domestic supply following the African swine fever outbreak. But over time, as the trade wars persist, they will be hit, too, as foreign competitors establish themselves in export markets and US share erodes. Both farmers and breeders should recognize that current market dynamics will continue and that exports will not substantially rebound after a particular trade war is resolved. With that in mind, they should adapt their planting and breeding strategies to the new normal.

Crop and Protein Processors. Although processors have generally been able to capitalize on falling US commodity prices, the volatility and the uncertainty of US trade policy are likely to have a serious impact over time on their ability to do business. Crop and protein processors should assess the impact of the new trade dynamics on both their revenues and their costs. They should consider diversifying away from key high-profile trade partners targeted by the US and seek to develop inroads into smaller, less conspicuous growth markets around the world. Processors can also build flexibility into their supply chains, and thereby make it easier to adapt to rapid changes in the trade environment, by shifting to other sources of supply. More flexible supply chains will also help processors adjust more quickly to disruptions such as extreme weather and pest infestations that could become more frequent and severe as a result of climate change.

Downstream Food Producers. Export markets have become more important for many US manufacturers of food products, as consumers at home reduce their consumption of many processed and sugary foods. Downstream food producers currently benefit from sustained low commodity prices. But they face similar challenges in export markets over issues such as health and bioengineering standards. Regulators in nations engaged in trade disputes with the US could apply more scrutiny to consumer-ready foods that contain US-produced ingredients. Food producers, therefore, should make their supply chains more flexible so that they can quickly switch to different suppliers as the trade environment continues to change.

Owing to sensitivities over food safety and concerns over the precarious livelihoods of domestic farmers, global agricultural trade has always been contentious. After decades of often-tortuous negotiation, however, the world seemed to be moving toward increasingly free global trade and more stable rules. It may be natural to assume that the status quo will return once the trade disputes that the US is currently embroiled in are settled. However, the longer these trade wars drag on and future policy remains unpredictable, the more likely it becomes that uncertainty will be a fact of economic life for the foreseeable future. It is time for all players across the US agricultural supply chain to develop strategies for adapting to the new normal.