Hydrogen has great promise—but not in the way the most vocal boosters would have you think. Low-carbon hydrogen and associated synthetic fuels will be the key to decarbonizing large sectors of the global economy, making them a critical component in The Economic Case for Combating Climate Change.

But alongside this very real potential is some dangerous hype. Companies and taxpayers risk burning billions to fulfill grand visions of what is often called “The Hydrogen Economy,” the widespread deployment of hydrogen across the energy landscape as the central driver of decarbonization—including in areas where it does not make financial sense. If companies and governments do not become strategic about low-carbon hydrogen, they will waste large sums of money and could make ambitious climate goals even harder to achieve.

If companies and governments do not become strategic about low-carbon hydrogen, they will waste large sums of money and could make ambitious climate goals even harder to achieve.

To unleash the massive potential of this highly versatile and potentially zero-emissions energy carrier, companies and governments must both step up. Companies need to focus their hydrogen investments on use cases where cheaper technologies are not suited and where low-carbon hydrogen can be deployed at scale using existing infrastructure. For their part, governments need to develop a regulatory regime that encourages the deployment of low-carbon hydrogen at scale and in the right areas.

On the basis of BCG’s proprietary H2 cost model and our experience evaluating hundreds of opportunities, we have identified the most promising applications for low-carbon hydrogen over the next decade: industrial processes such as ammonia, steel, and chemical manufacturing, and, potentially, heavy transportation.

If companies and governments get it right, the market for low-carbon hydrogen and associated synthetic fuels could reach $1 trillion by the middle of this century—a clear move from hype to reality.

Applying Low-Carbon Hydrogen at Scale

As an energy carrier, hydrogen has inherent advantages—and disadvantages. On the plus side, it is versatile: hydrogen can combust with oxygen to produce heat, as diesel and gasoline do, it can react in a fuel cell to produce emissions-free electricity, and it can be used directly in chemical processes. But it has some considerable liabilities: Hydrogen is a tiny molecule that can be difficult to contain, it has a lower energy density than carbon-based fuels, and it is relatively expensive to transport and store. Low-carbon hydrogen is also costly to produce given the lack of maturity and scale of the two technologies currently available: Blue H2 and Green H2. (See “The Basics of Hydrogen.”)

The Basics of Hydrogen

The Basics of Hydrogen

Hydrogen can be produced and deployed in various ways. When it comes to production, there are three technologies:

- Black H2. Produced through steam reforming of natural gas or mineral oil, which results in the release of CO2into the atmosphere. This is currently the dominant and most cost-effective production method.

- Blue H2. Produced via steam reforming, but with the capture of 80% to 90% of the CO2emissions produced. That CO2is compressed or liquefied, then transported and stored.

- Green H2. Renewable energy is used to power water electrolysis—which splits H2O into hydrogen and oxygen—a process that generates zero carbon emissions.

Hydrogen can play a role in a variety of conversion processes:

- Feedstock in Chemical Chains. Hydrogen is a component in the creation of products such as plastics and fertilizers

- Fuel in Direct Combustion. Hydrogen can be used in simple combustion to create heat, motion, and eventually electricity, with no carbon emissions.

- Fuel in Hydrogen Fuel Cells. A hydrogen fuel cell is an electrochemical device converting hydrogen and oxygen into electricity and water, with no emissions. Fuel cells can be used in stationary devices or in vehicles.

- Component in Synthetic Fuels. Like petrol and diesel, synthetic fuels are hydrocarbons. But while fossil hydrocarbons are a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions, synthetic fuels are produced from non-fossil carbon, such as carbon from biomass and biogas plants, or the air, and low-carbon hydrogen—leading to low or zero net greenhouse gas emissions.

For low-carbon hydrogen to overcome those disadvantages, players must identify applications for which material hydrogen demand will justify investments in large production facilities and infrastructure (and, in the case of Blue H2, in large CO2 logistics and storage infrastructure). And they must steer clear of applications for which low-carbon hydrogen is unlikely to become cost competitive. The latter category includes use in passenger cars, heating, and power generation.

Thanks to their higher round-trip energy efficiency and their ability to leverage established infrastructure, battery-electric cars have developed a cost advantage in individual mobility, which fuel cell vehicles are unlikely to achieve. As a result, hydrogen is likely to remain a niche technology for use in passenger cars. In space heating and warm water generation, a wide range of potentially low-carbon technologies, such as electric heaters, heat pumps, solar thermal, biomass, and green district heating, will most likely remain much cheaper than low-carbon hydrogen. Finally, hydrogen is arguably one of the least cost-effective power-generating options available today. This is true even if one were to take the often-touted approach of setting up an electrolyzer to run only when there is excess renewable—and therefore free—power.

It is important to note that while low-carbon hydrogen is at an inherent disadvantage in such uses, these applications might be viable in certain countries. Countries that stick with gaseous heating systems, for example, may decide to adopt low-carbon-hydrogen blends of gas in order to limit emissions.

The large-scale use of low-carbon hydrogen will be attractive primarily in applications where few other viable decarbonization options exist and where technology and infrastructure barriers are manageable. Over the next decade, we see two major uses: industrial processes and heavy transport.

In markets where there’s already solid demand for hydrogen, the switch to low-carbon hydrogen would be relatively straightforward.

Industrial Processes. The industrial uses of low-carbon hydrogen are among the most promising, for several reasons. First, Black H2 is already used as an input in the production of, among other things, ammonia and methanol and in petroleum refineries for hydrocracking and hydrotreating. As there is already solid demand for hydrogen in these markets, the switch to low-carbon hydrogen would be relatively straightforward, requiring only advances in the production of hydrogen itself. Second, consumption in these markets is concentrated among a number of large end users clustered in industrial areas, limiting the need for investment in new hydrogen storage and transport infrastructure. Third, most industrial process companies run large capital investment programs to replace and upgrade existing hydrogen production facilities—and such an investment cycle provides the opportunity to decarbonize feedstock. For similar reasons, low-carbon hydrogen has the potential to decarbonize steel production, although that would require substantial reinvestments in steel production facilities.

The potential scale of industrial applications is massive: if all current Black H2 consumption globally were replaced with Green H2, the amount of renewable power required would be roughly equivalent to the total amount of power currently generated in the European Union annually (about 3,500 TWh).

Heavy Transport. Curbing carbon emissions from heavy transportation—land, sea, and air—is one of the greatest decarbonization challenges we face.

For heavy road transport, low-carbon hydrogen in combination with fuel cells could evolve as a viable application in the next decade. In an area where range matters greatly, compressed hydrogen has the advantage of higher energy density than lithium batteries (but lower than diesel). Successful deployment will depend on significant advances in the cost and efficiency of fuel cells as well as the large-scale development of a fueling and distribution infrastructure along main transportation arteries. The outlook for fuel cell trucks will also hinge in part on an unpredictable factor: a major leap in the range and charging speed of electric trucks would severely limit hydrogen’s competitiveness in that application.

For air and sea transport, hydrogen-based synthetic fuels hold considerable promise, but on a longer time horizon (beyond 2030). Although the production of such carbon-neutral fuels is expensive, they can be used in a normal combustion engine or turbine and could therefore become a viable replacement for gasoline and diesel in high-emission applications like aviation and ocean shipping. Synthetic fuels will compete mostly with advanced biofuels, such as fuel from blue algae or organic waste, which are still in the early stages of commercial development.

Uncertainty—and Major Opportunity. While the most attractive prospective applications for low-carbon hydrogen are in industrial processes and heavy transport, the range of potential uses is wide, and hydrogen technology continues to advance. Companies active in the field, such as manufacturers of hydrogen equipment, utilities, and industrial companies that can use hydrogen in their operations, should monitor the market closely. Given how early we are in the development of the low-carbon hydrogen market, regulatory developments and technological advances could quickly lead to opportunities to deploy hydrogen in other areas.

But even if low-carbon hydrogen’s use is concentrated in industrial processes and heavy transport, the potential is enormous. Our modeling shows that if low-carbon hydrogen is deployed in the most appropriate applications and if global emissions are in line with the 2°C Paris targets (a big “if”), the global market for low-carbon hydrogen and hydrogen-based synthetic fuels could hit $1 trillion by 2050.

Even if low-carbon hydrogen’s use is concentrated in industrial processes and heavy transport, the potential is enormous.

Paths to Cost-Effective, Low-Carbon Hydrogen

Identifying the right uses for low-carbon hydrogen means little if there is no reliable, cost-effective means of production. To provide insight on how that can be achieved, we modeled and identified what it requires to make both Green and Blue H2 cost competitive. While this will not be easy to achieve and will require regulatory help (including an effective carbon price), we see good news: there is a clear path to making both competitive with Black H2.

Getting the Scale Equation Right. Both Green and Blue H2 face challenges and require different levels of scale to be competitive.

While Green H2 can be produced at zero emissions, the production process today is not cost efficient, as equipment is subscale and operating costs are high for most configurations. Cost-efficient operations depend on two developments:

- Electrolyzer technology needs to mature, and unit sizes need to increase to 100 MW to 300 MW units, compared with the typical 5 MW to 10 MW units deployed today. Such a development would allow for electrolyzer cost reductions of more than 50% (to below 500 €/kWel for installed systems) and increase efficiency (the amount of power required to produce a unit of H2) by more than 5 percentage points, to over 70%.

- Hydrogen production units should operate with a renewable power configuration that allows high electrolyzer utilization—roughly 5,000 hours a year or more.

Ultimately, Green H2 production facilities that meet the requirements outlined here will be at a scale to reduce annual CO2 emissions by several hundred thousand tons.

Blue H2 faces two primary challenges. The first concerns technical hurdles with achieving both high CO2 capture rates and low per-ton storage costs. Addressing these issues will require tapping into different parts of the steam reforming process and accessing long-term storage sites—for instance, those in depleted offshore gas fields. The second challenge is public resistance to the development of storage facilities—a subject of heavy debate in most European countries.

Companies are investing in technologies to recycle captured CO2, including for the manufacture of plastics—an effort that would eliminate the need for storage. While such technologies would enhance the business case for carbon capture, the viability and applicability of these technologies remain uncertain.

Blue H2 projects require much more infrastructure than Green H2 projects do, including for CO2 capture, logistics, and final storage. Consequently, Blue H2 facilities must achieve greater scale than Green H2 to be cost efficient. We project that Blue H2 facilities would need to be capable of reducing CO2 emissions by millions of tons annually to enable material economies of scale. At this size, we estimate that total carbon capture and storage costs could be reduced to below 100 €/t, and possibly as low as 50 €/t, depending on the capture rate, the CO2 logistics, and the location of the storage site.

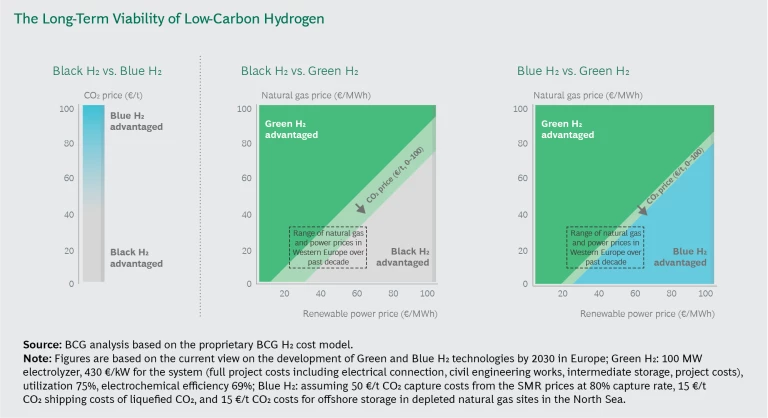

Long-Term Technology Tradeoffs. While every project will have distinct economics, commodity prices will be a key determinant of viability for all technologies. Using our model, and assuming the cost-efficient deployment of Blue and Green H2 by 2030 as outlined above, we can assess how all three types of hydrogen—Black, Blue, and Green—would fare relative to one another in various

The competition between Black and Blue H2 depends on advances in carbon capture and storage as well as the cost of carbon. The competitiveness of Green versus Black depends on advances in electrolysis technology and the cost of three commodities: renewable power, natural gas, and carbon. The competitiveness of Blue versus Green H2 depends on relative technology advances in carbon capture and storage and in electrolysis, as well as the costs of renewable power and gas. (As both Blue and Green are low-carbon, carbon prices have a negligible impact.) When we look at natural gas and power prices in Western Europe over the past ten years, we can see that the large-scale Green H2 operations we outline above would have been competitive with Black H2 under many scenarios.

Our analysis makes clear that there is a viable path to cost-competitive low-carbon hydrogen. Companies making the choice between Blue and Green will need to factor in the outlook for technology advances and commodity prices. And regardless of the technology they choose, they will need an environment characterized by smart, regulatory support.

Building the Right Regulatory Regime

The public sector’s role in hydrogen is just as critical as that of private companies.

Over the past decade, there have been hundreds of low-carbon hydrogen pilots in a variety of applications and industries—most of which have received significant public subsidies. The International Energy Agency estimates that there have been 150 publicly funded hydrogen demo projects in Europe alone and that about $700 million in public research funds flows to hydrogen globally every year. Funding is spread across a plethora of use cases, many of which have limited long-term viability, and where efforts are typically subscale.

Regulators need to direct support toward areas where it can really make a difference rather than opportunistically sprinkling subsidies across the market.

Regulators should now move to the next phase, supporting the scaling up of low-carbon hydrogen. They need to direct support toward areas where it can really make a difference rather than opportunistically sprinkling subsidies across the market. To do this, they should first identify applications where low-carbon hydrogen is the best economic option for reducing carbon emissions. Once those “emission pain points” are identified, governments should incentivize companies to invest in an initial set of projects. That regulatory regime should have three important components:

- CO2 emissions in general, and those stemming from the production of Black H2 in particular, should be priced.

- For areas where there is a viable use for low-carbon hydrogen, government should provide grants to support investments in large-scale facilities. Such support will be a critical—and ultimately cost-efficient—driver of carbon abatement.

- To promote the development of Green H2, governments should create supportive power regulation. This should include the exemption of large electrolyzers that use renewable power from grid fees and levies, similar to the exemptions often enjoyed by energy-intensive industries such as aluminum, paper, and chlorine.

Companies, meanwhile, need to present large-scale low-carbon hydrogen projects that are minimally more expensive than other carbon-free alternatives. Such projects will have the best chance of gaining public support as part of an ambitious climate protection agenda.

How Companies Can Win in Hydrogen

We believe that within the next decade we will see the first large-scale, low-carbon hydrogen applications. To shape these opportunities, and position themselves to gain advantage from them, hydrogen players should integrate several factors into their strategy:

- Insist on long-term viability. Companies looking for quick, single-asset measures to lighten their carbon footprint are better served using tactics such as energy efficiency, electrification, and renewable power sourcing rather than low-carbon hydrogen. Successful players in low-carbon hydrogen will take a long-term view, investing in assets, technologies, and capabilities that present a reasonable business case today but have the potential to offer attractive large-scale investment opportunities over a long time horizon.

- Partner to make the economics work. Few low-carbon hydrogen projects today are likely to yield attractive returns when executed by one party alone. Consequently, companies must partner across the hydrogen and energy value chain. Utilities and technology specialists, for example, can develop low-carbon hydrogen opportunities with industrial companies that own and operate the offtaking infrastructure but lack access to power markets and low-carbon hydrogen know-how. If done right, no single partner will make outsized returns on these projects—but no one will suffer hefty losses.

- Evaluate end-to-end system value. Companies in the low-carbon hydrogen market need to optimize their systems across the value chain—from feedstock to end-use applications. Owners of wind and solar farms, for example, can in some cases link their renewable power assets directly to an electrolyzer, resulting in benefits on both ends: the renewable power company reduces market risk by securing a long-term contract, and the low-carbon hydrogen plant locks in a low-cost, green electricity source.

- Build on your competitive advantages. Scaling up low-carbon hydrogen will not be for everyone. Companies that have competitive advantages in terms of assets and capabilities—and are able to build on those advantages—will prevail. Companies pursuing Blue H2, for example, should ensure that they can leverage a network of underground storage facilities, gas infrastructure, and petrochemical expertise, and are able to offtake the volume. Owning or having access to these assets and capabilities allows faster scaling and helps mitigate technical and commercial risk.

- Engage regulators with openness and honesty. Scaling up and deploying low-carbon hydrogen solutions is no easy feat. It will require the private sector to put skin in the game and societies to support these projects. Companies should initiate a fact-based dialogue with regulators, one that focuses on the importance of achieving sufficient scale and is honest about the challenges ahead. One integrated utility, for example, teamed with steel players in a discussion with a national government to drive carbon abatement in steel over a 20-year period. That dialogue ultimately resulted in government support for projects to use low-carbon hydrogen in steel production—efforts that met government goals of reducing carbon emissions and fostering the long-term competitiveness of the country’s steel sector.

From Hype to Reality

Low-carbon hydrogen represents a massive business opportunity. If countries make good on their promises to limit global warming to 2°C, low-carbon hydrogen could become a trillion-dollar market. And even if just a fraction of this demand materializes, the potential business opportunity is too big for companies, particularly in the energy sector, to watch from the sidelines.

That’s why large industrial companies, equipment players, utilities, and investors must move today, developing a systemic understanding of low-carbon hydrogen technologies—their costs, possible development trajectory, and their competitive position against other technologies in certain target applications. Armed with insight on where low-carbon hydrogen makes economic sense, they can develop the right technology and investment portfolio to direct their resources to the best opportunities with the lowest risk.

Those who understand where and how to leverage the power of low-carbon hydrogen will carve out a position for themselves in a fast-growing market—and in the process will be critical drivers of progress against climate change. It will not be easy, but for the winners it will be worth it.